ARTICLES Ernest Gruening and the Tonkin Gulf Resolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Murkowski Has Fought Long, Hard Battle for Alaska

Anchorage Daily News profiles of Frank Murkowski and Fran Ulmer Page 1 2002 Alaska Governor’s Race Murkowski has fought long, hard a governor who will take them on." Murkowski said he feels an obligation to return to battle for Alaska Alaska to, as he puts it, get the state's economy moving By Liz Ruskin Anchorage Daily News (Published: again. October 27, 2002) Some of his critics say he can best help the state by staying put. But when he announced his candidacy last Washington -- Frank Murkowski is no stranger to year, Murkowski revealed he doesn't see a bright future success and good fortune. for himself in the Senate. The son of a Ketchikan banker, he grew up to He was forced out of his chairmanship of the become a banker himself and rose steadily through the powerful Senate Energy Committee when the executive ranks. Democrats took the Senate last year. Even if At 32, he became the youngest member of Gov. Republicans win back the Senate, Murkowski said, he Wally Hickel's cabinet. would have to wait at least eight years before he could He has been married for 48 years, has six grown take command of another committee. children and is, according to his annual financial "My point is, in my particular sequence of disclosures, a very wealthy man. seniority, I have no other committee that I can look He breezed through three re-elections. forward to the chairmanship (of) for some time," he But in the Senate, his road hasn't always been so said at the time. -

The Relationship Between Indigenous Rights, Citizenship, and Land in Territorial Alaska: How the Past Opened the Door to the Future

The Relationship between Indigenous Rights, Citizenship and Land in Territorial Alaska: How the Past Opened the Door to the Future Item Type Article Authors Swensen, Thomas M. Download date 02/10/2021 20:55:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/5825 Swensen The Relationship between Indigenous Rights, Citizenship, and Land GROWING OUR OWN: INDIGENOUS RESEARCH, SCHOLARS, AND EDUCATION Proceedings from the Alaska Native Studies Conference (2015) The Relationship between Indigenous Rights, Citizenship, and Land in Territorial Alaska: How the Past Opened the Door to the Future Thomas Michael Swensen1 1Ethnic Studies Department, Colorado State University, CO. On 4 March 1944 the Alaskan newspaper the Nome Nugget published an editorial written by sixteen-year-old local Inupiat Alberta Schenck. In her letter she publically voiced how many Alaska Natives felt in their homelands amid the employment of racial prejudice against them. “To whom it may concern: this is a long story but will have to make it as brief as possible,” she began, addressing the tensions “between natives, breeds, and whites.” In the editorial forum of the Nome Nugget the young Schenck implemented a discussion concerning discrimination toward Indigenous people, as made apparent in her use of racist language in distinguishing herself and members of her fellow Indigenous community as “natives” and “breeds.”1 An unexpected activist, Schenck worked as an usher at the Alaska Dream Theater in Nome where she took tickets and assisted patrons in locating their seats. At her job she was also responsible for maintaining the lines of segregation between seating for White patrons on the main floor and Native patrons in the balcony. -

Diapering the Devil: How Alaska Helped Staunch Befouling by Mismanaged Oil Wealth: a Lesson for Other Oil Rich Nations JAY HAMMOND

02-933286-70-9 CH 2:0559-8 10/4/12 11:37 AM Page 5 2 Diapering the Devil: How Alaska Helped Staunch Befouling by Mismanaged Oil Wealth: A Lesson for Other Oil Rich Nations JAY HAMMOND Preface “I call petroleum the devil’s excrement. It brings trouble. Look at this locura—waste, corruption, consumption, our public services falling apart. And debt, debt we shall have for years.” So warned Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonso, a Venezuelan founder of OPEC. A September 24, 2004, article in the British magazine The Economist elaborates further on Pérez Alfonso: During the heady oil boom of the mid-1970s . he was seen as an alarmist. In fact, he was astonishingly prescient. Oil producers vastly expanded domestic spending, mostly on gold- plated infrastructure projects that set inflation roaring and left mountains of debt. Worse, this did little for the poor. Venezuela had earned over $600 billion in oil revenues since the mid- 1970s but the real income per person of Pérez Alfonso’s compatriots fell by 15% in the decade after he expressed his disgust. The picture is similar in many OPEC countries. So bloated were their budgets that when oil prices fell to around Editor’s note: This chapter has kept as much as possible Hammond’s original text even though it was an unfinished manuscript. 5 02-933286-70-9 CH 2:0559-8 10/4/12 11:37 AM Page 6 6 Jay Hammond Acknowledgments from Larry Smith, coordinator The Hammond Family: Bella Gardiner Hammond, Jay’s wife, who keeps the home fires burning and who asked her granddaughter, Lauren Stanford, to send me the author's last draft. -

