The Pacific King and the Militant Prince?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Art Studies September 2020 Elizabethan and Jacobean

British Art Studies September 2020 Elizabethan and Jacobean Miniature Paintings in Context Edited by Catharine MacLeod and Alexander Marr British Art Studies Issue 17, published 30 September 2020 Elizabethan and Jacobean Miniature Paintings in Context Edited by Catharine MacLeod and Alexander Marr Cover image: Left portrait: Isaac Oliver, Ludovick Stuart, 2nd Duke of Lennox, later Duke of Richmond, ca. 1605, watercolour on vellum, laid onto table-book leaf, 5.7 x 4.4 cm. Collection of National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG 3063); Right portrait: Isaac Oliver, Ludovick Stuart, 2nd Duke of Lennox, later Duke of Richmond, ca. 1603, watercolour on vellum, laid on card, 4.9 x 4 cm. Collection of Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (FM 3869). Digital image courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, London (All rights reserved); Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (All rights reserved). PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. -

British Art Studies September 2020 Elizabethan and Jacobean Miniature Paintings in Context Edited by Catharine Macleod and Alexa

British Art Studies September 2020 Elizabethan and Jacobean Miniature Paintings in Context Edited by Catharine MacLeod and Alexander Marr British Art Studies Issue 17, published 30 September 2020 Elizabethan and Jacobean Miniature Paintings in Context Edited by Catharine MacLeod and Alexander Marr Cover image: Left portrait: Isaac Oliver, Ludovick Stuart, 2nd Duke of Lennox, later Duke of Richmond, ca. 1605, watercolour on vellum, laid onto table-book leaf, 5.7 x 4.4 cm. Collection of National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG 3063); Right portrait: Isaac Oliver, Ludovick Stuart, 2nd Duke of Lennox, later Duke of Richmond, ca. 1603, watercolour on vellum, laid on card, 4.9 x 4 cm. Collection of Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (FM 3869). Digital image courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, London (All rights reserved); Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (All rights reserved). PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. -

Student Name Field: Early Modern Europe Courses Taken for Ion C

Student Name Field: Early Modern Europe Courses Taken for Concentration Credit Fall 2005 Freshman Seminar 39u – Henri Zerner Focused on the development of Printmaking, Art and print culture and art with the Communication advent of the printing press in the fifteenth century, and subsequent printing techniques that developed, such as woodblock, engraving, etc. Looked at original artwork and prints and studied how the medium was used to communicate ideas and styles of art Spring 2006 History of Art and Henri Zerner A survey of western art Architecture 10 – The Western historical trends from the early Tradition Renaissance to the present, focusing on particular artists or movements representative of art historical periods but by no means encompassing the entire history. Spring 2006 English 146 – Sex and Lynne Festa A study of evolving concepts of Sensibility in the Enlightenment literary personas in the English Enlightenment from Eliza Haywood’s Philidore and Placentia (1727) to Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility (1811). We looked at changing gender roles in print material and literature, as well as developing concepts of the human body and 20th century analyses of these trends, focusing particularly on Foucault’s A History of Sexuality. Fall 2006 History of Art and Frank A look into trends of art and Architecture 152 – The Italian Fehrenbach inventions specific to the Renaissance Italian Renaissance, looking at the origins of these trends in Medieval Italian Art (from the ninth century at the earliest ) and following them through late sixteenth century mannerism. Focused particularly on the invention of single‐point perspective, oil painting, sculptural trends and portraiture. -

