978–0–230–31384–2 Copyrighted Material – 978–0–230–31384–2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neues Textdokument (2).Txt

Filmliste Liste de filme DVD Münchhaldenstrasse 10, Postfach 919, 8034 Zürich Tel: 044/ 422 38 33, Fax: 044/ 422 37 93 www.praesens.com, [email protected] Filmnr Original Titel Regie 20001 A TIME TO KILL Joel Schumacher 20002 JUMANJI 20003 LEGENDS OF THE FALL Edward Zwick 20004 MARS ATTACKS! Tim Burton 20005 MAVERICK Richard Donner 20006 OUTBREAK Wolfgang Petersen 20007 BATMAN & ROBIN Joel Schumacher 20008 CONTACT Robert Zemeckis 20009 BODYGUARD Mick Jackson 20010 COP LAND James Mangold 20011 PELICAN BRIEF,THE Alan J.Pakula 20012 KLIENT, DER Joel Schumacher 20013 ADDICTED TO LOVE Griffin Dunne 20014 ARMAGEDDON Michael Bay 20015 SPACE JAM Joe Pytka 20016 CONAIR Simon West 20017 HORSE WHISPERER,THE Robert Redford 20018 LETHAL WEAPON 4 Richard Donner 20019 LION KING 2 20020 ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW Jim Sharman 20021 X‐FILES 20022 GATTACA Andrew Niccol 20023 STARSHIP TROOPERS Paul Verhoeven 20024 YOU'VE GOT MAIL Nora Ephron 20025 NET,THE Irwin Winkler 20026 RED CORNER Jon Avnet 20027 WILD WILD WEST Barry Sonnenfeld 20028 EYES WIDE SHUT Stanley Kubrick 20029 ENEMY OF THE STATE Tony Scott 20030 LIAR,LIAR/Der Dummschwätzer Tom Shadyac 20031 MATRIX Wachowski Brothers 20032 AUF DER FLUCHT Andrew Davis 20033 TRUMAN SHOW, THE Peter Weir 20034 IRON GIANT,THE 20035 OUT OF SIGHT Steven Soderbergh 20036 SOMETHING ABOUT MARY Bobby &Peter Farrelly 20037 TITANIC James Cameron 20038 RUNAWAY BRIDE Garry Marshall 20039 NOTTING HILL Roger Michell 20040 TWISTER Jan DeBont 20041 PATCH ADAMS Tom Shadyac 20042 PLEASANTVILLE Gary Ross 20043 FIGHT CLUB, THE David -

A Paula Ortiz Film Based on “Blood Wedding”

A Paula Ortiz Film A PAULA ORTIZ FILM INMA ÁLEX ASIER CUESTA GARCÍA ETXEANDÍA Based on “Blood Wedding” from Federico García Lorca. A film produced by GET IN THE PICTURE PRODUCTIONS and co-produced by MANTAR FILM - CINE CHROMATIX - REC FILMS BASED ON BLOOD WEDDING THE BRIDE FROM FEDERICO GARCÍA LORCA and I follow you through the air, like a straw lost in the wind. SYNOPSIS THE BRIDE - Based on “Blood Wedding” from F. García Lorca - Dirty hands tear the earth. A woman’s mouth shivers out of control. She breathes heavily, as if she were about to choke... We hear her cry, swallow, groan... Her eyes are flooded with tears. Her hands full with dry soil. There’s barely nothing left of her white dress made out of organza and tulle. It’s full of black mud and blood. Staring into the dis- tance, it’s dicult for her to breathe. Her lifeless face, dirtied with mud, soil, blood... she can’t stop crying. Although she tries to calm herself the crying is stronger, deeper. THE BRIDE, alone underneath a dried tree in the middle of a swamp, screams out loud, torn, endless... comfortless. LEONARDO, THE GROOM and THE BRIDE, play together. Three kids in a forest at the banks of a river. The three form an inseparable triangle. However LEONARDO and THE BRIDE share an invisible string, ferocious, unbreakable... THE GROOM looks at them... Years have gone by, and THE BRIDE is getting ready for her wedding. She’s unhappy. Doubt and anxiety consume her. She lives in the middle of white dessert lands, barren, in her father’s house with a glass forge. -

