Collective Memory, Tragedy, and Participatory Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DJ Skills the Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 3

The Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 1 74 The Rise of The Hip-hop DJ DJs were Hip-hop’s original architects, and remain crucial to its contin- ued development. Hip-hop is more than a style of music; it’s a culture. As with any culture, there are various artistic expressions of Hip-hop, the four principal expressions being: • visual art (graffiti) • dance (breaking, rocking, locking, and popping, collectively known in the media as “break dancing”) • literature (rap lyrics and slam poetry) • music (DJing and turntablism) Unlike the European Renaissance or the Ming Dynasty, Hip-hop is a culture that is very much alive and still evolving. Some argue that Hip-hop is the most influential cultural movement in history, point- ing to the globalization of Hip-hop music, fashion, and other forms of expression. Style has always been at the forefront of Hip-hop. Improvisation is called free styling, whether in rap, turntablism, breaking, or graf- fiti writing. Since everyone is using the essentially same tools (spray paint for graffiti writers, microphones for rappers and beat boxers, their bodies for dancers, and two turntables with a mixer for DJs), it’s the artists’ personal styles that set them apart. It’s no coincidence that two of the most authentic movies about the genesis of the move- ment are titled Wild Style and Style Wars. There are also many styles of writing the word “Hip-hop.” The mainstream media most often oscillates between “hip-hop” and “hip hop.” The Hiphop Archive at Harvard writes “Hiphop” as one word, 2 DJ Skills The Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 3 with a capital H, embracing KRS-ONE’s line of reasoning that “Hiphop Kool DJ Herc is a culture with its own foundation narrative, history, natives, and 7 In 1955 in Jamaica, a young woman from the parish of Saint Mary mission.” After a great deal of input from many people in the Hip-hop community, I’ve decided to capitalize the word but keep the hyphen, gave birth to a son who would become the father of Hip-hop. -

Is Graffiti Art?

IS GRAFFITI ART? Russell M. Jones A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2007 Committee: Andrew Hershberger, Advisor Allie Terry ii ABSTRACT Dr. Andrew Hershberger, Advisor Illegal graffiti is disconnected from standard modes of visual production in fine art and design. The primary purpose of illegal graffiti for the graffiti writer is not the visual product, but “getting up.” Getting up involves writing or painting one’s name in as many places as possible for fame. The elements of risk, freedom and ritual unique to illegal graffiti serve to increase camaraderie among graffiti writers even as an individual’s fame in the graffiti subculture increases. When graffiti has moved from illegal locations to the legal arenas of fine art and advertising; risk, ritual and to some extent, camaraderie, has been lost in the translation. Illegal graffiti is often erroneously associated with criminal gangs. Legal modes of production using graffiti-style are problematic in the public eye as a result. I used primary and secondary interviews with graffiti writers in this thesis. My art historical approach differed from previous writers who have used mainly anthropological and popular culture methods to examine graffiti. First, I briefly addressed the extremely limited critical literature on graffiti. In the body of the thesis, I used interviews to examine the importance of getting up to graffiti writers compared to the relative unimportance of style and form in illegal graffiti. This analysis enabled me to demonstrate that illegal graffiti is not art. -

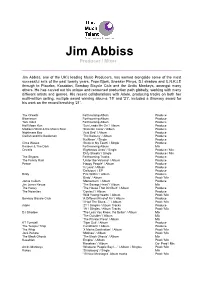

Jim Abbiss Producer / Mixer

Jim Abbiss Producer / Mixer Jim Abbiss, one of the UK’s leading Music Producers, has worked alongside some of the most successful acts of the past twenty years. From Bjork, Sneaker Pimps, DJ shadow and U.N.K.LE through to Placebo, Kasabian, Bombay Bicycle Club and the Arctic Monkeys, amongst many others. He has carved out his unique and renowned production path globally, working with many different artists and genres. His recent collaborations with Adele, producing tracks on both her multi-million selling, multiple award winning albums '19' and '21', included a Grammy award for his work on the record breaking ‘21’. The Orwells Forthcoming Album Produce Blaenavon Forthcoming Album Produce Tom Odell Forthcoming Album Produce Half Moon Run ‘Sun Leads Me On’ / Album Produce Madisen Ward & the Mama Bear ‘Skeleton Crew’ / Album Produce Nightmare Boy ‘Acid Bird’ / Album Produce Catfish and the Bottlemen ‘The Balcony’ / Album Produce ‘Kathleen’ / Single Produce Circa Waves ‘Stuck in My Teeth’ / Single Produce Reuben & The Dark Forthcoming Album Mix Orwells ‘Righteous Ones’ / Single Produce / Mix ‘Dirty Sheets’ / Single Produce / Mix The Strypes Forthcoming Tracks Produce The Family Rain ‘Under the Volcano’ / Album Produce Peace ‘Happy People’ / Album Produce ‘In Love’ / Album Produce ‘Delicious’ / EP Produce Birdy ‘Fire Within’ / Album Produce ‘Birdy’ / Album Prod / Mix Jamie Cullum ‘Momentum’ / Album Produce Jim Jones Revue ‘The Savage Heart’ / Album Mix The Heavy ‘The House That Dirt Built’ / Album Produce The Noisettes ‘Contact’ / Album Produce -

