Self-Determination and Territorial Integrity in the Chagos Advisory Proceedings: Potential Broader Ramifications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country of Citizenship Active Exchange Visitors in 2017

Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 Active Exchange Visitors Country of Citizenship in 2017 AFGHANISTAN 418 ALBANIA 460 ALGERIA 316 ANDORRA 16 ANGOLA 70 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA 29 ARGENTINA 8,428 ARMENIA 325 ARUBA 1 ASHMORE AND CARTIER ISLANDS 1 AUSTRALIA 7,133 AUSTRIA 3,278 AZERBAIJAN 434 BAHAMAS, THE 87 BAHRAIN 135 BANGLADESH 514 BARBADOS 58 BASSAS DA INDIA 1 BELARUS 776 BELGIUM 1,938 BELIZE 55 BENIN 61 BERMUDA 14 BHUTAN 63 BOLIVIA 535 BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 728 BOTSWANA 158 BRAZIL 19,231 BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS 3 BRUNEI 44 BULGARIA 4,996 BURKINA FASO 79 BURMA 348 BURUNDI 32 CAMBODIA 258 CAMEROON 263 CANADA 9,638 CAPE VERDE 16 CAYMAN ISLANDS 1 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC 27 CHAD 32 Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 CHILE 3,284 CHINA 70,240 CHRISTMAS ISLAND 2 CLIPPERTON ISLAND 1 COCOS (KEELING) ISLANDS 3 COLOMBIA 9,749 COMOROS 7 CONGO (BRAZZAVILLE) 37 CONGO (KINSHASA) 95 COSTA RICA 1,424 COTE D'IVOIRE 142 CROATIA 1,119 CUBA 140 CYPRUS 175 CZECH REPUBLIC 4,048 DENMARK 3,707 DJIBOUTI 28 DOMINICA 23 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 4,170 ECUADOR 2,803 EGYPT 2,593 EL SALVADOR 463 EQUATORIAL GUINEA 9 ERITREA 10 ESTONIA 601 ETHIOPIA 395 FIJI 88 FINLAND 1,814 FRANCE 21,242 FRENCH GUIANA 1 FRENCH POLYNESIA 25 GABON 19 GAMBIA, THE 32 GAZA STRIP 104 GEORGIA 555 GERMANY 32,636 GHANA 686 GIBRALTAR 25 GREECE 1,295 GREENLAND 1 GRENADA 60 GUATEMALA 361 GUINEA 40 Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 GUINEA‐BISSAU -

Global Scores the Ocean Health Index Team Table of Contents

2015 GLOBAL SCORES THE OCEAN HEALTH INDEX TEAM TABLE OF CONTENTS Conservation International Introduction to Ocean Health Index ............................................................................................................. 1 Results for 2015 ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Country & Territory Scores ........................................................................................................................... 9 Appreciations ............................................................................................................................................. 23 Citation ...................................................................................................................................................... 23 UC Santa Barbara, National Center for Ecological Analysis & Synthesis INTRODUCTION TO THE OCEAN HEALTH INDEX Important note: Scores in this report differ from scores originally posted on the Ocean Health Index website, www.oceanhealthindex.org and shown in previous reports. Each year the Index improves methods and data where possible. Some improvements change scores and rankings. When such changes occur, all earlier scores are recalculated using the new methods so that any differences in scores between years is due to changes in the conditions evaluated, not to changes in methods. This permits year-to-year comparison between all global-level Index results. Only the scores most recently -

