Visitor Satisfactions, Impact Perceptions and Attitudes Toward Management Options on the Heaphy Track / Gordon Cessford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canoeist Satisfactions, Impact Perceptions, and Attitudes Toward

41 42 ATTACHED QUESTIONNAIRE RESPONSES These responses are presented here as they do not fit the questionnaire format used for this appendix. A. Question 1. Nationality breakdown B. Question 1. Nights on trip and at huts/camps (1) Trip Duration No. of nights 1 nights 2 nights 3 nights 4 nights 5+ nights % trips of this duration 1 9 21 43 26 (ii) Nights at Huts and/or Campsites Overnight accomodation Huts Hut & Multiple Camps Camps only 1 camp huts/camps & 1 but only trips 5 5 12 10 60 C. Question 3. Locations of crowding focus Overall, 59% of visitors (n = 325) considered some places on the visit were more crowded than others. They were asked to indicate in general terms whether this occurred in huts, at campsites, on the track or elsewhere, and then relative to these, specifically where. These specific responses are summarised here. Note that multiple responses were allowed for. Huts - 194 specified huts as a focus of crowding (60% of 325). Of these, the specific focus responses highlighted the following main sites: 71% - John Coull Hut 13% - Tieke Hut/Marae 8% - Whakahoro Hut 43 Campsites - 137 specified campsites as a focus of crowding (42% of 325). Of these, the specific focus responses highlighted the following main sites: 43% - Mangapurua campsites 12% - Ngaporo campsites 11% - Ohinepa campsites On the river - 21 specified areas along the track as a focus of crowding (6% of 325). Of these, no particular areas were prominent. Other - 11 specified `other' as a focus of crowding (3% of 325). Of these, no particular areas were prominent. -

Tramping in New Zealand Tracks and Huts Throughout the Country

For the hard-working Department of Conservation staff who maintain TRAMPING IN NEW ZEALAND tracks and huts throughout the country. A GUIDE TO 40 OF NEW ZEALAND’S BEST TRACKS Text and photographs by Shaun Barnett Maps by Roger Smith, Geographx AckNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank a number of people who have been great companions in the hills: Daryl Ball, David Barnes, Angela Barnett, Grant Barnett, Rob Brown, Dave Chowdhury, Andy Dennis, John Fitzgerald, Tony Gates, Dave Hansford, Debbie Hoare, Andrew Lynch, Ken MacIver, Chris Maclean, Darryn Pegram, Bruce Postill, Andy Reisinger, John Skilton, Mark Stanton and Tom Stanton-Barnett. A number of Department of Conservation (DOC) staff have helped check draft chapters for which I am grate- ful: Wayne Boness, Maurice Bootherstone, Peter Carter, Dale Chittenden, Brendon Clough, Fiona Colquhoun, Paul Davidson, Eric de Boer, Peter Devlin, Olivia Dovey, Jock Edmondson, Owen Graham, Ronan Grew, Roy Grose, Claudia Hill, Vanessa Hooker, Stephen Hormann, Sally Jones, Cal Jose, Ross Kerr, Pete Morton, Mark Nelson, Sharon Pascoe, Sue Scott, Annette Smith, Pat Sheridan, Rudy Tetteroo, Dave Thompson, Mark Townsend, Katrina First published in 2006 by Craig Potton Publishing Upperton, Matt Ward, Dave Waters, Jim Wilson, Don Wood- cock, John Wotherspoon and Tom Young. Reprinted 2007, 2008, 2010 The many pamphlets which DOC produces on various tracks also proved to be excellent sources of information. Craig Potton Publishing 98 Vickerman Street, PO Box 555, Nelson, New Zealand It goes without saying that any mistakes are mine alone: www.craigpotton.co.nz if you find a significant error, write to the publisher, as I’d appreciate knowing about it for future editions. -

