PALEOCLIMATOLOGY Reconstructing Climates of the Quaternary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meteorology Climate

Meteorology: Climate • Climate is the third topic in the B-Division Science Olympiad Meteorology Event. • Topics rotate annually so a middle school participant may receive a comprehensive course of instruction in meteorology during this three-year cycle. • Sequence: 1. Climate (2006) 2. Everyday Weather (2007) 3. Severe Storms (2008) Weather versus Climate Weather occurs in the troposphere from day to day and week to week and even year to year. It is the state of the atmosphere at a particular location and moment in time. http://weathereye.kgan.com/cadet/cl imate/climate_vs.html http://apollo.lsc.vsc.edu/classes/me t130/notes/chapter1/wea_clim.html Weather versus Climate Climate is the sum of weather trends over long periods of time (centuries or even thousands of years). http://calspace.ucsd.edu/virtualmuseum/ climatechange1/07_1.shtml Weather versus Climate The nature of weather and climate are determined by many of the same elements. The most important of these are: 1. Temperature. Daily extremes in temperature and average annual temperatures determine weather over the short term; temperature tendencies determine climate over the long term. 2. Precipitation: including type (snow, rain, ground fog, etc.) and amount 3. Global circulation patterns: both oceanic and atmospheric 4. Continentiality: presence or absence of large land masses 5. Astronomical factors: including precession, axial tilt, eccen- tricity of Earth’s orbit, and variable solar output 6. Human impact: including green house gas emissions, ozone layer degradation, and deforestation http://www.ecn.ac.uk/Education/factors_affecting_climate.htm http://www.necci.sr.unh.edu/necci-report/NERAch3.pdf http://www.bbm.me.uk/portsdown/PH_731_Milank.htm Natural Climatic Variability Natural climatic variability refers to naturally occurring factors that affect global temperatures. -

Climate Change and Human Health: Risks and Responses

Climate change and human health RISKS AND RESPONSES Editors A.J. McMichael The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia D.H. Campbell-Lendrum London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom C.F. Corvalán World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland K.L. Ebi World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, European Centre for Environment and Health, Rome, Italy A.K. Githeko Kenya Medical Research Institute, Kisumu, Kenya J.D. Scheraga US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, USA A. Woodward University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION GENEVA 2003 WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Climate change and human health : risks and responses / editors : A. J. McMichael . [et al.] 1.Climate 2.Greenhouse effect 3.Natural disasters 4.Disease transmission 5.Ultraviolet rays—adverse effects 6.Risk assessment I.McMichael, Anthony J. ISBN 92 4 156248 X (NLM classification: WA 30) ©World Health Organization 2003 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from Marketing and Dis- semination, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications—whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution—should be addressed to Publications, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

(2016), Volume 4, Issue 2, 77-90

ISSN 2320-5407 International Journal of Advanced Research (2016), Volume 4, Issue 2, 77-90 Journal homepage: http://www.journalijar.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVANCED RESEARCH RESEARCH ARTICLE LICHENOMETRIC DATING CURVE AS APPLIED TO GLACIER RETREAT STUDIES IN THE HIMALAYAS. Gaurav K. Mishra, Santosh Joshi and Dalip K. Upreti. Lichenology Laboratory, CSIR-National Botanical Research Institute, Rana Pratap Marg, Lucknow- 226001. Manuscript Info Abstract Manuscript History: The study critically favours the importance of lichens in estimating palaeoclimatic events and its use in depicting the future discretion regarding Received: 14 December 2015 Final Accepted: 19 January 2016 glacier retreat. Besides the various lichenometric studies carried out in Indian Published Online: February 2016 Himalayan region, the world-wide classical work of different glaciologist and geologist on different applications of lichenometry is also well focused. Key words: The study also highlights the benefits, restrains, and drawbacks associated Lichens, lichenometry,glacier with the lichenometry. Being a globally accepted biological technique retreat,India. particular emphasis is given on the need of innovative approach in implementation of lichenometry in Indian Himalayan region. *Corresponding Author Gaurav K. Mishra. Copy Right, IJAR, 2016,. All rights reserved. Introduction:- Lichens are slow growing organisms and take several years to get established in nature. Lichens are a unique group of plants, comprising of two micro-organisms, fungus (mycobiont), an organism capable of producing food via photosynthesis and alga (photobiont). These photobionts are predominantly members of the chlorophyta (green algae) or cynophyta (blue-green algae or cynobacteria). The peculiar nature of lichens enables them to colonize variety of substrate like rock, boulders, bark, soil, leaf and man-made buildings. -

