Security Vetting, Race and Whitehall, 1945 – 1968 Lomas, DWB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/65f2825x Author Young, Mark Thomas Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Mark Thomas Young June 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Steven Gould Axelrod Dr. Tom Lutz Copyright by Mark Thomas Young 2015 The Dissertation of Mark Thomas Young is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As there are many midwives to an “individual” success, I’d like to thank the various mentors, colleagues, organizations, friends, and family members who have supported me through the stages of conception, drafting, revision, and completion of this project. Perhaps the most important influences on my early thinking about this topic came from Paweł Frelik and Larry McCaffery, with whom I shared a rousing desert hike in the foothills of Borrego Springs. After an evening of food, drink, and lively exchange, I had the long-overdue epiphany to channel my training in musical performance more directly into my academic pursuits. The early support, friendship, and collegiality of these two had a tremendously positive effect on the arc of my scholarship; knowing they believed in the project helped me pencil its first sketchy contours—and ultimately see it through to the end. -

Spooks Returns to Dvd

A BAPTISM OF FIRE FOR THE NEW TEAM AS SPOOKS RETURNS TO DVD SPOOKS: SERIES NINE AVALIABLE ON DVD FROM 28TH FEBRUARY 2011 “Who doesn’t feel a thrill of excitement when a new series of Spooks hits our screens?” Daily Mail “It’s a tribute to Spooks’ staying power that after eight years we still care so much” The Telegraph BAFTA Award‐winning British television spy drama Spooks is back for its ninth knuckle‐clenching series and is available on DVD from 28th February 2011 courtesy of Universal Playback. Filled with spy‐tastic extra features, the DVD is a must for any die‐hard Spooks fan. The ninth series of the critically acclaimed Spooks, is filled with dramatic revelations and a host of new characters ‐ Sophia Myles (Underworld, Doctor Who), Max Brown (Mistresses, The Tudors), Iain Glen (The Blue Room, Lara Croft: Tomb Raider), Simon Russell Beale (Much Ado About Nothing, Uncle Vanya) and Laila Rouass (Primeval, Footballers’ Wives). Friendships will be tested and the depth of deceit will lead to an unprecedented game of cat and mouse and the impact this has on the team dynamic will have viewers enthralled. Follow the team on a whirlwind adventure tracking Somalian terrorists, preventing assassination attempts, avoiding bomb efforts and vicious snipers, and through it all face the personal consequences of working for the MI5. The complete Spooks: Series 9 DVD boxset contains never before seen extras such as a feature on The Cost of Being a Spy and a look at The Downfall of Lucas North. Episode commentaries with the cast and crew will also reveal secrets that have so far remained strictly confidential. -

Army to Hold War Game on Thursday Volleyball Club Niš Are a Professional Volleyball Team Based in Niš, Serbia and Play in the Serbian Volley League

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 8 Pages+4 Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 42nd year No.13757 Thursday SEPTEMBER 10, 2020 Shahrivar 20, 1399 Muharram 21, 1442 Senator Murphy calls Skocic talks about Condensate Tehran academic center Pompeo’s remarks on Iran’s his footballing output reaches picks “Les Misérables” for uranium stockpile funny 2 dreams 3 650,000 bpd 4 book reading contest 8 Iran slams West’s hypocrisy on freedom SPECIAL ISSUE of expression TEHRAN — In an indirect reference to the republication of cartoons insulting the Holy Prophet of Islam (PBUH) by the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif Conspiracy on Wednesday slammed “institutional- ized hypocrisy” under the pretext of the freedom of expression. “Freedom of Expression? Or Institutionalized Hypocrisy? 2 Steel ingot output or not? increases 7% in 5 months yr/yr TEHRAN — Production of steel ingot in Iran increased seven percent during the first five months of the current Irani- an calendar year (March 20-August 21) compared to the same period of time in the past year, IRNA reported. As reported, over 9.238 million tons of steel ingot was produced during the five- month period of the present year. 4 Designs from Iran shortlisted for Dezeen Awards 2020 By Seyyed Mostafa Mousavi Sabet TEHRAN — Designs of the Nur-e Mobin Primary School and the Kohan Ceram Central Office created by Iranian archi- File photo tects have been shortlisted for the Dezeen Awards 2020 in London. -

