Amicus Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paid Advertisement 50 U.S

PAID ADVERTISEMENT 50 U.S. GOVERNORS UNITE TO SUPPORT ISRAEL, FIGHT BDS We, all 50 governors across “Israel is a robust democracy with many rights and the United States and the freedoms that do not exist in neighboring countries— mayor of the District of or in much of the world. Yet, while fundamental rights Columbia, affirm: are trampled and atrocities are committed routinely not far beyond its borders, BDS supporters focus only “The goals of the BDS on Israel.” (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) movement are “The BDS movement would also undermine peace- antithetical to our values and the making by suggesting that economic and political values of our respective states.” pressure on Israel can replace real negotiation.” “We support Israel as a vital U.S. ally, important “Our commitment is to the principle of two states for economic partner and champion of freedom.” two peoples, existing side by side in peace, security and mutual recognition, and achieved through direct, “The BDS movement’s single-minded focus on the bilateral negotiations.” Jewish State raises serious questions about its motivations and intentions.” ALABAMA ILLINOIS MONTANA RHODE ISLAND KAY IVEY BRUCE RAUNER STEVE BULLOCK GINA RAIMONDO ALASKA INDIANA NEBRASKA SOUTH CAROLINA BILL WALKER ERIC HOLCOMB PETE RICKETTS HENRY MCMASTER ARIZONA IOWA NEVADA SOUTH DAKOTA DOUGLAS A. DUCEY KIM REYNOLDS BRIAN SANDOVAL DENNIS DAUGAARD ARKANSAS KANSAS NEW HAMPSHIRE TENNESSEE ASA HUTCHINSON SAM BROWNBACK CHRISTOPHER T. SUNUNU BILL HASLAM CALIFORNIA KENTUCKY NEW JERSEY TEXAS JERRY BROWN MATT BEVIN CHRIS CHRISTIE GREG ABBOTT (CO-CHAIR) COLORADO LOUISIANA NEW MEXICO JOHN HICKENLOOPER JOHN BEL EDWARDS SUSANA MARTINEZ UTAH GARY R. -

North Carolina Alabama California Georgia Iowa

NORTH CAROLINA ALABAMA CALIFORNIA GEORGIA IOWA ILLINOIS MISSOURI NEBRASKA SOUTH CAROLINA WISCONSIN May 7, 2019 The Honorable Donald J. Trump President of the United States The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Mitch McConnell Speaker of the House Senate Majority Leader The Honorable Kevin McCarthy The Honorable Charles Schumer House Minority Leader Senate Minority Leader The Honorable Nita Lowey The Honorable Richard Shelby Chair Chairman The Honorable Kay Granger The Honorable Patrick Leahy Ranking Member Ranking Member Committee on Appropriations Committee on Appropriations United States House of Representatives Unites States Senate Dear President Trump and Congressional Leadership: We write to request your urgent attention to finalizing pending FY19 Supplemental Disaster Appropriations that will provide urgently needed support for response, recovery, and long-term resilience to Americans in all States and Territories of the United States suffering the continuing effects of multiple and diverse Federally-declared disasters. We appreciate that preliminary disaster packages have advanced in both chambers. These are indeed encouraging signs, but after months of debate and continuing significant events driving widespread unmet needs for these states and communities even higher, now is the time to bring these efforts together in a final form and to bring national resources to bear where needed. Historic levels of destruction in the Caribbean, the Atlantic southeast, the Gulf coast, California, the Midwest, and even in the Pacific islands have left significant needs in their wakes impacting homeowners, farmers, our military, and Americans from all walks of life and in all parts of our far-flung nation. It is incumbent upon our national leadership to finalize a robust, timely, and fair package of assistance. -

Governors' Top Education Priorities in 2020 State of the State Addresses

MAR 2020 Governors’ Top Education Priorities in 2020 State of the State Addresses Bryan Kelley and Erin Whinnery 1 ecs.org | @EdCommission ecs.orgnga.org | | @NatlGovsAssoc@EdCommission nga.org | @NatlGovsAssoc In laying out policy priorities in their 2020 We are committed to go the distance State of the State addresses, governors recognized the role the public education because we know our children’s future system plays in supporting strong is at risk. Education is the foundation economies. Often citing the need to align of our economy and our quality of life. education with the 21st century’s knowledge Everything, including our future, begins economy, governors agreed that a high- with how well we educate our children. quality education is the key to both an individual’s and the state’s success. Alabama And that is significantly affected by the Gov. Kay Ivey echoed the sentiments of kind of beginnings we provide for them. many governors when she said, “For us to We cannot let them down. prepare today’s students for tomorrow’s Gov. David Ige opportunities, it is time we get serious.” HAWAII Each year, Education Commission of the States tracks, analyzes and identifies trends in education policy accomplishments and proposals featured in governors’ State of the State addresses. To date, 43 governors have delivered their 2020 address. The top education priorities across the states and territories span the entire education spectrum, pre-K through the workforce. Governors in at least* 34 states emphasized the importance of K-12 CAREER AND TECHNICAL EDUCATION (CTE) and WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS. Governors in at least 30 states mentioned K-12 SCHOOL FINANCE, including NEW INVESTMENTS for certain STUDENT POPULATIONS. -