Simplicity Two Thousand (M

ELECTRONICA_CLUBMUSIC_SOUNDTRACKS_&_MORE URBANI AfterlifeSimplicityTwoThousand AfterlifeSimplicityTwoThousand(mixes) AirTalkieWalkie Apollo440Gettin'HighOnYourOwnSupply ArchiveNoise ArchiveYouAllLookTheSameToMe AsianDubFoundationRafi'sRevenge BethGibbons&RustinManOutOfSeason BjorkDebut BjorkPost BjorkTelegram BoardsOfCanadaMusicHasTheRightToChildren DeathInVegasScorpioRising DeathInVegasTheContinoSessions DjKrushKakusei DjKrushReloadTheRemixCollection DjKrushZen DJShadowEndtroducing DjShadowThePrivatePress FaithlessOutrospective FightClub_stx FutureSoundOfLondonDeadCities GorillazGorillaz GotanProjectLaRevanchaDelTango HooverphonicBlueWonderPowerMilk HooverphonicJackieCane HooverphonicSitDownAndListenToH HooverphonicTheMagnificentTree KosheenResist Kruder&DorfmeisterConversionsAK&DSelection Kruder&DorfmeisterDjKicks LostHighway_stx MassiveAttack100thWindow MassiveAttackHits...BlueLine&Protection MaximHell'sKitchen Moby18 MobyHits MobyHotel PhotekModusOperandi PortisheadDummy PortisheadPortishead PortisheadRoselandNYCLive Portishead&SmokeCityRareRemixes ProdigyTheCastbreeder RequiemForADream_stx Spawn_stx StreetLifeOriginals_stx TerranovaCloseTheDoor TheCrystalMethodLegionOfBoom TheCrystalMethodLondonstx TheCrystalMethodTweekendRetail TheCrystalMethodVegas TheStreetsAGrandDon'tComeforFree ThieveryCorporationDJKicks(mix1999) ThieveryCorporationSoundsFromTheThieveryHiFi ToxicLoungeLowNoon TrickyAngelsWithDirtyFaces TrickyBlowback TrickyJuxtapose TrickyMaxinquaye TrickyNearlyGod TrickyPreMillenniumTension TrickyVulnerable URBANII 9Lazy9SweetJones -

Strona 1 NAZWA ILOŚĆ STARA CENA NOWA CENA 54 1 89,50 Zł 45 Zł 311 SOUND SYSTEM 1 42,50 Zł 21 Zł 666 PARADOXX 2 49,50 Zł 2