DEVELOPING a HAUNTOLOGY of the BLACK BODY Kashif Jerome

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository SPECTERS AND SPOOKS: DEVELOPING A HAUNTOLOGY OF THE BLACK BODY Kashif Jerome Powell, MA A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Department of Communication Studies. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Renee Alexander-Craft Ashley Lucas Della Pollock Alvaro Reyes Eric King Watts © 2014 Kashif Jerome Powell ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kashif Jerome Powell: Specters and Spooks: Developing a Hauntology of The Black Body (Under the direction of Dr. Renee Alexander-Craft) This dissertation utilizes theories of embodiment and performance to develop a “hauntology of blackness,” which investigates imaginative sites of death constructed through the historical, social, and performative facets of institutional slavery in the United States to theorize notions of blackness and the black body. I argue that the relationship between the black body and death have conjured a death-driven specter that manifest historically, performatively, visually, and phenomenally as blackness. The rise and continual return of this “specter of blackness” positions the black body in the United States as a body “haunted” by its own biological and phenotypical disposition. Placing the theory of Jacques Derrida and Frantz Fanon in conversation with scholars such as Avery Gordon, Saidiya Hartman, Toni Morrison, and others, I evoke the language of haunting to consider the profound effect the relationship between the black body and death has had on ontological, psychoanalytic, and phenomenological understandings of blackness within post-modernity. -

Creep Through the Decades Legend Has It: Denton’S Retro Cult Classics for Your Halloween Watchlist Haunted History

Thursday, October 31, 2019 Vol. 106, No. 3 TEXAS WOMAN’S UNIVERSITY Your student newspaper since 1914 Never A Dull Moment N THIS ISSUE HAUNTINGS | CAMP OAKLEY I : How to craft a last minute costume 7 Boo at the U: photo set 3 An introvert’s guide to the perfect HAPPY HALLOWEEN! Halloween night in 7 Graphic by Angelica Monsour. SCARES | HALLOWEEN MOVIES HAUNTS | LOCAL LEGENDS Creep through the decades Legend has it: Denton’s Retro cult classics for your Halloween watchlist haunted history By AMBER GAUDET By ALYSSA WALKER with one of his workers. The work- er was charged with murder, but o October is complete without very town has stories eventually was found not guilty. Na good Halloween movie binge- Eoriginating from years There have been rumors of fest. Even if you’re not into horror, ago that have changed over footsteps and moans being heard the last few decades have offered time, morphing into unset- from the upstairs bedroom, a face plenty of spooky favorites to satisfy tling legends that haunt locals that appears in the attic window your craving for Halloween nostalgia. — and Denton is no exception. and a photograph with eyes that 1970s There are some stories that ev- follow you everywhere you walk. In the aftermath of the Manson family ery Dentonite has explored or at The police have even been called killings, the midst of the Vietnam War, least heard of, like the Old Goat- after employees were spooked by and the scandal of Watergate, the ‘70s were man’s Bridge or the purple door on sounds in the house. -

Coup in Iran: Thugs, Turncoats, Soldiers, and Spooks Ali Rahnema Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-07606-8 - Behind the 1953 Coup in Iran: Thugs, Turncoats, Soldiers, and Spooks Ali Rahnema Frontmatter More information Behind the 1953 Coup in Iran Thugs, Turncoats, Soldiers, and Spooks Ali Rahnema’s newest work is a meticulous historical reconstruction of the events surrounding the Iranian coup d’état of 1953 that led to the overthrow of Mohammed Mosaddeq and his government. Mosaddeq’s removal from power has probably attracted more attention than any other event that occurred during his tenure because of the role of foreign involvement; the political, economic and social impact on Iran; and the long-term impact the ousting had on Iran–US relations. Drawing on a wealth of American, British and Iranian sources, Rahnema closely examines the four-day period between the first failed coup and the second successful attempt, investigating in fine detail how the two coups were conceptualized, rationalized and then executed by players on both the Anglo-American and Iranian sides. Through pains- taking research into little-studied sources, Rahnema casts new light on how a small group of highly influential pro-Britain politicians and power brokers with important connections revisited the realities on the ground with the CIA operatives dispatched to Iran and how they recalibrated a new – and ultimately successful – operational plan. Ali Rahnema is Professor of Economics and director of the master’s programme in Middle East and Islamic studies at the American University of Paris. His publications include Superstition as Ideology in Iranian Politics (Cambridge, 2011) and An Islamic Utopian: A Political Biography of Ali Shariati, second edition (2014). -

