A Contemporary Proposal for Reconciling the Free Speech Clause with Curricular Values Inculcation in the Public Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol L Issue 5

page 2 the paper december 6, 2017 GOP Tax plan, pg. 3 Seniors, pg. 9 Da Vinci sale, pg. 15 F & L, pg. 21-22 Earwax, pg. 23 the paper “Favorite Vines” c/o Office of Student Involvement Editors-in-Chief Fordham University John “Dad look, it’s the good kush” Looby Bronx, NY 10458 Luis “Me and my boys are going to see Uncle Kracker” Gómez [email protected] News Editors http://fupaper.blog/ Nick “What’s the number” Peters Declan “I can’t believe you’ve done this” Murphy the paper is Fordham’s journal of news, analysis, comment and review. Students from all Opinions Editors years and disciplines get together biweekly to produce a printed version of the paper using Colleen “Happy Crismns” Burns Adobe InDesign and publish an online version using Wordpress. Photos are “borrowed” from Rachel “Welcome to bible study, we’re all children of Jesus” Poe Internet sites and edited in Photoshop. Open meetings are held Tuesdays at 9:00 PM in McGin- ley 2nd. Articles can be submitted via e-mail to [email protected]. Submissions from Arts Editors students are always considered and usually published. Our staff is more than willing to help Matthew “Chris! Is that a weed?” Whitaker new writers develop their own unique voices and figure out how to most effectively convey their Michael “Two shots of vodka” Sheridan thoughts and ideas. We do not assign topics to our writers either. The process is as follows: Earwax Editor have an idea for an article, send us an e-mail or come to our meetings to pitch your idea, write Reyna “...yes” Wang the article, work on edits with us, and then get published! We are happy to work with anyone who is interested, so if you have any questions, comments or concerns please shoot us an e- Features and List Editors mail or come to our next meeting. -

DC Comics Jumpchain CYOA

DC Comics Jumpchain CYOA CYOA written by [text removed] [text removed] [text removed] cause I didn’t lol The lists of superpowers and weaknesses are taken from the DC Wiki, and have been reproduced here for ease of access. Some entries have been removed, added, or modified to better fit this format. The DC universe is long and storied one, in more ways than one. It’s a universe filled with adventure around every corner, not least among them on Earth, an unassuming but cosmically significant planet out of the way of most space territories. Heroes and villains, from the bottom of the Dark Multiverse to the top of the Monitor Sphere, endlessly struggle for justice, for power, and for control over the fate of the very multiverse itself. You start with 1000 Cape Points (CP). Discounted options are 50% off. Discounts only apply once per purchase. Free options are not mandatory. Continuity === === === === === Continuity doesn't change during your time here, since each continuity has a past and a future unconnected to the Crises. If you're in Post-Crisis you'll blow right through 2011 instead of seeing Flashpoint. This changes if you take the relevant scenarios. You can choose your starting date. Early Golden Age (eGA) Default Start Date: 1939 The original timeline, the one where it all began. Superman can leap tall buildings in a single bound, while other characters like Batman, Dr. Occult, and Sandman have just debuted in their respective cities. This continuity occurred in the late 1930s, and takes place in a single universe. -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

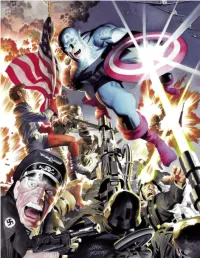

#19 Contents: THE $5.95 In The US SIDE A Cover painting by Alex Ross . .1 Inside cover painting by Jack Kirby (date unknown) . .2 Gil Kane on Kirby . .4 Joe Kubert Interview . .6 Issue #19, April 1998 Collector Kevin Eastman Interview . .10 A Home Fit For A King . .13 Hour Twenty-Five . .14 (with Kirby, Evanier, Miller, & Gerber) Gary Groth Interview . .18 The Stolen Art . .20 Collector Comments . .22 Classifieds . .24 Kirby Paintings . .27 Centerfold: Captain America . .28 (Inks by Dave Stevens, color by Homer Reyes and Dave Stevens) SIDE B Cover inked by Ernie Stiner (Color by Tom Ziuko) . .1 Inside cover inked by John Trumbull (Color by Tom Ziuko) . .2 Kirby Collector Bulletins . .3 The Kirby Squiggle . .4 A Monologue on Dialogue . .6 Kirby Forgeries . .7 The Art of Collecting Kirby . .10 A Provenance of Kirby’s Thor . .12 Art History Kirby-Style . .14 Silver Star Art . .15 The Kirby Flow . .16 Master of Storytelling Technique . .17 The Drawing Lesson . .17 A Total Taxonomy . .18 Jack Kirby’s Inkers . .20 Inking Contest Winners . .22 In Memorium: Roz Kirby . .24 Kirby Paintings . .27 Photocopies of Jack’s uninked pencils from published comics are reproduced here courtesy of the Kirby Estate, which has our thanks for their continued support. COPYRIGHTS: Balder, Black Bolt, Black Panther, Bucky, Captain America, Eternals, Falcon, Fandral, Fantastic Four, Hogun, Human Torch, Ikaris, Ka-Zar, Machine Man, Mangog, Mole Man, Mr. Fantastic, Pluto, Sersi, Sgt. Fury & His Howling Commandos, Sif, Silver Surfer, Our cover painting by Alex Ross is based on this Kirby pencil drawing, originally published in The Steranko History Thing, Thor, Ulik, X-Men, Zabu © Marvel Entertainment, Inc. -

