Arterial Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

59 Arterial Catheter Insertion (Assist), Care, and Removal 509

PROCEDURE Arterial Catheter Insertion 59 (Assist), Care, and Removal Hillary Crumlett and Alex Johnson PURPOSE: Arterial catheters are used for continuous monitoring of blood pressure, assessment of cardiovascular effects of vasoactive drugs, and frequent arterial blood gas and laboratory sampling. In addition, arterial catheters provide access to blood samples that support the diagnostics related to oxygen, carbon dioxide, and bicarbonate levels (oxygenation, ventilation, and acid-base status). PREREQUISITE NURSING aortic valve closes, marking the end of ventricular systole. KNOWLEDGE The closure of the aortic valve produces a small rebound wave that creates a notch known as the dicrotic notch. The • Knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the vascu- descending limb of the curve (diastolic downslope) repre- lature and adjacent structures is needed. sents diastole and is characterized by a long declining • Knowledge of the principles of hemodynamic monitoring pressure wave, during which the aortic wall recoils and is necessary. propels blood into the arterial network. The diastolic pres- • Understanding of the principles of aseptic technique is sure is measured as the lowest point of the diastolic needed. downslope, which should be less than 80 mm Hg in • Conditions that warrant the use of arterial pressure moni- adults. 21 toring include patients with the following: • The difference between the systolic and diastolic pres- ❖ Frequent blood sampling: sures is the pulse pressure, with a normal value of about Respiratory conditions requiring arterial blood gas 40 mm Hg. monitoring (oxygenation, ventilation, acid-base • Arterial pressure is determined by the relationship between status) blood fl ow through the vessels (cardiac output) and the Bleeding, actual or potential resistance of the vessel walls (systemic vascular resis- Electrolyte or glycemic abnormalities, actual or tance). -

Reducing Arterial Catheters

Reducing the Risk of Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections: Peripheral Arterial Catheters Amy Bardin Spencer, EdD(c), MS, RRT, VA-BC™ Manager, Clinical Marketing – Strategic Programs – Teleflex Russ Olmsted, MPH, CIC Director, Infection Prevention & Control, Trinity Health Paid consultant, Ethicon, BIOPATCH products Disclosure • This presentation reflects the technique, approaches and opinions of the individual presenters. This Ethicon sponsored presentation is not intended to be used as a training guide. The steps demonstrated may not be the complete steps of the procedure. Before using any medical device, review all relevant package inserts with particular attention to the indications, contraindications, warnings and precautions, and steps for use of the device(s). • Amy Bardin Spencer and Russ Olmsted are compensated by and presenting on behalf of Ethicon and must present information in accordance with applicable regulatory requirements. 0.8% of arterial lines become infected Maki DG et al., Mayo Clinic Proc 2006;81:1159-1171. Are You Placing Arterial Catheters? 16,438 per day 6,000,000 arterial catheters 680 every hour Maki DG et al., Mayo Clinic Proc 2006;81:1159-1171. 131 per day 48,000 arterial catheter-related bloodstream infections 5 patients every hour Maki DG et al., Mayo Clinic Proc 2006;81:1159-1171. Risk Factors • Lack of insertion compliance • No surveillance procedure • No bundle specific to arterial device insertion or maintenance • Multiple inserters with variations in skill set Maki DG et al., Mayo Clinic Proc 2006;81:1159-1171. -