Tongariro Northern Circuit Brochure

TONGARIRO NORTHERN CIRCUIT Duration: 3 – 4 days Great Walks season: Distance: 45 km (loop) 20 October 2017 – 30 April 2018 TONGARIRO ELEVATION PROFILE & TRACK GUIDE Oturere NORTHERN 1800 m 26 bunks 7 campsites CIRCUIT 1600 m Mangatepopo 20 bunks 7 campsites 1400 m From alpine herbfields to forests, Whakapapa Village and tranquil lakes to desert-like 1200 m plateaux, you’ll journey through 1100 m a landscape of stark contrasts 9.4 km / 4 hr 12 km / 5 hr with amazing views at every turn in this dual World Heritage site. Winding its way past Mount Tongariro and Mount Ngauruhoe, you will be dazzled on this circuit by dramatic volcanic landscapes and New Zealand’s rich geological and ancestral past. To the north is Lake Taupo, to the east the rugged Kaimanawa Day 1: Whakapapa Village Day 2: Mangatepopo Hut to range. On a clear day you may to Mangatepopo Hut Oturere Hut even catch a glimpse of Mount Taranaki on the west coast. 4 hours, 9.4 km 5 hours, 12 km The Tongariro Northern Circuit can be Your journey begins by making You join the popular Tongariro Alpine your way across the eroded Crossing on the second day, crossing walked in either direction. The track is plains of the Tongariro volcanic remnants of lava flows and climbing well marked and signposted, but some complex, a series of explosion steeply up Te Arawhata to the expansive sections may be steep, rough or muddy. craters and volcanic cones and Red Crater. Here you’ll be dazzled by This guide describes a 4-day clockwise peaks. -

Visitor Satisfactions, Impact Perceptions and Attitudes Toward

Visitor satisfactions, impact perceptions, and attitudes toward management options on the Milford Track SCIENCE FOR CONSERVATION: 87 Gordon Cessford Published by Department of Conservation P.O. Box 10-420 Wellington, New Zealand Great Walks visitor research programme This report is the eighth from the Great Walks visitor research programme. Reports from other track samples are published through the same series. While data were collected predominantly during January–February 1994, those visitor responses still provide valid indications of visit experiences and evaluations. Any significant management or use-pattern changes since then can be interpreted in light of these results. The main change that has occurred on the Milford Track has been the removal of the Clinton Forks Hut and a construction of a new hut on a site further down-river. Science for Conservation presents the results of investigations by DoC staff, and by contracted science providers outside the Department of Conservation. Publications in this series are internally and externally peer reviewed. © June 1998, Department of Conservation ISSN 1173–2946 ISBN 0–478–21729–3 This publication originated from work done under Department of Conservation Investigation no. 1758, carried out by Gordon Cessford, Science and Research Division, Department of Conservation. It was approved for publication by the Director, Science and Research Division, Science Technology & Information Services, Department of Conservation, Wellington. Cataloguing in Publication Cessford, Gordon R. (Gordon Robert), 1962– Visitor satisfactions, impact perceptions, and attitudes toward management options on the Milford Track / Gordon Cessford. Wellington, N.Z. : Dept. of Conservation, 1998. 1 v. ; 30 cm. (Science for conservation, 1173–2946 ; 87.) ISBN 0478217293 1. -