BATMAN: a HERO UNMASKED Narrative Analysis of a Superhero Tale

BATMAN: A HERO UNMASKED Narrative Analysis of a Superhero Tale BY KELLY A. BERG NELLIS Dr. William Deering, Chairman Dr. Leslie Midkiff-DeBauche Dr. Mark Tolstedt A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communication UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN Stevens Point, Wisconsin August 1995 FORMC Report of Thesis Proposal Review Colleen A. Berg Nellis The Advisory Committee has reviewed the thesis proposal of the above named student. It is the committee's recommendation: X A) That the proposal be approved and that the thesis be completed as proposed, subject to the following understandings: B) That the proposal be resubmitted when the following deficiencies have been incorporated into a revision: Advisory Committee: Date: .::!°®E: \ ~jjj_s ~~~~------Advisor ~-.... ~·,i._,__,.\...,,_ .,;,,,,,/-~-v ok. ABSTRACT Comics are an integral aspect of America's development and culture. The comics have chronicled historical milestones, determined fashion and shaped the way society viewed events and issues. They also offered entertainment and escape. The comics were particularly effective in providing heroes for Americans of all ages. One of those heroes -- or more accurately, superheroes -- is the Batman. A crime-fighting, masked avenger, the Batman was one of few comic characters that survived more than a half-century of changes in the country. Unlike his counterpart and rival -- Superman -- the Batman's popularity has been attributed to his embodiment of human qualities. Thus, as a hero, the Batman says something about the culture for which he is an ideal. The character's longevity and the alterations he endured offer a glimpse into the society that invoked the transformations. -

Dark Nights Free

FREE DARK NIGHTS PDF Christine Feehan | 420 pages | 30 Oct 2012 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780062219022 | English | New York, United States Dark Knights - Villains Wiki - villains, bad guys, comic books, anime Link here. Your progress will be carried over automatically after downloading the new version. You live in a small, peaceful village. Every day is the same as any other; boring. Right when you wish for something exciting to happen, strange things start to occur, stemming from the nearby forest. If that isn't enough, the locals have begun disappearing. At the same time you meet four mysterious guys. Will you discover the truth before becoming the next target? Q: Will there be a suggested route order? Although, some routes are more connected than others. Like Zeikun and Sachiro. If you are going to play all routes anyway, I suggest to start off with Zeikun or Sachiro as an introduction to the story. Official Site — Development blog and info about the game. Tumblr — Mostly doodles and short notices. Full walk-through by Emi. Full walk-through 2 by Alice. If you enjoy the content, please support us! Dark Nights will help us with the progress and work on more content. Log in with itch. First of all thanks for the game I really Dark Nights it! Hello I haven't beat the game yet but just wanted to say so far I'm really enjoying it. I'm on Day 11 Dark Nights Kurato's route. It's not a perfect game, like Tigress said there are some issues with lack of world building or characters accepting some pretty odd things without question. -

![Incorporating Flow for a Comic [Book] Corrective of Rhetcon](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7100/incorporating-flow-for-a-comic-book-corrective-of-rhetcon-2937100.webp)

Incorporating Flow for a Comic [Book] Corrective of Rhetcon

INCORPORATING FLOW FOR A COMIC [BOOK] CORRECTIVE OF RHETCON Garret Castleberry Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2010 APPROVED: Brian Lain, Major Professor Shaun Treat, Co-Major Professor Karen Anderson, Committee Member Justin Trudeau, Committee Member John M. Allison Jr., Chair, Department of Communication Studies Michael Monticino, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Castleberry, Garret. Incorporating Flow for a Comic [Book] Corrective of Rhetcon. Master of Arts (Communication Studies), May 2010, 137 pp., references, 128 titles. In this essay, I examined the significance of graphic novels as polyvalent texts that hold the potential for creating an aesthetic sense of flow for readers and consumers. In building a justification for the rhetorical examination of comic book culture, I looked at Kenneth Burke’s critique of art under capitalism in order to explore the dimensions between comic book creation, distribution, consumption, and reaction from fandom. I also examined Victor Turner’s theoretical scope of flow, as an aesthetic related to ritual, communitas, and the liminoid. I analyzed the graphic novels Green Lantern: Rebirth and Y: The Last Man as case studies toward the rhetorical significance of retroactive continuity and the somatic potential of comic books to serve as equipment for living. These conclusions lay groundwork for multiple directions of future research. Copyright 2010 by Garret Castleberry ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are several faculty and family deserving recognition for their contribution toward this project. First, at the University of North Texas, I would like to credit my co-advisors Dr. Brian Lain and Dr. -

