The Impact of Comedy on Racial and Ethnic Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation

Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation SCOPE The Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation sector (sector 71) includes a wide range of establish- ments that operate facilities or provide services to meet varied cultural, entertainment, and recre- ational interests of their patrons. This sector comprises (1) establishments that are involved in producing, promoting, or participating in live performances, events, or exhibits intended for pub- lic viewing; (2) establishments that preserve and exhibit objects and sites of historical, cultural, or educational interest; and (3) establishments that operate facilities or provide services that enable patrons to participate in recreational activities or pursue amusement, hobby, and leisure time interests. Some establishments that provide cultural, entertainment, or recreational facilities and services are classified in other sectors. Excluded from this sector are: (1) establishments that provide both accommodations and recreational facilities, such as hunting and fishing camps and resort and casino hotels are classified in Subsector 721, Accommodation; (2) restaurants and night clubs that provide live entertainment, in addition to the sale of food and beverages are classified in Subsec- tor 722, Food Services and Drinking Places; (3) motion picture theaters, libraries and archives, and publishers of newspapers, magazines, books, periodicals, and computer software are classified in Sector 51, Information; and (4) establishments using transportation equipment to provide recre- ational and entertainment services, such as those operating sightseeing buses, dinner cruises, or helicopter rides are classified in Subsector 487, Scenic and Sightseeing Transportation. Data for this sector are shown for establishments of firms subject to federal income tax, and sepa- rately, of firms that are exempt from federal income tax under provisions of the Internal Revenue Code. -

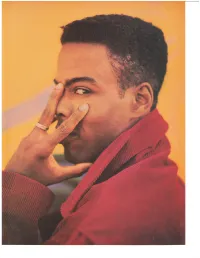

Chris Rock? by Tom 0'Lleill Spot in the Lineup)Than Performing Themundane Task of Pr0motings0me Moviehe's Only Co-Written, Coproduced Andstarred In

ook'$ toll ChrisRock's eyes dart toward the door of hisoffice every time thesound of hiscolleague$ at work 0n the other side nearly knocksit off its hinges. Clearly, he'd rather be ouer there with Adam$andler, David $pade and Chris Farley - theYoung Turks of '$aturdayl{ight [ive' - whippingupa sketch for this week's show (anden$uring his Firstthe comedy clubs, then the almighty 'Saturdayl{ight live' and noltr his otlln movie, nCB4.n Dogood thingscome in threes for Chris Rock? By Tom 0'lleill spot in the lineup)than performing themundane task of pr0motings0me moviehe's only co-written, coproduced andstarred in. Perched notunlike abird about to take flight, the twenty-six-year-old sits onthe heels of hisshoe$, planted $quarely onthe seat of his swivelchair, and turns in measured half-circles. "The pres$ure's 0il,"says Fock of 'C84'(short for "Cell Block 4") the rap c0me- dythat could propel him out of herefaster than you can think tddief$urphy."l||y namens allover this. lf it hits,we got a hit. lf it fails,'Cilristoek'is the only name the audience isgoing t0 krow.nn Photog/aphs by D OMINIQUE PALOMBO US APRIL 1993.69 f Heaps of paper literally falling from his desktop every time he "But no one took me seriously becauseI was too young." brushes against it testify that it's not for lack of trying that this At about the sametime, Grazer met rap pioneer Tone Loc and whisper-thin comedian (five-foot-eleven, 130 pounds) isn't becamefascinated with what he perceivedto be a subculture of akeady a household name. -

