Back to Work: a Public Jobs Proposal for Economic Recovery 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gender Unemployment Gap

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE GENDER UNEMPLOYMENT GAP Stefania Albanesi Ayşegül Şahin Working Paper 23743 http://www.nber.org/papers/w23743 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 August 2017 We thank Raquel Fernandez, Franco Peracchi, Gille St. Paul, and participants at ESSIM 2014, the NBER Summer Institute 2012, Columbia Macro Lunch, the Society of Economic Dynamics 2011 Annual Meeting, the Federal Reserve Board’s Macro Seminar, Princeton Macro Seminar, USC Macro Seminar, SAEE-Cosme Lecture, and the St. Louis Fed Macro Seminar for helpful comments. We thank Josh Abel, Grant Graziani, Victoria Gregory, Sam Kapon, Sergey Kolbin, Christina Patterson and Joe Song for excellent research assistance. The views expressed in the paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the Federal Reserve System, or the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2017 by Stefania Albanesi and Ayşegül Şahin. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. The Gender Unemployment Gap Stefania Albanesi and Ayşegül Şahin NBER Working Paper No. 23743 August 2017 JEL No. E24,J16,J21 ABSTRACT The gender unemployment gap, the difference between female and male unemployment rates, was positive until the early 1980s. This gap disappeared after 1983, except during recessions, when men’s unemployment rate has always exceeded women’s. -

The U.S. Net Social Wage in the 21St Century

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS Working Paper Neoliberal Redistributive Policy: The U.S. Net Social Wage in the 21st Century by Katherine A. Moos Working Paper 2017-18 UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST Neoliberal Redistributive Policy: The U.S. Net Social Wage in the 21st Century Katherine A. Moos1 Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Massachusetts Amherst September 18, 2017 Abstract In this paper, I examine the trends of fiscal transfers between the state and workers during 1959 - 2012 to understand the net impact of redistributive policy in the United States. This paper presents original net social wage data from and analysis based on the replication and extension of Shaikh and Tonak (2002). The paper investigates the appearance of a post-2001 variation in the net social wage data. The positive net social wage in the 21st century is the result of a combination of factors including the growth of income support, healthcare inflation, neoliberal tax reforms, and macroeconomic instability. Growing economic inequality does not appear to alter the results of the net social wage methodology. JEL classification codes— H5 National Government Expenditures and Related Poli- cies, E62 Fiscal Policy, E64 Incomes Policy, B5 Current Heterodox Approaches Keywords— fiscal policy, net social wage, neoliberalism, social spending, taxation 1The author would like to thank Duncan Foley, Mark Setterfield, Anwar Shaikh, Jamee Moudud, Sanjay Ruparelia, and Noé M. Wiener for helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this paper. Any errors or omissions are my own. 1 1 Introduction The United States is not known for an unwavering commitment to redistributive social spending. Considered the prototypical liberal market welfare state, the United States is marked by its stingy contributory and means-tested social programs (Esping-Andersen 1990, 48). -

Estimating the Effects of Fiscal Policy in OECD Countries

Estimating the e®ects of ¯scal policy in OECD countries Roberto Perotti¤ This version: November 2004 Abstract This paper studies the e®ects of ¯scal policy on GDP, in°ation and interest rates in 5 OECD countries, using a structural Vector Autoregression approach. Its main results can be summarized as follows: 1) The e®ects of ¯scal policy on GDP tend to be small: government spending multipliers larger than 1 can be estimated only in the US in the pre-1980 period. 2) There is no evidence that tax cuts work faster or more e®ectively than spending increases. 3) The e®ects of government spending shocks and tax cuts on GDP and its components have become substantially weaker over time; in the post-1980 period these e®ects are mostly negative, particularly on private investment. 4) Only in the post-1980 period is there evidence of positive e®ects of government spending on long interest rates. In fact, when the real interest rate is held constant in the impulse responses, much of the decline in the response of GDP in the post-1980 period in the US and UK disappears. 5) Under plausible values of its price elasticity, government spending typically has small e®ects on in°ation. 6) Both the decline in the variance of the ¯scal shocks and the change in their transmission mechanism contribute to the decline in the variance of GDP after 1980. ¤IGIER - Universitµa Bocconi and Centre for Economic Policy Research. I thank Alberto Alesina, Olivier Blanchard, Fabio Canova, Zvi Eckstein, Jon Faust, Carlo Favero, Jordi Gal¶³, Daniel Gros, Bruce Hansen, Fumio Hayashi, Ilian Mihov, Chris Sims, Jim Stock and Mark Watson for helpful comments and suggestions. -