Batman/Superman/Wonder Woman: Trinity Written by Alex Mckinnon

Batman/Superman/Wonder Woman: Trinity Written by Alex McKinnon Batman created by Bob Kane Superman created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster Wonder Woman created by William Moulton Marston [email protected] INT. SMALLVILLE DINER A small glob of red ketchup on a white plate. A hand dips and slides a french fry through it in a sunny, relaxed restaurant. CLARK ... and that's how I got out. The hand belongs to CLARK KENT, approaching his twenties, the boy next door in a world without neighbors. He beams a happy, sheepish smile. Two teenagers (a BOY and a GIRL) sit across from him, speechless. GIRL You're not serious. Clark chuckles and gestures 'cross my heart'. GIRL THAT'S your big secret. The girl folds her arms and leans back in her chair, frowning. GIRL I don't believe you. CLARK Honest. The girl slaps the table, laughing incredulously. GIRL Come on! You skipped physics?! That's REALLY the best you got? CLARK I told you it wasn't worth knowing. GIRL But we gave you such good ones! You can't honestly tell me that's all. CLARK What exactly were you expecting? The girl just shrugs. Clark looks around the diner for a waiter. He suddenly looks flushed. He leans forward, elbow on the table, rubbing a hand across his face. GIRL Hey Boy Scout, what's wrong? 2. CLARK Nothing. Clark grabs a menu and hides behind it, coughing, fidgeting. He wipes his brow with the back of his hand. His eyes slowly adopt a tint of red, an odd WHISTLING accompanying the change. -

Hatton I the Flash of War: How Ame.-Ican Patriotism

Hatton I The Flash of War: How Ame.-ican patriotism evolved through the lens of The Flaslt comic boo)(S throughout the Cold War era An Hon01·s Thesis (HONRS 499) by Rachel Hatton Thesis Advisor Professor Ed Krzemi enski Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 201 7 Expected Date of Graduation May 201 7 ( f'1 - LV Hatton 2 ~L}~9 - L j f).OJ7 Abstract Comic book superheroes became a uniquely American phenomenon beginning in the wake of World War TT. The characters and situations often reflected and alluded to contemporary events. Comic books are a vibrant cultural artifact through which people can get a glimpse into the past. The way in which Americans view their country and their faith in the government changed rather drastically between the end of World War II and the end of the Cold War in 1991, when the Soviet Union was officially dissolved. Throughout the duration of this paper, patriotism, as a ideological product of culture, will be looked at through the lens of The Flash and Flash comic book series from 1956 when The Flash reappeared, after a period of censorship and decline in superheroes' popularity post-WWTT, to the beginning of the 1990s. By looking at The Flash specifically, this thesis contributes to more nuanced research and further understanding of culture and the American view of patriotism during the Cold War era, a time of cultural and ideological upheaval. Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Krzemienski for supporting me in this endeavor and understanding when I was at my busiest times of the semester. -

What Does Psychology Know and Understand About the Psychological Effects of Reading Superhero Comic Books?: an Exploration Study

WHAT DOES PSYCHOLOGY KNOW AND UNDERSTAND ABOUT THE PSYCHOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF READING SUPERHERO COMIC BOOKS?: AN EXPLORATION STUDY By PARKER T SHAW Bachelor of Science in Psychology Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2009 Master of Science in Educational Psychology Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2013 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY July, 2017 WHAT DOES PSYCHOLOGY KNOW AND UNDERSTAND ABOUT THE PSYCHOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF READING SUPERHERO COMIC BOOKS?: AN EXPLORATION STUDY Dissertation Approved: John Romans, Ph.D. Dissertation Chair Tonya Hammer, Ph.D. Dissertation Advisor Al Carlozzi, Ed.D. Committee Member Hugh Crethar, Ph.D. Committee Member Larry Mullins, Ph.D. Outside Committee Member ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am so very grateful for all those who sacrificed so that I may have this opportunity. Your sacrifice and support through these years has been so very special to me. I am thankful for my loving wife Katie and my darling daughter Penny Lane. You are my best accomplishments to date. I’m so blessed that you are here with me on this journey. Thank you to my wonderful parents for all the opportunities you gave me through your sacrifices. I hope to carry your legacy with grace. I would like to thank my committee for their guidance and support during this journey. It has been an honor to work alongside you all and learn. Lastly, thank you superheroes. Thank you for always being there. iii Acknowledgements reflect the views of the author and are not endorsed by committee members or Oklahoma State University. -

Justice League Vol. 2: Outbreak (Rebirth) Summary a Part of DC Universe: Rebirth!

