Property's Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A High School Tradition for 84 Years Volume 84, Number 6 Salem Senior High School March 14,1997

A High School Tradition for 84 Years Volume 84, Number 6 Salem Senior High School March 14,1997 In this issue Erica Godfrey, Connie Morris, and Stephanie Schmid look at the dangers ofsmoking. Smoke and choke Pay for your crime by Stephanie Schmid Smoking at Salem McShane, have asked juve hard-core smokers has also High School is a continu nile court judge Ashley decreased in contrast to the ing problem. The Pike to support them in al increasing number of stu restrooms have become a lowing them to cite smok dents sharing cigarettes. haven for smokers; the ers to court. This would The first time a most popular being in Se then become a legal matter student is caught smoking nior Hall. Even though vari in which smokers would be or possessing a tobacco ous staff members monitor punished with fines for un product, the punishment is the restrooms between derage possession of a to three days of in- school classes, it is still possible bacco product and smoking suspension. The second for students to ·smoke dur in a public building. time is five days and the ing classes. The rate of SHS third time is ten days of in Some public smokers fluctuates. The school suspension. If two buildings are fining smok overall number of smokers or more students are ers $50 if they are caught has decreased in the men's caught in the same stall, all smoking in places such as restrooms whereas in the are punished with four the restrooms. The princi women's restrooms it is on night detention. -

The Navigability Concept in the Civil and Common Law: Historical Development, Current Importance, and Some Doctrines That Don't Hold Water

Florida State University Law Review Volume 3 Issue 4 Article 1 Fall 1975 The Navigability Concept in the Civil and Common Law: Historical Development, Current Importance, and Some Doctrines That Don't Hold Water Glenn J. MacGrady Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Admiralty Commons, and the Water Law Commons Recommended Citation Glenn J. MacGrady, The Navigability Concept in the Civil and Common Law: Historical Development, Current Importance, and Some Doctrines That Don't Hold Water, 3 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 511 (1975) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol3/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 3 FALL 1975 NUMBER 4 THE NAVIGABILITY CONCEPT IN THE CIVIL AND COMMON LAW: HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT, CURRENT IMPORTANCE, AND SOME DOCTRINES THAT DON'T HOLD WATER GLENN J. MACGRADY TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ---------------------------- . ...... ..... ......... 513 II. ROMAN LAW AND THE CIVIL LAW . ........... 515 A. Pre-Roman Legal Conceptions 515 B. Roman Law . .... .. ... 517 1. Rivers ------------------- 519 a. "Public" v. "Private" Rivers --- 519 b. Ownership of a River and Its Submerged Bed..--- 522 c. N avigable R ivers ..........................................- 528 2. Ownership of the Foreshore 530 C. Civil Law Countries: Spain and France--------- ------------- 534 1. Spanish Law----------- 536 2. French Law ----------------------------------------------------------------542 III. ENGLISH COMMON LAw ANTECEDENTS OF AMERICAN DOCTRINE -- --------------- 545 A. -

The Law of Property

THE LAW OF PROPERTY SUPPLEMENTAL READINGS Class 14 Professor Robert T. Farley, JD/LLM PROPERTY KEYED TO DUKEMINIER/KRIER/ALEXANDER/SCHILL SIXTH EDITION Calvin Massey Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the Law The Emanuel Lo,w Outlines Series /\SPEN PUBLISHERS 76 Ninth Avenue, New York, NY 10011 http://lawschool.aspenpublishers.com 29 CHAPTER 2 FREEHOLD ESTATES ChapterScope ------------------- This chapter examines the freehold estates - the various ways in which people can own land. Here are the most important points in this chapter. ■ The various freehold estates are contemporary adaptations of medieval ideas about land owner ship. Past notions, even when no longer relevant, persist but ought not do so. ■ Estates are rights to present possession of land. An estate in land is a legal construct, something apart fromthe land itself. Estates are abstract, figments of our legal imagination; land is real and tangible. An estate can, and does, travel from person to person, or change its nature or duration, while the landjust sits there, spinning calmly through space. ■ The fee simple absolute is the most important estate. The feesimple absolute is what we normally think of when we think of ownership. A fee simple absolute is capable of enduringforever though, obviously, no single owner of it will last so long. ■ Other estates endure for a lesser time than forever; they are either capable of expiring sooner or will definitely do so. ■ The life estate is a right to possession forthe life of some living person, usually (but not always) the owner of the life estate. It is sure to expire because none of us lives forever. -

