ASC Bulletin 76 2014 Field Clearing: Stone Removal and Disposal Practices in Agriculture & Farming James E. Gage with a Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logan Citys How to Compost in Color.Pub

How to compost at home 1) Designate a place in your yard to start a compost pile . Typically you will want to find an area that is semi-shady, dry, and well-drained. You will want to make sure your pile is located close to a water source in order to add moisture as needed to your pile. If you do not have a location next to a water source, you can always add materials that are high in moisture such as grass clippings. If you are adding a lot of kitchen scraps and grass clippings, you most likely will not need to add moisture by the means of a garden hose . 2) Figure out what type of bin, if any, you would like to use. There are many different methods to compost when it comes to choosing a bin. You may accumulate the compost material in a loose pile to choos- ing an elaborate rotational bin system. Old wood pallets work great if you opt to build one yourself. There are also places to purchase a compost bin. 3) Start adding your yard waste. In the world of composting, gardeners talk about compost material in terms of “Greens” and “Browns.” Green material is high in nitrogen and brown materials are high in carbon. A good way to tell the difference between the two is moisture content. Green materials are typically high in moisture such as grass clippings whereas Brown materials are typically dry such as leaves. Green materials is what helps speed up the decomposition process. A 25-30:1 ratio of C:N is ideal for composting. -

Final-Portafolio-2017.Pdf

ó Pacific Curbing is the leading company for Pinellas & Hillsborough area decorative concrete landscape curbing. Our decorative, stamped curbing is on the cutting edge of landscape design. 11/11/2016 2 ó Concrete curbing is a professionally installed, permanent, attractive concrete border edging that provides great additions and solutions to any landscape and serves as a weed and grass barrier by outlining flowerbeds. Pacific Curbing decorative concrete curbing can be installed around trees, flowerbeds, sidewalks and just about anywhere you like. 11/11/2016 3 ó Concrete curbing can enhance your landscape, it is the half of price of bricks and is a permanent solution, increase curb appeal, decrease the time spent trimming around landscape beds and increase your property value. 11/11/2016 4 ó Rollers are a soft textures impresions on the concrete curbing for the angle mold 6x4. ó You can choose a natural looking like stone or you can choose something symetrical. ó Price per foot $5.75 ó You can choose any color up 3lb ó Project is seal with the UV Sealer. ó PSI 3600 Ashlar Basketweave Brick Bone Cobblestone Flagstone H Brick Herringbone Offset bond Old stone Pebblestone Random Riverstone Running bond L Running bond Slate Spanish Texture Treebark Wood RAMDOM ROLLER RUNNING BOND ROLLER SLATE ROLLER FLAGSTONE ROLLER SPANISH TEXTURE SINGLE BRICK ó Stamps are deep impresions on the concrete curbing for the angle mold 6x4. ó They come on a symetrical designs. ó Price per foot $6 ó You can choose any color up 3lb ó Project is seal with the UV Sealer. -

Landscape Tools

Know your Landscape Tools Long handled Round Point Shovel A very versatile gardening tool, blade is slightly cured for scooping round end has a point for digging. D Handled Round Point Shovel A versatile gardening tool, blade is slightly cured for scooping round end has a point for digging. Short D handle makes this an excellent choice where digging leverage is needed. Good for confined spaces. Square Shovel Used for scraping stubborn material off driveways and other hard surfaces. Good for moving small gravel, sand, and loose topsoil. Not a digging tool. Hard Rake Garden Rake This bow rake is a multi-purpose tool Good for loosening or breaking up compacted soil, spreading mulch or other material evenly and leveling areas before planting. It can also be used to collect hay, grass or other garden debris. Leaf rake Tines can be metal or plastic. It's ideal for fall leaf removal, thatching and removing lawn clippings or other garden debris. Tines have a spring to them, each moves individually. Scoop Shovel Grain Shovel Has a wide aluminum or plastic blade that is attached to a short hardwood handle with "D" top. This shovel has been designed to offer a lighter tool that does not damage the grain. Is a giant dust pan for landscapers. Edging spade Used in digging and removing earth. It is suited for garden trench work and transplanting shrubs. Generally a 28-inch ash handle with D-grip and open-back blade allows the user to dig effectively. Tends to be heavy but great for bed edging. -