Arterial Line

Arterial Line An arterial line is a thin catheter inserted into an artery. Arterial line placement is a common procedure in various critical care settings. It is most commonly used in intensive care medicine and anesthesia to monitor blood pressure directly and in real time (rather than by intermittent and indirect measurement, like a blood pressure cuff) and to obtain samples for arterial blood gas analysis. There are specific insertion sites, trained personnel and procedures for arterial lines. There are also specific techniques for drawing a blood sample from an A-Line or arterial line. An arterial line is usually inserted into the radial artery in the wrist, but can also be inserted into the brachial artery at the elbow, into the femoral artery in the groin, into the dorsalis pedis artery in the foot, or into the ulnar artery in the wrist. In both adults and children, the most common site of cannulation is the radial artery, primarily because of the superficial nature of the vessel and the ease with which the site can be maintained. Additional advantages of radial artery cannulation include the consistency of the anatomy and the low rate of complications. After the radial artery, the femoral artery is the second most common site for arterial cannulation. One advantage of femoral artery cannulation is that the vessel is larger than the radial artery and has stronger pulsation. Additional advantages include decreased risk of thrombosis and of accidental catheter removal, though the overall complication rate remains comparable. There has been considerable debate over whether radial or femoral arterial line placement more accurately measures blood pressure and mean arterial pressure, however, both approaches seem to perform well for this function. -

Development of a Large Animal Model of Lethal Polytrauma and Intra

Open access Original research Trauma Surg Acute Care Open: first published as 10.1136/tsaco-2020-000636 on 1 February 2021. Downloaded from Development of a large animal model of lethal polytrauma and intra- abdominal sepsis with bacteremia Rachel L O’Connell, Glenn K Wakam , Ali Siddiqui, Aaron M Williams, Nathan Graham, Michael T Kemp, Kiril Chtraklin, Umar F Bhatti, Alizeh Shamshad, Yongqing Li, Hasan B Alam, Ben E Biesterveld ► Additional material is ABSTRACT abdomen and pelvic contents. The same review published online only. To view, Background Trauma and sepsis are individually two of showed that of patients with whole body injuries, please visit the journal online 1 (http:// dx. doi. org/ 10. 1136/ the leading causes of death worldwide. When combined, 37.9% had penetrating injuries. The abdomen is tsaco- 2020- 000636). the mortality is greater than 50%. Thus, it is imperative one area of the body which is particularly suscep- to have a reproducible and reliable animal model to tible to penetrating injuries.2 In a review of patients Surgery, Michigan Medicine, study the effects of polytrauma and sepsis and test novel in Afghanistan with penetrating abdominal wounds, University of Michigan, Ann treatment options. Porcine models are more translatable the majority of injuries were to the gastrointes- Arbor, Michigan, USA to humans than rodent models due to the similarities tinal tract with the most common injury being to 3 Correspondence to in anatomy and physiological response. We embarked the small bowel. While this severe constellation Dr Glenn K Wakam; gw akam@ on a study to develop a reproducible model of lethal of injuries is uncommon in the civilian setting, med. -

Hemodynamic Profiles Related to Circulatory Shock in Cardiac Care Units

REVIEW ARTICLE Hemodynamic profiles related to circulatory shock in cardiac care units Perfiles hemodinámicos relacionados con el choque circulatorio en unidades de cuidados cardiacos Jesus A. Gonzalez-Hermosillo1, Ricardo Palma-Carbajal1*, Gustavo Rojas-Velasco2, Ricardo Cabrera-Jardines3, Luis M. Gonzalez-Galvan4, Daniel Manzur-Sandoval2, Gian M. Jiménez-Rodriguez5, and Willian A. Ortiz-Solis1 1Department of Cardiology; 2Intensive Cardiovascular Care Unit, Instituto Nacional de Cardiología Ignacio Chávez; 3Inernal Medicine, Hospital Ángeles del Pedregal; 4Posgraduate School of Naval Healthcare, Universidad Naval; 5Interventional Cardiology, Instituto Nacional de Cardiología Ignacio Chávez. Mexico City, Mexico Abstract One-third of the population in intensive care units is in a state of circulatory shock, whose rapid recognition and mechanism differentiation are of great importance. The clinical context and physical examination are of great value, but in complex situa- tions as in cardiac care units, it is mandatory the use of advanced hemodynamic monitorization devices, both to determine the main mechanism of shock, as to decide management and guide response to treatment, these devices include pulmonary flotation catheter as the gold standard, as well as more recent techniques including echocardiography and pulmonary ultra- sound, among others. This article emphasizes the different shock mechanisms observed in the cardiac care units, with a proposal for approach and treatment. Key words: Circulatory shock. Hemodynamic monitorization. -