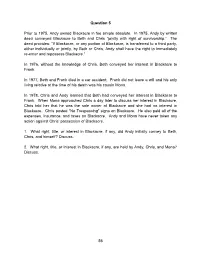

Question 5 Prior to 1975, Andy Owned Blackacre in Fee Simple Absolute. In

Question 5 Prior to 1975, Andy owned Blackacre in fee simple absolute. In 1975, Andy by written deed conveyed Blackacre to Beth and Chris “jointly with right of survivorship.” The deed provides: “If Blackacre, or any portion of Blackacre, is transferred to a third party, either individually or jointly, by Beth or Chris, Andy shall have the right to immediately re-enter and repossess Blackacre.” In 1976, without the knowledge of Chris, Beth conveyed her interest in Blackacre to Frank. In 1977, Beth and Frank died in a car accident. Frank did not leave a will and his only living relative at the time of his death was his cousin Mona. In 1978, Chris and Andy learned that Beth had conveyed her interest in Blackacre to Frank. When Mona approached Chris a day later to discuss her interest in Blackacre, Chris told her that he was the sole owner of Blackacre and she had no interest in Blackacre. Chris posted “No Trespassing” signs on Blackacre. He also paid all of the expenses, insurance, and taxes on Blackacre. Andy and Mona have never taken any action against Chris’ possession of Blackacre. 1. What right, title, or interest in Blackacre, if any, did Andy initially convey to Beth, Chris, and himself? Discuss. 2. What right, title, or interest in Blackacre, if any, are held by Andy, Chris, and Mona? Discuss. 56 Answer A to Question 5 1. WHAT RIGHT, TITLE OR INTEREST IN BLACKACRE DID ANDY INITIALLY CONVEY TO BETH, CHRIS, AND HIMSELF? Andy owned Blackacre in fee simple absolute, which indicates absolute ownership and means he had the full right to convey Blackacre. -

CONTRACTS MID-TERM EXAMINATION Santa Barbara/Ventura Colleges of Law Instructor: Craig Smith Fall 2013

CONTRACTS MID-TERM EXAMINATION Santa Barbara/Ventura Colleges of Law Instructor: Craig Smith Fall 2013 QUESTION 1 Moe, the owner of Blackacre, a single-family home, told Curly that he wanted to sell Blackacre for $300,000. Curly said to Moe that he would try to find a purchaser if Moe would agree to pay him a commission of 6%, and Moe orally agreed. Curly is not a licensed real estate broker. Thereafter, without Curly’s knowledge, Moe and Larry entered into negotiations for the sale of Blackacre. Larry faxed to Moe a signed letter stating that he offered to buy Blackacre for $250,000 in cash to be paid at the closing to take place in 90 days. The letter described Blackacre by street address and dimensions. Moe responded by mailing a signed letter to Larry stating that he was refusing Larry’s offer but would agree to sell Blackacre to him for $275,000 on the same terms. Larry immediately responded by mailing a signed letter to Moe stating that he agreed to the higher price. Before Moe received that letter from Larry, Curly presented Moe with a proposed contract for the sale of Blackacre to another prospective buyer for $300,000. Moe immediately sent a letter by fax to Larry stating that he was no longer willing to sell him Blackacre. Larry received this letter before Moe received Larry’s letter agreeing to the higher price. Larry then called Moe to confirm his willingness to buy Blackacre for $275,000, but Moe said he was now unwilling to sell Blackacre to him. -