Introduction to Macroeconomics Lecture Notes

Introduction to Macroeconomics Lecture Notes Robert M. Kunst March 2006 1 Macroeconomics Macroeconomics (Greek makro = ‘big’) describes and explains economic processes that concern aggregates. An aggregate is a multitude of economic subjects that share some common features. By contrast, microeconomics treats economic processes that concern individuals. Example: The decision of a firm to purchase a new office chair from com- pany X is not a macroeconomic problem. The reaction of Austrian house- holds to an increased rate of capital taxation is a macroeconomic problem. Why macroeconomics and not only microeconomics? The whole is more complex than the sum of independent parts. It is not possible to de- scribe an economy by forming models for all firms and persons and all their cross-effects. Macroeconomics investigates aggregate behavior by imposing simplifying assumptions (“assume there are many identical firms that pro- duce the same good”) but without abstracting from the essential features. These assumptions are used in order to build macroeconomic models.Typi- cally, such models have three aspects: the ‘story’, the mathematical model, and a graphical representation. Macroeconomics is ‘non-experimental’: like, e.g., history, macro- economics cannot conduct controlled scientific experiments (people would complain about such experiments, and with a good reason) and focuses on pure observation. Because historical episodes allow diverse interpretations, many conclusions of macroeconomics are not coercive. Classical motivation of macroeconomics: politicians should be ad- vised how to control the economy, such that specified targets can be met optimally. policy targets: traditionally, the ‘magical pentagon’ of good economic growth, stable prices, full employment, external equilibrium, just distribution 1 of income; according to the EMU criteria, focus on inflation (around 2%), public debt, and a balanced budget; according to Blanchard,focusonlow unemployment (around 5%), good economic growth, and inflation (0—3%). -

Non State Employer Group Employee Guidebooks

STATE EMPLOYEE HEALTH PLAN NON-STATE GROUP EMPLOYEES BENEFIT GUIDEBOOK PLAN YEAR 2020 - 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS VENDOR CONTACT INFORMATION .............................................................................................................. 2 MEMBERSHIP ADMINISTRATION PORTAL .................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 4 GENERAL DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................................................ 5 EMPLOYEE ELIGIBILITY ................................................................................................................................ 7 OTHER ELIGIBLE INDIVIDUALS UNDER THE SEHP .................................................................................... 9 ANNUAL OPEN ENROLLMENT PERIOD ...................................................................................................... 16 MID-YEAR ENROLLMENT CHANGES .......................................................................................................... 17 LEAVE WITHOUT PAY AND RETURN FROM LEAVE WITHOUT PAY …………………………………………22 FAMILY MEDICAL LEAVE ACT(FMLA), FURLOUGHS AND LAYOFFS ……………………………………….23 HEALTH INSURANCE PORTABILITY AND ACCOUNTABILITY ACT (HIPAA) ............................................ 24 FLEXIBLE SPENDING ACCOUNT PROGRAM - 2021 .................................................................................. -