Anecdotes of Painting in England : with Some Account of the Principal

C ' 1 2. J? Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/paintingineng02walp ^-©HINTESS <0>F AEHJKTID 'oat/ /y ' L o :j : ANECDOTES OF PAINTING IN ENGLAND; WITH SOME ACCOUNT OF THE PRINCIPAL ARTISTS; AND INCIDENTAL NOTES ON OTHER ARTS; COLLECTED BY THE LATE MR. GEORGE VERTUE; DIGESTED AND PUBLISHED FROM HIS ORIGINAL MSS. BY THE HONOURABLE HORACE WALPOLE; WITH CONSIDERABLE ADDITIONS BY THE REV. JAMES DALLAWAY. LONDON PRINTED AT THE SHAKSPEARE PRESS, BY W. NICOL, FOR JOHN MAJOR, FLEET-STREET. MDCCCXXVI. LIST OF PLATES TO VOL. II. The Countess of Arundel, from the Original Painting at Worksop Manor, facing the title page. Paul Vansomer, . to face page 5 Cornelius Jansen, . .9 Daniel Mytens, . .15 Peter Oliver, . 25 The Earl of Arundel, . .144 Sir Peter Paul Rubens, . 161 Abraham Diepenbeck, . 1S7 Sir Anthony Vandyck, . 188 Cornelius Polenburg, . 238 John Torrentius, . .241 George Jameson, his Wife and Son, . 243 William Dobson, . 251 Gerard Honthorst, . 258 Nicholas Laniere, . 270 John Petitot, . 301 Inigo Jones, .... 330 ENGRAVINGS ON WOOD. Arms of Rubens, Vandyck & Jones to follow the title. Henry Gyles and John Rowell, . 39 Nicholas Stone, Senior and Junior, . 55 Henry Stone, .... 65 View of Wollaton, Nottinghamshire, . 91 Abraham Vanderdort, . 101 Sir B. Gerbier, . .114 George Geldorp, . 233 Henry Steenwyck, . 240 John Van Belcamp, . 265 Horatio Gentileschi, . 267 Francis Wouters, . 273 ENGRAVINGS ON WOOD continued. Adrian Hanneman, . 279 Sir Toby Matthews, . , .286 Francis Cleyn, . 291 Edward Pierce, Father and Son, . 314 Hubert Le Soeur, . 316 View of Whitehall, . .361 General Lambert, R. Walker and E. Mascall, 368 CONTENTS OF THE SECOND VOLUME. -

From Allegory to Domesticity and Informality, Elizabeth I and Elizabeth II

The Image of the Queen; From Allegory to Domesticity and Informality, Elizabeth I and Elizabeth II. By Mihail Vlasiu [Master of Philosophy Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow] Christie’s Education London Master’s Programme September 2000 © Mihail Vlasiu ProQuest Number: 13818866 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818866 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 GLASGOW 1 u n iv er sity .LIBRARY: \1S3lS Abstract This thesis focuses on issues of continuity and change in the evolution royal portraiture and examines the similarities and differences in portraying Elizabeth I in the 16th and 17th centuries and Elizabeth II in the 20th century. The thesis goes beyond the similarity of the shared name of the two monarchs; it shows the major changes not only in the way of portraying a queen but also in the way in which the public has changed its perception of the monarch and of the monarchy. Elizabeth I aimed to unite a nation by focusing the eye upon herself, while Elizabeth II triumphed through humanity and informality. -

Miniatura; Or, the Art of Limning

A/a 3 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY FROM °'^' ^'^^ ^'^ °' limning, iiiiiiiiiiii?'""' 3 1924 016 785 572 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924016785572 MINIATURA OR THE ART OF LIMNING Oxford University Press London Edinburgh GJasgoiv t^eiv York Toronto Melbourne Cape Tonvn Bombay Humphrey Milford Publisher to the University MINIATURA or The Art of Limning By ET>]V^RT> KORGATE Edited from the Manuscript in the Bodleian Library and Collated with other Manuscripts by MARTIN HARDIE OXFORD At the CLARENDON PRESS MDCCCCXIX ;-H:ii»d in Sii. 6' INTRODUCTION In the year 1735: seven carts trundled along the road from Norwich to Oxford carrying the great collection of books and manuscripts bequeathed to the Bodleian Library by Thomas Tanner, Bishop of St. Asaph. In one of these carts was the manu- script of Edward Norgate's 'Miniatura', bearingon its fly-leaf, in the tremulous writing of old age, the signature of its previous owner, Sir John Holland,^ and his inscription, a common one in seven- teenth-century books of recipes, Secreta mea mihi. The manuscript comprises forty-four folio pages containing a treatise on ' Miniatura or the Art of Limning'jfollowed by nine folio pages of recipes for colours and perfumes. The water-mark of the paper on which the treatise is written is an elaborate ' pot mark ', closely resembling in design the marks on papers of 1^34. and 16^43 preserved in the Town Hall, Rochester. -