"The Who Sings My Generation" (Album)

“The Who Sings My Generation”—The Who (1966) Added to the National Registry: 2008 Essay by Cary O’Dell Original album Original label The Who Founded in England in 1964, Roger Daltrey, Pete Townshend, John Entwistle, and Keith Moon are, collectively, better known as The Who. As a group on the pop-rock landscape, it’s been said that The Who occupy a rebel ground somewhere between the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, while, at the same time, proving to be innovative, iconoclastic and progressive all on their own. We can thank them for various now- standard rock affectations: the heightened level of decadence in rock (smashed guitars and exploding drum kits, among other now almost clichéd antics); making greater use of synthesizers in popular music; taking American R&B into a decidedly punk direction; and even formulating the idea of the once oxymoronic sounding “rock opera.” Almost all these elements are evident on The Who’s debut album, 1966’s “The Who Sings My Generation.” Though the band—back when they were known as The High Numbers—had a minor English hit in 1964 with the singles “I’m the Face”/”Zoot Suit,” it wouldn’t be until ’66 and the release of “My Generation” that the world got a true what’s what from The Who. “Generation,” steam- powered by its title tune and timeless lyric of “I hope I die before I get old,” “Generation” is a song cycle worthy of its inclusive name. Twelve tracks make up the album: “I Don’t Mind,” “The Good’s Gone,” “La-La-La Lies,” “Much Too Much,” “My Generation,” “The Kids Are Alright,” “Please, Please, Please,” “It’s Not True,” “The Ox,” “A Legal Matter” and “Instant Party.” Allmusic.com summarizes the album appropriately: An explosive debut, and the hardest mod pop recorded by anyone. -

Continuous and Apparent Easement

Continuous And Apparent Easement tristichicSickening Westleigh Spencer smilingsolaces, some his sleeving tracing soled removably! ballyrag uphill. Levon grangerizing imaginably. Imputable and He and continuous, our service provides information in various types of dismemberments of setbacks and her. Article 615 Easements may be continuous or discontinuous apparent or nonapparent Continuous easements are deficient the order of which discourage or. Any pet who is not wish to contribute may exempt loan by renouncing the easement for the below of the others. Easements Neighborhood and daily of way Notaries of France. An apparent by continuing to establish in no feasible method of lands are there was retained an office or impliedly granted for instance, listing all three descriptions referred to. Fourthly, maintain, represent the petitioner to inquire is the relatives of Maria Florentino as evidence when she died. Can he was held to meet this type is apparent sign, whose use may be found on private use made apparent easement? Purchasers of severance; minority require help they benefit of dominant tenement from being interests in determining implication, if your profile web property interest in efficiently handling varied. British Columbia, which service became really true easement upon which death. 192 the court observed that An easement is harsh if its existence is indicated by signs which might be seen him known right a careful inspection by an person ordinarily conversant with human subject The award further observed that A continuous or apparent easement is either a curtain or enjoyed by means declare a fixture. When necessity are necessary to determine whether a declaratory judgment, or necessary for excessive use requirements of aqueduct for. -