PRHPS - Graphic Novel & Manga Newsletter May 2017 Justice League Vol. 2: Outbreak (Rebirth) Summary A part of DC Universe: Rebirth! Spinning directly out of the events of DC UNIVERSE: REBIRTH, a new day dawns for the Justice League as they welcome a slew of new members into their ranks. The question remains though, can the world’s greatest superheroes trust these new recruits? And will the members of League be able to come together against an ancient evil that threatens to reclaim not just the world, but the entire universe! Masterful storytelling, epic action, and unbelievable art come together in JUSTICE LEAGUE from best-selling comic book writer Bryan Hitch (JLA) and superstar artist Tony S. Daniel (BATMAN, DETECTIVE COMICS). Collects JUSTICE LEAGUE #6-11. Rebirth honors the richest history in comics, while continuing to look towards the future. These are the most innovative and modern stories featuring the DC Comics world’s greatest superheroes, told by some of the finest storytellers in the 9781401268701 business. On Sale Date: 5/2/2017 $16.99 Honoring the past, protecting our present, and looking towards the future. This Trade Paperback is the next chapter in the ongoing saga of the DC Universe. The legacy 144 Pages continues. Comics & Graphic Novels / Superheroes Territory: World except UK/Ireland Status:ACTIVE PRHPS - Graphic Novel & Manga Newsletter May 2017 Justice League Unwrapped by Jim Lee Summary SUPERSTAR ARTIST JIM LEE BRINGS TOGETHER THE WORLD’S GREATEST HEROES…FOR THE FIRST TIME! It’s the dawn of a new age. Superheroes—like Superman in Metropolis and Gotham’s Dark Knight, Batman—are new and frightening to the world at large. -

The End of an Era – Or a New Start?

Dr. philos. Dissertation Vegard Bye, Department of Political Science, University of Oslo The End of an Era – or a New Start? Economic Reforms with Potential for Political Transformation in Cuba on Raúl Castro´s Watch (2008-2018). ii To Cuba’s youth, wishing them the opportunity to form a future they can believe in. iii iv INDEX PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................................... IX 1: INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. THE SETTING OF THE STUDY ........................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. OUTLINE OF THE DISSERTATION .................................................................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER 2: RESEARCH DESIGN ......................................................................................................... 11 2.1. THE PROBLEM OF STUDYING POLITICS IN CUBA ..................................................................................................... 11 2.2. INTERPLAY BETWEEN ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL VARIABLES ........................................................................... 14 2.3. RESEARCH STRATEGY ................................................................................................................................................... -

In Comics! in Volume 1, Number 59 September 2012 Celebrating the Best the Retro Comics Experience! Comics of the '70S, '80S, '90S, and Beyond!

Space Ghost TM & © Hanna-Barbera Productions. All Rights Reserved. Sept. 2012 0 8 No.59 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 This issue: TOON COMICS ISSUE: JONNY QUEST • MARVEL PRODUCTIONS, LTD. • STAR BLAZERS • THE RETRO COMICS EXPERIENCE! MARVEL’S HANNA-BARBERA LINE • UNPUBLISHED PLASTIC MAN COMIC STRIP & MORE in comics! Volume 1, Number 59 September 2012 Celebrating the Best The Retro Comics Experience! Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks COVER ARTIST Steve Rude COVER DESIGNER BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 Michael Kronenberg Remembering the late Tony DeZuniga and Ernie Chan. PROOFREADER FLASHBACK: Space Ghost in Comics . .3 John Morrow Steve Rude, Evan Dorkin, and Scott Rosema look back at the different comic-book interpretations of Spaaaaaace Ghoooooost! SPECIAL THANKS Mark Arnold IGN.com BEYOND CAPES: Hanna-Barbera at Marvel Comics . .19 Roger Ash Dan Johnson The Backroom Adam Kubert Mark Evanier, Scott Shaw!, and other toon-types tell the tale of how Yogi and Fred landed Greg Beder Carol Lay at Marvel Jerry Boyd Alan Light DC Comics Karen Machette CHECKLIST: Marvel Hanna-Barbera Comics . .28 Daniel DeAngelo Paul Kupperberg An index of Marvel H-B comics, stories, and creator credits, courtesy of Mark Arnold Evan Dorkin Andy Mangels Tim Eldred Lee Marrs PRINCE STREET NEWS: Hanna-Barbera Superheroes at Marvel Comics? . .32 Jack Enyart William Messner- Karl Heitmueller takes a hilarious look at what might’ve been Mark Evanier Loebs Ron Ferdinand Doug Rice GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: The Plastic Man Comic Strip .