Rhetoric and Taste in AIP's Promotion of Roger Corman's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kubrick Film Streams Supporters Met Op

Film Streams Programming Calendar The Ruth Sokolof Theater . October – December 2008 v2.2 2001: A Space Odyssey 1968 MGM/Photofest Film Screams! October 3 – October 31, 2008 The Cabinet An American Werewolf of Dr. Caligari 1921 in London 1981 Bride of Frankenstein 1935 Evil Dead 2 1987 The Innocents 1961 Eyes Without a Face 1960 Les Diaboliques 1955 The Raven 1963 What better way to celebrate the Halloween and of little worth artistically, that’s hardly the case. The eight films in this month than with a horror series? While other series offer a glimpse of the richness and variety of the genre, in terms of genres, such as musicals and westerns, tend to its history, cultural significance, creative influence, and talent produced. wax and wane in interest over certain periods of Whether deathly terrifying or horribly silly, there is something here for time, horror has maintained a constant presence everyone to enjoy and appreciate. ever since the inception of cinema. And while the — Andrew Bouska, Film Streams Associate Manager and Series Curator genre often bears the stigma of being lowbrow See the reverse side of this newsletter for full calendar of films and dates. Great Directors: Kubrick November 1 – December 11, 2008 2001: A Space Odyssey 1968 Spartacus 1960 Dr. Strangelove 1964 Lolita 1962 The Killing 1956 Barry Lyndon 1975 A Clockwork Orange 1971 Full Metal Jacket 1987 Paths of Glory 1957 Eyes Wide Shut 1999 Almost a decade after his death, the great myth fiction (2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY) to period drama (BARRY LYNDON) to of Stanley Kubrick seems as mysterious as ever. -

CLONES, BONES and TWILIGHT ZONES: PROTECTING the DIGITAL PERSONA of the QUICK, the DEAD and the IMAGINARY by Josephj

CLONES, BONES AND TWILIGHT ZONES: PROTECTING THE DIGITAL PERSONA OF THE QUICK, THE DEAD AND THE IMAGINARY By JosephJ. Beard' ABSTRACT This article explores a developing technology-the creation of digi- tal replicas of individuals, both living and dead, as well as the creation of totally imaginary humans. The article examines the various laws, includ- ing copyright, sui generis, right of publicity and trademark, that may be employed to prevent the creation, duplication and exploitation of digital replicas of individuals as well as to prevent unauthorized alteration of ex- isting images of a person. With respect to totally imaginary digital hu- mans, the article addresses the issue of whether such virtual humans should be treated like real humans or simply as highly sophisticated forms of animated cartoon characters. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN TR O DU C T IO N ................................................................................................ 1166 II. CLONES: DIGITAL REPLICAS OF LIVING INDIVIDUALS ........................ 1171 A. Preventing the Unauthorized Creation or Duplication of a Digital Clone ...1171 1. PhysicalAppearance ............................................................................ 1172 a) The D irect A pproach ...................................................................... 1172 i) The T echnology ....................................................................... 1172 ii) Copyright ................................................................................. 1176 iii) Sui generis Protection -

Why Call Them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960S Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK

Why Call them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960s Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK Preface In response to the recent increased prominence of studies of "cult movies" in academic circles, this essay aims to question the critical usefulness of that term, indeed the very notion of "cult" as a way of talking about cultural practice in general. My intention is to inject a note of caution into that current discourse in Film Studies which valorizes and celebrates "cult movies" in particular, and "cult" in general, by arguing that "cult" is a negative symptom of, rather than a positive response to, the social, cultural, and cinematic conditions in which we live today. The essay consists of two parts: firstly, a general critique of recent "cult movies" criticism; and, secondly, a specific critique of the term "cult movies" as it is sometimes applied to 1960s American independent biker movies -- particularly films by Roger Corman such as The Wild Angels (1966) and The Trip (1967), by Richard Rush such as Hell's Angels on Wheels (1967), The Savage Seven, and Psych-Out (both 1968), and, most famously, Easy Rider (1969) directed by Dennis Hopper. Of course, no-one would want to suggest that it is not acceptable to be a "fan" of movies which have attracted the label "cult". But this essay begins from a position which assumes that the business of Film Studies should be to view films of all types as profoundly and positively "political", in the sense in which Fredric Jameson uses that adjective in his argument that all culture and every cultural object is most fruitfully and meaningfully understood as an articulation of the "political unconscious" of the social and historical context in which it originates, an understanding achieved through "the unmasking of cultural artifacts as socially symbolic acts" (Jameson, 1989: 20). -