Exploring Parks

World Heritage Areas More information New Zealand has three world heritage areas: Tongariro National Care for the environment Park, South-West New Zealand - Te Wähipounamu, and the Toitu te whenua Exploring subantarctic islands of Antipodes, Auckland, Enderby, • Respect natural and cultural heritage Campbell, Bounty, and Snares. Four National Parks • Care for plants, animals and historic relics lie within Te Wähipounamu: Westland / Tai Poutini, • Keep waterways clean Parks Fiordland, Aoraki / Mount Cook and Mount Aspiring. • Keep your equipment clean to avoid spreading Tour operators visit the subantarctic islands. weeds and diseases NEW ZEALAND FREE • Take all your rubbish with you • Use toilets provided • Light fires only where permitted • Stay on tracks. Camp carefully • Share the outdoors. Be considerate of others Sea lions, Auckland Island. DOC Pleurophyllum speciosum, Campbell Island. DOC Tuatara, Great Barrier Is. Historic heritage Craig Potten Taonga - Mäori Heritage Visitor Centres Many places within Aotearoa (New Zealand) are considered by DOC visitor centres have a wealth of detailed Mäori as taonga (treasures). They represent the identity, spirit recreation and conservation information and and history of Mäori ancestors. DOC and Mäori work together to friendly, helpful staff. protect these special places. For non-DOC bookings, transport or accommod- Historic places ation contact any i-site information centre. New Zealand’s historic heritage is rich with remains of Mäori Security pä sites, battle sites, historic settlements and Theft from vehicles happens. Don’t make it easy for thieves, museums house treasured relics of past times. remember to lock your vehicle and take valuables with you. Many railway and gold mining heritage sites are Feedback preserved as walking tracks, often with tunnels, Feedback about this brochure is welcome: [email protected] bridges and other evidence of engineering achievement. -

Routeburn Track

ROUTEBURN TRACK Great Walks season: Duration: 2 – 4 days 24 October 2017 – Distance: 32 km (one way) 30 April 2018 ELEVATION PROFILE & TRACK GUIDE ROUTEBURN Harris Saddle TRACK 1250 m Routeburn Falls 48 bunks The Routeburn Track is the Routeburn Flats 1000 m 20 bunks ultimate alpine adventure, taking 15 campsites you through ice-carved valleys 750 m Routeburn and below the majestic peaks of Shelter the Southern Alps/Kā Tiritiri o te Moana. 500 m A short trip from bustling 6.5 km / 1.5 – 2.5 hrs 2.3 km / 1–1.5 hrs Queenstown, this Great Walk links Mount Aspiring and Fiordland National Parks in the Te Wāhipounamu – South West New Zealand World Heritage Area. Weaving through meadows, reflective tarns and alpine gardens, you’ll be rewarded with spectacular vistas over vast mountain ranges and valleys. Day 1: Routeburn Shelter to Routeburn Falls Hut The Routeburn Track can be walked in either direction. The track is well marked and signposted, but some 3 hours – 4 hours, 8.8 km sections are steep and rough and The track begins at Routeburn Shelter, gently winding alongside may be muddy and slippery. Poor the crystal-clear Route Burn (river). After passing Sugarloaf Stream, weather conditions can make this you’ll climb to Bridal Veil Waterfall and continue above the gorge. walk challenging, even in the Great A swing bridge leads to open grassed flats, and the Routeburn Flats Walks season. Hut and Campsite. The track climbs steadily through stunning beech forest, providing views of the Humboldt Mountains. End the This guide describes a 3-day easy hike day at Routeburn Falls Hut, on the edge of the bushline and close to the impressive Routeburn Falls cascade. -

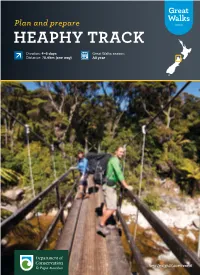

Heaphy Track

Plan and prepare HEAPHY TRACK Duration: 4–6 days Great Walks season: Distance: 78.4 km (one way) All year ELEVATION PROFILE & TRACK GUIDE HEAPHY Perry Saddle Hut 28 bunks 10 campers Gouland Aorere Shelter Downs Hut 1000 m TRACK 10 campers 8 bunks 10 campers If it’s varied and rugged 750 m landscapes with mountain views Brown Hut you’re looking for, you’ll be spoilt 500 m 16 bunks for choice on the Heaphy Track. 20 campers 250 m Retrace the steps of early Māori seeking pounamu (greenstone) 0 m and 19th century gold prospectors. 17.5 km / 5 hrs 7 km / 2 hrs 5.4 km / 1.5 hrs You’ll pass through expansive tussock downs, lush forests and nīkau palms before reaching the roaring seas of the West Coast. Tackle the track in 4 or 5 days, or take your time and soak up the views over 6 days. There is a popular 2-day, overnight return trip on the western side from Kōhaihai to Heaphy Hut. You can also mountain bike the track Day 1: Brown Hut to Perry during the mountain biking Saddle Hut season and it is a 2–3 day ride. 5 hours, 17.5 km The Heaphy Track in Kahurangi As you wind your way through bush National Park can be walked in either you’ll climb gradually, following a route direction. The track is well marked and once surveyed for a road. It’s 4 hours signposted, but some sections may be to Aorere Shelter, which affords views steep and rough and the track could of Aorere valley and, on clear days, Mount Taranaki/Egmont. -