The Budgetary Effects of the Raise the Wage Act of 2021 February 2021

The Budgetary Effects of the Raise the Wage Act of 2021 FEBRUARY 2021 If enacted at the end of March 2021, the Raise the Wage Act of 2021 (S. 53, as introduced on January 26, 2021) would raise the federal minimum wage, in annual increments, to $15 per hour by June 2025 and then adjust it to increase at the same rate as median hourly wages. In this report, the Congressional Budget Office estimates the bill’s effects on the federal budget. The cumulative budget deficit over the 2021–2031 period would increase by $54 billion. Increases in annual deficits would be smaller before 2025, as the minimum-wage increases were being phased in, than in later years. Higher prices for goods and services—stemming from the higher wages of workers paid at or near the minimum wage, such as those providing long-term health care—would contribute to increases in federal spending. Changes in employment and in the distribution of income would increase spending for some programs (such as unemployment compensation), reduce spending for others (such as nutrition programs), and boost federal revenues (on net). Those estimates are consistent with CBO’s conventional approach to estimating the costs of legislation. In particular, they incorporate the assumption that nominal gross domestic product (GDP) would be unchanged. As a result, total income is roughly unchanged. Also, the deficit estimate presented above does not include increases in net outlays for interest on federal debt (as projected under current law) that would stem from the estimated effects of higher interest rates and changes in inflation under the bill. -

Minimum Wage, Official Workweek, and Overtime Compensation

ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISION POLICY NUMBER HR Division of Human Resources HR 1.84 POLICY TITLE Minimum Wage, Official Workweek, and Overtime Compensation SCOPE OF POLICY DATE OF REVISION USC System July 26, 2021 RESPONSIBLE OFFICER ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE Vice President for Human Resources Division of Human Resources THE LANGUAGE USED IN THIS DOCUMENT DOES NOT CREATE AN EMPLOYMENT CONTRACT BETWEEN THE FACULTY, STAFF, OR ADMINISTRATIVE EMPLOYEE AND THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA. THIS DOCUMENT DOES NOT CREATE ANY CONTRACTUAL RIGHTS OR ENTITLEMENTS. THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA RESERVES THE RIGHT TO REVISE THE CONTENTS OF THIS DOCUMENT, IN WHOLE OR IN PART. NO PROMISES OR ASSURANCES, WHETHER WRITTEN OR ORAL, WHICH ARE CONTRARY TO OR INCONSISTENT WITH THE TERMS OF THIS PARAGRAPH CREATE ANY CONTRACT OF EMPLOYMENT. THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA DIVISION OF HUMAN RESOURCES HAS THE AUTHORITY TO INTERPRET THE UNIVERSITY’S HUMAN RESOURCES POLICIES. PURPOSE In accordance with the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) and the State Human Resources Regulations, the University of South Carolina has established the following policy on minimum wage, the official workweek, and overtime compensation. DEFINITIONS Call Back Pay: Call back pay is pay for a non-exempt employee to report to work either before or after normal duty hours to perform emergency services. Compensatory Time: Leave time granted to an employee in lieu of overtime pay, subject to limits established in the FLSA. Exempt Employees: Employees of the University of South Carolina who are exempt from both the minimum wage and overtime requirements of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) due to employment in a bona fide executive, administrative, professional or outside sales capacity. -

Job Creation Programs of the Great Depression: the WPA and the CCC Name Redacted Specialist in Labor Economics

Job Creation Programs of the Great Depression: The WPA and the CCC name redacted Specialist in Labor Economics January 14, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R41017 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Job Creation Programs of the Great Depression: the WPA and the CCC ith the exception of the Great Depression, the recession that began in December 2007 is the nation’s most severe according to various labor market indicators. The W 7.1 million jobs cut from employer payrolls between December 2007 and September 2009, when it is thought the latest recession might have ended, is more than has been recorded for any postwar recession. Job loss was greater in a relative sense during the latest recession as well, recording a 5.1% decrease over the period.1 In addition, long-term unemployment (defined as the proportion of workers without jobs for longer than 26 weeks) was higher in September 2009—at 36%—than at any time since 1948.2 As a result, momentum has been building among some members of the public policy community to augment the job creation and worker assistance measures included in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (P.L. 111-5). In an effort to accelerate improvement in the unemployment rate and job growth during the recovery period from the latest recession,3 some policymakers recently have turned their attention to programs that temporarily created jobs for workers unemployed during the nation’s worst economic downturn—the Great Depression—with which the latest recession has been compared.4 This report first describes the social policy environment in which the 1930s job creation programs were developed and examines the reasons for their shortcomings then and as models for current- day countercyclical employment measures. -