PCPC Letter to Governors Regarding

Hon. Kay Ivey Hon. Mike Dunleavy Hon. Doug Ducey Governor Governor Governor State of Alabama State of Alaska State of Arizona Hon. Asa Hutchinson Hon. Gavin Newsom Hon. Jared Polis Governor Governor Governor State of Arkansas State of California State of Colorado Hon. Ned Lamont Hon. John Carney Hon. Ron DeSantis Governor Governor Governor State of Connecticut State of Delaware State of Florida Hon. Brian Kemp Hon. David Ige Hon. Brad Little Governor Governor Governor State of Georgia State of Hawaii State of Idaho Hon. JB Pritzker Hon. Eric Holcomb Hon. Kim Reynolds Governor Governor Governor State of Illinois State of Indiana State of Iowa Hon. Laura Kelly Hon. Andy Beshear Hon. John Bel Edwards Governor Governor Governor State of Kansas Commonwealth of Kentucky State of Louisiana Hon. Janet Mills Hon. Larry Hogan Hon. Charlie Baker Governor Governor Governor State of Maine State of Maryland Commonwealth of Massachusetts Hon. Gretchen Whitmer Hon. Tim Walz Hon. Tate Reeves Governor Governor Governor State of Michigan State of Minnesota State of Mississippi Hon. Mike Parson Hon. Steve Bullock Hon. Pete Ricketts Governor Governor Governor State of Missouri State of Montana State of Nebraska Hon. Steve Sisolak Hon. Chris Sununu Hon. Phil Murphy Governor Governor Governor State of Nevada State of New Hampshire State of New Jersey Personal Care Products Council 1620 L Street, NW Suite 1200 Washington, DC 20036 March 19, 2020 Page 2 of 3 Hon. Michelle Lujan Grisham Hon. Andrew Cuomo Hon. Roy Cooper Governor Governor Governor State of New Mexico State of New York State of North Carolina Hon. Doug Burgum Hon. -

Norfolk Southern Corporation Contributions

NORFOLK SOUTHERN CORPORATION CONTRIBUTIONS TO CANDIDATES AND POLITICAL COMMITTEES JANUARY 1 ‐ DECEMBER 31, 2018* STATE RECIPIENT OF CORPORATE POLITICAL FUNDS AMOUNT DATE ELECTION OFFICE OR COMMITTEE TYPE IN Eric Holcomb $1,000 01/18/2018 Primary 2018 Governor US National Governors Association $30,000 01/31/2018 N/A 2018 Association Conf. Acct. SC South Carolina House Republican Caucus $3,500 02/14/2018 N/A 2018 State Party Cmte SC South Carolina Republican Party (State Acct) $1,000 02/14/2018 N/A 2018 State Party Cmte SC Senate Republican Caucus Admin Fund $3,500 02/14/2018 N/A 2018 State Party Non‐Fed Admin Acct SC Alan Wilson $500 02/14/2018 Primary 2018 State Att. General SC Lawrence K. Grooms $1,000 03/19/2018 Primary 2020 State Senate US Democratic Governors Association (DGA) $10,000 03/19/2018 N/A 2018 Association US Republican Governors Association (RGA) $10,000 03/19/2018 N/A 2018 Association GA Kevin Tanner $1,000 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State House GA David Ralston $1,000 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State House IN Ryan Hatfield $750 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State House IN Gregory Steuerwald $500 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State House IN Karen Tallian $750 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State Senate IN Blake Doriot $750 04/16/2018 Primary 2020 State Senate IN Dan Patrick Forestal $750 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State House GA Bill Werkheiser $400 04/26/2018 Primary 2018 State House GA Deborah Silcox $400 04/26/2018 Primary 2018 State House GA Frank Ginn $500 04/26/2018 Primary 2018 State Senate GA John LaHood $500 04/26/2018 Primary 2018 State -