Placement of an Arterial Line

T h e ne w engl a nd jour na l o f medicine videos in clinical medicine Placement of an Arterial Line Ken Tegtmeyer, M.D., Glenn Brady, M.D., Susanna Lai, M.P.H., Richard Hodo, and Dana Braner, M.D. Indications Radial arterial lines are important tools in the treatment of critically ill patients. From the Departments of Medical Infor- Continuous monitoring of blood pressure is indicated for patients with hemody- matics and Clinical Epidemiology and Pediatrics, Oregon Health and Sciences namic instability that requires inotropic or vasopressor medication. An arterial line University, Portland, Oreg. Address re- allows for consistent and continuous monitoring of blood pressure to facilitate the print requests to Dr. Braner at 3181 S.W. reliable titration of supportive medications. In addition, arterial lines allow for reli- Sam Jackson Park Rd., Portland, OR 97239-3098, or at [email protected]. able access to the arterial circulation for the measurement of arterial oxygenation and for frequent blood sampling. The placement of arterial lines is an important N Engl J Med 2006;354:e13. skill for physicians to master as they treat critically ill patients. Copyright © 2006 Massachusetts Medical Society. An arterial line is also indicated for patients with significant ventilatory deficits. Measurement of the partial pressures of arterial oxygen and arterial carbon dioxide provides more information about the status of gas exchange than does arterial oxygen saturation. Contraindications The contraindications to the placement of an arterial line are few but specific. Placement of an arterial line should not compromise the circulation distal to the placement site, which means that sites with known deficiencies in collateral circu- lation — such as those involved in Raynaud’s phenomenon and thromboangiitis obliterans or end arteries such as the brachial artery — should be avoided. -

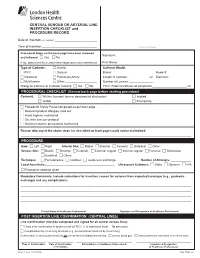

CENTRAL VENOUS OR ARTERIAL LINE INSERTION CHECKLIST and PROCEDURE RECORD

CENTRAL VENOUS OR ARTERIAL LINE INSERTION CHECKLIST and PROCEDURE RECORD Date of Insertion (YYYY/MM/DD): _________________________________ Time of Insertion:___________________________________________ ADDRESSOGRAPH Procedural Steps on the back page have been reviewed Signature:____________________________________________________________ and followed: c Yes c No If no, document the reason why steps were not maintained. Print Name: __________________________________________________________ Type of Catheter: c Arterial Catheter Model: c PICC c Dialysis Brand: ________________________________ Model #: __________________ c Introducer c Pulmonary Artery Length of catheter: ________________ cm Diameter: _________________ c Multi-lumen c Other:_________________________ Number of Lumens:___________________ Allergy to Catheter or Catheter Coating c Yes c No PICC: External catheter at completion___________________________ cm PROCEDURAL CHECKLIST (Review back page before starting procedure) Consent: c Written (consent form or documented discussion) c Implied c Verbal c Emergency c Procedural Safety Pause completed as per back page c Relevant product allergies ruled out c Hand hygiene maintained c Site/skin care per protocol c Maximum barrier precautions maintained Reason why any of the above steps (as described on back page) could not be maintained: ___________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PROCEDURE Side: c Left c Right -