THE PRICE IS RIGHT! He Could Lure You In, and Once Interviewed Him Onstage About His Career, and He Did He Had You for Life

came to town, we were first Rally Convention, Price was the only one of in line to see it and couldn’t the biggies I have ever seen in person. wait for what horrible deaths Unfortunately, he was in frail health, awaited his enemies this time. and the fans never got to speak to him or That was the magic of Price, get autographs. However, director Joe Dante THE PRICE IS RIGHT! he could lure you in, and once interviewed him onstage about his career, and he did he had you for life. the captive audience absorbed everything he Years later, after leav- had to say. As I was, I’m sure they were all ing the horror genre behind pinching themselves to see if it was real. That for girls and the Air Force, I evening with Vincent Price is one of the fond- found myself attracted again est memories I have, and dear Vincent will to all things horror-related. always hold a very special place in my heart. It was then that I started at- 2011 marked the 100th anniversary of tending horror conventions. Vincent Price’s birth, or as it’s been affection- The second show I went to ately referred to, the Vincentennial. A huge was the Fangoria Weekend celebration was given in May in his birth- of Horrors Convention in place of St. Louis; unfortunately, I couldn’t Los Angeles in May 1990. attend. So I decided to honor him within the One of the main attractions pages of Monsters from the Vault. of that convention was that As I did to celebrate the 75th anniversary A Vincent Price was going to be of my favorite film, The Bride of Frankenstein a special guest. -

The Horror Film Series

Ihe Museum of Modern Art No. 11 jest 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart Saturday, February 6, I965 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The Museum of Modern Art Film Library will present THE HORROR FILM, a series of 20 films, from February 7 through April, 18. Selected by Arthur L. Mayer, the series is planned as a representative sampling, not a comprehensive survey, of the horror genre. The pictures range from the early German fantasies and legends, THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI (I9I9), NOSFERATU (1922), to the recent Roger Corman-Vincent Price British series of adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe, represented here by THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH (I96IO. Milestones of American horror films, the Universal series in the 1950s, include THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1925), FRANKENSTEIN (1951), his BRIDE (l$55), his SON (1929), and THE MUMMY (1953). The resurgence of the horror film in the 1940s, as seen in a series produced by Val Lewton at RR0, is represented by THE CAT PEOPLE (19^), THE CURSE OF THE CAT PEOPLE (19^4), I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE (19*£), and THE BODY SNAT0HER (19^5). Richard Griffith, Director of the Film Library, and Mr. Mayer, in their book, The Movies, state that "In true horror films, the archcriminal becomes the archfiend the first and greatest of whom was undoubtedly Lon Chaney. ...The year Lon Chaney died [1951], his director, Tod Browning,filmed DRACULA and therewith launched the full vogue of horror films. What made DRACULA a turning-point was that it did not attempt to explain away its tale of vampirism and supernatural horrors. -

A Cinema of Confrontation

A CINEMA OF CONFRONTATION: USING A MATERIAL-SEMIOTIC APPROACH TO BETTER ACCOUNT FOR THE HISTORY AND THEORIZATION OF 1970S INDEPENDENT AMERICAN HORROR _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by COURT MONTGOMERY Dr. Nancy West, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2015 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled A CINEMA OF CONFRONTATION: USING A MATERIAL-SEMIOTIC APPROACH TO BETTER ACCOUNT FOR THE HISTORY AND THEORIZATION OF 1970S INDEPENDENT AMERICAN HORROR presented by Court Montgomery, a candidate for the degree of master of English, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _________________________________ Professor Nancy West _________________________________ Professor Joanna Hearne _________________________________ Professor Roger F. Cook ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my committee chair, Dr. Nancy West, for her endless enthusiasm, continued encouragement, and excellent feedback throughout the drafting process and beyond. The final version of this thesis and my defense of it were made possible by Dr. West’s critique. I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Joanna Hearne and Dr. Roger F. Cook, for their insights and thought-provoking questions and comments during my thesis defense. That experience renewed my appreciation for the ongoing conversations between scholars and how such conversations can lead to novel insights and new directions in research. In addition, I would like to thank Victoria Thorp, the Graduate Studies Secretary for the Department of English, for her invaluable assistance with navigating the administrative process of my thesis writing and defense, as well as Dr. -