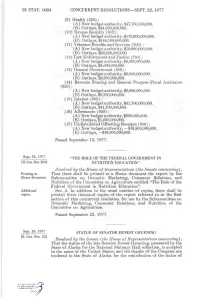

91 Stat. 1684 Concurrent Resolutions—Sept

91 STAT. 1684 CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS—SEPT. 22, 1977 (9) Health (550) : (A) New budget authority, $47,700,000,000. (B) Outlays, $44,200,000,000. (10) Income Security (600) : (A) New budget authority, $178,600,000,000. (B) Outlays, $146,100,000,000. (11) Veterans Benefits and Services (700) ; (A) New budget authority. $19,900,000,000. (B) Outlays, $20,200,000,000. (12) Law Enforcement and Justice (750) : (A) New budget authority, $3,800,000,000. (B) Outlays, $4,000,000,000. (13) General Government (800) : ' ' . (A) New budget authority, $3,800,000,000. (B) Outlays, $3,850,000,000. (14) Revenue Sharing and General Purpose Fiscal Assistance (850) : (A) New budget authority, $9,600,000,000. (B) Outlays, $9,700,000,000. (15) Interest (900) : (A) New budget authority, $41,700,000,000. (B) Outlays, $41,700,000,000. (16) Allowances (920) : (A) New budget authority, $900,000,000. (B) Outlays, $1,000,000,000. (17) Undistributed Offsetting Receipts (950) : ' ' (A) New budget authority, - $16,800,000,000. (B) Outlays, -$16,800,000,000. Passed September 15, 1977. Sept. 22, 1977 "THE ROLE OF THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT IN [H. Con. Res. 263] NUTRITION EDUCATION" Resolved hy the Rouse of Representatives {the Senate concurring)^ Printing as That there shall be- printed as a House document the report by the House document. Subcommittee on Domestic Marketing, Consumer Relations, and Nutrition of the Committee on Agriculture entitled "The Role of the Federal Government in Nutrition Education". Additional SEC. 2. In addition to the usual number of copies, there shall be copies. -

Congressional Record—Senate S1045

February 25, 2014 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S1045 After statehood, Governor Stepovich the same year a group of Alaska Na- began their public pursuit of equal turned his attention to representing tives from Southeast formed the Alas- rights for all people in Alaska. Alaska in the U.S. Senate. He lost his ka Native Brotherhood to advocate for Elizabeth began to call upon her bid in 1958 to be one of Alaska’s first a right to U.S. citizenship for Alaska friends and family to involve them- Senators to Ernest Gruening, who had Natives. In 1915, Alaska Native women selves in the anti-discrimination move- served in Washington as one of Alas- came together and established the ment. She recruited women to meet ka’s fir two ‘‘shadow’’ Senators since Alaska Native Sisterhood to work with a Senator from Nome in order to 1956. Stepovich later ran and lost races alongside the brotherhood. Although express to him what it felt like to be to be Governor, first against William Elizabeth was very young for the cre- discriminated against, left out of the A. Egan and later against Walter ation of these bodies, each came to United Service Organization, and Hickel. But his defeats did not dimin- play a great role in her fight for equal forced to read signs in local businesses ish his interest in or dedication to rights. barring them from entry. Elizabeth and Alaska. And he remained especially Many Americans are familiar with Roy met with Governor Gruening to committed to Fairbanks and the rest of the history of discrimination and pres- strategize their movement, and then the Interior region. -

Mike Gravel, Unconventional Two-Term Alaska Senator,

Mike Gravel, Unconventional Two-Term Alaska Senator, ... https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/27/us/politics/mike-gr... https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/27/us/politics/mike-gravel-dead.html Mike Gravel, Unconventional Two-Term Alaska Senator, Dies at 91 He made headlines by fighting for an oil pipeline and reading the Pentagon Papers aloud. After 25 years of obscurity, he re-emerged with a quixotic presidential campaign. By Adam Clymer June 27, 2021 Updated 9:47 a.m. ET Mike Gravel, a two-term Democratic senator from Alaska who played a central role in 1970s legislation to build the Trans-Alaska oil pipeline but who was perhaps better known as an unabashed attention-getter, in one case reading the Pentagon Papers aloud at a hearing at a time when newspapers were barred from publishing them and later mounting long-shot presidential runs, died on Saturday at his home in Seaside, Calif. He was 91. The cause was myeloma, his daughter, Lynne Mosier, said. Defeated in his bid for a third Senate term in 1980, Mr. Gravel remained out of the national spotlight for 25 years before returning to politics to seek the 2008 Democratic presidential nomination. He was a quirky fixture in several early debates in 2007, calling for a constitutional amendment to allow citizens to enact laws by referendums. But when the voting began in 2008, he never got 1 percent of the total in any primary. He nonetheless persisted, showing the same commitment to going it alone that he had displayed by nominating himself for vice president in 1972, staging one-man filibusters and reading the Pentagon Papers aloud — efforts that even senators who agreed with him regarded as grandstanding. -