KEROUAC, JACK, 1922-1969. John Sampas Collection of Jack Kerouac Material, Circa 1900-2005

KEROUAC, JACK, 1922-1969. John Sampas collection of Jack Kerouac material, circa 1900-2005 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Kerouac, Jack, 1922-1969. Title: John Sampas collection of Jack Kerouac material, circa 1900-2005 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1343 Extent: 2 linear feet (4 boxes) and 1 oversized papers box (OP) Abstract: Material collected by John Sampas relating to Jack Kerouac and including correspondence, photographs, and manuscripts. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Related Materials in Other Repositories Jack Kerouac papers, New York Public Library Related Materials in This Repository Jack Kerouac collection and Jack and Stella Sampas Kerouac papers Source Purchase, 2015 Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. John Sampas collection of Jack Kerouac material, circa 1900-2005 Manuscript Collection No. 1343 Citation [after identification of item(s)], John Sampas collection of Jack Kerouac material, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. -

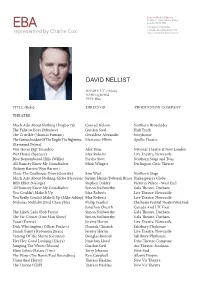

David Nellist

Eamonn Bedford Agency 1st Floor - 28 Mortimer Street London W1W 7RD EBA t +44(0) 20 7734 9632 e [email protected] represented by Charlie Cox www.eamonnbedford.agency DAVID NELLIST HEIGHT: 5’5” (165cm) HAIR: Light/Mid EYES: Blue TITLE (Role) DIRECTOR PRODUCTION COMPANY THEATRE Much Ado About Nothing (Dogberry) Conrad Nelson Northern Broadsides The Fulstow Boys (Maurice) Gordon Steel Hull Truck The Crucible (Thomas Putnam) Geraldine Alexander Storyhouse The Curious Incident Of The Dog In The Nighttime Marianne Elliott Apollo Theatre (Reverend Peters) War Horse (Sgt Thunder) Alex Sims National Theatre at New London Wet House (Spencer) Max Roberts Live Theatre, Newcastle Blue Remembered Hills (Willie) Psyche Stott Northern Stage and Tour Alf Ramsey Knew My Grandfather Mark Wingett Darlington Civic Theatre (Sidney Barron/Wyn Barron) Close The Coalhouse Door (Geordie) Sam West Northern Stage Much Ado About Nothing/Globe Mysteries Jeremy Herrin/Deborah Bruce Shakespeare’s Globe Billy Elliot (George) Stephen Daldry Victoria Palace - West End Alf Ramsey Knew My Grandfather Simon Stallworthy Gala Theatre, Durham You Couldn’t Make It Up Max Roberts Live Theatre, Newcastle You Really Coudn’t Make It Up (Mike Ashley) Max Roberts Live Theatre, Newcastle Nicholas Nickleby (Ned Cheeryble) Philip Franks/ Chichester Festival Theatre/West End Jonathan Church Canada And UK Tour The Likely Lads (Bob Ferris) Simon Stallworthy Gala Theatre, Durham The Far Corner (One Man Show) Simon Stallworthy Gala Theatre, Durham Toast (Dezzie) Jeremy Herrin Live Theatre, -