Beyond the Mask: Strategic Symbolism in the Rainbow Portrait

Beyond the Mask: Strategic Symbolism in the Rainbow Portrait Christa Wilson English Faculty advisor: Dr. Paige Reynolds Out of all the known portraits of Queen Elizabeth I, the Rainbow Portrait has long been viewed as one of the most mysterious by viewers and scholars alike. What is often overlooked in the examination of its complex iconography, however, is the direct correlation that exists between the painting’s striking symbolic imagery and the particular issues confronting Elizabeth at the time when the portrait was made. Ultimately, the portrait reflects a desire to reaffirm the Queen’s authority and splendor in the midst of adverse circumstances. Through its treatment of Elizabeth’s age, virtue, and power at a time when economic and political tensions in England were increasingly pronounced, the painting both reflects and responds to the anxieties of English citizens toward the end of Elizabeth’s reign. The Rainbow Portrait currently resides at Hatfield House, a residence in Hertfordshire, England, once owned by Robert Cecil, son and successor of Elizabeth’s chief minister, William Cecil. Although undated, the portrait is thought to have been painted around the year 1600 and is one of the last known portraits made of Queen Elizabeth before her death in 1603. The artist of the painting is CLA Journal 4 (2016) pp. 219-232 220 Wilson _____________________________________________________________ also unknown, but scholars have generally attributed the portrait to Isaac Oliver, a well-known French-English miniaturist of the late Elizabethan and Jacobean periods who studied under Elizabeth’s official limner, Nicholas Hilliard, and was brother-in-law to another of Elizabeth’s notable portraitists, Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger. -

Cosmetics and Whiteness in Imperial Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I

The Face of an Empire: Cosmetics and Whiteness in Imperial Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I Tara Allen-Flanagan When Queen Elizabeth I entered her fifties, she grew reluctant to sit for any more portraits. The final three portraits that she sat for—the Armada Portrait, The Ditch- ley Portrait, and the Oliver Miniature—painted between the mid-1580s and her death in 1602, portray the queen with a smooth, white face and bright coral lips and cheeks. The style of painting the queen’s face as seen in these last portraits was canonized as a pattern for future artists to follow when painting the queen during and after the last years of her reign.1 In the Elizabethan era, the English govern- ment often attempted to control how the queen was depicted in artwork; in 1596 the English Privy Council drafted a proclamation that required portraits of the queen to depict her as “beutyfull [sic] and magnanimous” as “God hathe blessed her.”2 In both art-historical scholarship and popular culture, the queen’s whitened skin and rouged lips and cheeks in her official portraiture are often cited as evi- dence of her vanity and waning looks. However, as I explore in this essay, the use of cosmetics in the early modern era was associated not only with narcissism but with England’s colonial efforts. By considering discourses about her status as a symbol of natural beauty and the racist associations with makeup application, I argue that the legibility of makeup on the queen’s face in imperial portraits and preservation of this motif as a pattern can be read as a symbol of her imperial and racial domination in the Americas and in England. -

Ham House the Green Closet Miniatures and Cabinet Pictures Ham House the Green Closet Miniatures and Cabinet Pictures a HISTORIC HANG REVIVED

Ham House The Green Closet miniatures and cabinet pictures Ham House The Green Closet miniatures and cabinet pictures A HISTORIC HANG REVIVED The collection of miniatures at Ham House is one of the largest accumulations of miniatures by one family to have remained substantially intact. Its display with small paintings and other images in an early 17th-century picture closet is without surviving parallel in England. By 1990, however, almost all the pictures and miniatures were displayed elsewhere, and the original purpose of the Green Closet was no longer evident. The substantial restoration of the historic groupings on its walls, with the kind agreement of the Victoria & Albert Museum, has revived the spirit, and much of the appearance, of the traditional arrangement. Designed to display both cabinet fring’d’ hanging from ‘guilt Curtaine rods dismantled) that extended even to the pictures and miniatures on an intimate round the roome’,which could be drawn sides of the chimneybreast. This was the scale, in contrast to the arrays of three- to protect the paintings from light and arrangement in 1844, when 97 pictures quarter-length portraits in the adjoining dust. The table and green-upholstered were listed, a considerable increase on Long Gallery, the Green Closet is of the seat furniture were also provided with 1677, when there were 57, but the spirit greatest rarity, not only as – in its core – sarsenet case-covers. Modern copies of all of the 17th-century room was a survival from the reign of Charles I these decorative and practical furnishings undoubtedly preserved. It may be that (whose own closets for the display of and fittings have recently been provided. -

Elizabethan Treasures, Miniatures by Hilliard and Oliver Exhibition Review - National Portrait Gallery, London, 21 February - 19 May 2019

