See Page 20 CITATION: Target Canada Co

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eleven Points Logistics Begins Servicing Target Stores Cornwall's Economy Offers Opportunities 2012 Was a Great Year, and 2013 Is Continuing That Positive Trend

Eleven Points Logistics Begins Servicing Target Stores Cornwall's Economy Offers Opportunities 2012 was a great year, and 2013 is continuing that positive trend Cornwall is a busy place these days. It Activity has been consistent over time the City’s wastewater treatment facility. may come as a surprise to some, but to and across all sectors. While some major Work has been completed at the hospital, those who have been following what is projects have dominated the headlines, and the other two projects are on happening in Eastern Ontario, it is a story small to medium sized investments have schedule for completion by 2016. that began a few years ago and shows also been strong. little sign of abating. Investments by Cornwall has also welcomed new private and public organizations are One key project has been the completion commercial development, with new adding to a level of development activity of the 1.4 million sq.ft. Eleven Points restaurants opening in the heart of the not seen in the region in decades, and Logistics distribution centre that will city and new retail plazas being built in it bodes well for the future. begin servicing Target stores in Eastern multiple areas. Construction activity has Canada. This project required the been equally split between big box retail Let’s take a look at some of the numbers. construction of a new road, which has in complexes and smaller, local entrepre- turn opened up another 200 acres for neurial efforts, and taken as a whole, In 2005, the 10-year rolling average of development in the Cornwall Business activity in this sector has been building permits issued by the City was Park. -

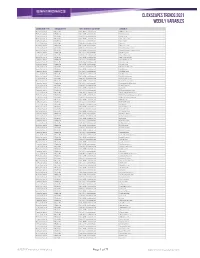

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

Public Accounts of the Province of Ontario for the Year Ended March

PUBLIC ACCOUNTS, 1994-95 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS Hon. Elmer Buchanan, Minister DETAILS OF EXPENDITURE Voted Salaries and Wages ($87,902,805) Temporary Help Services ($1,329,292): Management Board Secretariat, 1,220,010; Accounts under $50,000—109,282. Less: Recoveries from Other Ministries ($196,635): Environment and Energy, 196,635. Employee Benefits ($13,866,524) Payments for Canada Pension Plan, 1 ,594,486; Dental Plan, 95 1 ,332; Employer Health Tax, 1 ,702,083; Group Life Insurance, 170,970; Long Term Income Protection, 1,028,176; Supplementary Health and Hospital Plan, 1,016,690; Unemployment Insurance, 3,017,224; Unfunded Liability— Public Service Pension Fund, 1,024,574. Other Benefits: Attendance Gratuities, 401,716; Death Benefits, 18,660; Early Retirement Incentive, 467,244; Maternity/Parental/Adoption Leave Allowances, 530,045; Severance Pay, 1,494,057; Miscellaneous Benefits, 51,035. Workers' Compensation Board, 315,097. Payments to Other Ministries ($152,141): Accounts under $50,000—152,141. Less: Recoveries from Other Ministries ($69,006): Accounts under $50,000—69,006. Travelling Expenses ($3,859,979) Hon. Elmer Buchanan, 7,002; P. Klopp, 3,765; R. Burak, 9,912; W.R. Allen, 13,155; D.K. Alles, 16,276; P.M. Angus, 23,969; D. Beattie, 12,681; A. Bierworth, 14,510; J.L. Cushing, 12,125; L.L. Davies, 11,521; P. Dick, 16,999; E.J. Dickson, 11,231; R.C. Donais, 10,703; J.R. Drynan, 10,277; R. Dunlop, 10,662; JJ. Gardner, 43,319; C.L. Goubau, 12,096; N. Harris, 12,593; F.R Hayward, 26,910; M. -

