Exposing for RAW - Digital Photo Pro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intro to Digital Photography.Pdf

ABSTRACT Learn and master the basic features of your camera to gain better control of your photos. Individualized chapters on each of the cameras basic functions as well as cheat sheets you can download and print for use while shooting. Neuberger, Lawrence INTRO TO DGMA 3303 Digital Photography DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY Mastering the Basics Table of Contents Camera Controls ............................................................................................................................. 7 Camera Controls ......................................................................................................................... 7 Image Sensor .............................................................................................................................. 8 Camera Lens .............................................................................................................................. 8 Camera Modes ............................................................................................................................ 9 Built-in Flash ............................................................................................................................. 11 Viewing System ........................................................................................................................ 11 Image File Formats ....................................................................................................................... 13 File Compression ...................................................................................................................... -

Optimum Exposure but Think About This for a Moment. Who Gets to Say

Optimum exposure But think about this for a moment. Who gets to say whether a given exposure is correct or not? I don’t like using the word correct in relation to exposure because it implies that there is only one right answer. I prefer the term ‘optimum exposure’. This is the exposure setting that is best suited to the scene that you are photographing and the medium you are using. Imagine that you are photographing the same subject with four different cameras. One is loaded with black and white film, another with colour transparency film, the third with colour negative film and the last is a digital camera. Each has the same lens and frames the subject the same way. The quantity of light falling on the subject is also the same. Potentially, the scene could require four different exposure settings. That’s because each camera is using a different medium which reacts to light in a slightly different way. Film users will know that black and white film, slide film and colour negative film all need to be treated differently. The same goes for digital cameras. Put simply, the optimum exposure depends as much on the medium you are using as the quantity of light falling on the subject. That’s another reason why cameras get exposure wrong. The metering system has yet to be invented that takes into account the medium being used as well as the amount of light entering the lens. JPEG vs. RAW Even with digital cameras, the optimum exposure may be different depending on whether you are using the JPEG or Raw format. -

Nature Photography Articles? Send Them to the Editor

Front Page | Articles | Galleries | Forums | Portfolios | Gear Shoppe | Links | Membership Shoot It RAW! Text and photography copyright © Nick Rains. All rights reserved. A RAW file is like raw sugar - it is unprocessed (and sweet!). Untouched, basic, linear digital information uninterpreted by software. Not very useful as it is but, more importantly, not locked into any file format or colour balance that might restrict its future use. Some people call a RAW file a 'digital negative' but it is considerably more than that. A RAW file is a 'latent image' and is much more like an exposed but unprocessed B+W negative, as we'll see in a moment. Now, bear with me a moment whilst I set the scene by very briefly looking at how good old film works. Film Both traditional film and digital sensors in dSLRs capture light in a single exposure but the way they do this is quite different. Sensitised transparency materials consist of an essentially random distribution of 'grains' which are chemically processed to reveal the dye couplers in different layers of the film. All films have slightly different responses to colours - Kodak films are often more neutral and Fuji films are more saturated and brighter. Light is actually recorded in 3 different layers, each one dedicated to a particular range of wavelengths of light. Colour film can actually be thought of as 3 layers of B+W film with one of the 3 different primary additive colour dyes in each layer. Exposure to light chemically transforms the light sensitive grains into a latent image proportionate to the intensity of the light. -

Side 6-22. Del 2. Efterbehandling Af Billeder Taget I Svagt Lys – Side 23-32

Vs.2 af Allan Kierulff Indledning: side 2-5 Del 1: Fototeknikkens udstyr og basis regler – side 6-22. Del 2. Efterbehandling af billeder taget i svagt lys – side 23-32. https://fotografering.allan-kierulff.dk/ BILLEDET ER TAGET MED: ISO 100, -2EV, F8 4 SEK. NEDENFOR: ISO 3200, F2.8, 1/30 SEK. 1 Når lyset tager af, ændrer selv de mest velkendte scener sig, hvilket skaber en mulighed for helt anderledes billeder. Natoptagelse kræver lange eksponeringer for at sikre, at svage lysniveauer optages på sensoren. DSLR kameraet giver mulighed for at eksponerer i op til 30 sekunder, men der kan være tidspunkter, hvor der er brug for længere lukkertider for at optage virkelig mørke scener som eks. vis. måne-belyste landskaber. Kameraet skal stilles i funktionen ”Bulb”. Ved hjælp af kameraets ”Bulb” funktion kan lukkeren holdes åben så længe det skal være, hvilket giver lyset mere tid til at registrer billedt på kortet. Lav-lys fotografering er ikke nødvendigvis bare natfotografering, som mange mennesker antager. Det kan være forskellige lys-mængder fra forskellige kilder, og hvad der er svagere end lys i dagtimerne, anser jeg for svage lys. I denne artikel vil jeg udelukkende holde mig til fotografering udendørs. Tre niveauer af svagt lys. Før vi går videre, lad os først definere de forskellige niveauer af svagt lys og kategorisere dem, så så begreberne er på plads. 1. Synlig til svagt: i dagslys ved tilfældige skyggeområder - bag bygninger, under store træer eller broer o.l. 2. Svagt til lavt lys: Efter eller lige omkring solnedgang, når det stadig er klart nok til at se alt omkring sig, eller når man er indendørs. -