Annual Ccc Off to a Racing Start See Calender on Page 3

Mlbur Cross Library Storrs, Ct, 0*2** donnrrltnttVr. Schmrnelphen* ifotlg (UmpttB Serving Storrs Since 1896 VOL. LXIX NO. 96 STORRS, CONNECTICUT Monday, April 10, 1972 annual ccc off to a racing start See calender on page 3. YERTLE TURTLE: Sally Armstead, a fourth semester physical therapy student, enters herself in the unlimited size division of the New England Invitational Turtle Tournament to be held at 2:00 p.m., Saturday. "Daily Campus" photographer Barry Rimler captures Sally in parts of her training session for the weekend races. President Homer D. Babbidge was the first official sponsor to enter a turtle, "The Search Committee," in the tourney, which is helping to promote funds for the annual Campus Community Carnival. j 1 y1 s bond urges student action goodwin task force report to change 'racist9 systems recommends credit reform Julian Bond appeared before 1300 people in the Many students are unaware of procedures they can use Jorgensen Inner Auditorium, Saturday night, and urged to cut course time, according to Assistant Provost Galvin students to be socially aware and more active politically. Gall. The Goodwin Task Force (The President's The former state representative from Georgia used jokes Committee on Long • Range Financial Planning) has called and anecdotes in illustrating various points. 1 He referred for the extension of these procedures, which include to Richard Nixon as "the bear" and called George Wallace course credit by examination, College Level Examination a "Hillbilly Hitler." Bond also elaborated on the busing Program, and transfer credit from state community issue and called for a "left of center" movement in this colleges. -

The Birth of Haptic Cinema

The Birth of Haptic Cinema An Interactive Qualifying Project Submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by Panhavuth Lau Jordan Stoessel Date: May 21, 2020 Advisor: Brian Moriarty IMGD Professor of Practice Abstract This project examines the history of The Tingler (1959), the first motion picture to incorporate haptic (tactile) sensations. It surveys the career of its director, William Castle, a legendary Hollywood huckster famous for his use of gimmicks to attract audiences to his low- budget horror films. Our particular focus is Percepto!, the simple but effective gimmick created for The Tingler to deliver physical “shocks” to viewers. The operation, deployment and promotion of Percepto! are explored in detail, based on recently-discovered documents provided to exhibitors by Columbia Pictures, the film’s distributor. We conclude with a proposal for a method of recreating Percepto! for contemporary audiences using Web technologies and smartphones. i Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... i Contents ........................................................................................................................................ ii 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 2. William Castle .......................................................................................................................... -

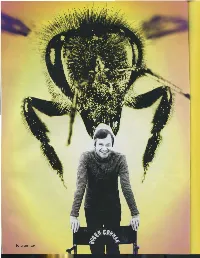

30 MENTAL FLOSS • HOW ROGER CORMAN REVOLUTIONIZED Cl EMA by IAN LENDLER

30 MENTAL_FLOSS • HOW ROGER CORMAN REVOLUTIONIZED Cl EMA BY IAN LENDLER MENTALFLOSS.COM 31 the Golden Age of Hollywood, big-budget movies were classy affairs, full of artful scripts and classically trained actors. And boy, were they dull. Then came Roger Corman, the King of the B-Movies. With Corman behind the camera, motorcycle gangs and mutant sea creatures .filled the silver screen. And just like that, movies became a lot more fun. .,_ Escape from Detroit For someone who devoted his entire life to creating lurid films, you'd expect Roger Corman's biography to be the stuff of tab loid legend. But in reality, he was a straight-laced workaholic. Having produced more than 300 films and directed more than 50, Corman's mantra was simple: Make it fast and make it cheap. And certainly, his dizzying pace and eye for the bottom line paid off. Today, Corman is hailed as one of the world's most prolific and successful filmmakers. But Roger Corman didn't always want to be a director. Growing up in Detroit in the 1920s, he aspired to become an engineer like his father. Then, at age 14, his ambitions took a turn when his family moved to Los Angeles. Corman began attending Beverly Hills High, where Hollywood gossip was a natural part of the lunchroom chatter. Although the film world piqued his interest Corman stuck to his plan. He dutifully went to Stanford and earned a degree in engineering, which he didn't particularly want. Then he dutifully entered the Navy for three years, which he didn't particularly enjoy. -

How I Became the Los Angeles Correspondent for Cahiers Du Cinéma

1 How I Became the Los Angeles Correspondent for Cahiers du cinéma grew up in a small town in North Texas on the Oklahoma border. Living in a big house on the edge of town, I had access to the larger I world through radio—still in its “Golden Age”—and television: The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet (1952), which I still enjoy in reruns; I Love Lucy (1951); the many Warner Bros. television series; and countless westerns, a staple in theaters that filled the airwaves as well. Every week on Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955), which began airing when I was ten, the maestro personally presented concentrated doses of his trademark cinema of suspense and black comedy, while Rod Serling did the same thing on The Twilight Zone (1959), a weekly series that began airing five years later, offering tales of fantasy and science fiction introduced and narrated by Serling. I first encountered Orson Welles inThe Fountain of Youth (1958), an unsold pilot that aired on CBS in 1958 and won a Peabody Award. (I would later introduce it to French audiences via the Cahiers du cinéma when Welles was receiving an honor for his life’s work in France, accompanied by an interview conducted over the telephone between Los Angeles and New York for a special issue of the Cahiers.) The fundamentals of auteurism, a theory promulgated by the Cahiers, were already being communicated to me and future friends in other parts of the country, some of whom grew up to be auteurs of cinema and television: Joe Dante, John Landis, and in a more modest way me, 3 © 2020 State University of New York Press, Albany 4 Letters from Hollywood when editor Ed Marx and I finished a film for Welles in 1994, theFour Men on a Raft section of It’s All True (1943), a three-part film he shot in Latin America in 1942 and was not permitted to finish. -