How to Install Dry-Laid Flagstone Complete Step by Step “How-To

How To Install Dry-Laid Flagstone Patio or Walkway Complete step by step “How-to” guide for building a dry-laid patio or walkway. Copyright © 2012 Stone Plus, Inc. How To Build A Dry Laid Flagstone Patio or Walkway As there is no single “right way” to install dry laid flagstone, we have found the following to be a solid tech- nique. Choosing Your Stone Stone for walkways and patios come in many colors, shapes, textures and sizes. When selecting the stone for your pavement, keep in mind the concept, or idea, that form fits function. When laying a dry laid patio, one should use a thicker stone that is 3/4” to 2-1/2” thick. Any thinner stone will be subject to cracking. Thinner stones are used when installing stone over an existing concrete slab. Pictured to the right is the Arizona Buff Patio flagstone. As you can see, this stone has irregular edges and may need fitting in order to get the look you desire. Pictured above: Buff Patio When installing a primary walkway or patio that has high traffic or is an entertainment area, thought should be given to selecting larger and flatter flagstone. Women in high heels, or the leg of a table and chair, find larger, flatter stones more compatible with their needs. When installing a “garden path or retreat”, the use of smaller, more irregular stone is appropriate. So when choosing a flagstone for your pavement, one should consider the purpose of the pavement. Consider the texture and size of the stone in relation to its intended pur- pose. -

The Development of Hay Harvesting Machinery in the High Hollows Of

THE DEVELOPMENT OF HAY HARVESTING MACHINERY IN THE HIGH HALLOWS OF ROCKBRIDGE COUNTY Daniel Strake Parsley Dr. John McDaniel Anthropology 377 May 27, 1983 The development of techniques and machinery used in the harvesting of hay has been most significant in the last 100 years. Due to the rapid yet recent development it is possible to find individuals who have lived through the changes of tools and equipment needed to cut, rake, and either stack or bale hay. Each area of the country has had a different development, therefore I have concentrated my efforts to the development of hay harvesting machinery in High Hallows area in Rockbridge County. My efforts have been greatly a result of the aid of two very knowledgable local farmers: Clarence Wilhem of Denmark, Virginia and c. W. Spradlin of Stuartsville, Virginia which is just north of Roanoke. The development has gone through three distinct yet overlapping stages: (1) manual, hand operated tools, (2) horse-drawn equipment, and (3) modern, tractor operated machines. The history of hay harvesting machinery is sitting at our back doors. As shown in the many photographs of actual machinery in this area, many of the old machines have been left out to rust away. By inquiring to these two kind men, I am able to trace the entire history from the manual, hand tools to the latest modern machines of today. Ever since man began domesticating plants and animals, the need to cut grass and crops existed. The sickle has been proven to be one of the older tools known. This large semi-circular blade is still used today as the main tool in the mowing process -2- of hay and crops in some areas of the world. -

Hardscapes Aren't Really So Hard

Hardscapes Aren’t Really So Hard Designing with old and new hard materials to create beautiful, functional and lasting patios, walks and walls HARDSCAPING BASICS: Flatwork and Walls have similar components • Compacted sub-base. Proctor Density • Footing—concrete v. compacted • Setting Bed—mortar or sand • Veneer materials • Cap for wall, edge course for flatwork • Drainage—1/8” per foot min, french drain and weep holes for walls Off white board Hard Materials • Natural: Fieldstone, flagstone, aggregate, river slicks, etc • Manmade: Brick, concrete, tile, etc • Mortared vs dry laid Thermal bluestone flagstone treads, fieldstone riser and wall veneer Fieldstone used as wall boulders and fireplace veneer, flagstone patio dry laid with crushed slate joints Intergral color concrete patio Poured in place intergral color concrete steps, walls and patio Brick paver patio on compacted crusher run base and mortared brick veneer on grill station. Blue stone cap and adjacent patio set with mortar DESIGNING WITH HARDSCAPES • “Blending” vs “Matching” • Everything is a room or hallway • Outdoor rooms: floors, walls, ceilings • Creativity and beauty by using a few materials in new ways A range of colors in the pavers makes it easier to blend with surrounding materials Outdoor rooms have floors, walls and ceilings Use changes in material to differentiate outdoor rooms Everything is a “room” or “hallway” Avoid the ‘concrete doughnut’ pool deck by designing rooms as dominate hardscape connected by walkways PA bluestone 4 ways: You don’t have to change materials -

How to Build a Dry Stone Wall an Instructional Guide for Beginners

Do- It-Yourself: How to Build a Dry Stone Wall An instructional guide for beginners © Copyright Stephen Burton and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons License. By: Stephen T. Kane Table of Contents: INTRODUCTION………………………………………………….3 TOOLS, EQUIPMENT, AND SUPPLIES………………………4 GROUNDWORK…………….…………………………………….7 FOUNDATION…………………………………………………….8 COURSING.…………………………………………………………9 COPING.……………………………………………………………10 GLOSSARY………………………………………………………..11 Introduction: Whether for pure aesthetics or practical functionality, dry stone walls employ the craft of carefully stacking and interlocking stones without the use of mortar to form earthen boundaries, residential foundations, agricultural terraces, and rudimentary fences. If properly constructed, these creations will stand unabated for countless years, requiring only minimal maintenance and repairs. The ability to harness the land and shape it in a way that meets one’s needs through stone walling allows endless possibility and enjoyment after fundamental steps and basic techniques are learned. How to Build a Dry Stone Wall provides a comprehensive reference for beginners looking to start and finish a wall project the correct way. A list of essential resources and tools, a step-by-step guide, and illustrations depicting proper construction will allow readers to approach projects with a confidence and a precision that facilitates the creation of beautiful stonework. If any terminology poses an issue, simply reference the glossary provided in the back of the booklet. NOTE: Depending on property laws and building codes, many areas do not permit stone walls. Check with respective sources to determine if all residential rules and regulations will abide stonework. Also, before building anything on a property line, always consult your neighbor(s) and get their written consent. -