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 19 | 2019 Rethinking Laughter in Contemporary Anglophone Theatre Elizabethan Treasures, Miniatures by Hilliard and Oliver Exhibition review - National Portrait Gallery, London, 21 February - 19 May 2019 Alice Leroy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/21042 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.21042 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Printed version Date of publication: 7 October 2019 Electronic reference Alice Leroy, “Elizabethan Treasures, Miniatures by Hilliard and Oliver”, Miranda [Online], 19 | 2019, Online since 09 October 2019, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ miranda/21042 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.21042 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Elizabethan Treasures, Miniatures by Hilliard and Oliver 1 Elizabethan Treasures, Miniatures by Hilliard and Oliver Exhibition review - National Portrait Gallery, London, 21 February - 19 May 2019 Alice Leroy 1 The lives, scandals, and passions of the Tudors have fascinated the general public for a long time and have been the recurring object of exhibitions in Great-Britain and abroad over the past few years.1 Although the National Portrait Gallery’s latest exhibition tackles the Renaissance period, the originality and the appeal of Elizabethan Treasures: Miniatures by Hilliard and Oliver are that it makes the conscious decision to shift the focus from a troubled royal dynasty to the artistic and cultural practices of the late 16th and early 17th centuries – in order to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Hilliard’s death, it sets aside Flemish large-scale portraiture and concentrates on one of the earliest English traditions of painting: the art of limning. -

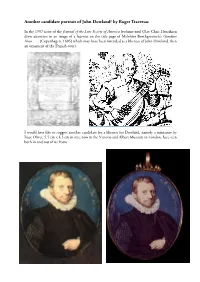

Another Candidate Portrait of John Dowland? by Roger Traversac

Another candidate portrait of John Dowland? by Roger Traversac In the 1997 issue of the Journal of the Lute Society of America (volume xxx) Olav Chris Henriksen drew attention to an image of a lutenist on the title page of Melchior Borchgrevinck’s Giardino Novo . (Copenhagen, 1605) which may have been intended as a likeness of John Dowland, then an ornament of the Danish court. I would here like to suggest another candidate for a likeness for Dowland, namely a miniature by Isaac Oliver, 5.5 cm x 4.5 cm in size, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, here seen both in and out of its frame. The caption reads ‘Anno Domini 1590 . 27th year of his age’. In the first place, this is just the right age for Dowland, born in 1563. Of course this alone hardly warrants a positive identification. Wikipedia lists a good number of ‘English Worthies’ born in that year,1 and in private communica- tion, a curator at the V&A told me that there have been a number of attempts to name the sitter of this miniature portrait. Indeed, if the ‘aetatis suae 27’ were interpreted as meaning ‘in the year at the end of which the sitter will turn 27’, the date would even fit Shakespeare or Marlowe(!), both born in 1564—but of course the miniature looks nothing like the known or presumed portraits of either. Besides the age of the sitter is there anything else which might suggest an identification with the famous lutenist? It seems to me that, allowing for the passage of 15 years, and a modest change in styling of the beard and haircut, Isaac Oliver’s sitter might be the same man as the one in the 1605 Danish engraving. -

03 Elizabethan Miniatures

Laurence Shafe - Elizabethan Miniatures Exhibition Exhibits 1. Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547-1619), Self-Portrait aged 30, 1577, V&A. Sixteenth century self-portraits are rare. 2. The role of the miniature, Drake Jewel, 1586 3. Quote from The Art of Limning with Queen Elizabeth I, by Nicholas Hilliard, 1572. Photograph: National Portrait Gallery 4. Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547-1619), Richard Hilliard, 1576-77, his father who married Laurence Wall (his master’s daughter) and had eight children 5. Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547-1619), Alice Hilliard (née Brandon), 1578, first wife of Nicholas Hilliard, his master’s daughter 6. Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547-1619), Elizabeth I Playing a Lute, c. 1575 7. Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547-1619), Sir Francis Drake, 1581, he owned the Drake Jewel, 1586 8. Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547-1619), Sir Christopher Hatton, 1588-91, full length, experimented in 1580s with different formats, also see 9. Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547-1619), George Clifford, 3rd Earl of CuMberland 10. Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547-1619), Young Man AMong Roses, c. 1587, V&A 11. Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547-1619), Young Man Clasping a Hand froM the Clouds, 1588 1 12. Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547-1619), Young Man Against FlaMes, c. 1590-1600, V&A 13. Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547-1619), Elizabeth I, c. 1600. based on Coronation Portrait painting (Anon, c. 1600) 14. Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547-1619), Self-portrait aged 30, Victoria & Albert Museum 15. Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547-1619), Sir Walter Ralegh, c. 1585, National Portrait Gallery 16. Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547-1619), Henry Percy, 9th Earl of NorthuMberland, 1590-93 17.