False Authenticity in the Films of Woody Allen

False Authenticity in the Films of Woody Allen by Nicholas Vick November, 2012 Director of Thesis: Amanda Klein Major Department: English Woody Allen is an auteur who is deeply concerned with the visual presentation of his cityscapes. However, each city that Allen films is presented in such a glamorous light that the depiction of the cities is falsely authentic. That is, Allen's cityscapes are actually unrealistic recreations based on his nostalgia or stilted view of the city's culture. Allen's treatment of each city is similar to each other in that he strives to create a cinematic postcard for the viewer. However, differing themes and characteristics emerge to define Allen's optimistic visual approach. Allen's hometown of Manhattan is a place where artists, intellectuals, and writers can thrive. Paris denotes a sense of nostalgia and questions the power behind it. Allen's London is primarily concerned with class and the social imperative. Finally, Barcelona is a haven for physicality, bravado, and sex but also uncertainty for American travelers. Despite being in these picturesque and dynamic locations, happiness is rarely achieved for Allen's characters. So, regardless of Allen's dreamy and romanticized visual treatment of cityscapes and culture, Allen is a director who operates in a continuous state of contradiction because of the emotional unrest his characters suffer. False Authenticity in the Films of Woody Allen A Thesis Presented To the Faculty of the Department of English East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MA English by Nicholas Vick November, 2012 © Nicholas Vick, 2012 False Authenticity in the Films of Woody Allen by Nicholas Vick APPROVED BY: DIRECTOR OF DISSERTATION/THESIS: _______________________________________________________ Dr. -

The Secret Scripture

Presents THE SECRET SCRIPTURE Directed by JIM SHERIDAN/ In cinemas 7 December 2017 Starring ROONEY MARA, VANESSA REDGRAVE, JACK REYNOR, THEO JAMES and ERIC BANA PUBLICITY REQUESTS: Transmission Films / Amy Burgess / +61 2 8333 9000 / [email protected] IMAGES High res images and poster available to download via the DOWNLOAD MEDIA tab at: http://www.transmissionfilms.com.au/films/the-secret-scripture Distributed in Australia by Transmission Films Ingenious Senior Film Fund Voltage Pictures and Ferndale Films present with the participation of Bord Scannán na hÉireann/ the Irish Film Board A Noel Pearson production A Jim Sheridan film Rooney Mara Vanessa Redgrave Jack Reynor Theo James and Eric Bana THE SECRET SCRIPTURE Six-time Academy Award© nominee and acclaimed writer-director Jim Sheridan returns to Irish themes and settings with The Secret Scripture, a feature film based on Sebastian Barry’s Man Booker Prize-winning novel and featuring a stellar international cast featuring Rooney Mara, Vanessa Redgrave, Jack Reynor, Theo James and Eric Bana. Centering on the reminiscences of Rose McNulty, a woman who has spent over fifty years in state institutions, The Secret Scripture is a deeply moving story of love lost and redeemed, against the backdrop of an emerging Irish state in which female sexuality and independence unsettles the colluding patriarchies of church and nationalist politics. Demonstrating Sheridan’s trademark skill with actors, his profound sense of story, and depth of feeling for Irish social history, The Secret Scripture marks a return to personal themes for the writer-director as well as a reunion with producer Noel Pearson, almost a quarter of a century after their breakout success with My Left Foot. -

What Are You If Not Beat? – an Individual, Nothing

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy “What are you if not beat? – An individual, nothing. They say to be beat is to be nothing.”1 Individual and Collective Identity in the Poetry of Allen Ginsberg Supervisor: Paper submitted in partial Dr. Sarah Posman fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels” by Sarah Devos May 2014 1 From “Variations on a Generation” by Gregory Corso 0 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Dr. Posman for keeping me motivated and for providing sources, instructive feedback and commentaries. In addition, I would like to thank my readers Lore, Mathieu and my dad for their helpful additions and my library companions and friends for their driving force. Lastly, I thank my two loving brothers and especially my dad for supporting me financially and emotionally these last four years. 1 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1. Ginsberg, Beat Generation and Community. ............................................................ 7 Internal Friction and Self-Promotion ...................................................................................... 7 Beat ......................................................................................................................................... 8 ‘Generation’ & Collective Identity ......................................................................................... 9 Ambivalence in Group Formation -

This Is Not a Dissertation: (Neo)Neo-Bohemian Connections Walter Gainor Moore Purdue University