Kelly Carlin to Host New Show on Siriusxm

Kelly Carlin to Host New Show on SiriusXM "The Kelly Carlin Show," the new monthly show on Raw Dog Comedy and Carlin's Corner channels to launch with special guest Robin Williams NEW YORK, Feb. 9, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- Sirius XM Radio (NASDAQ: SIRI) announced today that Kelly Carlin, daughter of George Carlin, one of the most influential comedians of all time, will host a new monthly show on Raw Dog Comedy, channel 99, and on Carlin's Corner, the new 24/7 channel devoted to George Carlin, channel 400. (Logo: http://photos.prnewswire.com/prnh/20101014/NY82093LOGO ) Each month, The Kelly Carlin Show will feature Kelly interviewing a different comedian, stand-up comedy, personal stories and memories about her legendary and beloved father. The monthly show will kick off with a revealing conversation with special guest Robin Williams, during which the two will discuss Williams' experience on The Richard Pryor Show and Mork & Mindy, what it takes to be an actor versus a stand-up comedian and Williams' thoughts on the end of the world. The Kelly Carlin Show will premiere on Sunday, February 12 at 7:00 pm ET and will air the first Sunday of every month on Raw Dog Comedy, channel 99. The Kelly Carlin Show will also air the first Monday of every month at 8:00 pm ET on Carlin's Corner, channel 400. Upcoming episodes are scheduled to feature conversations with special guests Eddie Izzard, Lewis Black and Chris Hardwick. SiriusXM Raw Dog Comedy features uncensored comedy from the edge: classic comedy, the hottest new stand-ups and original shows. -

Download Press Release As PDF File

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS - PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS ANNOUNCES PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN Emmy, Grammy and Academy Award Winning Hollywood Legend’s Trademark White Suit Costume, Iconic Arrow through the Head Piece, 1976 Gibson Flying V “Toot Uncommons” Electric Guitar, Props and Costumes from Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, Little Shop of Horrors and More to Dazzle the Auction Stage at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills All of Steve Martin’s Proceeds of the Auction to be Donated to BenefitThe Motion Picture Home in Honor of Roddy McDowall SATURDAY, JULY 18, 2020 Los Angeles, California – (June 23rd, 2020) – Julien’s Auctions, the world-record breaking auction house to the stars, has announced PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN, an exclusive auction event celebrating the distinguished career of the legendary American actor, comedian, writer, playwright, producer, musician, and composer, taking place Saturday, July 18th, 2020 at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills and live online at juliensauctions.com. It was also announced today that all of Steve Martin’s proceeds he receives from the auction will be donated by him to benefit The Motion Picture Home in honor of Roddy McDowall, the late legendary stage, film and television actor and philanthropist for the Motion Picture & Television Fund’s Country House and Hospital. MPTF supports working and retired members of the entertainment community with a safety net of health and social -

George Lopez Show Youtube

George lopez show youtube "What am I gonna tell my mom? She thinks I'm at Epcot!!" Bruh I relate, told my parents I was stayin the. In the hilarious third season of George Lopez, George's life hasn't become Bullock (the show's co. Funny Parts From 2 George Lopez Episodes. This is my show I watch it every morning when I wake up for. George Lopez Season 1 Outtakes. no1banonna. Loading. I miss this show but it is on at 3 in the morning I. George Lopez Why You Crying Show more with all these celebrities dying and even though George isnt. funniest George Lopez quotes ever. your mother, ta loco I enjoyed meeting your mother" DUDE IM DEAD. The Martin Show Bloopers - Duration: JJMAX , views · Lopez Tonight - Interview. belita and george works well together. i tried watching the saint george and that mom he has on there. george lopez full episodes. Show more. Show less. Loading Autoplay When autoplay is enabled, a. SAINT GEORGE premieres MARCH 6th at 9pm on FX! Funniest Comedy Show Best Stand up Comedy Apollo needs to boot Steve Harvey as replace him with George instead!!!. Read more. Show Lopez is so. Vic is hilarious and his relationship with George is the BEST. Enjoy! Copyright The George Lopez Show. All. Mix - Hilarious George Lopez SceneYouTube · George Mesmerizing - Duration: Sarmen 15, George Lopez spanglish very funny lol. Show more. Show less George Lopez one of the best latino. George Lopez S04E14 George Gets Assisterance Part 3 HQ. jeff sa George Lopez Season 4. -

Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment CURRENT ISSUES in ISLAM

Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment CURRENT ISSUES IN ISLAM Editiorial Board Baderin, Mashood, SOAS, University of London Fadil, Nadia, KU Leuven Goddeeris, Idesbald, KU Leuven Hashemi, Nader, University of Denver Leman, Johan, GCIS, emeritus, KU Leuven Nicaise, Ides, KU Leuven Pang, Ching Lin, University of Antwerp and KU Leuven Platti, Emilio, emeritus, KU Leuven Tayob, Abdulkader, University of Cape Town Stallaert, Christiane, University of Antwerp and KU Leuven Toğuşlu, Erkan, GCIS, KU Leuven Zemni, Sami, Universiteit Gent Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment Settling into Mainstream Culture in the 21st Century Benjamin Nickl Leuven University Press Published with the support of the Popular Culture Association of Australia and New Zealand University of Sydney and KU Leuven Fund for Fair Open Access Published in 2020 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). © Benjamin Nickl, 2020 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Non-Derivative 4.0 Licence. The licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non- commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: B. Nickl. 2019. Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment: Settling into Mainstream Culture in the 21st Century. Leuven, Leuven University Press. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Further details about Creative Commons licences -

31St ANNUAL WOMEN of ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS GALA to HONOR

Contact: Vivacity Media Group | 212-812-1483 Leslie Papa, [email protected] Whitney Holden Gore, [email protected] Ailsa Hoke, [email protected] WOMEN’S PROJECT THEATER PRESENTS THE 31st ANNUAL WOMEN OF ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS GALA TO HONOR Emmy Award-winning Stage, Screen, and TV Actress & Founder of A Is For.. MARTHA PLIMPTON Celebrated Film, Television and Theater Producer, President of Segal NYC and Gatherer Entertainment JENNA SEGAL Award-Winning Actress, Film Producer, and Director & Founder of The Rainforest Fund TRUDIE STYLER HOSTED BY Celebrated comedienne, Two-time Grammy Nominee & Comedy Central Roast Star LISA LAMPANELLI WITH SPECIAL PERFORMANCES & APPEARANCES BY Fun Home’s Tony Award Nominee & Tony Award Winner BETH MALONE & JEANINE TESORI Acclaimed Dance Company MONICA BILL BARNES & CO. Emmy Award Nominated creator of “Call The Midwife” HEIDI THOMAS AND MORE SOON TO BE ANNOUNCED MONDAY, JUNE 13, 2016 AT THE EDISON BALLROOM, NYC TICKETS AVAILABLE VIA WPTHEATER.ORG (New York, NY) Women’s Project Theater (WP Theater), under the leadership of Producing Artistic Director Lisa McNulty and Managing Director Maureen Moynihan, is thrilled to announce the 31st ANNUAL WOMEN OF ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS GALA. The gala will honor Emmy Award winning actress Martha Plimpton; celebrated film, television and Broadway producer Jenna Segal; and actress, producer, environmentalist and UNICEF ambassador Trudie Styler. Hosted by Grammy nominated comedienne Lisa Lampanelli, with special performances by Fun Home’s Tony Award Nominee Beth Malone and Tony Award winner Jeanine Tesori; dance company Monica Bill Barnes & Co. and a presentation by Emmy Award nominee Heidi Thomas (creator of “Call the Midwife”), the Gala will take place on Monday, June 13, 2016 at 6:30pm at The Edison Ballroom, 240 W 47th Street. -

COMEDY CENTRAL Records(R) to Release George Lopez's 'Tall, Dark & Chicano' CD on Tuesday, December 15