Moneygram | Canada Post

Pay for utilities, phone services, cable bills and more at your local post office with MoneyGram! Please consult the list below for all available billers. Payez vos factures de services publics, de services téléphoniques, de câblodistribution et autres factures à votre bureau de poste local avec MoneyGram! Consultez la liste ci-dessous pour tous les émetteurs de factures participants. A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z BILLER NAME/ PROVINCE AVAILABLE SERVICE/ NOM DE L’ÉMETTEUR DE FACTURE SERVICE DISPONIBLE 310-LOAN BC NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT 407 ETR ON NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT A.R.C. ACCOUNTS RECOVERY CORPORATION BC NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT AAA DEBT MANAGERS BC NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT ABERDEEN UTILITY SK NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT ABERNETHY UTILITY SK NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT ACCORD BUSINESS CREDIT ON NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT ACTION COLLECTIONS & RECEIVABLES MANAGEMENT ON NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT AFFINITY CREDIT SOLUTIONS AB NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT AJAX, TOWN OF - TAXES ON NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT ALBERTA BLUE CROSS AB NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT ALBERTA MAINTENANCE ENFORCEMENT PROGRAM AB NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT ALBERTA MOTOR ASSOCIATION - INSURANCE COMPANY AB NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT ALGOMA POWER ON NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT ALIANT ACTIMEDIA NL NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT ALIANT MOBILITY - NS/NB NS NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT ALIANT MOBILITY / NL NS NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT ALIANT MOBILITY/PEI PE NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT ALLIANCEONE ON NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT ALLSTATE INSURANCE ON NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT ALLY CREDIT CANADA ON NEXT DAY/JOUR SUIVANT ALLY CREDIT CANADA LIMITED (AUTO) -

Evidence of the Standing Committee On

43rd PARLIAMENT, 2nd SESSION Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development EVIDENCE NUMBER 032 Monday, May 17, 2021 Chair: Mr. Francis Scarpaleggia 1 Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development Monday, May 17, 2021 ● (1430) [Translation] [English] The Chair (Mr. Francis Scarpaleggia (Lac-Saint-Louis, In December of last year, we published Canada's strengthened Lib.)): I will call the meeting to order. climate plan. This plan is one of the most detailed GHG reduction plans in the world. Welcome to the 32nd meeting of the House of Commons Stand‐ ing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development, for Recognizing the scientific imperative for early and ambitious ac‐ the first meeting of our clause-by-clause study of Bill C-12. tion, we announced a new 2030 target of a 40% to 45% reduction in I think everyone here is experienced with the modus operandi of GHG emissions at the Leaders Summit on Climate in April. committees, especially in virtual space, so I won't go over that. [English] We have with us again today, with great pleasure, Minister Wilkinson. Joining him, from the Department of Finance is Mr. Measures announced in budget 2021, along with ongoing work Samuel Millar, director general, corporate finance, natural re‐ with our American colleagues on issues including transportation sources and environment, economic development and corporate fi‐ and methane, will support that new target. We know more action nance branch. We also have, from the Department of the Environ‐ will be required. This continued ambition is what Canadians ex‐ ment, John Moffet, who was with us as well last week, assistant pect—that we will continue to prioritize climate action, and that we deputy minister, environmental protection branch; and Douglas will work to achieve targets that are aligned with science. -