Medicaid Expansion Decisions by State

Medicaid Expansion Decisions by State (Last updated October 2020) State Adopted Governor Governor’s party Legislative majority’s expansion party Alabama No Kay Ivey Republican Republican Alaska Yes Mike Dunleavy Republican Republican Arizona Yes* Doug Ducey Republican Republican Arkansas Yes* Asa Hutchinson Republican Republican California Yes Gavin Newsom Democratic Democratic Colorado Yes Jared Polis Democratic Democratic Connecticut Yes Ned Lamont Democratic Democratic Delaware Yes John Carney Democratic Democratic District of Columbia Yes Muriel Bowser (Mayor) Democratic Democratic Florida No Ron DeSantis Republican Republican Georgia No Brian Kemp Republican Republican Hawaii Yes David Ige Democratic Democratic Idaho Yes Brad Little Republican Republican Illinois Yes JB Pritzker Democratic Democratic Indiana Yes* Eric Holcomb Republican Republican Iowa Yes* Kim Reynolds Republican Republican Kansas No Laura Kelly Democratic Republican Kentucky Yes Andy Beshear Democratic Republican Louisiana Yes John Bel Edwards Democratic Republican Maine Yes Janet Mills Democratic Democratic Maryland Yes Larry Hogan Republican Democratic Massachusetts Yes Charlie Baker Republican Democratic Michigan Yes* Gretchen Whitmer Democratic Republican Minnesota Yes Tim Walz Democratic Split Mississippi No Tate Reeves Republican Republican Missouri No1 Mike Parson Republican Republican Montana Yes* Steve Bullock Democratic Republican Nebraska Yes Pete Ricketts Republican Non-partisan Nevada Yes Steve Sisolak Democratic Democratic New Hampshire Yes* Chris -

August 18, 2021 the Honorable Henry Mcmaster the Honorable

THE SECRETARY OF EDUCATION WASHINGTON, DC 20202 August 18, 2021 The Honorable Henry McMaster The Honorable Molly Spearman Governor State Superintendent of Education The Capitol South Carolina Department of Education 1100 Gervais Street 1006 Rutledge Building, 1429 Senate St. Columbia, SC 29201 Columbia, SC 29201 Dear Governor McMaster and Superintendent Spearman: As the new school year begins in school districts across South Carolina, it is our shared priority that students return to in-person instruction safely. The safe return to in-person instruction requires that school districts be able to protect the health and safety of students and educators, and that families have confidence that their schools are doing everything possible to keep students healthy. South Carolina’s actions to block school districts from voluntarily adopting science-based strategies for preventing the spread of COVID-19 that are aligned with the guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) puts these goals at risk and may infringe upon a school district’s authority to adopt policies to protect students and educators as they develop their safe return to in-person instruction plans required by Federal law. We are aware that South Carolina has enacted a State law prohibiting local educational agencies (LEAs) from adopting requirements for the universal wearing of masks.1 This State level action against science-based strategies for preventing the spread of COVID-19 appears to restrict the development of local health and safety policies and is at odds with the school district planning process embodied in the U.S. Department of Education’s (Department’s) interim final requirements. -

Norfolk Southern Corporation Contributions

NORFOLK SOUTHERN CORPORATION CONTRIBUTIONS TO CANDIDATES AND POLITICAL COMMITTEES JANUARY 1 ‐ JUNE 30, 2021* STATE RECIPIENT OF CORPORATE POLITICAL FUNDS AMOUNT DATE ELECTION OFFICE OR COMMITTEE NY Dave McDonough$ 750 02/08/2021 Primary 2022 State House NY Patrick M. Gallivan$ 750 02/08/2021 Primary 2022 State Senate NY Joe Griffo$ 750 02/08/2021 Primary 2022 State Senate NY Donna Lupardo$ 750 02/08/2021 Primary 2022 State House NY Bill Magnarelli$ 1,000 02/08/2021 Primary 2022 State House NY Timothy Kennedy$ 1,000 02/08/2021 Primary 2022 State Senate US National Governors Assn. Center for Best Practices$ 30,000 02/08/2021 N/A 2021 Association LA Greg Miller $ 250 03/11/2021 Primary 2023 State House LA Phillip Tarver $ 250 03/11/2021 Primary 2023 State House LA Stephanie Hilferty$ 250 03/11/2021 Primary 2023 State House LA Matthew Willard$ 250 03/11/2021 Primary 2023 State House LA Mark Wright$ 250 03/11/2021 Primary 2023 State House LA Dewith Carrier $ 250 03/11/2021 Primary 2023 State House LA Edmond Jordan $ 250 03/11/2021 Primary 2023 State House LA Wayne McMahen$ 250 03/11/2021 Primary 2023 State House LA Paul Hollis$ 250 03/11/2021 Primary 2023 State House LA Mandie Landry$ 250 03/11/2021 Primary 2023 State House LA Patrick McMath$ 500 03/11/2021 Primary 2023 State Senate LA Gary Smith $ 500 03/11/2021 Primary 2023 State Senate LA Tanner Magee $ 500 03/11/2021 Primary 2023 State House LA Patrick Connick$ 500 03/11/2021 Primary 2023 State Senate LA Beth Mizell$ 500 03/11/2021 Primary 2023 State Senate US Democratic Governors Association -