Black History in the Last Frontier

Black History in the Last History Black Frontier Black History Black History in the Last Frontier provides a chronologically written narrative to encompass the history of African Americans in in the Last Frontier Alaska. Following an evocative foreword from activist and community organizer, Ed Wesley, the book begins with a discussion of black involvement in the Paciÿc whaling industry during the middle and late-nineteenth century. It then discusses how the Gold Rush and the World Wars shaped Alaska and brought thousands of black migrants to the territory. °e ÿnal chapters analyze black history in Alaska in our contemporary era. It also presents a series of biographical sketches of notable black men and women who passed through or settled in Alaska and contributed to its politics, culture, and social life. °is book highlights the achievements and contributions of Alaska’s black community, while demonstrating how these women and men have endured racism, fought injustice, and made a life and home for themselves in the forty-ninth state. Indeed, what one then ÿnds in this book is a history not well known, a history of African Americans in the last frontier. Ian C. Hartman / Ed Wesley C. Hartman Ian National Park Service by Ian C. Hartman University of Alaska Anchorage With a Foreword by Ed Wesley Black History in the Last Frontier by Ian C. Hartman With a Foreword by Ed Wesley National Park Service University of Alaska Anchorage 1 Hartman, Ian C. Black History in the Last Frontier ISBN 9780996583787 National Park Service University of Alaska Anchorage HIS056000 History / African American Printed in the United States of America Edited by Kaylene Johnson Design by David Freeman, Anchorage, Alaska. -

Alaska Democratic State Convention

HUMPHREY FOR PRESIDENT COMMITTEE --Su.ite. _]40. _Roosevelt Ho.tei FOR RELEASE: Sunday A.M.'s January 17, 1960 C ~. - \..]ashington 9, D ~ .... · ADams 2-3411 · · · ·· · EXCERPTS OF REMARKS OF SENATOR HUBERT H. HUMPHREY ALASKA STATE DEMOCRATIC COMMITTEE DINNER Ketchikan, Alaska, January 16, 1960 "vlhen I voted in the Senate repeatedly for Statehood for Alaska, it was because I was convinced it was in the clear interest of the Union as well as , the interest of the Territory that Alaska become a State. It definitely was not to bring down on you an avalanche of Presidential candidates of assorted parties clamorin~ for your support. "Nevertheless that seems to have been an inevitable result. You can 'consider it as an extra added penalty or privilege, as you will, that goes with the responsibilities of Statehood. So here I am, in the parade of can didates, semi.-candidates and crypto-candidates from whom you have been receiving visitations. "As the first declared Democratic candidate, I am happy to be address ing the Democratic leaders in a Democratic convention in this new Democratic State. I am proud to be here by your invitation, tendered through your Chairman, Felix J. Toner, and at the urging of my good friends 'and your Senators, Bob Bartlett and Ernest Gruening, your Congressman, Ralph Rivers, your fine Governor, William Egan, his Secretary of State, Hugh J. Wade, and others. "You are about to select the first delegation from the State of Alaska to a Presidential nominating convention. And at that convention, I'm to make my inaugural appearance as a candidate for the Presidential nomination. -

The Alaska Statehood Act Does Not Guarantee Alaska Ninety Percent of the Revenue from Mineral Leases on Federal Lands in Alaska

COMMENTS The Alaska Statehood Act Does Not Guarantee Alaska Ninety Percent of the Revenue from Mineral Leases on Federal Lands in Alaska Ivan L. Ascott" I. INTRODUCTION Alaska is the largest state in the Union.1 At over 365 million acres, it is one-fifth as large as the contiguous forty-eight states.2 Alaska also has a proportionately large share of federal land within its borders.3 The U.S. government owns 220.8 million acres in Alaska, which is over sixty percent of the land in the state.4 It is significant for Alaska that such a large amount of the state's land is under federal control because Alaska's economy depends on natural resource use. In particular, oil fuels the state's economic engine and contributes about eighty percent of the tax revenues for state government.' Alaskan oil is also important to the rest of the country because it accounts for about fifteen percent of domestic production.6 The most likely, and perhaps last, site for development of a major new oilfield in Alaska is in the coastal plain of the Arctic * J.D. cum laude 2004, Seattle University School of Law. The author would like to thank Alaska statehood supporters George and Mary Sundborg for generously creating the Alaska Scholarship for Alaskans to study law at Seattle University. 1. CLAUS M. NASKE & HERMAN E. SLOTNICK, ALASKA: A HISTORY OF THE 49TH STATE 5 (Univ. of Okla. Press 1987) (1979). 2. U.S. CENSUS BUREAU, STATISTICAL ABSTRACT OF THE UNITED STATES, 226 tbl. 360 (123rd ed. -