Dixie Outlet Mall

Dixie Outlet Mall 1250 S Service Rd Property Overview Mississauga, ON L5E 1V4 D'une superficie de 571 000 pieds carrés, le Dixie Outlet Mall est le plus grand centre commercial fermé au Canada dans l'une des régions du Canada qui connaît la croissance la plus rapide. Situé le long de la QEW à Mississauga, le Dixie Outlet Mall abrite plus de 130 magasins d'usine et détaillants à bas prix, notamment Tommy Hilfiger Outlet, Calvin Klein, Guess Factory Store, NIKE Clearance, Levi's Outlet, Famous Footwear, Boathouse Outlet, Winners, Urban. Planet et Laura. Contacts LOCATION Jelena Pukli 416-681-9319 [email protected] LOCATION SPECIALITé Amanda Rakhra 905-278-3494 ext 224 [email protected] GESTIONNAIRE DE Jerry Pollard 905-278-3494 ext 226 [email protected] L'IMMEUBLE DIRECTEUR MARKETING Amanda Rakhra 905-278-3494 ext 224 [email protected] DIRECTEUR DES Eric Puse 905-278-3494 ext 225 [email protected] OPéRATIONS RESPONSABLE DE LA Jordan Hill 905-278-3494 ext 228 [email protected] SéCURITé Dixie Outlet Mall Property Facts TOTAL GLA NUMBER OF FOOD COURT SEATS 426 632 sq ft 448 CRU SQUARE FOOTAGE CRU SALES PER SQ FT 218 840 sq ft $360.00 ANCHORS/MAJORS YEAR BUILT (OVER 20,000 SQ FT) 1956 Laura, Urban Planet, Nike, YEAR LAST RENOVATED Winners 2003 NUMBER OF STORES HOURS OF OPERATION 141 lundi a vendredi 10:00am to 9:00pm samedi 9:30am - 6:00pm dimanche 11:00am - 6:00pm NUMBER OF PARKING SPACES 2500 BUILDING CERTIFICATIONS & AWARDS BOMA Best Silver Dixie Outlet Mall Trade Area Demographics Summary Total Population 5 km: 211,037 10 km: 691,109 15 km: 1,532,695 Average Household Income 5 km: $100,624 10 km: 120,254 15 km: 112,749 Basement Dixie Outlet Mall Dixie Outlet Mall SPRINKLER UP ROOM UP UP MECHANICAL ROOM ELECTRICAL ROOM UP MECHANICAL ROOM UP UP UP UP UP Fantastic Flea Market 50,998 sf B05. -

BCE Inc. 2015 Corporate Responsibility Report

MBLP16-006 • BELL • ANNONCE • LET'S TALK • INFO: MJ/KIM PUBLICATION: MÉTRO TORONTO / CALGARY / EDMONTON / VANCOUVER (WRAP C2) • VERSION: ANGLAISE • FORMAT: 10’’ X 11,5’’ • COULEUR: CMYK • LIVRAISON: 18 JANVIER • PARUTION: 27 JANVIER Today put a little into somebody’s day Today is Bell Let’s Talk Day. For every text, mobile or long distance call made by a subscriber*, and tweet using #BellLetsTalk, Bell will donate 5¢ more to mental health initiatives across the country. #BellLetsTalk *RegularBCE long distance and text message charges Inc. apply. bell.ca/letstalk 2015 Corporate MBLP16-006 Let'sTalk_Metro_ENG_WRAP_C2.indd 1 2016-01-08 09:54 Responsibility Report TOC > Alexander Graham Bell was looking for a new way for people to connect across distances. Little did he know his invention would change the world. What Bell started has transformed the way people interact with each other and the information they need to enrich their lives. As the Canadian steward of Bell’s legacy, BCE is committed to deliver those benefits in the most responsible manner possible. TOC < 2 > BCE at a glance BCE at a glance TEAM MEMBERS Bell named one of 82% of employees are proud to Bell increased investment Bell made a voluntary Reduced lost-time accidents Canada’s Top Employers work for Bell in training by 8% per employee $250 million contribution to by 41% for construction teams solidify pension plan building new networks 82% 8% $250M 41% CUSTOMERS Highly efficient self-serve Bell became #1 TV provider Provided 2-hour appointment Extended retail network Broadband fibre and wireless options used 160 million times in Canada with 2.7 million windows to 600,000 Bell Fibe leadership, adding Glentel networks – including largest by customers subscribers customers outlets to bring total to more Gigabit Fibe and 4G LTE than 2,500 across the country wireless – earn #1 ranking in Canada 160M 2.7M 600,000 2,500 No. -