Aristotle University of Thessaloniki School of Geology Department of Meteorology and Climatology

1 ARISTOTLE UNIVERSITY OF THESSALONIKI SCHOOL OF GEOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF METEOROLOGY AND CLIMATOLOGY School of Geology 541 24 – Thessaloniki Greece Tel: 2310-998240 Fax:2310995392 e-mail: [email protected] 25 August 2020 Dear Editor We have submitted our revised manuscript with title “Fast responses on pre- industrial climate from present-day aerosols in a CMIP6 multi-model study” for potential publication in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. We considered all the comments of the reviewers and there is a detailed response on their comments point by point (see below). I would like to mention that after uncovering an error in the set- up of the atmosphere-only configuration of UKESM1, the piClim simulations of UKESM1-0-LL were redone and uploaded on ESGF (O'Connor, 2019a,b). Hence all ensemble calculations and Figures were redone using the new UKESM1-0-LL simulations. Furthermore, a new co-author (Konstantinos Tsigaridis), who has contributed in the simulations of GISS-E2-1-G used in this work, was added in the manuscript. Yours sincerely Prodromos Zanis Professor 2 Reply to Reviewer #1 We would like to thank Reviewer #1 for the constructive and helpful comments. Reviewer’s contribution is recognized in the acknowledgments of the revised manuscript. It follows our response point by point. 1) The Reviewer notes: “Section 1: Fast response vs. slow response discussion. I understand the use of these concepts, especially in view of intercomparing models. Imagine you have to talk to a wider audience interested in the “effective response” of climate to aerosol forcing in a naturally coupled climate system. -

Conversion of GISP2-Based Sediment Core Age Models to the GICC05 Extended Chronology

Quaternary Geochronology 20 (2014) 1e7 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Geochronology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quageo Short communication Conversion of GISP2-based sediment core age models to the GICC05 extended chronology Stephen P. Obrochta a, *, Yusuke Yokoyama a, Jan Morén b, Thomas J. Crowley c a University of Tokyo Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, 227-8564, Japan b Neural Computation Unit, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology, 904-0495, Japan c Braeheads Institute, Maryfield, Braeheads, East Linton, East Lothian, Scotland EH40 3DH, UK article info abstract Article history: Marine and lacustrine sediment-based paleoclimate records are often not comparable within the early to Received 14 March 2013 middle portion of the last glacial cycle. This is due in part to significant revisions over the past 15 years to Received in revised form the Greenland ice core chronologies commonly used to assign ages outside of the range of radiocarbon 29 August 2013 dating. Therefore, creation of a compatible chronology is required prior to analysis of the spatial and Accepted 1 September 2013 temporal nature of climate variability at multiple locations. Here we present an automated mathematical Available online 19 September 2013 function that updates GISP2-based chronologies to the newer, NGRIP GICC05 age scale between 8.24 and 103.74 ka b2k. The script uses, to the extent currently available, climate-independent volcanic syn- Keywords: Chronology chronization of these two ice cores, supplemented by oxygen isotope alignment. The modular design of Ice core the script allows substitution for a more comprehensive volcanic matching, once it becomes available. Sediment core Usage of this function highlights on the GICC05 chronology, for the first time for the entire last glaciation, GICC05 the proposed global climate relationships during the series of large and rapid millennial stadial- interstadial events. -