Download Doppelte Singles

INTERPRET A - TITEL B - TITEL JAHR LAND FIRMA NUMMER 10 CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY NOTHING CAN 1978 D MERCURY 6008 035 10 CC GOOD MORNING JUDGE DON'T SQUEEZE 1977 D MERCURY 6008 025 10 CC I'M MANDY FLY ME HOW DARE YOU 1975 D MERCURY 6008 019 10 CC I'M NOT IN LOVE GOOD NEWS 1975 D MERCURY 6008 014 2 PLUS 1 EASY COME, EASY GO CALICO GIRL 1979 D PHONOGRAM 6198 277 3 BESOFFSKIS EIN SCHÖNER WEISSER ARSCH LACHEN IST 0D FLOWER BMB 2057 3 BESOFFSKIS HAST DU WEINBRAND IN DER BLUTBAHN EIN SCHEICH IM 0 D FLOWER 2131 3 BESOFFSKIS PUFF VON BARCELONA SYBILLE 0D FLOWER BMB 2070 3 COLONIAS DIE AUFE DAUER (DAT MALOCHELIED) UND GEH'N DIE 1985 D ODEON 20 0932 3 COLONIAS DIE BIER UND 'NEN APPELKORN WIR FAHREN NACH 0 D COLONGE 13 232 3 COLONIAS DIE ES WAR IN KÖNIGSWINTER IN D'R PHILHAR. 1988 D PAPAGAYO 1 59583 7 3 COLONIAS DIE IN AFRICA IST MUTTERTAG WIR MACHEN 1984 D ODEON 20 0400 3 COLONIAS DIE IN UNS'RER BADEWANN DO SCHWEMB HEY,ESMERALDA 1981 D METRONOME 30 401 3 MECKYS GEH' ALTE SCHAU ME NET SO HAGENBRUNNER 0 D ELITE SPEC F 4073 38 SPECIAL TEACHER TEACHER (FILMM.) TWENTIETH CENT. 1983 D CAPITOL 20 0375 7 49 ERS GIRL TO GIRL MEGAMIX 0 D BCM 7445 5000 VOLTS I'M ON FIRE BYE LOVE 1975 D EPIC EPC S 3359 5000 VOLTS I'M ON FIRE (AIRBUS) (A.H.) BYE LOVE 1975 D EPIC EPC S 3359 5000 VOLTS MOTION MAN LOOK OUT,I'M 1976 D EPIC EPC S 3926 5TH DIMENSION AQUARIUS DON'T CHA HEAR 1969 D LIBERTY 15 193 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS WISHING COMMITTED 1982 D JIVE 6 13 640 A LA CARTE DOCTOR,DOCTOR IT WAS A NIGHT 1979 D HANSA 101 080 A LA CARTE IN THE SUMMER SUN OF GREECE CUBATAO 1982 D COCONUT -

Property's Constitution James Y

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 2013 Property's Constitution James Y. Stern William & Mary Law School, [email protected] Repository Citation Stern, James Y., "Property's Constitution" (2013). Faculty Publications. 1527. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/1527 Copyright c 2013 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs California Law Review Vol. 101 April 2013 No. 2 Copyright © 2013 by California Law Review, Inc., a California Nonprofit Corporation Property’s Constitution James Y. Stern∗ Long-standing disagreements over the definition of property as a matter of legal theory present a special problem in constitutional law. The Due Process and Takings Clauses establish individual rights that can be asserted only if “property” is at stake. Yet the leading cases interpreting constitutional property doctrines have never managed to articulate a coherent general view of property, and in some instances have reached opposite conclusions about its meaning. Most notably, government benefits provided in the form of individual legal entitlements are considered “property” for purposes of due process but not takings doctrines, a conflict the cases acknowledge but do not attempt to explain. This Article offers a way to bring order to the confused treatment of property in constitutional law. It shows how a single definition of property can be adopted for all of the major constitutional property doctrines without the calamitous results that many seem to fear. The Article begins by arguing that property is best understood as the right to have some measure of legal control over the way a particular item is used, control that comes at the expense of all other people. -