Q2 2015 Shareholder Report

BCE Inc. 2015 Second Quarter Shareholder Report Results speak volumes. Q2 AUGUST 5, 2015 Table of contents MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS 1 1 OVERVIEW 2 1.1 Financial highlights 2 1.2 Key corporate and business developments 3 1.3 Assumptions 4 2 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL ANALYSIS 5 2.1 BCE consolidated income statements 5 2.2 Customer connections 5 2.3 Operating revenues 6 2.4 Operating costs 7 2.5 Adjusted EBITDA 8 2.6 Severance, acquisition and other costs 9 2.7 Depreciation and amortization 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE 2.8 Finance costs 10 2.9 Other income (expense) 10 2.10 Income taxes 10 2.11 Net earnings and EPS 11 3 BUSINESS SEGMENT ANALYSIS 12 3.1 Bell Wireless 12 3.2 Bell Wireline 17 3.3 Bell Media 22 4 FINANCIAL AND CAPITAL MANAGEMENT 25 4.1 Net debt 25 4.2 Outstanding share data 25 4.3 Cash flows 26 4.4 Post-employment benefit plans 28 4.5 Financial risk management 28 4.6 Credit ratings 30 4.7 Liquidity 30 5 QUARTERLY FINANCIAL INFORMATION 31 6 REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT 32 7 BUSINESS RISKS 34 8 ACCOUNTING POLICIES, FINANCIAL MEASURES AND CONTROLS 36 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 39 NOTES TO CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 44 Note 1 Corporate information 44 Note 2 Basis of presentation and significant accounting policies 44 Note 3 Segmented information 44 Note 4 Operating costs 47 Note 5 Severance, acquisition and other costs 47 Note 6 Other income (expense) 48 Note 7 Acquisition of Glentel 48 Note 8 Earnings per share 48 Note 9 Acquisition of spectrum licences 49 Note 10 Debt 49 Note 11 Post-employment benefit plans 49 Note 12 Financial assets and liabilities 50 Note 13 Share-based payments 51 MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION MD&A AND ANALYSIS In this management’s discussion and analysis of financial condition and results of operations (MD&A), we, us, our, BCE and the company mean, as the context may require, either BCE Inc. -

Annual Information Form

ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM Year Ended May 7, 2016 July 20, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS ..................................................................................................... 1 CORPORATE STRUCTURE .................................................................................................................... 3 Name and Incorporation ................................................................................................................ 3 Intercorporate Relationships ......................................................................................................... 3 DESCRIPTION OF THE BUSINESS ........................................................................................................ 4 Food Retailing ............................................................................................................................... 4 Investments and Other Operations ............................................................................................... 7 Competition ................................................................................................................................... 7 Other Information .......................................................................................................................... 8 GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BUSINESS ................................................................................... 9 Focus on Food Retailing .............................................................................................................. -

The Royal Gazette Index 2016

The Royal Gazette Gazette royale Fredericton Fredericton New Brunswick Nouveau-Brunswick ISSN 0703-8623 Index 2016 Volume 174 Table of Contents / Table des matières Page Proclamations . 2 Orders in Council / Décrets en conseil . 2 Legislative Assembly / Assemblée législative. 6 Elections NB / Élections Nouveau-Brunswick . 6 Departmental Notices / Avis ministériels. 6 Financial and Consumer Services Commission / Commission des services financiers et des services aux consommateurs . 9 NB Energy and Utilities Board / Commission de l’énergie et des services publics du N.-B. 10 Notices Under Various Acts and General Notices / Avis en vertu de diverses lois et avis divers . 10 Sheriff’s Sales / Ventes par exécution forcée. 11 Notices of Sale / Avis de vente . 11 Regulations / Règlements . 12 Corporate Registry Notices / Avis relatifs au registre corporatif . 13 Business Corporations Act / Loi sur les corporations commerciales . 13 Companies Act / Loi sur les compagnies . 54 Partnerships and Business Names Registration Act / Loi sur l’enregistrement des sociétés en nom collectif et des appellations commerciales . 56 Limited Partnership Act / Loi sur les sociétés en commandite . 89 2016 Index Proclamations Lagacé-Melanson, Micheline—OIC/DC 2016-243—p. 1295 (October 26 octobre) Acts / Lois Saulnier, Daniel—OIC/DC 2016-243—p. 1295 (October 26 octobre) Therrien, Michel—OIC/DC 2016-243—p. 1295 (October 26 octobre) Credit Unions Act, An Act to Amend the / Caisses populaires, Loi modifiant la Loi sur les—OIC/DC 2016-113—p. 837 (July 13 juillet) College of Physicians and Surgeons of New Brunswick / Collège des médecins Energy and Utilities Board Act / Commission de l’énergie et des services et chirurgiens du Nouveau-Brunswick publics, Loi sur la—OIC/DC 2016-48—p. -