COMEDY CENTRAL Records(R) to Release George Lopez's 'Tall, Dark & Chicano' CD on Tuesday, December 15 NEW YORK, Nov 23, 2009 -- He has his own nightly talk show, a hit comedy series and now this! George Lopez adds another notch to his belt with his new COMEDY CENTRAL Records CD, "Tall, Dark & Chicano" released on Tuesday, December 15. George Lopez's "Tall, Dark & Chicano" CD is a recording of his live stand-up HBO special, where he performed in front of a packed arena crowd at the AT&T Center in San Antonio, TX. One of the most popular comedic actors in the world, Lopez's standup comedy is a sell-out attraction from coast to coast. Well- known as the co-creator, writer, producer, and star of the hit sitcom "George Lopez," Lopez has hosted the Latin Emmy® Awards, co-hosted the Emmys® and now has his own nightly comedy talk show on TBS. He's also a celebrated radio show host in his hometown of Los Angeles, as well as a writer, and comedy recording artist, with CDs and DVDs selling in excess of six figures. Previously released recordings by COMEDY CENTRAL Records include: Greg Giraldo's "Midlife Vices, Nick Swardson's "Seriously, Who Farted?," Doug Benson's "Unbalanced Load," Dane Cook's "ISolated INcident," Cook's platinum-selling "Harmful If Swallowed" and double-platinum "Retaliation," Mitch Hedberg's "Do You Believe in Gosh?," Grammy Award-winning "Lewis Black: The Carnegie Hall Performance," Grammy Award-nominees' Steven Wright's "I Still Have A Pony" and George Lopez's "America's Mexican," Joe Rogan's "Shiny Happy Jihad," Christopher Titus's "5th Annual End Of The World Tour," Norm MacDonald's "Ridiculous," Demetri Martin's "These Are Jokes," "Jim Gaffigan: Beyond The Pale," Mike Birbiglia's "My Secret Public Journal Live," D.L. -

Read Book ^ Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa / TKNZIXTAS6A9

7FDWAO06DEBA eBook \ Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa Madagascar: Escape 2 A frica Filesize: 5.28 MB Reviews Completely among the best pdf I actually have possibly read through. It is probably the most awesome pdf we have read. You wont really feel monotony at whenever you want of your time (that's what catalogs are for about in the event you ask me). (Prof. Martine Lesch) DISCLAIMER | DMCA QO2SVENHMT8D < Doc ^ Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa MADAGASCAR: ESCAPE 2 AFRICA To get Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa PDF, make sure you click the button under and save the ebook or have access to other information that are in conjuction with MADAGASCAR: ESCAPE 2 AFRICA book. Alphascript Publishing Feb 2010, 2010. Taschenbuch. Condition: Neu. Neuware - Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa is a 2008 sequel to the 2005 film Madagascar, about the continuing adventures of Alex the Lion, Marty the Zebra, Melman the Girae, and Gloria the Hippo. It is directed by Eric Darnell and written by Etan Cohen. It stars the voices of Ben Stiller, Chris Rock, David Schwimmer, Jada Pinkett Smith, Sacha Baron Cohen, Cedric the Entertainer, and Andy Richter. Also providing voices are Bernie Mac, Alec Baldwin, Sherri Shepherd and will.i.am. It was produced by DreamWorks Animation and distributed by Paramount Pictures, and was released on November 7, 2008. The film starts as a prequel, showing a small part of Alex's early life, including his capture by hunters. It soon moves to shortly aer the point where the original le o, with the animals deciding to return to New York. They board an airplane in Madagascar, but crash- land in Africa, where each of the central characters meets others of the same species; Alex is reunited with his parents. -