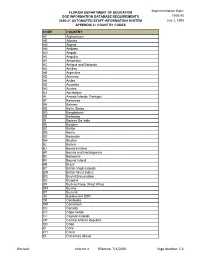

Florida Department of Education

)/25,'$ '(3$570(17 2) ('8&$7,21 ,PSOHPHQWDWLRQ 'DWH '2( ,1)250$7,21 '$7$ %$6( 5(48,5(0(176 )LVFDO <HDU 92/80( , $8720$7(' 678'(17 ,1)250$7,21 6<67(0 July 1, 1995 $8720$7(' 678'(17 '$7$ (/(0(176 APPENDIX G COUNTRY CODES CODE COUNTRY CODE COUNTRY AF Afghanistan CV Cape Verde AB Albania CJ Cayman Islands AG Algeria CP Central African Republic AN Andorra CD Chad AO Angola CI Chile AV Anguilla CH China AY Antarctica KI Christmas Island AC Antigua and Barbuda CN Clipperton Island AX Antilles KG Cocos Islands (Keeling) AE Argentina CL Colombia AD Armenia CQ Comoros AA Aruba CF Congo AS Australia CR Coral Sea Island AU Austria CS Costa Rica AJ Azerbaijan DF Croatia AI Azores Islands, Portugal CU Cuba BF Bahamas DH Curacao Island BA Bahrain CY Cyprus BS Baltic States CX Czechoslovakia BG Bangladesh DT Czech Republic BB Barbados DK Democratic Kampuchea BI Bassas Da India DA Denmark BE Belgium DJ Djibouti BZ Belize DO Dominica BN Benin DR Dominican Republic BD Bermuda EJ East Timor BH Bhutan EC Ecuador BL Bolivia EG Egypt BJ Bonaire Island ES El Salvador BP Bosnia and Herzegovina EN England BC Botswana EA Equatorial Africa BV Bouvet Island EQ Equatorial Guinea BR Brazil ER Eritrea BT British Virgin Islands EE Estonia BW British West Indies ET Ethiopia BQ Brunei Darussalam EU Europa Island BU Bulgaria FA Falkland Islands (Malvinas) BX Burkina Faso, West Africa FO Faroe Islands BM Burma FJ Fiji BY Burundi FI Finland JB Byelorussia SSR FR France CB Cambodia FM France, Metropolitian CM Cameroon FN French Guiana CC Canada FP French Polynesia Revised: -

ISO Country Codes

COUNTRY SHORT NAME DESCRIPTION CODE AD Andorra Principality of Andorra AE United Arab Emirates United Arab Emirates AF Afghanistan The Transitional Islamic State of Afghanistan AG Antigua and Barbuda Antigua and Barbuda (includes Redonda Island) AI Anguilla Anguilla AL Albania Republic of Albania AM Armenia Republic of Armenia Netherlands Antilles (includes Bonaire, Curacao, AN Netherlands Antilles Saba, St. Eustatius, and Southern St. Martin) AO Angola Republic of Angola (includes Cabinda) AQ Antarctica Territory south of 60 degrees south latitude AR Argentina Argentine Republic America Samoa (principal island Tutuila and AS American Samoa includes Swain's Island) AT Austria Republic of Austria Australia (includes Lord Howe Island, Macquarie Islands, Ashmore Islands and Cartier Island, and Coral Sea Islands are Australian external AU Australia territories) AW Aruba Aruba AX Aland Islands Aland Islands AZ Azerbaijan Republic of Azerbaijan BA Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina BB Barbados Barbados BD Bangladesh People's Republic of Bangladesh BE Belgium Kingdom of Belgium BF Burkina Faso Burkina Faso BG Bulgaria Republic of Bulgaria BH Bahrain Kingdom of Bahrain BI Burundi Republic of Burundi BJ Benin Republic of Benin BL Saint Barthelemy Saint Barthelemy BM Bermuda Bermuda BN Brunei Darussalam Brunei Darussalam BO Bolivia Republic of Bolivia Federative Republic of Brazil (includes Fernando de Noronha Island, Martim Vaz Islands, and BR Brazil Trindade Island) BS Bahamas Commonwealth of the Bahamas BT Bhutan Kingdom of Bhutan -

Conflict About Scattered Islands in the Indian Ocean

Sentinel Vision EVT-699 Conflict about Scattered Islands in the Indian Ocean 23 July 2020 Sentinel-1 CSAR SM acquired on 08 December 2014 at 15:41:52 UTC Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 24 September 2018 at 14:54:32 UTC ... Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 30 March 2020 at 06:43:41 UTC Author(s): Sentinel Vision team, VisioTerra, France - [email protected] 2D Layerstack Keyword(s): Archipelago, national park, biodiversity, atoll, coral reef, lagoon, mangrove, fishing, oil, France, Madagascar Fig. 1 - S1 - Location of the Scattered Islands in the Indian Ocean. 2D view Fig. 2 - S2 (14.02.2020) - Europa Island, it encompasses a lagoon and a mangrove forest. 2D view / The Scattered Islands in the Indian Ocean consist of four small coral islands, an atoll, and a reef in the Indian Ocean. It is administrated by France though sovereignty over some or all of the Islands is contested by Madagascar, Mauritius, and the Comoros. None of the islands has ever had a permanent population. Fig. 3 - S1 (08.12.2014) - Europa Island at high tide. It is the southernmost island of the group. 2D view In Madagascar, the question of national sovereignty remains sensitive in public opinion. Especially when it comes to litigation with the former colonial power. The claim of the Scattered Islands is therefore the subject of a broad consensus. French side, even if the subject is more unknown, however, there has always been reluctance to give up any territory whatsoever. In a similar case, the co-management agreement of Tromelin Island with Mauritius, dated 2010, is still blocked in the National Assembly. -