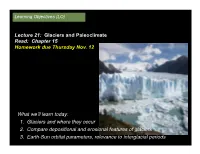

Lecture 21: Glaciers and Paleoclimate Read: Chapter 15 Homework Due Thursday Nov

Learning Objectives (LO) Lecture 21: Glaciers and Paleoclimate Read: Chapter 15 Homework due Thursday Nov. 12 What we’ll learn today:! 1. 1. Glaciers and where they occur! 2. 2. Compare depositional and erosional features of glaciers! 3. 3. Earth-Sun orbital parameters, relevance to interglacial periods ! A glacier is a river of ice. Glaciers can range in size from: 100s of m (mountain glaciers) to 100s of km (continental ice sheets) Most glaciers are 1000s to 100,000s of years old! The Snowline is the lowest elevation of a perennial (2 yrs) snow field. Glaciers can only form above the snowline, where snow does not completely melt in the summer. Requirements: Cold temperatures Polar latitudes or high elevations Sufficient snow Flat area for snow to accumulate Permafrost is permanently frozen soil beneath a seasonal active layer that supports plant life Glaciers are made of compressed, recrystallized snow. Snow buildup in the zone of accumulation flows downhill into the zone of wastage. Glacier-Covered Areas Glacier Coverage (km2) No glaciers in Australia! 160,000 glaciers total 47 countries have glaciers 94% of Earth’s ice is in Greenland and Antarctica Mountain Glaciers are Retreating Worldwide The Antarctic Ice Sheet The Greenland Ice Sheet Glaciers flow downhill through ductile (plastic) deformation & by basal sliding. Brittle deformation near the surface makes cracks, or crevasses. Antarctic ice sheet: ductile flow extends into the ocean to form an ice shelf. Wilkins Ice shelf Breakup http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XUltAHerfpk The Greenland Ice Sheet has fewer and smaller ice shelves. Erosional Features Unique erosional landforms remain after glaciers melt. -

Minimal Geological Methane Emissions During the Younger Dryas-Preboreal Abrupt Warming Event

UC San Diego UC San Diego Previously Published Works Title Minimal geological methane emissions during the Younger Dryas-Preboreal abrupt warming event. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1j0249ms Journal Nature, 548(7668) ISSN 0028-0836 Authors Petrenko, Vasilii V Smith, Andrew M Schaefer, Hinrich et al. Publication Date 2017-08-01 DOI 10.1038/nature23316 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California LETTER doi:10.1038/nature23316 Minimal geological methane emissions during the Younger Dryas–Preboreal abrupt warming event Vasilii V. Petrenko1, Andrew M. Smith2, Hinrich Schaefer3, Katja Riedel3, Edward Brook4, Daniel Baggenstos5,6, Christina Harth5, Quan Hua2, Christo Buizert4, Adrian Schilt4, Xavier Fain7, Logan Mitchell4,8, Thomas Bauska4,9, Anais Orsi5,10, Ray F. Weiss5 & Jeffrey P. Severinghaus5 Methane (CH4) is a powerful greenhouse gas and plays a key part atmosphere can only produce combined estimates of natural geological in global atmospheric chemistry. Natural geological emissions and anthropogenic fossil CH4 emissions (refs 2, 12). (fossil methane vented naturally from marine and terrestrial Polar ice contains samples of the preindustrial atmosphere and seeps and mud volcanoes) are thought to contribute around offers the opportunity to quantify geological CH4 in the absence of 52 teragrams of methane per year to the global methane source, anthropogenic fossil CH4. A recent study used a combination of revised 13 13 about 10 per cent of the total, but both bottom-up methods source δ C isotopic signatures and published ice core δ CH4 data to 1 −1 2 (measuring emissions) and top-down approaches (measuring estimate natural geological CH4 at 51 ± 20 Tg CH4 yr (1σ range) , atmospheric mole fractions and isotopes)2 for constraining these in agreement with the bottom-up assessment of ref. -