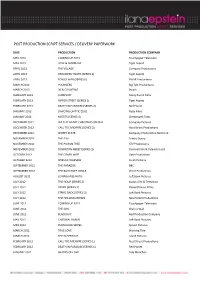

Post Production Script Services / Delivery Paperwork

POST PRODUCTION SCRIPT SERVICES / DELIVERY PAPERWORK DATE PRODUCTION PRODUCTION COMPANY MAY 2013 COMING UP 2013 Touchpaper Television MAY 2013 LOVE & MARRIAGE Tiger Aspect APRIL 2013 THE VILLAGE Company Productions APRIL 2013 PRISONERS’ WIVES (SERIES 2) Tiger Aspect APRIL 2013 FOYLES WAR (SERIES 8) FWAR Productions MARCH 2013 YOUNGERS Big Talk Productions MARCH 2013 30 & COUNTING Bwark FEBRUARY 2013 COMPLICIT Many Rivers Films FEBRUARY 2013 RIPPER STREET (SERIES 1) Tiger Aspect FEBRUARY 2013 DEATH IN PARADISE (SERIES 2) Red Planet JANUARY 2013 DANCING ON THE EDGE Ruby Films JANUARY 2013 MISFITS (SERIES 4) Clerkenwell Films DECEMBER 2012 WILD AT HEART CHRISTMAS SPECIAL Company Pictures DECEMBER 2012 CALL THE MIDWIFE (SERIES 2) Neal Street Productions DECEMBER 2012 SECRET STATE Company Productions North Ltd NOVEMBER 2012 THE FALL Artists Studio NOVEMBER 2012 THE POISON TREE STV Productions NOVEMBER 2012 DOWNTON ABBEY (SERIES 3) Carnival Film & Television Ltd OCTOBER 2012 THE OTHER WIFE Gate Productions OCTOBER 2012 SPIES OF WARSAW Fresh Pictures SEPTEMBER 2012 THE PARADISE BBC SEPTEMBER 2012 THE BLETCHLEY CIRCLE Word Productions AUGUST 2012 LOVING MISS HATO Left Bank Pictures JULY 2012 THE HOUR (SERIES 2) Kudos Film & Television JULY 2012 VEXED (SERIES 2) Eleventh Hour Films JULY 2012 STRIKE BACK (SERIES 3) Left Bank Pictures JULY 2012 THE HOLLOW CROWN Neal Street Productions JUNE 2012 COMING UP 2012 Touchpaper Television JUNE 2012 THE GIRL Wall to Wall JUNE 2012 BLACKOUT Red Production Company MAY 2012 CARDINAL BURNS Left Bank Pictures -

Spooks Rules

TM You don’t have to outrun the monsters . if you can outrun your friends. a card game for 3 or more players Spooks is a fast-moving party game in which you play cards The Cat is played. It is the “wild card,” so it can be played on by matching numbers and suits. The first player to empty his hand anything. (See the rules for the Cat below.) wins . and the ghosties get everybody else! A Goblin, Bones, or Bat card is played as the next card in There are 11 cards in each suit (Spiders, Spooks, Goblins, sequence. (See the rules for Goblins, Bones, and Bats below.) Bones, and Bats) – 1 through 10, plus the Master – and one Black Cat card. Each suit has a special rule for play, so the last card played can change everything. Who will be first to play all his TRICKY GOBLINS cards and escape the haunted house? Goblins love to play tricks. The only way to escape their wicked game is to play with them. SPIDERS AND SPOOKS! The Goblin cards are green. When a Goblin is played, each player chooses a card from his hand and puts it face-down in You knew better than to let your friends talk you into this “adventure” . front of him – not on the discard pile! You may choose a but you came anyway. Now the door Goblin to try to win the trick, or you may “slough” a card of yawns open, revealing spiders every- another suit. where, and noises that might be the wind, When everyone has chosen a card, turn all cards face up. -

Data Epistemologies / Surveillance and Uncertainty

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2016 Data Epistemologies / Surveillance and Uncertainty Sun Ha Hong University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Communication Commons, Other Sociology Commons, and the Philosophy of Science Commons Recommended Citation Hong, Sun Ha, "Data Epistemologies / Surveillance and Uncertainty" (2016). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1766. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1766 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1766 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Data Epistemologies / Surveillance and Uncertainty Abstract Data Epistemologies studies the changing ways in which ‘knowledge’ is defined, promised, problematised, legitimated vis-á-vis the advent of digital, ‘big’ data surveillance technologies in early twenty-first century America. As part of the period’s fascination with ‘new’ media and ‘big’ data, such technologies intersect ambitious claims to better knowledge with a problematisation of uncertainty. This entanglement, I argue, results in contextual reconfigurations of what ‘counts’ as knowledge and who (or what) is granted authority to produce it – whether it involves proving that indiscriminate domestic surveillance prevents terrorist attacks, to arguing that machinic sensors can know us better than we can ever know ourselves. The present work focuses on two empirical cases. The first is the ‘Snowden Affair’ (2013-Present): the public controversy unleashed through the leakage of vast quantities of secret material on the electronic surveillance practices of the U.S. government. The second is the ‘Quantified Self’ (2007-Present), a name which describes both an international community of experimenters and the wider industry built up around the use of data-driven surveillance technology for self-tracking every possible aspect of the individual ‘self’. -

