The Language of the Unheard: Social Media and Riot Subculture/S Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Additional Document

-“Both Spectacular and Unremarkable” Letter of Allegation regarding the Excessive Use of Force and Discrimination by the Philadelphia Police Department in response to Black Lives Matter protests in May and June of 2020 Prepared and submitted by the Andy and Gwen Stern Community Lawyering Clinic of the Drexel University Thomas R. Kline School of Law and the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania as a Joint Submission to the UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions. Much of the credit for this submission belongs to the volunteers who spent countless hours investigating and documenting the events recounted here, as well as interviewing witnesses and victims, editing, and repeatedly verifying the accuracy of this submission. We thank Cal Barnett-Mayotte, Jeremy Gradwohl, Connor Hayes, Tue Ho, Bren Jeffries, Ryan Nasino, Juan Palacio Moreno, Lena Popkin, Katie Princivalle, Caitlin Rooney, Abbie Starker, Ceara Thacker, and William Walker. Cc: Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance Special Rapporteur on Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The tragic killings of George Floyd in Minneapolis and Breonna Taylor in Louisville, and the ongoing and disproportionate killings of Black and Brown people by law enforcement throughout the United States, have sparked demonstrations against police brutality and racism in all fifty states – and around the world. Given Philadelphia’s own history of racially discriminatory policing, it was expected and appropriate that such protests would happen here as well. -

Case 2:21-Cv-00852 Document 1 Filed 04/28/21 Page 1 of 75

Case 2:21-cv-00852 Document 1 Filed 04/28/21 Page 1 of 75 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA REMINGTYN A. WILLIAMS, LAUREN E. Civil Action No. CHUSTZ, and BILAL ALI-BEY, on behalf of themselves and all other persons similarly Judge situated, Section Plaintiffs v. Magistrate SHAUN FERGUSON IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS SUPERINTENDENT OF THE JURY TRIAL DEMANDED NEW ORLEANS POLICE DEPARTMENT; LAMAR A. DAVIS IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS SUPERINTENDENT OF THE LOUISIANA STATE POLICE; JOSEPH P. LOPINTO IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS SHERIFF OF JEFFERSON PARISH; OFFICER TRAVIS JOHNSON; OFFICER JASON JORGENSON; OFFICER DEVIN JOSEPH; OFFICER MICHAEL PIERCE; SERGEANT TRAVIS WARD; OFFICER DAVID DESALVO; OFFICER WESLEY HUMBLES; OFFICER ARDEN TAYLOR, JR.; OFFICER FRANK VITRANO; SERGEANT EVAN COX; LIEUTENANT MERLIN BUSH; OFFICER MICHAEL DEVEZIN; OFFICER BRYAN BISSELL; OFFICER DANIEL GRIJALVA; OFFICER BRANDON ABADIE; OFFICER DEVIN JOHNSON; OFFICER DOUGLAS BOUDREAU; OFFICER MATTHEW CONNOLLY; SERGEANT TERRENCE HILLIARD; OFFICER JONATHAN BURNETTE; OFFICER JUSTIN MCCUBBINS; OFFICER KENNETH KUYKINDALL; OFFICER ZACHARY VOGEL; SERGEANT LAMONT WALKER; OFFICER DENZEL MILLON; OFFICER RAPHAEL RICO; 1 Case 2:21-cv-00852 Document 1 Filed 04/28/21 Page 2 of 75 OFFICER JAMAL KENDRICK; SERGEANT DANIEL HIATT; OFFICER JEFFREY CROUCH; OFFICER JOHN CABRAL; OFFICER MATTHEW EZELL; OFFICER JAMES CUNNINGHAM; OFFICER DEMOND DAVIS; OFFICER JOSHUA DIAZ; SERGEANT STEPHEN NGUYEN; OFFICER VINH NGUYEN; OFFICER MATTHEW MCKOAN; CAPTAIN BRIAN LAMPARD; CAPTAIN LEJON ROBERTS; DEPUTY CHIEF JOHN THOMAS; JOHN DOES 1-100; JOHN POES 1-50; JOHN ROES 1-50, Defendants 2 Case 2:21-cv-00852 Document 1 Filed 04/28/21 Page 3 of 75 CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT INTRODUCTION 1. -

Technological Surveillance and the Spatial Struggle of Black Lives Matter Protests