The Definition of El Niño

The Definition of El Niño Kevin E. Trenberth National Center for Atmospheric Research,* Boulder, Colorado ABSTRACT A review is given of the meaning of the term “El Niño” and how it has changed in time, so there is no universal single definition. This needs to be recognized for scientific uses, and precision can only be achieved if the particular definition is identified in each use to reduce the possibility of misunderstanding. For quantitative purposes, possible definitions are explored that match the El Niños identified historically after 1950, and it is suggested that an El Niño can be said to occur if 5-month running means of sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies in the Niño 3.4 region (5°N–5°S, 120°–170°W) exceed 0.4°C for 6 months or more. With this definition, El Niños occur 31% of the time and La Niñas (with an equivalent definition) occur 23% of the time. The histogram of Niño 3.4 SST anomalies reveals a bimodal char- acter. An advantage of such a definition is that it allows the beginning, end, duration, and magnitude of each event to be quantified. Most El Niños begin in the northern spring or perhaps summer and peak from November to January in sea surface temperatures. 1. Introduction received into account. A brief review is given of the various uses of the term and attempts to define it. It is The term “El Niño” has evolved in its meaning even more difficult to come up with a satisfactory over the years, leading to confusion in its use. -

Blue Intensity for Dendroclimatology: Should We Have the Blues?

Dendrochronologia 32 (2014) 191–204 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Dendrochronologia jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dendro ORIGINAL ARTICLE Blue intensity for dendroclimatology: Should we have the blues? Experiments from Scotland a,∗ b c c Milosˇ Rydval , Lars-Åke Larsson , Laura McGlynn , Björn E. Gunnarson , d d a Neil J. Loader , Giles H.F. Young , Rob Wilson a School of Geography and Geosciences, University of St Andrews, UK b Cybis Elektronik & Data AB, Saltsjöbaden, Sweden c Department of Physical Geography and Quaternary Geology, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden d Department of Geography, Swansea University, Swansea, UK a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Blue intensity (BI) has the potential to provide information on past summer temperatures of a similar Received 1 April 2014 quality to maximum latewood density (MXD), but at a substantially reduced cost. This paper provides Accepted 27 April 2014 a methodological guide to the generation of BI data using a new and affordable BI measurement sys- tem; CooRecorder. Focussing on four sites in the Scottish Highlands from a wider network of 42 sites Keywords: developed for the Scottish Pine Project, BI and MXD data from Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) were used Blue intensity to facilitate a direct comparison between these parameters. A series of experiments aimed at identify- Maximum latewood density ing and addressing the limitations of BI suggest that while some potential limitations exist, these can Scots pine Dendroclimatology be minimised by adhering to appropriate BI generation protocols. The comparison of BI data produced using different resin-extraction methods (acetone vs. -

Cryosphere: a Kingdom of Anomalies and Diversity

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 6535–6542, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-6535-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Cryosphere: a kingdom of anomalies and diversity Vladimir Melnikov1,2,3, Viktor Gennadinik1, Markku Kulmala1,4, Hanna K. Lappalainen1,4,5, Tuukka Petäjä1,4, and Sergej Zilitinkevich1,4,5,6,7,8 1Institute of Cryology, Tyumen State University, Tyumen, Russia 2Industrial University of Tyumen, Tyumen, Russia 3Earth Cryosphere Institute, Tyumen Scientific Center SB RAS, Tyumen, Russia 4Institute for Atmospheric and Earth System Research (INAR), Physics, Faculty of Science, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland 5Finnish Meteorological Institute, Helsinki, Finland 6Faculty of Radio-Physics, University of Nizhny Novgorod, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia 7Faculty of Geography, University of Moscow, Moscow, Russia 8Institute of Geography, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia Correspondence: Hanna K. Lappalainen (hanna.k.lappalainen@helsinki.fi) Received: 17 November 2017 – Discussion started: 12 January 2018 Revised: 20 March 2018 – Accepted: 26 March 2018 – Published: 8 May 2018 Abstract. The cryosphere of the Earth overlaps with the 1 Introduction atmosphere, hydrosphere and lithosphere over vast areas ◦ with temperatures below 0 C and pronounced H2O phase changes. In spite of its strong variability in space and time, Nowadays the Earth system is facing the so-called “Grand the cryosphere plays the role of a global thermostat, keeping Challenges”. The rapidly growing population needs fresh air the thermal regime on the Earth within rather narrow limits, and water, more food and more energy. Thus humankind suf- affording continuation of the conditions needed for the main- fers from climate change, deterioration of the air, water and tenance of life. -