Milford Track

MILFORD TRACK Duration: 4 days Distance: 53.5 km (one way) Great Walks season: 24 October 2017 – 30 April 2018 MILFORD ELEVATION PROFILE & TRACK GUIDE TRACK 1000 m Experience the ‘finest walk in 750 m the world’ as you retrace the steps Prairie Bus Shelter Stop of early explorers on the world- 500 m Clinton Hut renowned Milford Track. 40 bunks Glade Take a journey along valleys carved 250 m Wharf by glaciers, wander through ancient rainforests and admire cascading 0 m waterfalls. You’ll follow a historic 5 km / 1 –1.5 hrs 16.5 km / 6 hrs route through Fiordland National Park, part of Te Wāhipounamu – South West New Zealand World Heritage Area, before reaching your final destination, the spectacular Milford Sound/Piopiotahi. The Milford Track can only be walked in one direction. The track is well marked and signposted, but some Day 1: Glade sections are steep and rough and the Wharf to track may be muddy and slippery. Clinton Hut Day 2: Clinton Hut to Mintaro Hut Poor weather conditions can make this walk challenging, even in the Great 1 hour – 1 hour 6 hours, 16.5 km 30 minutes, 5 km Walks season. A gradual climb follows the Clinton After a boat cruise from River to its source, Lake Mintaro, at This guide describes a 4-day hike for Te Anau Downs (1 hour the base of the renowned Mackinnon independent, non-guided walkers from 15 minutes), take a leisurely Pass. Past Hirere Falls you will get the head of Lake Te Anau to Sandfly Point walk through beautiful your first view of Mackinnon Pass in Milford Sound/Piopiotahi during the beech forest along the and the impressive Pompolona ice Great Walks season (24 October 2017 banks of the Clinton River field. -

New Zealand's Most Spectacular Walks

Roys Peak Track, Wanaka newzealand.com NEW ZEALAND’S MOST SPECTACULAR WALKS WALKING IN NEW ZEALAND CHOOSING A TRAIL terrain and are suitable for people of all abilities, with some accessible to New Zealand’s well-established and maintained wheelchairs or strollers. At the other end trail network offers a remarkably diverse array of the scale, expert trails follow challenging of hikes for every ability and interest. The routes through often steep and rocky majority can be found in New Zealand’s 13 backcountry requiring total self-sufficiency national parks and countless other reserves and extensive hiking experience. managed by the Department of Conservation (DOC), although scores of regional parks Tourism New Zealand’s website is a great and recreational areas, managed by local place to start (newzealand.com), with greater detail provided by the Department of councils, offer even more trails. Conservation (doc.govt.nz). On the ground, Most tracks are officially graded from easiest to i-SITE visitor information centres provide expert, making it simple to select a walk that’s excellent advice from locals who know their right for you. Those graded easiest follow flat own back yards. Bream Head, Northland IMMERSE YOURSELF IN A NATURAL WONDERLAND SHORT WALKS & DAY HIKES MANAAKI TRAILS If there’s a special place A core Māori value that to visit or something encapsulates the spirit of Imagine a holiday where one journey leads to another, taking you to remarkable to see, you can looking after manuhiri (visitors), unforgettable places, full of incredible sights. be sure that there’s a Short Walk or Day Hike manaakitanga underpins a series of special that’ll take you there. -