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2015 This Is Not A Dissertation: (Neo)Neo-Bohemian Connections Walter Gainor Moore Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations Recommended Citation Moore, Walter Gainor, "This Is Not A Dissertation: (Neo)Neo-Bohemian Connections" (2015). Open Access Dissertations. 1421. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/1421 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Graduate School Form 30 Updated 1/15/2015 PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Walter Gainor Moore Entitled THIS IS NOT A DISSERTATION. (NEO)NEO-BOHEMIAN CONNECTIONS For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Is approved by the final examining committee: Lance A. Duerfahrd Chair Daniel Morris P. Ryan Schneider Rachel L. Einwohner To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Thesis/Dissertation Agreement, Publication Delay, and Certification Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 32), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy of Integrity in Research” and the use of copyright material. Approved by Major Professor(s): Lance A. Duerfahrd Approved by: Aryvon Fouche 9/19/2015 Head of the Departmental Graduate Program Date THIS IS NOT A DISSERTATION. (NEO)NEO-BOHEMIAN CONNECTIONS A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Walter Moore In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Lance, my advisor for this dissertation, for challenging me to do better; to work better—to be a stronger student. -

Roth Is Noted for Her Ability to Collaborate with Actors and Directors In

Roth is noted for her ability to collaborate with actors and directors in creating indelible characters, and has worked repeatedly with such artists as Mike Nichols, Stephen Daldry, Anthony Minghella, Meryl Streep, Jane Fonda, Robin Williams, Nicole Kidman and Daniel Day-Lewis. In addition to her four Academy Award nominations, Roth has received four Tony Award. nominations for her costume designs for the stage (most recently, for her work on The Book of Mormon) and three Emmy Award. nominations (including her work on the miniseries "Mildred Pierce"). This special event will be both a celebration of Roth's career and an examination of her work and craft, featuring film clips and in-depth discussions of her creative process. "Ann's work has helped bring some of our most iconic movie characters to life," said Academy CEO Dawn Hudson. "She's a beloved artist whose work continues to inspire all of us. " "We are honored that in our festival's anniversary year we are able to recognize and salute such an extraordinary woman as Ann Roth," said Executive Director Karen Arikian. "She epitomizes the inspirational creative talent that we have endeavored to present to our audiences at HIFF for the last 20 years." "It is, of course, a tremendous honor to be recognized for one's work by one's peers" said Ann Roth. "I gratefully thank both The Academy Of Motion Picture Arts And Sciences and The Hamptons International Film Festival and I commend the festival on its steely optimism in waiting until 2012 to bestow such an honor on me". -

Gerry Nucifora Boom Operator

Gerry Nucifora Boom Operator Agent: Top Technicians Management +61 9958 1611 E mail: [email protected] Australian Mobile: +61 417 676 516 Cellurare Italy: +39 3280162534 E mail: [email protected] Australian Resident with an Italian Passport and EEC membership Location Experience: Australia, Italia, Thailand, Kenya, England, Brazil, India, China,and Morroco Languages : English, Italian, a little Spanish 2010 The Burning Man Sound: David Lee Dir: Jonathan Teplitzky Sleeping Beauty Sound: David Lee Dir: Julia Leigh 2009 Tomorrow When the War Began Sound: David Lee Dir: Stuart Beattie A Model Daughter Sound: Chris Alderton Dir: Tony Tilse 30 Seconds Sound: Chris Alderton Dir: Shawn Seet Last Ride Sound: David Lee Dir: Glendyn Ivan 2008 Wolverine Sound: Guntis Sics Dir: Gavin Hood Australia Sound: Guntis sics Dir: Baz Luhrman (4 weeks of additional boom) 2007 Nim’s Island Sound: David Lee Dir: Jenifer Flackett & Mark Levine Il Capo Dei Capi (Italy) Sound: Massimo Simonetti Dir: Alexis Sweet 2005/06 L’Ultimo Padrino (Italy) Sound: Massimo Simonetti Dir: Marco Risi The Hills Have Eyes (Morocco) Sound: David Lee Dir: Martin Weisz & Wes Werrin L’Uomo Di Vetro (Italy) Sound: Massimo Simonetti Dir: Stefano Incerti The Painter Veil (China) Sound: David Lee Dir: John Curran Candy Sound: Mark Blackwell Dir: Neil Armfield 2003/04 Stealth (Australia & Thailand) Sound: David Lee Dir: Rob Cohen 2002 Peter Pan Sound: Ben Osmo Dir: P.J Hogan 2001/02 The Matrix 2 & 3 Sound: David Lee Dir: Andy & Larry Wachowski 2001 The Man Who Sued God Sound: -