City of Roswell, Georgia Classification Specification

Code: R02 CITY OF ROSWELL, GEORGIA FLSA: N WC: 9102 CLASSIFICATION SPECIFICATION EEO: 8 CLASSIFICATION TITLE: PART TIME PARKS CREW WORKER II Applications are only accepted on-line at www.roswellgov.com/employment PURPOSE OF CLASSIFICATION The purpose of this classification is to perform manual work, at a moderate to high level of skill, as part of a crew engaged in maintenance, turf, construction, and upkeep of public parks, grounds, facilities and Historical Assets. Work is physical in nature and under the direct supervision of a Coordinator, Crew Supervisor or Crew Leader. ESSENTIAL FUNCTIONS The following duties are normal for this position. The omission of specific statements of the duties does not exclude them from the classification if the work is similar, related, or a logical assignment for this classification. Other duties may be required and assigned. Performs manual work within city parks, which may involve landscape and grounds maintenance, general parks maintenance, facilities maintenance, or construction projects; assists equipment operators, skilled-trade employees, or other workers as needed. Performs various tasks involving grounds maintenance or landscaping projects: mows grass; trims and edges along roadways, landscaped areas, driveways, sidewalks, and fence lines; plants and maintains trees, shrubs, and flowers; weeds flower beds; cuts down trees; prunes tree limbs, hedges, and shrubs; picks up and disposes of tree limbs, brush, and other materials from public areas; spreads seed, mulch, and other grounds materials; tills or aerates dirt/soil; moves dirt and grades land; cuts, lays, or installs sod; applies fertilizer and herbicide; rakes ground materials; blows leaves/debris from walkways or grounds; picks up and disposes of debris/litter from public areas; empties trash containers; digs holes/trenches and shovels materials. -

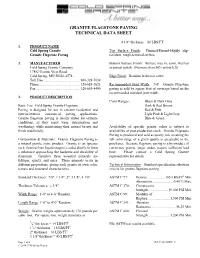

Granite Flagstone Paving Technical Data Sheet

GRANITE FLAGSTONE PAVING TECHNICAL DATA SHEET 4 1/8" thickness = 60 LBS/FT2 1. PRODUCT NAME Cold Spring Granite Top Surface Finish: Thermal/Flamed-Highly slip- Granite Flagstone Paving resistant, rough-textured surface. 2. MANUFACTURER Bottom Surface Finish: Surface may be sawn, thermal Cold Spring Granite Company or partial polish. (No more than 50% polish left) 17482 Granite West Road Cold Spring, MN 56320-4578 Edge Finish: Random broken or sawn Toll Free .......................................... 800-328-7038 Phone ............................................... 320-685-3621 Recommended Joint Width: 3/4". Granite Flagstone Fax ................................................... 320-685-8490 paving is sold by square foot of coverage based on the recommended standard joint width. 3. PRODUCT DESCRIPTION Color Ranges: Black & Dark Gray Basic Use: Cold Spring Granite Flagstone Dark & Red Brown Paving is designed for use in exterior residential and Red & Pink interior/exterior commercial paving applications. Light Pink & Light Gray Granite flagstone paving is ideally suited for extreme Blue & Green conditions, as they resist wear, deterioration and weathering, while maintaining their natural beauty and Availability of specific granite colors is subject to finish indefinitely. availability of post-production stock. Granite Flagstone Paving is produced and sold as quarry run, meaning the Composition & Materials: Granite Flagstone Paving is full color range of a given quarry is acceptable to the a natural granite stone product. Granite is an igneous purchaser. Because flagstone paving is a by-product of rock, formed from liquid magma, cooled slowly to form cut-to-size granite, larger orders require sufficient lead a substance approaching the hardness and durability of time. Please contact a Cold Spring Granite diamonds. -