Shock and Circulatory Support

17 Emerg Med J: first published as 10.1136/emj.2003.012450 on 20 December 2004. Downloaded from REVIEW Critical care in the emergency department: shock and circulatory support C A Graham, T R J Parke ............................................................................................................................... Emerg Med J 2005;22:17–21. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.012450 Effective resuscitation includes the rapid identification and will produce organ failure and, in the context of global hypoperfusion, multiple organ failure correction of an inadequate circulation. Shock is said to be ensues. The aim of resuscitation is to prevent present when systemic hypoperfusion results in severe shock worsening and to restore the circulation to dysfunction of the vital organs. The finding of normal a level that meets the body’s tissue oxygen requirements. haemodynamic parameters, for example blood pressure, Shock can arise through a variety of mechan- does not exclude shock in itself. This paper reviews the isms. Pump failure may be attributable to pathophysiology, resuscitation, and continuing inadequate preload (for example, severe bleed- ing), myocardial failure, or excessive afterload. management of the patient presenting with shock to the Shock can also occur with an adequate or emergency department. increased cardiac output as seen in distributive ........................................................................... shock (for example, septic or anaphylactic shock). Vital tissues remain ischaemic as much of the cardiac output -

Critical Review Form Therapy Early Goal Directed Therapy in Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock, NEJM 2001; 345: 1368-1377

Critical Review Form Therapy Early Goal Directed Therapy in Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock, NEJM 2001; 345: 1368-1377 Objective: To examine “whether early goal-directed therapy before admission to the ICU effectively reduces the incidence of multi-organ dysfunction, mortality, and the use of health care resources among patients with severe sepsis or septic shock.” (p. 1369) Methods: Open, randomized, partially blinded trial” (p. 1376). See CONSORT diagram (Figure 1, p. 1369) for an overview of patient enrollment and hemodynamic support. Eligible if > 18 years old presenting between March 1997 and March 2000 to Henry Ford Hospital (Detroit, MI) without bleeding risk, complicated sepsis (such as concurrent acute coronary syndrome or cardiogenic shock), atypical immune system (HIV or cancer), or contra-indications to invasive procedures. Eligible subjects also had to possess a systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg (after a 20-30 cc/kg bolus over 30-minutes) OR lactate > 4mmol/L AND two out of five of the following: 36°C > T > 38°C, heart rate > 90, respiratory rate > 20, partial pressure of carbon dioxide < 32 mm Hg, 4 > WBC > 12 OR >10% Bands. “The study was conducted during the routine treatment of other patients in the ED” (p. 1370) in a setting nearly identical to TCC at BJH. Patients were followed up to 60-days or death. Primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes included resuscitation endpoints, organ dysfunction, severity scores (APACHE II, SAPS II, MODS – see the original article for references if you are not familiar with these scoring systems), coagulation related variables, administered treatments, and the consumption of healthcare resources. -

Peripheral Arterial Catheters As a Source of Sepsis in the Critically Ill: a Narrative Review

Assessment of peripheral arterial catheters as a source of sepsis in the critically ill: a narrative review Author Gowardman, JR, Lipman, J, Rickard, CM Published 2010 Journal Title Journal of Hospital Infection DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2010.01.005 Copyright Statement © 2010 The Healthcare Infection Society. This is the author-manuscript version of this paper. Reproduced in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/35477 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au 1 Title: Peripheral arterial catheters (AC) as a source of sepsis in the critically ill -overrated or underemphasised- a narrative review. Running Title – Arterial lines and sepsis – a review John R Gowardman Senior Specialist, Royal Brisbane and Woman’s Hospital, Herston, Brisbane, AUSTRALIA , Senior Lecturer, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD,AUSTRALIA Associate Professor, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Brisbane, QLD, AUSTRALIA Jeffrey Lipman, Professor and Head, Anesthesiology and Critical Care University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, AUSTRALIA. Claire M Rickard Professor of Nursing, Griffith University Research Centre for Clinical Practice Innovation, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Brisbane, QLD, AUSTRALIA Address for correspondence: Dr John Gowardman, Senior Specialist, Department of Intensive Care Medicine Level 3, Ned Hanlon Building Royal Brisbane and Woman’s Hospital, Herston, Brisbane, QLD 4029 E mail: [email protected] 2 Summary Intravascular devices (IVD) are essential in the management of critically ill patients however IVD related sepsis continues to remain a major complication. Arterial lines (AC) are one of the most manipulated IVD in critically ill patients. -