MASTER's THESIS M-1800 CLINES, Jr., Carroll V. ALASKA's PRESS and the BATTLE for STATEHOOD. the American University, M.A., 1969

MASTER'S THESIS M-1800 CLINES, Jr., Carroll V. ALASKA'S PRESS AND THE BATTLE FOR STATEHOOD. The American University, M.A., 1969 Journalism University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Carroll V. Glines, Jr. 1969 ©. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ALASKA'S PRESS AND THE BATTLE FOR STATEHOOD by Carroll V. Glines Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Journalism Signatures of Committ Chairman Z Dean of the College Date ; ^ Date: y . n ( > 9 AMERICAN UNiVtKbii LIBRARY 1969 APR 11 1969 The American University Washington, D.C. WASHINGTON. D ^ PREFACE Alaska is the largest of the fifty states in size, yet has fewer people living there than reside in Rhode Island, the smallest state. It is a land of mystery and stark con trasts and for all practical purposes is as much an island as is the State of Hawaii. Alaska lies mostly above the 60th parallel where the massive North American and Asian continents nearly touch each other before they flow apart to edge the widening expanses of the Pacific Ocean. No railroad connects the forty-ninth state with the "Lower 48." The Alaska Highway, still an unimproved clay and gravel surfaced country road, cannot be considered an adequate surface artery connecting Alaskan communities either with their Canadian neighbors or other American communities. Sea transportation, augmented by air transportation, remains the primary method of commerce. It is estimated that about 99 per cent of the state's imports and exports are water- transported, leaving only one per cent to be shipped by air or over the Alaska Highway. -

Ernest Gruening: Journalist to U.S

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1983 Ernest Gruening: Journalist to U.S. senator Tom Alton The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Alton, Tom, "Ernest Gruening: Journalist to U.S. senator" (1983). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5051. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5051 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th is is an unpublished manuscript in which copyright sub s is t s . A ny further repr in ting of its contents must be approved BY THE AUTHOR. Man sfield L ibrary Un iv e r s it y Da t e : ________ Er n e s t g r u e n in g : JOURNALIST TO U.S. SENATOR By Tom Alton B .A ., U n iv e rs ity o f A laska, 1974 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1983 Approved by: C.E Uoq-o Chairman, Board of Examiners ean, G raduate SofTool Date UMI Number: EP40515 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Alaska Native History and Cultures Timeline

Alaska Native History and Cultures Timeline 1741 and before 1648 Russian Semeon Dezhnev sails through Bering Strait and lands in the Diomede Islands. Russians in Siberia are aware of trade between Alaska, Chukchi, and Asiatic Eskimos. 1732 Russians M.S. Gvozdev and Ivan Fedorov in the Sv. Gabriel venture north from the Kamchatka Peninsula. Expedition members go ashore on Little Diomede Island and later sight the North America mainland at Cape Prince of Wales and King Island. Contacts with Natives are recorded. 1732- Russian expedition under Mikhail Gvozdev sights or lands on Alaska 1741 to 1867 1741 Vitus Bering, captain of the Russian vessel the St. Peter, sends men ashore on Kayak Island near today’s Cordova. Naturalist Georg Steller and Lt. Khitrovo collect ethnographic items during the time they spend on the island. This is generally accepted as the European discovery of Alaska because of the records and charts kept during the voyage. A month later, Bering makes contact with Native people near the Shumagin Islands. 1741 Several days before Bering saw land, Alexei Chirikov, captain of the St. Paul that had been separated from Bering’s vessel the St. Peter in a storm, sights land in Southeast Alaska. He sends two parties ashore, neither of which return. One day Natives in a canoe come from shore toward the ship, but no contact is made. With supplies low and the season growing late, the St. Paul heads back to Kamchatka. At Adak Island in the Aleutian Islands, Chirikov trades with Aleut men. According to oral tradition, the Tlingit of Southeast Alaska accepted the men into their community.