Governor Scorecards

Voice for Refuge Governor Scorecards June 2021 Score Ranking Governor Name State Party Pro-Refugee Champion, Pro-Refugee Supporter, Out of 15 Uncommitted, Anti-Refugee Extremist Kay Ivey Alabama R 0 Uncommitted Mike Dunleavy Alaska R 6 Refugee Supporter Doug Ducey Arizona R 5.5 Refugee Supporter Asa Hutchinson Arkansas R 5 Refugee Supporter Gavin Newsom California D 15 Pro-Refugee Champion Jared Polis Colorado D 13 Pro-Refugee Champion Ned Lamont Connecticut D 11.5 Pro-Refugee Champion John Carney Delaware D 6.5 Refugee Supporter Ron DeSantis Florida R -3 Anti-Refugee Extremist Brian Kemp Georgia R 2 Uncommitted David Ige Hawaii D 8.5 Refugee Supporter Brad Little Idaho R 5 Refugee Supporter J. B. Pritzker Illinois D 13 Pro-Refugee Champion Eric Holcomb Indiana R 5 Refugee Supporter Kim Reynolds Iowa R 4 Uncommitted Laura Kelly Kansas D 5.5 Refugee Supporter Andy Beshear Kentucky D 5 Refugee Supporter John Bel Edwards Louisiana D 4.5 Refugee Supporter Janet Mills Maine D 7.5 Refugee Supporter Larry Hogan Maryland R 4.5 Refugee Supporter Charlie Baker Massachusetts R 7.5 Refugee Supporter Gretchen Whitmer Michigan D 13.5 Pro-Refugee Champion Tim Walz Minnesota D 12 Pro-Refugee Champion Tate Reeves Mississippi R -0.5 Anti-Refugee Extremist Mike Parson Missouri R 9 Refugee Supporter Greg Gianforte Montana R 3.5 Uncommitted Pete Ricketts Nebraska R 0 Uncommitted Steve Sisolak Nevada D 11 Pro-Refugee Champion Chris Sununu New Hampshire R 6 Refugee Supporter Phil Murphy New Jersey D 13.5 Pro-Refugee Champion Michelle Lujan Grisham New Mexico -

Governors' Chiefs of Staff and Schedulers

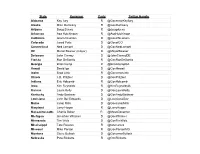

Updated 10/10/18 Governors’ Chiefs of Staff and Schedulers State Governor Contact Phone Number Alabama Kay Ivey (R) Chief of Staff: Steve Pelham 334-242-7100 Alabama Kay Ivey (R) Scheduler: Andrea Medders 334-242-7151 Alaska Bill Walker (I) Chief of Staff: Scott Kendall 907-465-3500 Alaska Bill Walker (I) Scheduler: Janice Mason 907-465-3500 Arizona Doug Ducey (R) Chief of Staff: Kirk Adams 602-542-4331 Arizona Doug Ducey (R) Scheduler: Cassie Wicklund 602-542-4331 Arkansas Asa Hutchinson (R) Chief of Staff: Alison Williams 501-682-2345 Arkansas Asa Hutchinson (R) Scheduler: Jennifer Bruce 501-682-2345 California Jerry Brown (D) Chief of Staff: Diana Dooley 916-445-2841 California Jerry Brown (D) Scheduler: Kathy Baldree 916-324-7745 Colorado John Hickenlooper (D) Chief of Staff: Patrick Meyers 303-866-2471 Colorado John Hickenlooper (D) Scheduler: Ali Murray 303-866-2471 Connecticut Dan Malloy (D) Chief of Staff: Brian Durand 800-406-1527 Connecticut Dan Malloy (D) Scheduler: Lady Mendoza 800-406-1527 Delaware John Carney (D) Chief of Staff: Doug Gramiak 302-744-4101 Delaware John Carney (D) Scheduler: Tara Mazer 302-744-4101 Florida Rick Scott (R) Chief of Staff: Brad Piepenbrink 850-488-7146 Florida Rick Scott (R) Scheduler: Diane Moulton 850-488-7146 Georgia Nathan Deal (R) Chief of Staff: Chris Riley 404-656-1776 Georgia Nathan Deal (R) Scheduler: Courtney Brown 404-656-1776 Hawaii David Ige (D) Chief of Staff: Mike McCartney 808-586-0034 Hawaii David Ige (D) Scheduler: Joyce Kami 808-568-0034 Idaho C.L. -