Great Walks of New Zealand

media release media release media release GREAT WALKS OF NEW ZEALAND A practical and visually spectacular tribute to some of the finest walking tracks in the world Great Walks of New Zealand is a tribute to New Zealand’s eight finest walking tracks, by renowned wilderness photographer Craig Potton. Based on the best-selling Classic Walks of New Zealand, this book has been updated and revised to focus on our Great Walks, a reflection of the international prominence these tracks now rightly enjoy. Tracks included are Stewart Island’s Rakiura Track, the Kepler Track, the Milford Track, the Routeburn Track, the Heaphy Track, the Abel Tasman Coast Track, the Tongariro Northern Circuit Great Walk, and the Lake Waikaremona Track in Te Urewera. With 3D overview maps from Geographx and up-to-date track information, Great Walks of New Zealand combines words and photographs to rekindle memories of past trips, and to inspire readers to new experiences on these magnificent tracks. ABOUT THE AUTHOR CRAIG POTTON is one of New Zealand’s best known landscape photographers, and a noted conservationist. He is the author of many New Zealand books, including the best-selling New Zealand Aotearoa, Lost in New Zealand, New Zealand’s Wilderness Heritage (with Les Molloy), and Craig Potton New Zealand. Craig’s profile has increased over recent years, as he has established himself as a TV presenter, with two documentary series on wild rivers and wild coasts screening on prime- time television to widespread acclaim. $49.99 230 x 280 mm, 120 pp, hardback PLC with dustjacket, colour photographs throughout ISBN: 978 1 927213 63 6 Published: October 2015 For more information contact Raewyn Davies, freelance book publicist PHONE 027 425 7768 EMAIL [email protected] PHONE +64 3 548 9009 EMAIL [email protected] WEB pottonandburton.co.nz. -

Great Walks Summer Season 2018/19 Booking Data

GREAT WALKS 2018/19 SUMMER SEASON October 2018 to April 2019 Background New Zealand’s Great Walks are premier multi-day tracks (and one river journey) that go through spectacular and diverse landscapes. The tracks are well-formed and have higher standard huts and facilities. International visitor growth and promotion of the Great Walks through DOC’s partnership with Air New Zealand has led to Great Walk bookings greatly increasing in recent years. Through limiting the capacity in bookable huts and camp site space we can manage growth, protect the surrounding environments and maintain a quality experience for visitors on the Great Walks. This is the first season the department has trialled dierential pricing for international visitors. Please note this document reports on bednights booked not actual visitor numbers. It reports on bednights during summer season between October to April. How did DOC managed Great Walks perform overall? For the first time in a Over the summer season, Overall summer NZ bednights New Zealander bednights number of years, New 2018/19 proportion of total bednights have season bednights have increased on all 114,020 27% Zealand visitors utilised bednights by origin decreased (-5%). This is 220,060 5% 2018/19 DOC managed Great % change from more bednights than 52% 48% partly due to the dierential 2018/19 % change from bednights prev. year bednights prev. year Walks. international visitors NZ Intl. pricing trial on four walks. across the Great Walks. Revenue has increased Hut occupancy over the International bednights have International bednights due to: 1) the dierential Overall revenue peak summer period has Peak summer decreased, most notably on occupancy (Dec to Feb) 106,040 26% pricing trial on four walks remained high. -

Guide to For

WANDERLUST inspiration for adventurers Plan, commit, go! Get inspired and start making memories of your own. Kia Ora ..........................................................................................................3 Intro ...............................................................................................................5 History .....................................................................................................................5 Wildlife ....................................................................................................................6 Tramping ..................................................................................................................6 Itinerary .........................................................................................................8 Auckland ..................................................................................................................9 Northland & Bay of Islands ......................................................................................10 Coromandel ............................................................................................................12 Rotorua ..................................................................................................................14 The Bay of Plenty ....................................................................................................15 Tongariro National Park ..........................................................................................17