Îles Eparses One of the World’S Largest Lagoons

EU OVERSEAS REGIONS OF GLOBAL With the kind support of: 7IMPORTANCE Indian Did you Indian Ocean Ocean know? Mayotte is surrounded by a double coral reef barrier - a very rare phenomenon – sheltering Îles Eparses one of the world’s largest lagoons. - Grande The Indian Ocean is home to geologically Glorieuse and biologically extremely diverse Réunion Island hosts a UNESCO world islands belonging to four European heritage site covering about 40% of the © Stéphanie Légeron Overseas entities: the two French island’s surface. overseas departments, Mayotte and Europa – a coral island of the French Îles Réunion Island, the French Îles Éparses Eparses (Scattered Islands) - is one of the (Scattered Islands) and the British Indian world’s most important nesting grounds for Ocean Territory (BIOT). the Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas): 8,000 to 15,000 females lay their eggs on the island The steep volcanic terrain of Réunion each year. Island hosts a rich altitudinal plant biodiversity that is relatively well The waters of the British Indian Ocean preserved compared to neighbouring Territory (BIOT) are home to the currently largest no-take marine reserve and the islands. Mayotte has a remarkable biggest atoll on Earth, 25% of the Indian diversity of twenty two known marine Ocean’s coral reefs and 6 times more fish mammals and one of the world’s than any other reef system in the region. most dense tropical island floras. The ecosystems of the uninhabited and Réunion Island is one of the most advanced remote islands Îles Eparses and BIOT regions in terms of energy efficiency: In 2008, Réunion launched a project to be entirely are in near pristine condition and a energy self-sufficient by 2030. -

S LA RÉUNION and ILES EPARSES

Important Bird Areas in Africa and associated islands – La Réunion and Iles Eparses ■ LA RÉUNION AND ILES EPARSES MATTHIEU LE CORRE AND ROGER J. SAFFORD Réunion Cuckoo-shrike Coracina newtoni. (ILLUSTRATION: DAVE SHOWLER) GENERAL INTRODUCTION Mauritius is 824 m) and secondly, around the 201 km of coastline, reefs (20 km long) and islets are almost absent. Two very distinct territories, Ile de la Réunion, usually (and The climate is dominated by the south-east trade winds and by henceforth) known as La Réunion, and Iles Eparses, are considered tropical depressions. The mountains, especially in the east, are in this chapter, because they are both French dependencies in the extremely humid, most receiving 2,000–5,000 mm (but locally up Malagasy faunal region, and the latter is administered primarily to 9,000 mm) of rainfall annually; mean annual temperatures are from the former. However, general information is provided below below 16°C over a wide area, with frosts frequent in winter above separately. 2,000 m. For at least part of most days the slopes from around 1,500–2,500 m are shrouded in cloud. The leeward (western) ■ La Réunion lowlands are drier and hotter (less than 2,000 mm rainfall, annual La Réunion is a mountainous island covering 2,512 km² in the mean temperature 23–25°C). The wettest, hottest months are from tropical south-west Indian Ocean. It is the westernmost of the December to April, while September to November are driest, and Mascarene island chain, a volcanic archipelago which includes two June to August are coolest. -

Implementation Date: 1995-95 July 1, 1995 Revised: Volume II Effective: 7

Implementation Date: FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DOE INFORMATION DATABASE REQUIREMENTS 1995-95 2020-21 AUTOMATED STAFF INFORMATION SYSTEM July 1, 1995 APPENDIX C: COUNTRY CODES CODE COUNTRY AF Afghanistan AB Albania AG Algeria AN Andorra AO Angola AV Anguilla AY Antarctica AC Antigua and Barbuda AX Antilles AE Argentina AD Armenia AA Aruba AS Australia AU Austria AJ Azerbaijan AI Azores Islands, Portugal BF Bahamas BA Bahrain BS Baltic States BG Bangladesh BB Barbados BI Bassas Da India BE Belgium BZ Belize BN Benin BD Bermuda BH Bhutan BL Bolivia BJ Bonaire Island BP Bosnia and Herzegovina BC Botswana BV Bouvet Island BR Brazil BT British Virgin Islands BW British West Indies BQ Brunei Darussalam BU Bulgaria BX Burkina Faso, West Africa BM Burma BY Burundi JB Byelorussia SSR CB Cambodia CM Cameroon CC Canada CV Cape Verde CJ Cayman Islands CP Central African Republic CD Chad CI Chile CH China KI Christmas Island Revised: Volume II Effective: 7/1/2020 Page Number: C-1 Implementation Date: FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DOE INFORMATION DATABASE REQUIREMENTS 1995-95 2020-21 AUTOMATED STAFF INFORMATION SYSTEM July 1, 1995 APPENDIX C: COUNTRY CODES CODE COUNTRY CN Clipperton Island KG Cocos Islands (Keeling) CL Colombia CQ Comoros CF Congo CR Coral Sea Island CS Costa Rica DF Croatia CU Cuba DH Curacao Island CY Cyprus CX Czechoslovakia DT Czech Republic DK Democratic Kampuchea DA Denmark DJ Djibouti DO Dominica DR Dominican Republic EJ East Timor EC Ecuador EG Egypt ES El Salvador EN England EA Equatorial Africa EQ Equatorial Guinea -