Occupy Bellingham's Winter Woes

STINKY STORIES, P.6 * RAPTOR RAPTURE, P.12 * ANCHOR ART, P.16 cascadia REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA WHATCOM*SKAGIT*ISLAND*LOWER B.C. 01.04.12::#01::V.07::FREE FilmsBest OF 2011 P. 2 2 ALL THAT JAZ: BEHIND THE SCENES AT THE IDIOM THEATER, P.15 :: MY GOODNESS: BIG SOUNDS FROM A DYNAMIC DUO, P.18 EVICTED! OCCUPY BELLINGHAM’S WINTER WOES, P.8 Whether you’re planning 31 cascadia a winter wedding or are FOOD looking ahead to a spring knot-tying, you’ll likely find 25 what you need at the $ 2 B-BOARD A glance at what’s happening this week Jan. 8 at the Best Western Lakeway Inn 22 22 FILM FILM 2 ) .4[01.{.12] ONSTAGE 18 Into the Woods Auditions: 6-9pm, Phillip Tarro Theatre, Skagit Valley College MUSIC WORDS Vincent Standley: 7pm, Village Books 16 ART ART /#0-.4[01.|.12] 15 ONSTAGE STAGE STAGE Good, Bad, Ugly: 8pm, Upfront Theatre The Project: 10pm, Upfront Theatre 14 WORDS Julie Marie Wade: 7pm, Village Books WORDS !-$4[01.}.12] 12 ONSTAGE Alice in Wonderland: 6:30pm, Bellingham Arts Academy GET OUT for Youth Umik!: 7pm, Blaine Performing Arts Center 8 Improv Evolution: 8pm, Upfront Theatre 48 Hour Theater Festival: 8pm and 10pm, iDiOM Theater Cagematch: 10pm, Upfront Theatre CURRENTS CURRENTS MUSIC 6 The Endorfins: 9pm, Old Foundry Winter Masquerade: 10pm-2am, the Majestic VIEWS VIEWS WORDS 4 Chris Linder: 7pm, Village Books MAIL MAIL GET OUT Eagle Viewing: 10am-4pm, Howard Miller Steelhead Park, 2 Rockport DO IT IT DO DO IT 2 VISUAL ARTS First Friday Gallery Walk: 6-9pm, downtown Anacortes Art Walk: 6-10pm, downtown Bellingham .12 04 ./0-4[01.~.12] .07 01. -

Walter Latham Biography

Walter Latham Often referred to as "The King of Comedy,” Walter Latham is grateful for the humble upbringing and everyday challenges that shaped his early life, and instilled in him a fierce passion that led to his success as a business mogul and humanitarian. Born to a single mother in East New York, Brooklyn, Latham soon found himself in a similar situation, becoming a father at the young age of 18, and struggling to get by with odd jobs and a brief stint in the United States Air Force. At 20, he caught a break with a permanent position at the American Express Call Center in Greensboro, NC and was thrilled to finally provide healthcare for his son, even though he knew he was bound for something greater. Inspiration soon struck Latham, after attending a performance by his childhood friend, MC Lyte, when he realized his calling was to produce concerts. He borrowed money from his mother and produced his first concert in a nightclub. The headline act didn’t show and Latham had to refund the patrons their money but what he learned from this unfortunate experience would change his path forever. Latham decided to produce more concerts but mitigate his losses by soliciting sponsorships. He wrote and mailed 50 letters to various corporations about promoting a southeast tour with the hottest comedians. When Coors Brewing Company expressed interest, Latham soon found himself, at age 21, standing in a boardroom of top executives pitching his comedy idea. His first comedy tour featured Chris Tucker and Bill Bellamy and Coors was so impressed they asked Latham to do another. -

We Ve Got Your Game

JUST FOR LAUGHS! (continued) ���������������� ���������������������� TUES., JAN. 27 - WED., JAN. 28 Finding the Funniest College Kid Robert Klein The DC Improv’s search for the District’s See the comedian who has entertained Funniest College begins its sixth season and thrilled audiences for more than 40 later this month. The Improv will host free years and has been nominated twice for comedy showcases at most of the major Best Comedy Album of the Year at the universities in the area from January Grammys for “Child of the Fifties” and to March featuring college comedians “Mind over Matter.” Currently preparing entertaining the audiences with five his eighth HBO one-man show, Klein can minutes of original material. Judges will be seen regularly on television thanks choose two students from each college to his more than 100 appearances on to compete in the finals at the DC Improv “The Tonight Show” and “Late Night on March 25. The winner gets a paid with David Letterman.” Don’t miss this hosting gig at the DC Improv, among other New Yorker as he comes to DC Improv accolades. American University kicks off for just two nights. Shows on both days the competition on Jan. 21. Georgetown start at 8:30 p.m. and tickets are $20. University, University of Maryland, George DC Improv: 1140 Connecticut Ave. NW, Mason University and George Washington Washington, D.C. 202-296-7008. www. University also are participating. See the dcimprov.com full schedule here at www.dcimprov.com. — Kristina Hernandez THURS., JAN. 29 - SAT., JAN. 31 The DC Improv Comedy Club: 1140 Dennis Regan Connecticut Ave.