The Snapshot

A Newsletter of the Redwood Camera Club THE SNAPSHOT July and August 2016 SOME SUMMER SIXTEEN It may be hard to believe, but this year brings us the 8th annual Humboldt Photography Exhibition. Eight years! Five of the seven grand prize winners have been RCC members. Entry day is July 16th at the RAA, 609 F Street, from 11AM to 2PM. Complete details should have been emailed to all RCC members. If you didn’t get this email, please contact Sharon Falk-Carlsen. This IN THIS ISSUE year the Eureka Chamber of Commerce has chosen to focus on the RAA for the month of August. Some Summer ‘16 ..................... 1 This entails a cocktail event to be held at the RAA building (while the HPE in on exhibit) on August Kathryn Mayo Samples .......... 2 18th from 5PM-7PM. Everyone is invited! And besides this, the HPE is a wonderful photography Maxing Dynamic Range ......... 3 competition and exhibition. Part One: Alfred Stieglitz ..... 4-5 The judge this year is Kathryn Mayo, who heads the photography program at Consumnes River College Freshwater Farms Trail ........ 6-7 in Sacramento, where since 2007 she has been teaching Exploring Bald Hills ................ 8 photography full-time and where she has served as chair Flowers by Pam ....................... 9 of her department. She teaches a broad range of classes in Shore Acres ............................. 10 both film and digital, encompassing all film formats from Classifieds & Notices .............. 10 35mm to large and ultra large format, photo history, photo manipulation, and alternative photographic processes. She Board Members ...................... 10 also teaches private workshops at her home studio in the wet Annual Picnic Info ................ -

Art & Still Life

Art & Still Life OnlineOnline Issue 8 Michael Hall Pimp my Pic Shooting a long-term documentary project Glenn Edwards Johnathan Journalism Report Thompson Food Styling Image of the Blast From Month The Past Jonny Seymour Bryn Create Stunning Black Griffiths and White Portraits Contrived Spontaneity Michelle Whitmore Instagram Featured Photographer WALL PRODUCTS CONTENTS BASICS WITH BRIAN 4 - 10 UNDERSTANDING THE HISTOGRAM IMAGE OF THE MONTH 12 - 14 BLACK AND WHITE PORTRAITS 16 - 21 JONNY SEYMOUR FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER 24 - 36 MICHELLE WHITMORE WELCOME TO THE BIG PHOTO ACADEMY LIVE CRIT TOP TEN 38 - 50 E-ZINE THE PHOTOGRAPHER ACADEMY This month we’ve decided to let our arty side PIMP MY PIC 52 - 53 out and contemplate the world of Still life and THE SYSTEM 54 - 73 Art photography. Photographer Academy ELINCHROM Master Michelle Whitmore lets us in on what drives her to keep experimenting, and Michael SHOOTING A LONG-TERM 74 - 90 DOCUMENTARY PROJECT Hall shares his passion and techniques that MICHAEL HALL have been the core of his long-term climate 92 - 93 change project. We also have the usual great BLAST FROM THE PAST selection of hints, tips and insights to help you POSING THE BRIDE take your photography to that next level. WHY YOU SHOULD PRINT YOUR 96 - 100 The Big Photo is, as ever, designed as a PHOTOGRAPHS LISA BEANEY celebration of photography, so expect the usual array of great images and useful tips ANTICIPATION OF COMPOSITION 102 - 103 on how you can improve you own images MARK SEYMOUR across a range of photographic subjects. CONTRIVED SPONTANEITY 104 - 108 And if you’re looking for something we BRYN GRIFFTHS Razor-sharp focus on your photography haven’t covered here, don’t forget that The Photographer Academy has a huge FEATURED STUDIO 110 - 121 Create high resolution wall art with metal or acrylic catalogue of films covering all sorts of CHRYSALIS photography. -