Rental Prices

FISHING & BOATING WEEKLY CONTACT US Items Daily Rate The fee is ve times the daily rate and covers a full seven day HOURS: 23D FORCE SUPPORT SQUADRON Boat (12 ft/14 ft Jon) $8 period. Holidays and days of closure included. Mon - Fri: 8 am - 4 pm MOODY AIR FORCE BASE, GA Boat Paddle (Pair) $2 CLEANING FEE Sat: 8 am - 12 pm Boat Trailer $15 A cleaning deposit is required when renting any tent, camper, *Hours are subject to change Canoe $14 or canopy. This deposit will be refunded based on the Canoe Trailer (2-inch) $15 condition of the equipment when it’s returned. The amount of ADDRESS: Canoe & Trailer $25 the deposit will be a one-day rental fee. 4251 George St, Bldg 840 EQUIPMENT RENTAL Carrier (Boat) $2.50 LATE FEE Moody AFB, GA 31699 Cushions (Boat) $2 Equipment overdue by one (1) hour or more may be assessed a FEES & CHARGES Fish Cooker (Propane) $5 late fee of twice the daily rate plus $1 per line item. PHONE: WWW.MOODYFSS.COM Kayak (1-person) $12 (229) 257-2989 DSN 460-3297 Kayak (2-person) $14 BUDGET TRUCK RENTAL Budget Truck Rental: Life Vest $2 • Great one-way and local rates (229) 247-2894 Rod & Reel (Fresh water) $2 • On-base location Trolling Motor/Battery $10 • Full line of moving supplies WEBSITE: www.moodyfss.com facebook.com/moodyfss JON BOAT PACKAGES ENTERPRISE RENT-A-CAR $45 per day • On-base location 12 or 14 foot Jon Boat • Great leisure travel or TDY rates 6-horsepower or 8-horsepower gas motor Trailer (2-inch ball) RV STORAGE LOTS 2 Paddles, 2 Cushions and 2 Life Vests • Secure, on-base locations to store your recreation vehicle • 20 ft. -

The Elegance of Simplicity. the Elegance of Simplicity

The elegance of simplicity. g{x ÑÉãxÜ Éy |ÇzxÇ|Éâá wxá|zÇA The durability of concrete. Continuous concrete borders to enhance any landscape design. Other Services Sealant Re-spraying: The Cement Shop Curbing Company can return annually by appointment to re-spray your curbing with a powerful sealant designed to protect its surface and boost glossiness. Continuous Walkways: Ask us about beautifying your property with a continuous-pour concrete pathway. The Cement Shop Curbing Company can create permanent and customizable sidewalks in many unique styles The elegance of simplicity. without the use of concrete forms. Most importantly, the solid pour g{x ÑÉãxÜ Éy |ÇzxÇ|Éâá wxá|zÇA combats the effects of shifting and Your property is your showpiece; The durability of concrete. prevents bothersome weed and a reflection of your distinctive style and moss penetration. a shining example of pride of owner- New Bed Preparation: Looking to ship. Enhance the natural beauty and unique features of your landscape, or add a flower bed to your prop- accent an idyllic outdoor living space erty? The Cement Shop Curbing with continuous concrete curbing from Company’s specialized sod-cutting The Cement Shop Curbing Company. equipment can eliminate for you the hassle of creating new beds manually. Our precision sod- cutter can quickly and gently remove re-usable strips of sod, enabling you to add a whole new 7 Frigate Bay bed to your property without Winnipeg, MB R3X 2E9 having to dig. T: 204.295.4768 [email protected] www.cementshop.ca Contact us today for a professional, no-obligation consultation. -

Hot & Fast Compost Recipe

www.urban-nature.org www.watersmart.cc Hot & Fast Compost Recipe Hot and Fast Composting is building and actively mixing a pile to produce disease-killing temperatures and can yield finished compost within a month. A minimum “batch” is enough to fill a plastic bin or build a pile at least 3 feet high and 3 feet in diameter. This practice destroys most plant diseases, weeds, and weed seeds. Ingredients: Three to 4 or more wheelbarrows of “green” yard materials – such as grass clippings and garden debris Three to 4 or more wheelbarrows of “brown” materials –such as leaves, dry weeds, brush, and woody prunings. Vegetables and fruit scraps and coffee grounds (as available) Water Tools: Pitchfork Square-point shovel or machete (optional) Rotary lawnmower or chipper-shredder (when composting woody material or dry leaves) Water hose with spray head Compost bin (optional) Tarp, burlap, or black plastic for covering the pile and/or mixing materials (optional) Compost thermometer (optional) Directions: 1. Pick a 4-foot by 8-foot area where water does not puddle when it rains, preferably a shaded spot. 2. Chop up the gathered stalks and garden plants with shovel or machete. Chip or shred woody trimmings. 3. Cover half of the 4-foot by 8-foot area with a 6-inch layer of “brown” materials. 4. Add a 3-inch layer of fresh “green” materials, and add a dash of soil or finished compost. 5. Mix this layer lightly into the layer below it with a hoe or hand cultivator. 6. Top with a 3-inch layer of “brown” materials and add water until it is moist.