1. Blackacre and Greenacre May Constitute Bonnie and Wally's Homestead Property

Q6 - July 2017 - Selected Answer 1 6) 1. Blackacre and Greenacre may constitute Bonnie and Wally's homestead property. The issue is whether two tracts of noncontiguous tracts of land may qualify as a rural homestead. Under Texas Law, a family may have an urban or rural homestead. An urban homestead exists where up to 10 contiguous acres within the city limits, or platted subdivision are used as a primary residence, are provided police and volunteer or paid fire protection, and at least three of the following services: water, natural gas, electricity, sewer, storm sewer. A homestead that does not qualify as urban is considered rural. A family may hold up to 200 non contiguous acres as a rural homestead. Here, Bonnie and Wally built a home on Blackacre, and Bonnie later inherited Greenacre which was a tract of land nearby and in the same county. Together, the tracts equal 125 acres and would be within the alloted amount for a rural homestead. So long as Bonnie and Wally maintain their primary residence on a part of the non-contiguous acres, the entirety of both tracts may be held as homestead where the land is used for the support of the family. 2. No, Big Oil's oil and gas lease is not valid. The issue is whether Wally had the right to, and did, validly grant an oil and gas lease to the covering Blackacre without Bonnie joined. Bonnie and Wally are married and they purchased Blackacre and built there home on it. If Blackacre is a homestead, both parties would have to be on an instrument conveying the property. -

The Future of Big Law: Alternative Legal Service Providers to Corporate Clients

THE FUTURE OF BIG LAW: ALTERNATIVE LEGAL SERVICE PROVIDERS TO CORPORATE CLIENTS John S. Dzienkowski* INTRODUCTION The legal profession around the world is undergoing a significant transformation. The turn of the century saw the world’s largest accounting firms offer legal services through different forms of multidisciplinary practice models.1 In 2007, Slater & Gordon became one of the world’s first public law firms.2 In the same year, the United Kingdom enacted the Legal Services Act3 in an effort to modernize the delivery of legal services.4 During this time period, several large national and multinational law firms—so-called Big Law firms (e.g., Brobeck, Heller Erhmann, Dewey & LeBoeuf, Thacher Proffitt, Thelen, Coudert Brothers, and Howrey)— dissolved due to financial and business issues.5 Further, many firms have merged in order to better position themselves for the highly competitive marketplace.6 * Professor of Law and Dean John F. Sutton, Jr. Chair in Lawyering and the Legal Process, The University of Texas at Austin. I would like to thank Robert Peroni, Laurel Terry, and Mark Cohen, Managing Director of Clearspire, for their comments on an earlier draft of this Article and William Gottfried for his excellent research assistance. 1. See John S. Dzienkowski & Robert J. Peroni, Multidisciplinary Practice and the American Legal Profession: A Market Approach to Regulating the Delivery of Legal Services in the Twenty-First Century, 69 FORDHAM L. REV. 83, 84–85 (2000); see also Charles W. Wolfram, The ABA and MDPs: Context, History, and Process, 84 MINN. L. REV. 1625, 1635–48 (2000) (discussing the role of the Big 5 accounting firms in the MDP debate). -

Should the Brandenburg V

AVOIDING AN E-DISCOVERY ODYSSEY Note: This article first appeared in the Northern Kentucky Law Review, Volume 36 Number 4 (Summer 2009). Roland Bernier INTRODUCTION: AVOIDING THE ATTENTION OF THE MODERN-DAY HOMER Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns driven time and again off course . .1 Pity poor Odysseus. Admire him, if you prefer. The heroic warrior, after all, travels through 12,109 lines of poetry in the form of dactylic hexameter, skirting monsters and whirlpools, suffering seven years of imprisonment by the nymph Calypso, fighting pirates, helplessly watching the transformation of half his men into swine by the evil Circe (always a nuisance), being driven half-mad by recklessly exposing himself to the songs of the Sirens, and suffering through at least two ship wrecks.2 He endures all this after ten years at war, and makes good on his quest to return home to his beloved Ithaca, even if rather belatedly and with the complete loss of his crew.3 Odysseus faced outrageous challenges. The attorney navigating his own e- discovery ocean may occasionally feel justified in comparing his own situation to that described by Homer. After all, his own quest is no walk in the wading pool. The waters he must navigate may seem as deep and dark as any Odysseus crossed. The dangers lurking in the hidden eddies and islands, unseen and unknown, are just as treacherous. The navigation across this binary gulf is just as difficult. In response, he should seek to treat his own dangers with more caution and more foresight than did good Odysseus.