Introduction

Introduction At the conclusion of John le Carré’s novel Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1974), the charismatic traitor at the heart of British intelligence articulates one of the key themes of le Carré’s work, declaring his belief that ‘secret services were the only real measure of a nation’s political health, the only real expression of its subconscious’.1 When five years later the novel was adapted for television by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), this metaphor would acquire an additional layer. Asked by director John Irvin how the interior spaces of the intelligence service should be depicted on-screen, le Carré was said to have replied that ‘the dusty offices, the corridors, the elderly office furniture and even the anxiously cranking lifts of MI5 felt like, looked like and had some of the same kinds of people – as the BBC.’2 In fact, this point of comparison was neither unique nor histori- cally specific. Twenty-three years later writer David Wolstencroft was devising the format for a new original BBC spy series which depicted the activities of a counter-terror section within the British Security Service (MI5). In a later Radio Times interview he admitted to the impossibility of gaining access to the real MI5 as part of his research for Spooks (BBC 1, 2002–11), but noted that ‘having been in the BBC quite a lot, I wondered whether it wasn’t quite a good model.’3 Yet the BBC of the 2000s that Wolstencroft used as his inspiration was a very different place to that described by le Carré in the late 1970s. -

Adapt Language Models to Domains and Tasks

Don’t Stop Pretraining: Adapt Language Models to Domains and Tasks Suchin Gururangany Ana Marasovic´y} Swabha Swayamdiptay Kyle Loy Iz Beltagyy Doug Downeyy Noah A. Smithy} yAllen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, Seattle, WA, USA }Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA fsuching,anam,swabhas,kylel,beltagy,dougd,[email protected] Abstract Language models pretrained on text from a wide variety of sources form the foundation of today’s NLP. In light of the success of these broad-coverage models, we investigate whether it is still helpful to tailor a pretrained model to the domain of a target task. We present a study across four domains (biomedi- cal and computer science publications, news, and reviews) and eight classification tasks, showing that a second phase of pretraining in- domain (domain-adaptive pretraining) leads to performance gains, under both high- and Figure 1: An illustration of data distributions. Task low-resource settings. Moreover, adapting data is comprised of an observable task distribution, to the task’s unlabeled data (task-adaptive usually non-randomly sampled from a wider distribu- pretraining) improves performance even after tion (light grey ellipsis) within an even larger target do- domain-adaptive pretraining. Finally, we show main, which is not necessarily one of the domains in- that adapting to a task corpus augmented us- cluded in the original LM pretraining domain – though ing simple data selection strategies is an effec- overlap is possible. We explore the benefits of contin- tive alternative, especially when resources for ued pretraining on data from the task distribution and domain-adaptive pretraining might be unavail- the domain distribution. -

11-12 Wisconsin

Page 78 MidWest Outdoors Wisconsin Section “Helping People Enjoy the Outdoors” November 2012 Hard Water Perch Fishing Hunter W. of Joliet, Ill., caught this Melvin Grasser of Milwaukee, Wis., jumbo perch while fishing with his caught this jumbo perch while fish- parents and the author in the begin- ing with the author in January of Duncan Bachman and his granddaughter, Becky Bauchman, caught these ning of March 2012. 2012. perch while fishing with the author on a windy, cold, January day, inside one of his 12 heated and insulated ice houses. BY JOHN ANDREW describing what we use and what works for us. Tying on small ice jigs or small ice As winter is fast approaching, some hooks in the size range of 1/64 or 1/32 people have already started ice fishing on ounce is standard and normal. the smaller ponds in our northern region. Using a spring tip rod is very common. As a year ‘round tour guide for fishing, my This tip is made out of very soft spring clients are very excited to catching perch material and allows you to see the tip of through the ice. These tasty fish offer your rod move even at the most gentle of some of the best table fair for the winter bites from a fish. Although, I like to have sportsman. my guests use a tiny slip bobber (which I With my 12 wood, heated and insulat- have installed before they get there). This ed ice houses on seven different lakes, the is much easier for them to see and to guests are always catching fish at one of focus their attention on, by looking down these many locations.