List of Shows Master Collection

Classic TV Shows 1950sTvShowOpenings\ AdventureStory\ AllInTheFamily\ AManCalledShenandoah\ AManCalledSloane\ Andromeda\ ATouchOfFrost\ BenCasey\ BeverlyHillbillies\ Bewitched\ Bickersons\ BigTown\ BigValley\ BingCrosbyShow\ BlackSaddle\ Blade\ Bonanza\ BorisKarloffsThriller\ BostonBlackie\ Branded\ BrideAndGroom\ BritishDetectiveMiniSeries\ BritishShows\ BroadcastHouse\ BroadwayOpenHouse\ BrokenArrow\ BuffaloBillJr\ BulldogDrummond\ BurkesLaw\ BurnsAndAllenShow\ ByPopularDemand\ CamelNewsCaravan\ CanadianTV\ CandidCamera\ Cannonball\ CaptainGallantOfTheForeignLegion\ CaptainMidnight\ captainVideo\ CaptainZ-Ro\ Car54WhereAreYou\ Cartoons\ Casablanca\ CaseyJones\ CavalcadeOfAmerica\ CavalcadeOfStars\ ChanceOfALifetime\ CheckMate\ ChesterfieldSoundOff\ ChesterfieldSupperClub\ Chopsticks\ ChroniclesOfNarnia\ CimmarronStrip\ CircusMixedNuts\ CiscoKid\ CityBeneathTheSea\ Climax\ Code3\ CokeTime\ ColgateSummerComedyHour\ ColonelMarchOfScotlandYard-British\ Combat\ Commercials50sAnd60s\ CoronationStreet\ Counterpoint\ Counterspy\ CourtOfLastResort\ CowboyG-Men\ CowboyInAfrica\ Crossroads\ DaddyO\ DadsArmy\ DangerMan-S1\ DangerManSeason2-3\ DangerousAssignment\ DanielBoone\ DarkShadows\ DateWithTheAngles\ DavyCrockett\ DeathValleyDays\ Decoy\ DemonWithAGlassHand\ DennisOKeefeShow\ DennisTheMenace\ DiagnosisUnknown\ DickTracy\ DickVanDykeShow\ DingDongSchool\ DobieGillis\ DorothyCollins\ DoYouTrustYourWife\ Dragnet\ DrHudsonsSecretJournal\ DrIQ\ DrSyn\ DuffysTavern\ DuPontCavalcadeTheater\ DupontTheater\ DustysTrail\ EdgarWallaceMysteries\ ElfegoBaca\ -

American International Pictures (AIP) Est Une Société De Production Et

American International Pictures (AIP) est une société de production et distribution américaine, fondée en 1956 depuis "American Releasing Corporation" (en 1955) par James H. Nicholson et Samuel Z. Arkoff, dédiée à la production de films indépendants à petits budgets, principalement à destination des adolescents des années 50, 60 et 70. 1 Né à Fort Dodge, Iowa à une famille juive russe, Arkoff a d'abord étudié pour être avocat. Il va s’associer avec James H. Nicholson et le producteur-réalisateur Roger Corman, avec lesquels il produira dix-huit films. Dans les années 1950, lui et Nicholson fondent l'American Releasing Corporation, qui deviendra plus tard plus connue sous le nom American International Pictures et qui produira plus de 125 films avant la disparition de l'entreprise dans les années 1980. Ces films étaient pour la plupart à faible budget, avec une production achevée en quelques jours. Arkoff est également crédité du début de genres cinématographiques, comme le Parti Beach et les films de motards, enfin sa société jouera un rôle important pour amener le film d'horreur à un niveau important avec Blacula, I Was a Teenage Werewolf et Le Chose à deux têtes. American International Pictures films engage très souvent de grands acteurs dans les rôles principaux, tels que Boris Karloff, Elsa Lanchester et Vincent Price, ainsi que des étoiles montantes qui, plus tard deviendront très connus comme Don Johnson, Nick Nolte, Diane Ladd, et Jack Nicholson. Un certain nombre d'acteurs rejetées ou 2 négligées par Hollywood dans les années 1960 et 1970, comme Bruce Dern et Dennis Hopper, trouvent du travail dans une ou plusieurs productions d’Arkoff.