2015 BCE Notice of Special Meeting Management Information Circular

NOTICE OF SPECIAL MEETING OF SECURITYHOLDERS AND MANAGEMENT INFORMATION CIRCULAR Our special meeting of securityholders will be held at 9:00 a.m. (Vancouver time), on Monday January 12, 2015, at the Coal Harbour Room, Pan Pacific Hotel, 999 Canada Place, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6C 3B5. Securityholders of GLENTEL Inc. have the right to vote their securities, either by proxy or in person, at the meeting. Your vote is important. This document tells you who can vote, what securityholders will be voting on and how securityholders can exercise the right to vote their securities. Please read it carefully. GLENTEL INC. December 11, 2014 (This page intentionally left blank) LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD, PRESIDENT AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER December 11, 2014 Dear fellow securityholder: You are invited to attend a special meeting of securityholders of GLENTEL Inc. (“GLENTEL”). The meeting will be held on January 12, 2015, at 9:00 a.m. (Vancouver time), at the Coal Harbour Room, Pan Pacific Hotel, 999 Canada Place, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, V6C 3B5. At the special meeting, among other things, you will be asked to consider and, if thought appropriate, to pass, with or without variation, a special resolution approving a statutory arrangement pursuant to section 192 of the Canada Business Corporations Act (the “Arrangement”) involving, among other things, the acquisition by BCE Inc. (“BCE”) of all of the outstanding common shares of GLENTEL (the “Shares”). Under the Arrangement, holders of Shares will be entitled to receive, at the election of each holder, cash of $26.50 per Share, or 0.4974 common shares of BCE (“BCE Common Shares”), per Share, as described in more detail in the accompanying information circular. -

Telecommunications Provider Locator

Telecommunications Provider Locator Industry Analysis & Technology Division Wireline Competition Bureau January 2010 This report is available for reference in the FCC’s Information Center at 445 12th Street, S.W., Courtyard Level. Copies may be purchased by contacting Best Copy and Printing, Inc., Portals II, 445 12th Street S.W., Room CY-B402, Washington, D.C. 20554, telephone 800-378-3160, facsimile 202-488-5563, or via e-mail at [email protected]. This report can be downloaded and interactively searched on the Wireline Competition Bureau Statistical Reports Internet site located at www.fcc.gov/wcb/iatd/locator.html. Telecommunications Provider Locator This report lists the contact information, primary telecommunications business and service(s) offered by 6,493 telecommunications providers. The last report was released March 13, 2009.1 The information in this report is drawn from providers’ Telecommunications Reporting Worksheets (FCC Form 499-A). It can be used by customers to identify and locate telecommunications providers, by telecommunications providers to identify and locate others in the industry, and by equipment vendors to identify potential customers. Virtually all providers of telecommunications must file FCC Form 499-A each year.2 These forms are not filed with the FCC but rather with the Universal Service Administrative Company (USAC), which serves as the data collection agent. The pool of filers contained in this edition consists of companies that operated and collected revenue during 2007, as well as new companies that file the form to fulfill the Commission’s registration requirement.3 Information from filings received by USAC after October 13, 2008, and from filings that were incomplete has been excluded from this report.