Item List for Location ZE for the Item Groups You Selected

10:14 AM 1/24/2018 Item List for Location ZE For The Item Groups You Selected Call Number Title Author Publisher Pub. Date Barcode 613.7 Bey (VHS) Beyond basic yoga for dummies Dragonfly Productions[unknown] Inc. 33246001206861 613.7046 AM (DVD) AM PM yoga for beginners Lions Gate Entertainment,[2012] 33246002326791 941.83508 Lew Secret child : Lewis, Gordon. Harper Element, [2015] 33246002313112 (ON TRACE) BBC DVD FICMI-5, MI-5 volume (s.7) 07 BBC Video ; [2010] 33246002010338 (ON TRACE) DVD FIC Eight8 movie family adventure collection Echo Bridge Home Entertainment,[2013] 33246002290732 (ON TRACE) DVD FIC NothiNothing in common Tri Star, [2002] 33246001431956 (ON TRACE) DVD FIC RedRed Magnolia Home Entertainment,[2008] 33246002179083 (ON TRACE) DVD FIC StarStar trek XI Paramount, [2009] 33246001904911 BBC DVD FIC Above (s.2)Above suspicion, set 2 ITV Studios Home Entertainment[2012] ;33246002162659 BBC DVD FIC Agath (M. Agatha7 & 12) Christie's Marple, set 1, volume 2 : A&E Television Networks[2006] : 33246001875970 BBC DVD FIC Agath (M. Agatha8 & 9) Christie's Marple, set 1, volume 1 : A&E Television Networks[2006] : 33246001875962 BBC DVD FIC Agath (T. 2)Agatha Christie's Partners in Crime, set 2 distributed exclusively[2004]. by Acorn Media,33246002226959 BBC DVD FIC Balle Ballet shoes BFS Video, [2000] 33246001613892 BBC DVD FIC Berke Berkeley square, the complete series / BFS, [2011] 33246002256402 BBC DVD FIC Broad (s.1)Broadchurch, season 1 / Entertainment One (New[2014] Releases), 2013.33246002277978 BBC DVD FIC Broke (s. 3)The Brokenwood mysteries, series 3 Acorn, [2017] 33246002396141 BBC DVD FIC Danie Daniel Deronda BBC Video ; [2003] c2002.33246001980986 BBC DVD FIC Death (s.2)Death in paradise, season 2 BBC ; [2013] 33246002248862 BBC DVD FIC Death (s.3)Death in paradise, season 3 BBC Worldwide., [2014] 33246002356111 BBC DVD FIC Death (s.5)Death in paradise, season 5 BBC Video, [2016] 33246002313419 BBC DVD FIC Downt (DowntonDownton Abbey Abbey, s. -

Film, Philosophy Andreligion

FILM, PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION Edited by William H. U. Anderson Concordia University of Edmonton Alberta, Canada Series in Philosophy of Religion Copyright © 2022 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in Philosophy of Religion Library of Congress Control Number: 2021942573 ISBN: 978-1-64889-292-9 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image: "Rendered cinema fimstrip", iStock.com/gl0ck To all the students who have educated me throughout the years and are a constant source of inspiration. It’s like a splinter in your mind. ~ The Matrix Table of contents List of Contributors xi Acknowledgements xv Introduction xvii William H.