Geography and Atmospheric Science 1

Geography and Atmospheric Science 1 Undergraduate Research Center is another great resource. The center Geography and aids undergraduates interested in doing research, offers funding opportunities, and provides step-by-step workshops which provide Atmospheric Science students the skills necessary to explore, investigate, and excel. Atmospheric Science labs include a Meteorology and Climate Hub Geography as an academic discipline studies the spatial dimensions of, (MACH) with state-of-the-art AWIPS II software used by the National and links between, culture, society, and environmental processes. The Weather Service and computer lab and collaborative space dedicated study of Atmospheric Science involves weather and climate and how to students doing research. Students also get hands-on experience, those affect human activity and life on earth. At the University of Kansas, from forecasting and providing reports to university radio (KJHK 90.7 our department's programs work to understand human activity and the FM) and television (KUJH-TV) to research project opportunities through physical world. our department and the University of Kansas Undergraduate Research Center. Why study geography? . Because people, places, and environments interact and evolve in a changing world. From conservation to soil science to the power of Undergraduate Programs geographic information science data and more, the study of geography at the University of Kansas prepares future leaders. The study of geography Geography encompasses landscape and physical features of the planet and human activity, the environment and resources, migration, and more. Our Geography integrates information from a variety of sources to study program (http://geog.ku.edu/degrees/) has a unique cross-disciplinary the nature of culture areas, the emergence of physical and human nature with pathway options (http://geog.ku.edu/geography-pathways/) landscapes, and problems of interaction between people and the and diverse faculty (http://geog.ku.edu/faculty/) who are passionate about environment. -

Murphey Et Al. 2019 Best Practices in Mitigation Paleontology

PROCEEDINGS of the San Diego Society of Natural History Founded 1874 Number 47 1 May 2019 BEST PRACTICES IN MITIGATION PALEONTOLOGY By Paul C. Murphey Paleo Solutions, 2785 Speer Boulevard, Suite 1, Denver, CO 80211, U.S.A.; [email protected]; Department of Paleontology, San Diego Natural History Museum, 1788 El Prado, San Diego, CA 92101, U.S.A.; [email protected] Department of Earth Sciences, Denver Museum of Nature and Science, 2001 Colorado Boulevard, Denver, CO 80201, U.S.A. Georgia E. Knauss SWCA Environmental Consultants, 1892 S. Sheridan Avenue, Sheridan, WY 82801 U.S.A.; [email protected] Lanny H. Fisk PaleoResource Consultants, 550 High Street, Suite 108, Auburn, CA 95603, U.S.A. (deceased) Thomas A. Deméré Department of Paleontology, San Diego Natural History Museum, 1788 El Prado, San Diego, CA 92101, U.S.A.; [email protected] Robert E. Reynolds Department of Paleontology, San Diego Natural History Museum, 1788 El Prado, San Diego, CA 92101, U.S.A.; [email protected] For correspondence, write to: Paul C. Murphey, Paleo Solutions, 4614 Lonespur Ct. Oceanside, CA 92056 Email: [email protected] [email protected] bpmp-19-01-fm Page 2 PDF Created: 2019-4-12: 9:20:AM 2 Paul C. Murphey, Georgia E. Knauss, Lanny H. Fisk, Thomas A. Deméré, and Robert E. Reynolds TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract . 4 Introduction . 4 History and Scientific Contributions . 5 History of Mitigation Paleontology in the United States . 5 Methods Best Practice Categories . 7 1. Qualifications. 7 Confusion between Resource Disciplines . 7 Professional Geologists as Mitigation Paleontologists. 8 Mitigation Paleontologist Categories .