Modern Employment Practices

Business English News 33 – Modern Employment Practices Discussion Questions 1. What is the current job situation in your country? Are there many job opportunities? 2. What advice would you give to a new graduate looking for work? 3. What solutions would you suggest for your job market to help improve it in the near future? Transcript The world quietly passed a significant milestone recently – the global jobless total surpassed 200 million people, according to a study by the UN. To put that into perspective, that’s 30 million more without work than at the height of the recession in 2008. As CBC News reports, these figures could have grave implications for the future: This is a shocker on its own, but even more ominous is the growing precariousness of the job situation for those that have them. According to the study, the overwhelming majority of people on the planet struggle with temporary work, informal or illegal jobs, long spells of unemployment and unpaid family work. In other words, most are caught in a disadvantageous spiral where exploitation is a real risk. In the UK, employers are using controversial zero-hour contracts which stipulate that workers must be available for work but have no guaranteed paid hours each week. As one union leader puts it, economic recovery is at risk if the current trends continue: We cannot build a secure recovery off the back of zero-hour contracts and weaker employment rights. If we don’t create more decent jobs, inequality will continue to soar and the economy risks running out of steam. -

Unemployment Insurance and Macroeconomic Stabilization

153 Unemployment Insurance and Macroeconomic Stabilization Gabriel Chodorow-Reich, Harvard University and the National Bureau of Economic Research John Coglianese, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Abstract Unemployment insurance (UI) provides an important cushion for workers who lose their jobs. In addition, UI may act as a macroeconomic stabilizer during recessions. This chapter examines UI’s macroeconomic stabilization role, considering both the regular UI program which provides benefits to short-term unemployed workers as well as automatic and emergency extensions of benefits that cover long-term unemployed workers. We make a number of analytic points concerning the macroeconomic stabilization role of UI. First, recipiency rates in the regular UI program are quite low. Second, the automatic component of benefit extensions, Extended Benefits (EB), has played almost no role historically in providing timely, countercyclical stimulus while emergency programs are subject to implementation lags. Additionally, except during an exceptionally high and sustained period of unemployment, large UI extensions have limited scope to act as macroeconomic stabilizers even if they were made automatic because relatively few individuals reach long-term unemployment. Finally, the output effects from increasing the benefit amount for short-term unemployed are constrained by estimated consumption responses of below 1. We propose five changes to the UI system that would increase UI benefits during recessions and improve the macroeconomic stabilization role: (I) Expand eligibility and encourage take-up of regular UI benefits. (II) Make EB fully federally financed. (III) Remove look-back provisions from EB triggers that make automatic extensions turn off during periods of prolonged unemployment. (IV) Add additional automatic extensions to increase benefits during periods of extremely high unemployment. -

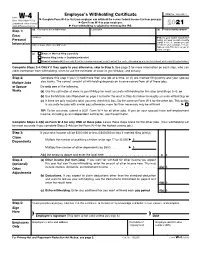

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

The Future of the Minimum Wage: the Employer Perspective

The future of the minimum wage The employer perspective Becca Gooch, Joe Dromey and David Southgate August 2020 Learning and Work Institute Patron: HRH The Princess Royal | Chief Executive: Stephen Evans A company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales Registration No. 2603322 Registered Charity No. 1002775 Registered office: 4th Floor Arnhem House, 31 Waterloo Way, Leicester LE1 6LP Published by National Learning and Work Institute 4th Floor Arnhem House, 31 Waterloo Way, Leicester LE1 6LP Company registration no. 2603322 | Charity registration no. 1002775 www.learningandwork.org.uk @LearnWorkUK @LearnWorkCymru (Wales) All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without the written permission of the publishers, save in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. 2 About Learning and Work Institute Learning and Work Institute is an independent policy, research and development organisation dedicated to lifelong learning, full employment and inclusion. We research what works, develop new ways of thinking and implement new approaches. Working with partners, we transform people’s experiences of learning and employment. What we do benefits individuals, families, communities and the wider economy. Stay informed. Be involved. Keep engaged. Sign up to become a Learning and Work Institute supporter: www.learningandwork.org.uk/supporters Acknowledgements The future of the minimum wage project is supported by the Carnegie UK Trust. We would like to thank the Carnegie UK Trust for making this work possible, and Douglas White and Gail Irvine in particular for their support.