Fundamentals of Photography PHTC 1311 2017

Southwest College Course Syllabus PHTC 1311 Fundamentals of Photography CRN 34407 – Fall 2017 Alief – Hayes Campus- Room B319 | 6:00 pm –9:50 pm | Tue Instructor: Terry Halsey Instructor Contact Information: Office: 832.248.6892 | Email: [email protected] Office location and hours: I do not have an office on campus Please feel free to contact me concerning any problems that you are experiencing in this course. You do not need to wait until you have received a poor grade before asking for my assistance. Your performance in my class is very important to me. I am available to hear your concerns and just to discuss course topics. Feel free to come by my office anytime during these hours. Course Description An introduction to digital camera operation, image production, composition, supplemental lighting, and use of exposure meters and filters. Prerequisites Prerequisites Lead 1370 Total Course Hours Credit and Lecture - 96.00; External Hours: 48 hours Note: One hour of classroom instruction equates to a minimum of 1.5 hours of out-of-class student work for each week. External hours of student work may include assignments, projects, research, exam certification practice, and/or field trips. Example: 2 lecture, 4 lab hours Lecture 2hrs x 16 weeks = 32 hrs Lab hours 4hrs x 16 weeks = 64 hrs External Hours 3hrs x 16 weeks = 48 hrs TOTAL hours = 144 hours Instructional Materials Required: A Short Course in Photography [Barbara London, Jim Stone ISBN: 978-0-205-99825-8) Supplemental: Adobe Lightroom and Photoshop for Photographers ISBN: 978-0-13-381671-6 Equipment needed for class 1. -

Louis Benjamin. the Naked and the Lens

THE NAKED AND THE LENS A GUIDE FOR NUDE PHOTOGRAPHY Louis Benjamin This page intentionally left blank THE NAKED AND THE LENS A GUIDE FOR NUDE PHOTOGRAPHY Louis Benjamin AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK Copyright © 2010, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science & Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (+44) 1865 843830, fax: (+44) 1865 853333, E-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage (http://elsevier.com), by selecting “Support & Contact” then “Copyright and Permission” and then “Obtaining Permissions.” Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Application submitted British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 978-0-240-81159-8 For information on all Focal Press publications visit our website at www.elsevierdirect.com Typeset by: diacriTech, Chennai, India 10 11 12 13 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in Canada Dedication To Denise, with more love than you can imagine. You always inspire me, and any magic in these pages comes from you. -

Photographic Noise Performance Measures Based on RAW Files Analysis of Consumer Cameras

Article Photographic Noise Performance Measures Based on RAW Files Analysis of Consumer Cameras Jorge Igual Instituto de Telecomunicaciones y Aplicaciones Multimedia (ITEAM), Departamento de Comunicaciones, Universitat Politècnica de València, 46022 Valencia, Spain; [email protected]; Tel.: +34-96-6528515 Received: 30 September 2019; Accepted: 31 October 2019; Published: 4 November 2019 Abstract: Photography is being benefited from the huge improvement in CMOS image sensors. New cameras extend the dynamic range allowing photographers to take photos with a higher quality than they could imagine one decade ago. However, the existence of different technologies make more complicated the photographic analysis of how to determine the optimal camera exposure settings. In this paper, we analyze how the different noise models are translated to different signal to noise SNR curve patterns and which factors are relevant. In particular, we discuss profoundly the relationships between exposure settings (shutter speed, aperture and ISO). Since a fair comparison between cameras can be tricky because of different pixel size, sensor format or ISO scale definition, we explain how the pixel analysis of a camera can be translated to a more helpful universal photographic noise measure based on human perception and common photography rules. We analyze the RAW files of different camera models and show how the noise performance analysis (SNR and dynamic range) interact with photographer’s requirements. Keywords: photography; CMOS image sensor; noise; signal to noise ratio; dynamic range 1. Introduction Photography has experienced two revolutions in this century so far: the technological one, where digital cameras have replaced film cameras (the substitution was completed in 2008 [1]), and the social one, where cameras in mobile phones, the Internet and social media are changing the use and meaning of photography beyond the traditional one (i.e., to capture life moments) [2], making photography more popular, cheaper, easier, faster and less skill demanding. -