Des Îles Eparses Tromelin, Glorieuses, Juan De Nova, Europa Et Bassas Da India

Livret de découverte des îles Eparses Tromelin, Glorieuses, Juan de Nova, Europa et Bassas da India LOGOTYPES TAAF 1.a - Le logo avec la Marianne 1.b - Le logo TAAF 1.c - Edition spéciale pour les personnels TAAF 1.d - Version une couleur Terres australes et Terres australes et Terres australes et TAAF TAAF TAAF antarctiques françaises antarctiques françaises antarctiques françaises 1.b’ - Le logo TAAF avec cartouche noir 1.c’ - Edition spéciale avec cartouche noir Terres australes et Terres australes et TAAF TAAF antarctiques françaises antarctiques françaises 2.a - L’archipel de Crozet 2.a’ - L’archipel de Crozet 2.b - L’archipel de Crozet 2.b’ - L’archipel de Crozet Terres australes et antarctiques françaises Terres australes et antarctiques françaises Terres australes et antarctiques françaises Terres australes et antarctiques françaises 46°25’ S TAAF 46°25’ S TAAF 46°25’ S TAAF 46°25’ S TAAF District de Crozet District de Crozet District de Crozet District de Crozet 3.a - L’archipel des Kerguelen 3.a’ - L’archipel des Kerguelen 3.b - L’archipel des Kerguelen 3.b’ - L’archipel des Kerguelen Terres australes et antarctiques françaises Terres australes et antarctiques françaises Terres australes et antarctiques françaises Terres australes et antarctiques françaises 49°21’ S 49°21’ S 49°21’ S 49°21’ S TAAF TAAF TAAF TAAF District de Kerguelen District de Kerguelen District de Kerguelen District de Kerguelen 4.a - Les îles Saint-Paul et Amsterdam 4.a’ - Les îles Saint-Paul et Amsterdam 4.b - Les îles Saint-Paul et Amsterdam 4.b’ - Les -

Attachment 2 International Points - Country Code Listing Alphabetic Order

Attachment 2 International Points - Country Code Listing Alphabetic Order FCC reporting Codes FCC reporting Codes Country Region Country Country Region Country Code Code Code Code Abu Dhabi 3 1 Chad 2 61 Admiralty Islands 8 2 Chagos Archipelago 7 350 Afghanistan 7 3 Chatham Island 8 62 Ajman 3 4 Chile 6 63 Alaska 5 1005 China 7 64 Albania 9 6 Choiseul Island 8 65 Alderney 1 7 Christmas Island 7 362 Algeria 2 8 Cocos (Keeling) Islands 8 67 American Samoa 8 1009 Colombia 6 68 Andaman Islands 7 355 Comoros 2 69 Andorra 1 10 Congo 2 70 Anegada Islands 4 11 Cook Islands 8 71 Angola 2 12 Coral Sea Islands 8 72 Anguilla 4 13 Corsica 1 73 Antarctica 10 14 Costa Rica 5 74 Antigua and Barbuda 4 15 Cote d'Ivoire 2 75 Antipodes Islands 8 356 Croatia 9 76 Argentina 6 16 Cuba 4 77 Armenia 9 17 Curacao 4 78 Aruba 4 18 Cyprus 1 79 Ascension Island 2 19 Czech Republic 9 384 Auckland Islands 8 357 Czechoslovakia (former) 9 80 Australia 8 20 Denmark 1 81 Austria 1 21 Diego Garcia 7 364 Azerbaijan 9 22 Djibouti 2 82 Azores 1 23 Dominica 4 83 Bahamas, The 4 24 Dominican Republic 4 84 Bahrain 3 25 Dubai 3 85 Baker Island 8 1026 Easter Island 6 86 Balearic Islands 1 27 Ecuador 6 87 Bangladesh 7 28 Egypt 2 88 Barbados 4 29 El Salvador 5 89 Barbuda 4 30 England 1 90 Bassas Da India 2 358 Equatorial Guinea 2 91 Belarus 9 50 Eritrea 2 92 Belgium 1 31 Estonia 9 93 Belize 5 32 Ethiopia 2 94 Benin 2 33 Europa Island 2 365 Bequia 4 34 Faeroe Islands 1 95 Bermuda 4 35 Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) 6 96 Bhutan 7 36 Fanning Atoll 8 97 Bolivia 6 37 Fernando de Noronha -