No Privacy, No Peace? Technological Surveillance and the Spatial Struggle of Black Lives Matter Protests Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with research distinction in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Eyako Heh The Ohio State University April 2021 Project Advisor: Professor Joel Wainwright, Department of Geography I Abstract This paper investigates the relationship between technological surveillance and the production of space. In particular, I focus on the surveillance tools and techniques deployed at Black Lives Matter protests and argue that their implementation engenders uneven outcomes concerning mobility, space, and power. To illustrate, I investigate three specific forms and formats of technological surveillance: cell-site simulators, aerial surveillance technology, and social media monitoring tools. These tools and techniques allow police forces to transcend the spatial-temporal bounds of protests, facilitating the arrests and subsequent punishment of targeted dissidents before, during, and after physical demonstrations. Moreover, I argue that their unequal use exacerbates the social precarity experienced by the participants of demonstrations as well as the racial criminalization inherent in the policing of majority Black and Brown gatherings. Through these technological mediums, law enforcement agents are able to shape the physical and ideological dimensions of Black Lives Matter protests. I rely on interdisciplinary scholarly inquiry and the on- the-ground experiences of Black Lives Matter protestors in order to support these claims. In aggregate, I refer to this geographic phenomenon as the spatial struggle of protests. II Acknowledgements I extend my sincerest gratitude to my advisor and former professor, Joel Wainwright. Without your guidance and critical feedback, this thesis would not have been possible. -

Social Media Overview

Social Media Overview Presented by Rita Gavelis Technology Trainer / Consultant Facebook • Founded in 2004 • 840+ Million active users • 483 million daily active users logged onto Facebook in December 2011 • People spend over 700 billion minutes per month on Facebook Facebook Personal Accounts Allow you to share thoughts, photos, videos, games, and more with family and friends. Anyone over the age of 13 can create a Facebook account. Personal accounts are meant for individual people, not their pets, businesses, or interests. Facebook Groups Facebook groups are meant for small groups of people who share the same interests. It might be a discussion group focused on knitting, reading, motorcycles, movies, and, well, just about everything. Anyone can create a group. Facebook Pages Pages are meant for businesses, Buildings, Locations, Entertainers, and Artists. Only representatives of the above are allowed to create a page. Creating a Facebook page gives you a bigger web presence. Facebook pages show up in Google searches. Business Pages • Victory Motorcycles • AccountingCoach.com • American Airlines • Zappos • Beverly Hospital These are just a few examples Twitter • Twitter is a micro-blogging service • Founded in 2006 • Over 100 million active users • Over 230 million tweets per day 2 Key Events for Twitter Dec 21, 2008 – Continental Airlines jet veers off runway in Denver. News of the accident was first broadcast by a passenger via twitter. http://twitter.com/#!/2drinksbehind/status/1069832870 Jan 15, 2009 – US Airways flight 1549 made a miracle landing on the Hudson. A commuter on a nearby ferry broadcast the very first image of the plane in the water via Twitpic. -

Cycle of Misconduct:How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed to Police Its Police

DePaul Journal for Social Justice Volume 10 Issue 1 Winter 2017 Article 2 February 2017 Cycle of Misconduct:How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed To Police Its Police Elizabeth J. Andonova Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jsj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legislation Commons, Public Law and Legal Theory Commons, and the Social Welfare Law Commons Recommended Citation Elizabeth J. Andonova, Cycle of Misconduct:How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed To Police Its Police, 10 DePaul J. for Soc. Just. (2017) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jsj/vol10/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal for Social Justice by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Andonova: Cycle of Misconduct:How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed To Police I Author: Elizabeth J. Andonova Source: The National Lawyers Guild Source Citation: 73 LAW. GUILD REV. 2 (2016) Title: Cycle of Misconduct: How Chicago Has Repeatedly Failed to Police the Police Republication Notice This article is being republished with the express consent of The National Lawyers Guild. This article was originally published in the National Lawyers Guild Summer 2016 Review, Volume 73, Number 2. That document can be found at: https://www.nlg.org/nlg-review/wp- content/uploads/sites/2/2016/11/NLGRev-73-2-final-digital.pdf. The DePaul Journal for Social Justice would like to thank the NLG for granting us the permission to republish this article. -

A Little Birdie Told Me About Agriculture: Best Practices and Future Uses of Twitter in Agriculutral Communications

Journal of Applied Communications Volume 94 Issue 3 Nos. 3 & 4 Article 2 A Little Birdie Told Me About Agriculture: Best Practices and Future Uses of Twitter in Agriculutral Communications Katie Allen Katie Abrams Courtney Meyers See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/jac This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License. Recommended Citation Allen, Katie; Abrams, Katie; Meyers, Courtney; and Shultz, Alyx (2010) "A Little Birdie Told Me About Agriculture: Best Practices and Future Uses of Twitter in Agriculutral Communications," Journal of Applied Communications: Vol. 94: Iss. 3. https://doi.org/10.4148/1051-0834.1189 This Professional Development is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Applied Communications by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Little Birdie Told Me About Agriculture: Best Practices and Future Uses of Twitter in Agriculutral Communications Abstract Social media sites, such as Twitter, are impacting the ways businesses, organizations, and individuals use technology to connect with their audiences. Twitter enables users to connect with others through 140-character messages called “tweets” that answer the question, “What’s happening?” Twitter use has increased exponentially to more than five million active users but has a dropout rate of more than 50%. Numerous agricultural organizations have embraced the use of Twitter to promote their products and agriculture as a whole and to interact with audiences in a new way. -

First Amended Complaint Alleges As Follows

Case 1:20-cv-10541-CM Document 48 Filed 03/05/21 Page 1 of 30 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK In Re: New York City Policing During Summer 2020 Demonstrations No. 20-CV-8924 (CM) (GWG) WOOD FIRST AMENDED This filing is related to: CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT AND Charles Henry Wood, on behalf of himself JURY DEMAND and all others similarly situated, v. City of New York et al., No. 20-CV-10541 Plaintiff Charles Henry Wood, on behalf of himself and all others similarly situated, for his First Amended Complaint alleges as follows: PRELIMINARY STATEMENT 1.! When peaceful protesters took to the streets of New York City after the murder of George Floyd in the summer of 2020, the NYPD sought to suppress the protests with an organized campaign of police brutality. 2.! A peaceful protest in Mott Haven on June 4, 2020 stands as one of the most egregious examples of the NYPD’s excessive response. 3.! It also illustrates the direct responsibility that the leaders of the City and the NYPD bear for the NYPD’s conduct. 4.! Before curfew went into effect for the evening, police in riot gear surrounded peaceful protesters and did not give them an opportunity to disperse. 5.! The police then charged the protesters without warning; attacked them indiscriminately with shoves, blows, and baton strikes; handcuffed them with extremely tight plastic zip ties; and detained them overnight in crowded and unsanitary conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. 1 Case 1:20-cv-10541-CM Document 48 Filed 03/05/21 Page 2 of 30 6.! The NYPD’s highest-ranking uniformed officer, Chief of Department Terence Monahan, was present at the protest and personally oversaw and directed the NYPD’s response. -

Declaration of Ryan Bricker in Support of 2 Ex Parte Motion for Temporary

Sony Computer Entertainment America LLC v. Hotz et al Doc. 42 Att. 17 EXHIBIT Q DECLARATION OF RYAN BRICKER IN SUPPORT OF EX PARTE MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE RE PRELIMINARY INUNCTION; ORDER OF IMPOUNDMENT Dockets.Justia.com bushing (gnihsub) on Twitter http://twitter.com/gnihsub Skip past navigation On a mobile phone? Check out m.twitter.com! Skip to navigation Skip to sign in form Have an account?Sign in Username or email Password Remember me Forgot password? Forgot username? Already using Twitter on your phone? Get updates via SMS by texting follow gnihsub to 40404 in the United States Two-way (sending and receiving) short codes: Country Code For customers of Australia 0198089488 Telstra Canada 21212 (any) United Kingdom 86444 Vodafone, Orange, 3, O2 Indonesia 89887 AXIS, 3, Telkomsel Ireland 51210 O2 1 of 9 1/9/2011 12:15 PM bushing (gnihsub) on Twitter http://twitter.com/gnihsub Two-way (sending and receiving) short codes: India 53000 Bharti Airtel, Videocon Jordan 90903 Zain New Zealand 8987 Vodafone, Telecom NZ United States 40404 (any) Codes for other countries Name bushing Location California Web http://hackmii.com Bio tinkerer 72 4,173 332 Following Followers Listed 1. fail0verflow Seems YouTube refuses to do anything about impersonation reports. Everyone please flag "fail0verflow"'s 117Tweets videos as Spam->Scams/Fraud. Friday, December 31, 2010 Favorites 9:22:25 PM via Choqok Retweeted by gnihsub and 31 others 2. rootlabs PS3 priv signing key exposed. Apparently Sony does not read our blog. http://is.gd/hrxqb Congrats: @gnihsub @marcan42 @fail0verflow #27c3 Wednesday, December 29, 2010 5:17:50 PM via web Retweeted by gnihsub and 100+ others @gnihsub/fail 3. -

The Complete Guide to Social Media from the Social Media Guys

The Complete Guide to Social Media From The Social Media Guys PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 08 Nov 2010 19:01:07 UTC Contents Articles Social media 1 Social web 6 Social media measurement 8 Social media marketing 9 Social media optimization 11 Social network service 12 Digg 24 Facebook 33 LinkedIn 48 MySpace 52 Newsvine 70 Reddit 74 StumbleUpon 80 Twitter 84 YouTube 98 XING 112 References Article Sources and Contributors 115 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 123 Article Licenses License 125 Social media 1 Social media Social media are media for social interaction, using highly accessible and scalable publishing techniques. Social media uses web-based technologies to turn communication into interactive dialogues. Andreas Kaplan and Michael Haenlein define social media as "a group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, which allows the creation and exchange of user-generated content."[1] Businesses also refer to social media as consumer-generated media (CGM). Social media utilization is believed to be a driving force in defining the current time period as the Attention Age. A common thread running through all definitions of social media is a blending of technology and social interaction for the co-creation of value. Distinction from industrial media People gain information, education, news, etc., by electronic media and print media. Social media are distinct from industrial or traditional media, such as newspapers, television, and film. They are relatively inexpensive and accessible to enable anyone (even private individuals) to publish or access information, compared to industrial media, which generally require significant resources to publish information. -

Final List George Floyd

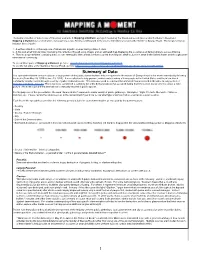

The below collection of data is one of three key elements in Mapping a Moment, a project created by the Cleveland based musical duo the Baker’s Basement. Mapping a Moment was crafted after a long journey across America and beyond in the weeks immediately following the murder of George Floyd. The full presentation includes these 3 parts: 1. A written reflection on the response of Americans in public spaces during a time of crisis 2. A five and a half minute video illustrating this reflection through song, image, and an animated map displaying the occurrence of demonstrations across America 3. The below spreadsheet containing data on over 1600 public demonstrations that occurred from May 25, 2020 to June 13, 2020 in the United States and throughout the international community. To see all three parts of Mapping a Moment, go here: www.thebakersbasement.com/mapping-a-moment To see the full video of the murder of George Floyd, go here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zaGmz4DPlJw&app=desktop&bpctr=1596415559 Summary of Data: The spreadsheet below contains data on a large portion of the public demonstrations held in response to the murder of George Floyd in the weeks immediately following his death (From May 25, 2020 to June 13, 2020). It was collected to help provide a wider understanding of how people in the United States and the international community initially reacted through a variety of public demonstrations. This data was used to construct the animated map presented in the video & song portion of Mapping a Moment - Youtube. This is not to be considered a complete list of the demonstrations that occurred during that time period, but an effort to create a fuller picture of how the USA and the international community reacted in public spaces. -

Rioting and Time

Rioting and time Collective violence in Manchester, Liverpool and Glasgow, 1800-1939 A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 Matteo Tiratelli School of Social Sciences 1 Table of contents Abstract 4 Declaration & Copyright 5 Acknowledgements 6 Chapter 1 — Rioting and time 7 Chapter 2 — Don’t call it a riot 24 Chapter 3 — Finding riots and describing them 42 Chapter 4 — Riots in space, time and society 64 Chapter 5 — The changing practice of rioting 102 Chapter 6 — The career of a riot: triggers and causes 132 Chapter 7 — How do riots sustain themselves? 155 Chapter 8 — Riots: the past and the future 177 Bibliography 187 Appendix 215 Word count: 70,193 2 List of tables Table 1: The spaces where riots started 69 Table 2: The places where riots started 70 Table 3: The number of riots happening during normal working hours 73 Table 4: The number of riots which happen during particular calendrical events 73 Table 5: The proportion of non-industrial riots by day of the week 75 Table 6: The likelihood of a given non-industrial riot being on a certain day of the week 75 Table 7: The likelihood of a given riot outside of Glasgow involving prison rescues 98 Table 8: The likelihood of a given riot involving begging or factory visits 111 Table 9: The likelihood of a given riot targeting specific individuals or people in their homes 119 List of figures Figure 1: Angelus Novus (1920) by Paul Klee 16 Figure 2: Geographic spread of rioting in Liverpool 67 Figure 3: Geographic spread of rioting in Manchester 68 Figure 4: Geographic spread of rioting in Glasgow 68 Figure 5: The number of riots per year 78 Figure 6: The number of riots involving prison rescues per year 98 3 Abstract The 19th century is seen by many as a crucial turning point in the history of protest in Britain and across the global north.