Winter - 2021 Volume 4 Issue 1

Winter - 2021 Volume 4 Issue 1 The Seven Ponds Photography Club, formed in 2009, was created to promote the advancement of photography as an art. The purpose of the club is to bring together persons of like mind who are dedicated to the advancement of their skills by association with other members, through the study of the work of others and through spirited and friendly competition. The club exists to offer opportunities for all to share knowledge within the club and in the community, through exhibitions and programs that excite interest in the knowledge and practice of all branches of photography. Sutherland Nature Sanctuary Valentine’s SPPC Members, Weekend Group Outing Contributor – Tina Daniels, photos by Kristin Due to the growing concerns over the Grudzien COVID-19/Coronavirus, and the decision of Seven Ponds Nature Center to close for group meetings for everyone's well On Feb. 13, 2021 we had our being, the Seven Ponds Photo Club Board of Directors has decided it is in the first Seven Ponds Photograph best interest of our club members and Club Valentine’s Day any visitors to cancel our upcoming in- Scavenger hunt at Sutherland person meetings: Nature Sanctuary. The scavenger hunt was spread We are sorry for any inconvenience and out over 1.2 miles that traversed different hope that you and your family stay landscape topography in the area. Each trail- head healthy and safe. was marked by large multi-colored hearts, to Jim Lewis ensure participants knew which trail to explore. The weather was a balmy 20 degrees and there SPPC President was soft snow falling that morning. -

The Practical Zone System, Fourth Edition

JohnsonChapt_Prelims.qxd 8/4/06 6:53 PM Page i THE PRACTICAL ZONE SYSTEM This page intentionally left blank JohnsonChapt_Prelims.qxd 8/4/06 6:53 PM Page iii THE PRACTICAL ZONE SYSTEM for Film and Digital Photography Fourth Edition A Simple Guide to Photographic Control CHRIS JOHNSON Amsterdam • Boston • Heidelberg • London New York • Oxford • Paris • San Diego San Francisco • Singapore • Sydney • Tokyo Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier JohnsonChapt_Prelims.qxd 8/4/06 6:53 PM Page iv Acquisitions Editor: Diane Heppner Project Manager: Paul Gottehrer Assistant Editor: Stephanie Barrett Marketing Manager: Christine Degon Veroulis Cover Design: Alisa Andreola Interior Design: Alisa Andreola Typesetter: Charon Tec Ltd (A Macmillan Company), Chennai, India; www.charontec.com Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK Copyright © 2007, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science & Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (ϩ44) 1865 843830, fax: (ϩ44) 1865 853333, E-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage (http://elsevier.com), by selecting “Support & Contact” then “Copyright and Permission” and then “Obtaining Permissions.” Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, Elsevier prints its books on acid-free paper whenever possible. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Application submitted British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

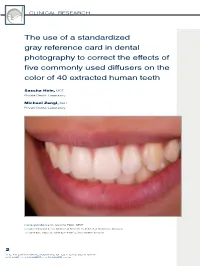

The Use of a Standardized Gray Reference Card in Dental Photography to Correct the Effects of Five Commonly Used Diffusers on the Color of 40 Extracted Human Teeth

HEIN/ZANGL CLINICAL RESEARCH CLINICAL RESEARCH The use of a standardized gray reference card in dental photography to correct the effects of five commonly used diffusers on the color of 40 extracted human teeth Sascha Hein, MDT Private Dental Laboratory Michael Zangl, MDT Private Dental Laboratory Correspondence to: Sascha Hein, MDT Dentaltechnik Christ & Hein GmbH, Karl-Benz-Str. 25, 86825 Bad Wörishofen, Germany. Tel.: 0049 8247 5320 Fax.: 0049 8247 31965; E-mail: [email protected] 2 THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ESTHETIC DENTISTRY VOLUME 11 • NUMBER 2 • SUMMER 2016 HEIN/ZANGL Abstract ter software (Ricci Adams, version 1.6 (122)) was used to obtain CIE L*a*b* Objective: The aim of this in vitro study values of the specimens before and af- was to investigate the color changes of ter white balancing and exposure cor- human teeth caused by five different dif- rection. fuser materials commonly used in dental Results: All diffusers caused visually photography, as well as software influ- perceivable color changes on the ex- ence, and to confirm whether the use tracted teeth: White Frost (∆E* 1.24; of a standardized gray reference card sd 0.47), 80 gsm printing paper is effective in correcting these color (∆E* 2.94; sd 0.35), LumiQuest polyam- changes during digital postproduction. ide (∆E* 3.68; sd 0.54), PET (∆E* 6.55; Materials and method: Forty extracted sd 0.41), and 3M linear polarizing fil- human teeth were obtained from a spe- ter sheet (∆E* 7.58; sd 1.00). The use cialized oral surgery practice in Cham, of a standardized gray reference card Germany.