Intra-Aortic Balloon Counterpulsation Learning Package (Liverpool)

2016 INTRA AORTIC BALLOON COUNTERPULSATION LEARNING PACKAGE Paula Nekic, CNE Liverpool ICU SWSLHD 2/26/2016 Liverpool Hospital Intensive Care: Learning Packages Intensive Care Unit Intra-Aortic Balloon Counterpulsation Learning Package Contents 1. Anatomy & Physiology 3 2. How does IABP work? 13 3. Indications 15 4. Contraindications 15 5. IABP- Components 16 6. Insertion of IABP 18 7. Set up of the IABP Console 20 8. Timing 20 9. Trigger 22 10. IABP Waveforms 23 11. Management 28 12. Troubleshooting 30 13. Weaning 33 14. Removal 33 15. Reference List 35 LH_ICU2016_Learning_Package_Intra_Aortic_Balloon_Pump_Learning_Package 2 | P a g e Liverpool Hospital Intensive Care: Learning Packages Intensive Care Unit Intra-Aortic Balloon Counterpulsation Learning Package ANATOMY & PHYSIOLOGY . Heart is the centre of the cardiovascular system. It is a muscular organ located between the lungs in the mediastinum. The adult heart is about the size of a closed fist. The blood vessels form a network of tubes that carry the blood from the heart to the tissues of the body and then return it to the heart LH_ICU2016_Learning_Package_Intra_Aortic_Balloon_Pump_Learning_Package 3 | P a g e Liverpool Hospital Intensive Care: Learning Packages Intensive Care Unit Intra-Aortic Balloon Counterpulsation Learning Package Chambers of the Heart The heart has four chambers Right and Left Atrium Are the smaller upper chambers of the heart The left atrium receives blood from the lungs The right atrium receives blood from the rest of the body The atrium allows approx 75% of blood flow directly from atria into ventricles prior to atria contracting. Atrial contraction adds 25% of filling to the ventricles; this is referred to as atrial kick. -

Arterial Line - Adult

Policies & Procedures Title: HEMODYNAMIC MONITORING - ARTERIAL LINE - ADULT . Assisting with insertion . Invasive site care . Blood sampling . Removal I.D. Number: 1092 Authorization: Source: Critical Care Committee Cross Index: [x] SHR Nursing Practice Committee Date Revised: September 2013 [ ] Tri-Site Critical Care Committee Date Effective: December 1999 Scope: Saskatoon City Hospital Royal University Hospital St. Paul’s Hospital Any PRINTED version of this document is only accurate up to the date of printing 26-Nov-13. Saskatoon Health Region (SHR) cannot guarantee the currency or accuracy of any printed policy. Always refer to the Policies and Procedures site for the most current versions of documents in effect. SHR accepts no responsibility for use of this material by any person or organization not associated with SHR. No part of this document may be reproduced in any form for publication without permission of SHR. 1. PURPOSE 1.1 To maintain the patency of arterial lines 1.2 To minimize the risk of infection, damage, displacement and other complications associated with the care and use of hemodynamic lines. 1.3 To provide accurate invasive pressure monitoring. 1.4 To facilitate blood withdrawal for diagnostic and patient management purposes. 2. POLICY Staff who will perform Registered Nurses as identified by their manager, will be certified in these procedures this Special Nursing Procedure/Added Skill to care for arterial lines in accordance with the SHR policy. Registered Respiratory Therapists Physician order Required for insertion and discontinuation of arterial monitoring Special Considerations Prior to accessing arterial lines, clinician must perform appropriate Hand Hygiene procedures For radial arterial line, a Modified Allen’s Test is responsibility of person inserting catheter.