NAZWA ILOŚĆ STARA CENA NOWA CENA MUSIC FROM THE MIRAMAX 54 1 89,50 zł 45 zł MOTION PICTURE (2CD) 311 SOUND SYSTEM 1 42,50 zł 21 zł 666 PARADOXX 2 49,50 zł 25 zł 911 MOVING ON 1 51,50 zł 26 zł 10 CC MIRROR MIRROR 1 43,50 zł 22 zł 100% GINUWINE 100% GINUWINE 1 49,50 zł 25 zł 1996 GRAMMY NOMINEES 1996 GRAMMY NOMINEES 1 59,50 zł 30 zł 2 TM 2,3 2 TM 2,3 1 39,50 zł 20 zł 50 GOLDEN MILESTONES 50 GOLDEN MILESTONES VOL.2 1 54,50 zł 27 zł VOL.2 8 TRACK PROMO CD OF 8 TRACK PROMO CD OF 1 39,50 zł 20 zł UNDERGROUND GARAGE UNDERGROUND GARAGE A TASTE OF SUCCESS 1 9,90 zł 5 zł A. HI-FI SERIOUS A. HI-FI SERIOUS 1 63,00 zł 32 zł A+ HEMPSTEAD HIGH 1 53,50 zł 27 zł ABRAXAS 99,00 zł 1 53,50 zł 27 zł ACE VENTURAWHEN NATURE MUSIC FROM ORIGINAL 1 48,50 zł 24 zł CALLS MOTION PICTURE ACID DRINKERS BROKEN HEAD 1 42,50 zł 21 zł ADAM F COLOURS 1 59,50 zł 30 zł AIR 10 000 Hz LEGEND 2 63,00 zł 32 zł AKA SLAVE TO THE SOUND 1 59,50 zł 30 zł ALANIS MORISSETTTE FEAST ON SCRAPS (CD+DVD) 1 63,00 zł 32 zł ALI CAMPBELL BIG LOVE 1 42,50 zł 21 zł ALIEN ANT FARM ANTHOLOGY 1 54,50 zł 27 zł _10 ALINE CAN DANCE ORIGINAL.HOUSE.TRAKS.FRO 1 47,50 zł 24 zł M.PARIS ALL-4-ONE ALL-4-ONE 1 39,50 zł 20 zł ALLA PUGACHEVA THE BEST SONGS 1 29,50 zł 15 zł AMANDA MARSHALL BELIEVE IN YOU 1 23,50 zł 12 zł AMEDEO MINGHI DECENNI 2 52,50 zł 26 zł AMERICA'S SWEETHEARTS ORIGINAL SOUNDTRACK 1 63,00 zł 32 zł MUSIC FROM ORIGINAL AMERICAN BEAUTY 2 59,50 zł 30 zł SOUNDTRACK ANDY WARHOL AMERYKAŃSKI MIT 1 49,50 zł 25 zł ANGEL DUST OF HUMAN BONDAGE 1 65,00 zł 33 zł Strona 1 ANJALI ANJALI 1 49,50 zł 25 zł ANJALI -

Jim Abbiss Complete CV

Jim Abbiss Producer/Mixer Jim Abbiss, one of the UK’s leading Music Producers, has worked alongside some of the most successful acts of the past twenty years. From Bjork to The Arctic Monkeys, Faithless and Placebo, he has uniquely carved his way through the UK and International music scenes. His more recent successes take shape with his ongoing, Grammy-award winning collaboration with Adele on her multi-platinum albums ‘19’ and ‘21’, released to worldwide critical acclaim. The Family Rain Forthcoming Album Produce Peace ‘In Love’ / Album Produce ‘Delicious’ / EP Produce Jamie Cullum ‘Momentum’ / Album Produce Jim Jones Revue ‘The Savage Heart’ / Album Mix The Heavy ‘The House That Dirt Built’ / Album Produce Birdy Forthcoming Album Produce ‘Birdy’ / Album Produce/Mix The Noisettes ‘Contact’ / Album Produce ‘Wild Young Hearts’ / Album Produce / Mix Bombay Bicycle Club ‘A Different Kind of Fix’ / Album Produce “I Had The Blues…” / Album Produce / Mix Adele ‘21’ / Singles / Album Tracks Produce ’19’ / Singles / Album Tracks’ Produce / Mix DJ Shadow ‘The Less You Know, the Better’ / Album Mix ‘The Outsider’ / Album Mix ‘The Private Press’ / Album Mix KT Tunstall ‘Tiger Suit’ / Album Produce The Temper Trap ‘Conditions’ / Album Produce The Whip ‘X Marks Destination’ / Album Produce / Mix Jack Penate ‘Matinee’ / Album Produce / Mix The Black Ghosts ‘The Black Ghosts’ / Album Mix Kasabian ‘Empire’ / Album Produce / Mix ‘Kasabian’ / Album Co- Prod / Mix Arctic Monkeys ‘Whatever People Say I…’ / Album Produce / Mix Rakes ‘Strasbourg’ / Album -

The BG News October 9, 1998

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 10-9-1998 The BG News October 9, 1998 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News October 9, 1998" (1998). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6382. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6382 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. FRIDAY,The Oct. 9,1998 A dailyBG independent student News press Volume 85» No. 31 BGSU Fact One... educates Can I help on binge drinking □ Bowling Green has ■ Heather Murphy is sev- you? received a grant to aid enth in the nation for her in teaching students kills per game. about binge drinking. By CAROLYN STECKEL ■ The Falcon hocKey The BG News team opens its confer- Imagine what the typical Fri- ence schedule against Fact Line continues day night of an average student is like. Perhaps it includes an the Redhawks. hour or two of primping and to answer questions then meeting up with friends. From there a quick alcohol run and then off to someone's apart- ■ The Bowling Green ment for a night of drinking and despite problems socializing. football teamk travels to At the party, an average stu- Oxford to play a tough On May 4, 1970, the Kent dent might throw back two Jack Miami team. -