France in the Indian Ocean: a Geopolitical Perspective and Its Implications for Africa

MARCH 2017 POLICY INSIGHTS 42 FRANCE IN THE INDIAN OCEAN: A GEOPOLITICAL PERSPECTIVE AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR AFRICA AGATHE MAUPIN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The world’s oceans have been brought back into focus in recent years. With an estimated economic value of some $2.5 trillion (ZAR 25.9 trillion), oceans collectively constitute the world’s seventh largest economy and hold a tremendous potential for further economic development.1 Today’s growing interest in maritime affairs, within the international community and among policymakers, revives ancient seaborne trade routes and relationships. For emerging economies, attempts to capture a growing share of the oceans’ value will lead into a rekindling of old ties and a shaping of new ‘blue’ partnerships. As it was once a maritime power, France makes a convincing case for the development of new perspectives with former alliances in the Indian Ocean region (IOR). By maintaining French territories in the southern part of the third-largest ocean in the world, France aims to secure an international AUTHOR position on principal maritime lines and grow economically, as well as to preserve, if not expand, its sphere of influence. DR AGATHE MAUPIN is a Senior Research Associate at the SAIIA INTRODUCTION Foreign Policy programme. She has been working on For centuries, the world’s oceans have facilitated interactions among people. South Africa’s water and As illustrated by the maritime empires built by the European powers during the energy policy since 2010. 17th century, oceans offered a significant potential to increase countries’ spheres of influence. Along with Portugal, Spain, Britain and the Netherlands, France was also a kingdom looking to enter into maritime trade routes, which were opened up by crossing the Indian, Atlantic and Pacific oceans. -

List of Country Codes

Country Codes (Alphabetical by Code) Code Geopolitical Entity AA ARUBA AC ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA AE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES AF AFGHANISTAN AG ALGERIA AJ AZERBAIJAN AL ALBANIA AM ARMENIA AN ANDORRA AO ANGOLA AQ AMERICAN SAMOA AR ARGENTINA AS AUSTRALIA AT ASHMORE AND CARTIER ISLANDS AU AUSTRIA AV ANGUILLA AY ANTARCTICA BA BAHRAIN BB BARBADOS BC BOTSWANA BD BERMUDA BE BELGIUM BF BAHAMAS, THE BG BANGLADESH BH BELIZE BK BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA BL BOLIVIA BM BURMA BN BENIN BO BELARUS BP SOLOMON ISLANDS BR BRAZIL BS BASSAS DA INDIA BT BHUTAN BU BULGARIA BV BOUVET ISLAND BX BRUNEI BY BURUNDI CA CANADA CB CAMBODIA CD CHAD CE SRI LANKA CF CONGO CG CONGO CH CHINA CI CHILE CJ CAYMAN ISLANDS CK COCOS (KEELING) ISLANDS CL CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN LINE ISLANDS CM CAMEROON CN COMOROS CO COLOMBIA CQ NORTHERN MARIANAS ISLANDS CR CORAL SEA ISLANDS Country Codes (Alphabetical by Code) Code Geopolitical Entity CS COSTA RICA CT CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC CU CUBA CV CAPE VERDE CW COOK ISLANDS CY CYPRUS CZ CZECHOSLOVAKIA DA DENMARK DJ DJIBOUTI DM DAHOMEY [BENIN] DO DOMINICA DQ JARVIS ISLAND DR DOMINICAN REPUBLIC EB EAST BERLIN EC ECUADOR EG EGYPT EI IRELAND EK EQUATORIAL GUINEA EN ESTONIA EQ CANTON AND ENDERBERRY ISLANDS ER ERITREA ES EL SALVADOR ET ETHIOPIA EU EUROPA ISLAND EZ CZECH REPUBLIC FG FRENCH GUIANA FI FINLAND FJ FIJI FK FALKLAND ISLANDS FM MICRONESIA, FEDERATED STATES OF FO FAROE ISLANDS FP FRENCH POLYNESIA FR FRANCE FS FRENCH SOUTHERN AND ANTARCTIC LANDS FT FRENCH TERRITORY OF THE AFFARS AND ISSAS GA GAMBIA, THE GB GABON GC EAST GERMANY (GERMAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC)