The Relationship of Self-Concept to Adolescent's Musical Preferences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ed Phelps Logs His 1,000 DTV Station Using Just Himself and His DTV Box. No Autologger Needed

The Magazine for TV and FM DXers October 2020 The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association Being in the right place at just the right time… WKMJ RF 34 Ed Phelps logs his 1,000th DTV Station using just himself and his DTV Box. No autologger needed. THE VHF-UHF DIGEST The Worldwide TV-FM DX Association Serving the TV, FM, 30-50mhz Utility and Weather Radio DXer since 1968 THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, SAUL CHERNOS, KEITH MCGINNIS, JAMES THOMAS AND MIKE BUGAJ Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org/info Webmaster: Tim McVey Forum Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Creative Director: Saul Chernos Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, John Zondlo and Mike Bugaj The WTFDA Board of Directors Doug Smith Saul Chernos James Thomas Keith McGinnis Mike Bugaj [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Renewals by mail: Send to WTFDA, P.O. Box 501, Somersville, CT 06072. Check or MO for $10 payable to WTFDA. Renewals by Paypal: Send your dues ($10USD) from the Paypal website to [email protected] or go to https://www.paypal.me/WTFDA and type 10.00 or 20.00 for two years in the box. Our WTFDA.org website webmaster is Tim McVey, [email protected]. -

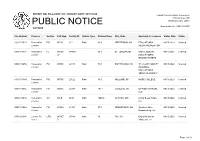

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission News Media Information 202-418-0500 445 12Th St., S.W

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission News Media Information 202-418-0500 445 12th St., S.W. Internet: http://www.fcc.gov Washington, D.C. 20554 TTY: 1-888-835-5322 Report No. 646 Media Bureau Call Sign Actions 01/11/2021 During the period from 12/01/2020 to 12/31/2020 the Commission accepted applications to assign call signs to, or change the call signs of the following broadcast stations. Call Signs Reserved for Pending Sales Applicants Call Sign Service Requested By City State File-Number Former Call Sign KNBI AM HANFORD YOUTH SERVICES INC MONTEREY CA BAL-20201006AAW KNRY New or Modified Call Signs Row Effective Former Call Call Sign Service Assigned To City State File Number Number Date Sign MOUNT WILSON FM BROADCASTERS, BEVERLY 1 12/01/2020 KMZT AM CA KSUR INC. HILLS STATE 2 12/01/2020 WLXD FM EDUCATIONAL MEDIA FOUNDATION MS WQJB COLLEGE 3 12/02/2020 WGKB AM NEW WRRD, LLC WAUKESHA WI WRRD 4 12/05/2020 KRXD FM NEW STAR BROADCASTING LLC MCNARY AZ KXMQ 5 12/07/2020 KFBU-LD LD WESTERN FAMILY TELEVISION, INC. BOZEMAN MT KJCQ-LD 6 12/08/2020 WDLR AM DELMAR COMMUNICATIONS, INC. MARYSVILLE OH WQTT 7 12/08/2020 WQCD AM DELMAR COMMUNICATIONS, INC. DELAWARE OH WDLR 8 12/08/2020 WWCD AM ICS COMMUNICATIONS, INC. COLUMBUS OH WMYC KKHQ- TOWNSQUARE MEDIA WATERLOO 9 12/09/2020 FM CEDAR FALLS IA KOEL-FM FM LICENSE, LLC TOWNSQUARE MEDIA WATERLOO 10 12/09/2020 KOEL-FM FM OELWEIN IA KKHQ-FM LICENSE, LLC 11 12/09/2020 WKIT FM THE ZONE CORPORATION BREWER ME WKIT-FM BALED- 12 12/11/2020 WGNW FM THE FAMILY RADIO NETWORK, INC. -

List of Radio Stations in Ohio

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia List of radio stations in Ohio From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page The following is a list of FCC-licensed radio stations in the U.S. state of Ohio, which can be sorted Contents by their call signs, frequencies, cities of license, licensees, and programming formats. Featured content Current events Call City of Frequency Licensee Format[3] Random article sign license[1][2] Donate to Wikipedia Radio Advantage One, Wikipedia store WABQ 1460 AM Painesville Gospel music LLC. Interaction Jewell Schaeffer WAGX 101.3 FM Manchester Classic hits Help Broadcasting Co. About Wikipedia Real Stepchild Radio of Community portal WAIF 88.3 FM Cincinnati Variety/Alternative/Eclectic Recent changes Cincinnati Contact page WAIS 770 AM Buchtel Nelsonville TV Cable, Inc. Talk Tools The Calvary Connection WAJB- What links here 92.5 FM Wellston Independent Holiness Southern Gospel LP Related changes Church Upload file WAKR 1590 AM Akron Rubber City Radio Group News/Talk/Sports Special pages open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Permanent link WAKS 96.5 FM Akron Capstar TX LLC Top 40 Page information WAKT- Toledo Integrated Media Wikidata item 106.1 FM Toledo LP Education, Inc. Cite this page WAKW 93.3 FM Cincinnati Pillar of Fire Church Contemporary Christian Print/export Dreamcatcher Create a book WAOL 99.5 FM Ripley Variety hits Communications, Inc. Download as PDF Printable version God's Final Call & Religious (Radio 74 WAOM 90.5 FM Mowrystown Warning, Inc. -

Inside This Issue

News Serving DX’ers since 1933 Volume 82, No. 7●December 29, 2014● (ISSN 0737-1639) Inside this issue . 2 … AM Switch 11 … Domestic DX Digest East 16 … College Sports Networks 5 … Membership Report 14 … International DX Digest 17 … Treasurer’s Report 6 … Domestic DX Digest West 15 … Musings of the Members 18 … Geo Indices/Space Wx Board Announcement: The NRC Board of DecaloMania in Fort Wayne, Indiana, July 10‐12, Directors is pleased to announce the 2015. More details will be forthcoming as our appointment of its newest member to the BoD to host Scott Fybush works them out. fill the vacant seat left by Ken Chatterton after DX Tests: If you want to help arrange tests, his resignation earlier this year. Dave Schmidt, contact Brandon Jordan, the NRC/IRCA Test who has served as Musings of the Members Coordination, at P.O. Box 338, Rossville TN editor for over twenty years and DDXD editor 38066, (901) 592‐9847, and [email protected]. before that, is our newest BoD member. Dave Brandon has set up a web site at also has a keen interest in record collecting and http://dxtests.net/ for the latest test info. And Internet radio (maybe he’ll tell you more in a follow him on Twitter @AMDXTests for the latest Musing soon!). Welcome, Dave! – Paul test info. Swearingen, NRC BoD Chairman. PARI DXpedition: Via the NASWA Journal, DXAS: Fred Vobbe has announced that he Thomas Witherspoon is planning a unique will be stepping down as publisher of the DX DXpedition to the Pisgah Astronomical Research Audio Service after the April 2015 issue. -

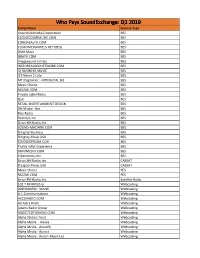

Who Pays SX Q3 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q3 2019 Entity Name License Type AMBIANCERADIO.COM BES Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES F45 Training Incorporated BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It's Never 2 Late BES Jukeboxy BES MANAGEDMEDIA.COM BES MIXHITS.COM BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES Music Maestro BES Music Performance Rights Agency, Inc. BES MUZAK.COM BES NEXTUNE.COM BES Play More Music International BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Startle International Inc. BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio #1 Gospel Hip Hop Webcasting 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 411OUT LLC Webcasting 630 Inc Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting AD VENTURE MARKETING DBA TOWN TALK RADIO Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting africana55radio.com Webcasting AGM Bakersfield Webcasting Agm California - San Luis Obispo Webcasting AGM Nevada, LLC Webcasting Agm Santa Maria, L.P. Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting -

Tattler 9/21

Volume XXXIII • Number 38 • September 21, 2007 checks and offer constructive advice on how to improve your on-air work. TalenTrak will be held November 10, 2007 at Columbia College in the heart of downtown Chicago. Tuition for AIN TREET the day is just $49 ($39 student/educator/free agent), and it M S includes lunch! To register, visit www.theconclave.com. Look Presents for the TalenTrak story, and click on the link featured to download TheThe ConclaveConclave a registration pdf document. The official TalenTrak hotel is the Travelodge Hotel, just one-half block from Columbia College. AA TT TT LL EE To secure a specially priced TalenTrak room at the Travelodge, TT RR contact TalenTrak room coordinator Darren Andrews at 312- 376-1481 or at his email address: Publisher: Tom Kay Editor: Kate Kennedy Cartoons Pilfered by Lenny Bronstein & Jay Philpott [email protected]. TalenTrak 2007 To “Len” An Ear; Former Conclave Keynoter and legendary radio programmer Kasper to Keynote! Chicago Cubs Steve Rivers comes back to the programming game, after being broadcaster Len Kasper has been named PD of CBS Radio Top 40/Mainstream KBKS/Seattle, tapped to keynote the 2007 edition of starting immediately. Rivers was most recently served as EVP the Conclave’s TalenTrak on Saturday, th and Pres./Programming for Pyramid Radio Inc., but has also November 10 at Columbia College/ been seen as SVP/Programming for CBS Radio, radio editor Chicago! Kasper, a Milwaukee native, and founding partner at Musicbiz, SVP/founding partner of is finishing his third season with the Radio Central, Chief Programming Officer at AM/FM, Cubs after doing Florida Marlins play- Chancellor Media, Evergreen Media, and Pyramid by-play for three years for Fox Sports Broadcasting. -

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media -

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-2-200917-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 09/17/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000113523 Renewal of FM WCVJ 612 Main 90.9 JEFFERSON, OH EDUCATIONAL 09/15/2020 Granted License MEDIA FOUNDATION 0000114058 Renewal of FL WSJB- 194835 96.9 ST. JOSEPH, MI SAINT JOSEPH 09/15/2020 Granted License LP EDUCATIONAL BROADCASTERS 0000116255 Renewal of FM WRSX 62110 Main 91.3 PORT HURON, MI ST. CLAIR COUNTY 09/15/2020 Granted License REGIONAL EDUCATIONAL SERVICE AGENCY 0000113384 Renewal of FM WTHS 27622 Main 89.9 HOLLAND, MI HOPE COLLEGE 09/15/2020 Granted License 0000113465 Renewal of FM WCKC 22183 Main 107.1 CADILLAC, MI UP NORTH RADIO, 09/15/2020 Granted License LLC 0000115639 Renewal of AM WILB 2649 Main 1060.0 CANTON, OH Living Bread Radio, 09/15/2020 Granted License Inc. 0000113544 Renewal of FM WVNU 61331 Main 97.5 GREENFIELD, OH Southern Ohio 09/15/2020 Granted License Broadcasting, Inc. 0000121598 License To LPD W30ET- 67049 Main 30 Flint, MI Digital Networks- 09/15/2020 Granted Cover D Midwest, LLC Page 1 of 62 REPORT NO. PN-2-200917-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 09/17/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

Exhibit 2181

Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 4 Electronically Filed Docket: 19-CRB-0005-WR (2021-2025) Filing Date: 08/24/2020 10:54:36 AM EDT NAB Trial Ex. 2181.1 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 2 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.2 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 3 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.3 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 4 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.4 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 132 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 1 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.5 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 133 Filed 04/15/20 Page 1 of 4 ATARA MILLER Partner 55 Hudson Yards | New York, NY 10001-2163 T: 212.530.5421 [email protected] | milbank.com April 15, 2020 VIA ECF Honorable Louis L. Stanton Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse 500 Pearl St. New York, NY 10007-1312 Re: Radio Music License Comm., Inc. v. Broad. Music, Inc., 18 Civ. 4420 (LLS) Dear Judge Stanton: We write on behalf of Respondent Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) to update the Court on the status of BMI’s efforts to implement its agreement with the Radio Music License Committee, Inc. (“RMLC”) and to request that the Court unseal the Exhibits attached to the Order (see Dkt. -

State of Ohio Emergency Alert System Plan

STATE OF OHIO EMERGENCY ALERT SYSTEM PLAN SEPTEMBER 2003 ASHTABULA CENTRAL AND LAKE LUCAS FULTON WILLIAMS OTTAWA EAST LAKESHORE GEAUGA NORTHWEST CUYAHOGA SANDUSKY DEFIANCE ERIE TRUMBULL HENRY WOOD LORAIN PORTAGE YOUNGSTOWN SUMMIT HURON MEDINA PAULDING SENECA PUTNAM MAHONING HANCOCK LIMA CRAWFORD ASHLAND VAN WERT WYANDOT WAYNE STARK COLUMBIANA NORTH RICHLAND ALLEN EAST CENTRAL ‘ HARDIN CENTRAL CARROLL HOLMES MERCER MARION AUGLAIZE MORROW JEFFERSON TUSCARAWAS KNOX LOGAN COSHOCTON SHELBY UNION HARRISON DELAWARE DARKE CHAMPAIGN LICKING GUERNSEY BELMONT MIAMI MUSKINGUM WEST CENTRAL FRANKLIN CLARK CENTRAL MONTGOMERY UPPER OHIO VALLEY MADISON PERRY NOBLE MONROE PREBLE FAIRFIELD GREENE PICKAWAY MORGAN FAYETTE HOCKING WASHINGTON BUTLER WARREN CLINTON ATHENS SOUTHWEST ROSS VINTON HAMILTON HIGHLAND SOUTHEAST MEIGS CLERMONT SOUTH CENTRAL PIKE JACKSON GALLIA BROWN ADAMS SCIOTO LAWRENCE Ohio Emergency Management Agency (EMA) (20) All Ohio County EMA Directors NWS Wilmington, OH NWS Cleveland, OH NWS Pittsburgh, PA NWS Charleston, WV NWS Fort Wayne, IN NWS Grand Rapids, MI All Ohio Radio and TV Stations All Ohio Cable Systems WOVK Radio, West Virginia Ohio Association of Broadcasters (OAB) Ohio SECC Chairman All Operational Area LECC Chairmen All Operational Area LECC Vice Chairmen Ohio SECC Cable Co-Chairman All Ohio County Sheriffs President, All County Commissioners Ohio Educational Telecommunications Network Commission (OET) Ohio Cable Telecommunications Association (OCTA) Michigan Emergency Management Agency Michigan SECC Chairman Indiana Emergency Management Agency Indiana SECC Chairman Kentucky Emergency Management Agency Kentucky SECC Chairman Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency Pennsylvania SECC Chairman West Virginia Emergency Management Agency West Virginia SECC Chairman Additional copies are available from: Ohio Emergency Management Agency 2855 West Dublin Granville Road Columbus, Ohio 43235-2206 (614) 889-7150 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. -

Hadiotv EXPERIMENTER AUGUST -SEPTEMBER 75C

DXer's DREAM THAT ALMOST WAS SHASILAND HadioTV EXPERIMENTER AUGUST -SEPTEMBER 75c BUILD COLD QuA BREE ... a 2-FET metal moocher to end the gold drain and De Gaulle! PIUS Socket -2 -Me CB Skyhook No -Parts Slave Flash Patrol PA System IC Big Voice www.americanradiohistory.com EICO Makes It Possible Uncompromising engineering-for value does it! You save up to 50% with Eico Kits and Wired Equipment. (%1 eft ale( 7.111 e, si. a er. ortinastereo Engineering excellence, 100% capability, striking esthetics, the industry's only TOTAL PERFORMANCE STEREO at lowest cost. A Silicon Solid -State 70 -Watt Stereo Amplifier for $99.95 kit, $139.95 wired, including cabinet. Cortina 3070. A Solid -State FM Stereo Tuner for $99.95 kit. $139.95 wired, including cabinet. Cortina 3200. A 70 -Watt Solid -State FM Stereo Receiver for $169.95 kit, $259.95 wired, including cabinet. Cortina 3570. The newest excitement in kits. 100% solid-state and professional. Fun to build and use. Expandable, interconnectable. Great as "jiffy" projects and as introductions to electronics. No technical experience needed. Finest parts, pre -drilled etched printed circuit boards, step-by-step instructions. EICOGRAFT.4- Electronic Siren $4.95, Burglar Alarm $6.95, Fire Alarm $6.95, Intercom $3.95, Audio Power Amplifier $4.95, Metronome $3.95, Tremolo $8.95, Light Flasher $3.95, Electronic "Mystifier" $4.95, Photo Cell Nite Lite $4.95, Power Supply $7.95, Code Oscillator $2.50, «6 FM Wireless Mike $9.95, AM Wireless Mike $9.95, Electronic VOX $7.95, FM Radio $9.95, - AM Radio $7.95, Electronic Bongos $7.95.