Exit Music: Can Radiohead Save Rock Music As We (Don't) Know

Exit Music: Can Radiohead save rock music as we (don’t) know it? GQ, October 2000 THE POSTERS on the ancient streets of Arles give little away. Sting is playing soon in Marseille, and coming up is a "Super Big Reggae Party" with U Roy and Alpha Bondy. A bullfight will take place next week in the town’s ancient Roman amphitheater. Even as one approaches the equally ancient "Theatre Antique", built during the reign of the Emperor Augustus, there’s scant indication that the most acclaimed group on Planet Pop is here, in Provence, to play its first live show in 18 months. On one side of the open-air auditorium the evening sky is charcoal-grey; from the other, bright golden light streams across crumbling columns and arches. But now the old men promenading with their tiny dachshunds pause in their post-prandial tracks. For covering the railings which encircle the theatre are sheets of black plastic, and towering over the old brickwork is scaffolding that supports chunky klieg lights. Clustered about the theatre’s back entrance is a polyglot throng of youths. A shiver of excitement ripples through the boys and girls as a slight dark figure emerges from the doorway. No satin or sunglasses on display here; not even a tattoo. Just a guy in grey New Balance sneakers, bag slung over shoulder and head tilted into a mobile phone. Voices – French, German, Dutch, English – yap at Colin Greenwood, bass player with Radiohead, as he follows the band’s producer Nigel Godrich into the sharp light. -

Cob Records Porthmadog, Gwynedd, Wales

COB RECORDS PORTHMADOG, GWYNEDD, WALES. LL49 9NA Tel:01766-512170. Fax: 01766 513185 www.cobrecords.com e-mail [email protected] CD RELEASES & RE-ISSUES JANUARY 2001 – DECEMBER 2003 “OUR 8,000 BEST SELLERS” ABOUT THIS CATALOGUE This catalogue lists the most popular items we have sold over the past three years. For easier reading the three year compilation is in one A-Z artist and title formation. We have tried to avoid listing deletions, but as there are around 8,000 titles listed, it is inevitable that we may have inadvertently included some which may no longer be available. For obvious reasons, we do not actually stock all listed titles, but we can acquire them to order within days providing there are no stock problems at the manufacturers. There are obviously tens of thousands of other CDs currently available – most of them we can supply; so if what you require is not listed, you are welcome to enquire. Please read this catalogue in conjunction with our “CDs AT SPECIAL DISCOUNT PRICES” as some of the more mainstream titles may be available at cheaper prices in that feature. Please note that all items listed on this catalogue are of U.K. manufacture (apart from Imports denoted IM or IMP). Items listed on our Specials are a mix of U.K. and E.C. manufacture; we will supply you the items for the price/manufacturer you chose. ******* WHEN ORDERING FROM THIS CATALOGUE PLEASE QUOTE CAT 01/03 ******* the visitors r/m 8.50 live 7.50 ALCHEMY live at t’ fillmore east deluxe 16.50 tales of alibrarian coll’n+ DVD 20.00 10 CC voulez vous r/m 8.50 -

Vinyl News 1. Quartal 2019 HP.Xlsx

Artist Title Units Media Genre Release A MODE OF DUST II 1 LP AMB 01.03.2019 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH WHEN THE WORLD.. -HQ- 2 LP HM. 17.01.2019 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH WHEN THE.. -COLOURED- 3 LP HM. 17.01.2019 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS FUZZ CLUB SESSION 1 LP ROC 15.02.2019 A SECRET REVEALED SACRIFICES -GATEFOLD- 2 LP PUN 25.01.2019 A SWARM OF THE SUN WOODS -GATEFOLD- 1 LP ROC 10.01.2019 AARON 7-JOS VOIS 1 12in POP 25.01.2019 ABANDONED KILLED BY FAITH -REISSUE- 1 LP PUN 10.01.2019 ABERNATHY, AARON EPILOGUE 2 LP SOU 01.02.2019 ABRUPTUM VI SONUS VERIS NIGRAE MAL 2 LP EXP 25.01.2019 ABSENT TOWARDS THE VOID 1 LP ROC 31.01.2019 ABSOLUUTTINEN NOLLAPISTE ROVANIEMI 1993 -COLOURED- 2 LP ROC 22.02.2019 ABSOLUUTTINEN NOLLAPISTE ROVANIEMI 1993 -LTD- 2 LP ROC 22.02.2019 ABSOLUUTTINEN NOLLAPISTE SIMPUKK.. -COLOURED- 2 LP ROC 22.02.2019 ABSOLUUTTINEN NOLLAPISTE SIMPUKKA-AMPPELI -LTD- 2 LP ROC 22.02.2019 AC/DC IN THE BEGINNING 1 LP ROC 03.01.2019 ACACIA STRAIN CONTINENT -COLOURED/LTD- 1 LP HC. 18.01.2019 ACACIA STRAIN CONTINENT -COLOURED/LTD- 1 LP HC. 18.01.2019 ACETONE 1992-2001 2 LP ROC 17.01.2019 ACETONE 1992-2001 -GATEFOLD- 2 LP ROC 25.01.2019 ACHILIFUNK SOUND SYSTEM CASIOPONY 1 LP FNK 18.01.2019 ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE & THE SACRED AND INVIOLABLE.. 1 LP ROC 15.02.2019 ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE & THE MELTING PARAISO U.F.O. -

British Project UNKLE Live at Spirit of Burgas

TCPDF Example British Project UNKLE Live at Spirit of Burgas Thursday, 08 July 2010 On the second festival night, August 14th, when DJ Shadow will extract unique sound from its digital players, his mates from UNKLE will also go on the main stage of the biggest summer sea festival on the Balkans. Behind the name of UNKLE are two main figures - James Lavelle and Tim Goldsworthy from London. But for their live in Burgas they will come with a whole band to make one-of-a-kind live - musicians Joel Cadbury, Pablo Clements and James Griffith, drummer Michael Lowry and singer Gavin Clark. They will come to Burgas with solid video and lighting effects equipment. So what we may expect is a great mix of live music, lighting show and attractive visual effects. Three things make UNKLE a remarkable project. First is, that since 1994 they have never stopped to take creative risks and experiment beyond the traditional. UNKLE actually starts as a label and if we trace back the development of their music ideas we will find significant differences in the way they sound from the middle 90s by now. The second thing is that they manage to attract to their studio project many famous figures from the world stage. Producer of their debut album "Psyence Fiction" is DJ Shadow and guest musicians are Thom Yorke from Radiohead and Jason Newstead from Metallica, Mike D from Beasty Boys, Kool G Rap, Badly Drawn Boy and Richard Ashkroft from The Verve. In "Never, Never, Land" /2003/, "War Stories" /2007/ and "End Title.. -

Jim Abbiss Complete CV

Jim Abbiss Producer / Mixer Jim Abbiss, one of the UK’s leading Music Producers, has worked alongside some of the most successful acts of the past twenty years. From Bjork, Sneaker Pimps, DJ shadow and U.N.K.LE through to Placebo, Kasabian, Bombay Bicycle Club and the Arctic Monkeys, amongst many others. He has carved out his unique and renowned production path globally, working with many different artists and genres. His recent collaborations with Adele, producing tracks on both her multi-million selling, multiple award winning albums '19' and '21', included a Grammy award for his work on the record breaking ‘21’. Briston Maroney ‘Steve’s First Bruise’ / Single Produce Mosa Wild ‘Night’ / Single Produce ‘Tides’ / Single Produce Nova Twins ‘Devil’s Face’ / Single Produce Zuzu ‘How It Feels’ / Single Produce ‘Get Off’ / Single Produce Tom Walker ‘What A Time To Be Alive’ / Album tracks Produce ‘Blessings’ / EP Produce Connie Constance ‘Yesterday’ / Single Produce ‘English Rose’ / Album tracks Produce Lush Forthcoming Tracks Produce Ladytron ‘Witching Hour’ / Album Prod / Mix ‘Evil’ / ‘Blue Jeans’ / Singles Add Prod / Mix ‘Ladytron’ / Album Produce Machineheart ‘People Change’ / Album Produce Tojin Kit ‘Vapour’ / EP Co-Write / Prod HMLTD ‘Proxy Love’ / Single Produce ‘Satan, Luella & I’ / Single Co-Write Blaenavon ‘That’s Your Lot’ / Album Produce The Orwells ‘Terrible Human Beings’ / Album Produce ‘Righteous Ones’ / Single Produce / Mix ‘Dirty Sheets’ / Single Produce / Mix Nic Cester Forthcoming Album Produce Tom Odell ‘Wrong Crowd’ /