Governor's Twitter Handles- 2020

State Governor Party Twitter Handle Alabama Kay Ivey R @GovernorKayIvey Alaska Mike Dunleavy R @GovDunleavy Arizona Doug Ducey R @dougducey Arkansas Asa Hutchinson R @AsaHutchinson California Gavin Newsom D @GavinNewsom Colorado Jared Polis D @GovofCO Connecticut Ned Lamont D @GovNedLamont DC Muriel Bowser (mayor) D @MayorBowser Delaware John Carney D @JohnCarneyDE Florida Ron DeSantis R @GovRonDeSantis Georgia Brian Kemp R @BrianKempGA Hawaii David Ige D @GovHawaii Idaho Brad Little R @GovernorLittle Illinois J.B. Pritzker D @GovPritzker Indiana Eric Holcomb R @GovHolcomb Iowa Kim Reynolds R @KimReynoldsIA Kansas Laura Kelly D @GovLauraKelly Kentucky Andy Beshear D @GovAndyBeshear Louisiana John Bel Edwards D @LouisianaGov Maine Janet Mills D @GovJanetMills Maryland Larry Hogan R @LarryHogan Massachussetts Charlie Baker R @MassGovernor Michigan Gretchen Whitmer D @GovWhitmer Minnesota Tim Walz D @GovTimWalz Mississippi Tate Reeves R @tatereeves Missouri Mike Parson R @GovParsonMO Montana Steve Bullock D @GovernorBullock Nebraska Pete Ricketts R @GovRicketts Nevada Steve Sisolak D @SteveSisolak New Hampshire Chris Sununu R @GovChrisSununu New Jersey Phil Murphy D @GovMurphy New Mexico Michelle Lujan Grisham D @GovMLG New York Andrew Cuomo D @NYGovCuomo North Carolina Roy Cooper D @NC_Governor North Dakota Doug Burgum R @DougBurgum Ohio Mike DeWine R @GovMikeDeWine Oklahoma Kevin Stitt R @GovStitt Oregon Kate Brown D @OregonGovBrown Pennsylvania Tom Wolf D @GovernorTomWolf Puerto Rico Wanda Vazquez Garced NPP @wandavazquezg Rhode Island Gina Raimondo D @GinaRaimondo South Carolina Henry McMaster R @henrymcmaster South Dakota Kristi Noem R @govkristinoem Tennessee Bill Lee R @GovBillLee Texas Greg Abbott R @GregAbbott_TX Utah Gary Herbert R @GovHerbert Vermont Phil Scott R @GovPhilScott Virginia Ralph Northam D @GovernorVA Washington Jay Inslee D @GovInslee West Virginia Jim Justice R @WVGovernor Wisconsin Tony Evers D @GovEvers Wyoming Mark Gordon R @GovernorGordon. -

February 26, 2021 the President the White

February 26, 2021 The President The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20500 Dear Mr. President: We the undersigned Governors write to express our concerns over the ongoing crisis involving a global shortage of auto-grade semiconductor wafers, which is already having a harmful impact on the U.S. automotive industry and its workers by forcing plant closures and production volume reductions in several of our states. It is our understanding that your Administration has already engaged relevant government and industry officials in markets where most of the auto-grade semiconductor wafers are produced, and we thank you for those efforts. However, in light of the growing list of automakers, suppliers, and dealers negatively affected by the shortage, we ask you to redouble those efforts. The automotive industry is heavily reliant on semiconductors given their use in vehicle safety, control, emissions, and driver information systems. Amid the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak, semiconductor wafer production was diverted, leading to the current shortage facing the automotive sector. Unfortunately, when automotive assembly and auto parts production ramped-up after North American auto facilities reopened in May, auto-grade wafer production was not restored to pre-pandemic levels. We know of other foreign governments that continue to urge wafer and semiconductor companies to expand production capacity and/or temporarily reallocate a modest portion of their current production to auto-grade wafer production. We respectfully request that the Biden Administration do the same by continuing the drumbeat on behalf of automakers in the U.S. and their workers until there is a sufficient semiconductor supply to meet the strong demand for our vehicles, which has been one of the bright spots in our recovering economy.