The History of Clementhorpe Nunnery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norman Rule Cumbria 1 0

NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY N O R M A N R U L E I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE Pr o f essor of Diplomat i c , U n i v e r sity of Oxfo r d President of the Surtees Society A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Tract Series Vol. XXI C&W TRACT SERIES No. XXI ISBN 1 873124 43 0 Published 2006 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the Council of the Society for inviting me, as president of the Surtees Society, to address the Annual General Meeting in Carlisle on 9 April 2005. Several of those who heard the paper on that occasion have also read the full text and allowed me to benefit from their comments; my thanks to Keith Stringer, John Todd, and Angus Winchester. I am particularly indebted to Hugh Doherty for much discussion during the preparation of this paper and for several references that I should otherwise have missed. In particular he should be credited with rediscovering the writ-charter of Henry I cited in n. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION. FORMER publications * of the Camden Society have brought before our notice Richard Duke of Gloucester, as continually engaged in the intrigues of a court or the storms of civil war, while for four centuries both his person and character have been the theme of almost universal vituperation. Into these subjects it is not the province of the editor of the present volume to enter; and, in truth, there is now the less occasion for it, since the volumes of Miss Halsted have appeared in the field of literature. This talented and zealous writer has adduced a host of authorities, apparently proving that his personal deformity existed but in the libels of an opposing faction, perpetuated in the pages of the poet and the novelist; while at the same time her researches seem to throw such light over the darker shades in his chequered career, as to induce the strongest presumption that he was not guilty of, or accessory to, those startling crimes which have been charged to his account. The limits, however, of the brief introduction allotted to this work, compel us to turn our attention from scenes of battle and of blood to other, and to us more interesting portions of his history. When, on the partition f of Warwick's vast domains between the sister heiresses, the lordship and manor of Middleharn, with its ancestral castle, became the fair heritage of Gloucester in * Historic of the Arrival of Edward IV. ; Warkworth's Chronicle ; and Polydore Vergil; being Nos. I. X. and XXVIII. of the Camden Society's publications. -

Official Act of Consecration to the Immaculate

COMFORTER OF THE AFFLICTED Pray for Us 0//icial cAct o/ Concecration OF THE DOMINICAN ORDER TO THE .!Jmmaculate J.leart o/ .Atarg QUEEN OF THE MOST HOLY ROSARY, Help of Christians, Refuge of the llUman race, Victress in all (I God's battles, we, suppliantly and with great confidence, not in our own merits but solely because of the immense goodness of thy motherly heart, prostrate ourselves before thy throne begging mercy, grace, and timely aid. To thee and to thy Immaculate Heart we bind and conse crate ourselves anew, in union with our Holy Mother, the 01Urch, the Mystical Body of Christ. Once again we proclaim thee the Queen of our Order-the Order truly, which thy son, Dominic, 240 Dominicana founded to preach, through thy aid, the word of truth everywhere for the salvation of souls; the Order which thou has chosen as a beautiful, fragrant, and splendid garden of delights; the Order in which the light of wisdom ought so splendidly to shine that its members might bestow on others the fruit of their contempla tion, not only by courageously uprooting heresy but also by sow ing the seeds of virtue everywhere; the Order which during the course of centuries has gloried in thy scapular and in thy most holy Rosary, which daily and in the hour of death devoutly and confidently salutes thee as advocate in those words most sublime: Hail Holy Queen, Mother of Mercy. To thee, 0 Mary, and to thy Immaculate Heart we conse crate today this religious house, this community, that thou might be truly its Queen; that perfect observance, the love of thy Son in the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar, the love of thy praise, and the love of St. -

62-68 Low Petergate, York

YORK ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST 62-68 LOW PETERGATE, YORK Principal author Ben Reeves WEB PUBLICATION Report Number AYW7 2006 YORK ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST York Archaeological Trust undertakes a wide range of urban and rural archaeological consultancies, surveys, evaluations, assessments and excavations for commercial, academic and charitable clients. We manage projects, provide professional advice and fieldwork to ensure a high quality, cost effective archaeological and heritage service. Our staff have a considerable depth and variety of professional experience and an international reputation for research, development and maximising the public, educational and commercial benefits of archaeology. Based in York, Sheffield, Nottingham and Glasgow the Trust’s services are available throughout Britain and beyond. York Archaeological Trust, Cuthbert Morrell House, 47 Aldwark, York YO1 7BX Phone: +44 (0)1904 663000 Fax: +44 (0)1904 663024 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.yorkarchaeology.co.uk © 2018 York Archaeological Trust for Excavation and Research Limited Registered Office: 47 Aldwark, York YO1 7BX A Company Limited by Guarantee. Registered in England No. 1430801 A registered Charity in England & Wales (No. 509060) and Scotland (No. SCO42846) York Archaeological Trust i CONTENTS ABOUT THIS PDF ..............................................................................................................................................II 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... -

Pedigrees of the County Families of Yorkshire

94i2 . 7401 F81p v.3 1267473 GENEALOGY COLLECTION 3 1833 00727 0389 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center http://www.archive.org/details/pedigreesofcount03fost PEDIGREES YORKSHIRE FAMILIES. PEDIGREES THE COUNTY FAMILIES YORKSHIRE COMPILED BY JOSEPH FOSTER AND AUTHENTICATED BY THE MEMBERS, OF EACH FAMILY VOL. fL—NORTH AND EAST RIDING LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED FOR THE COMPILER BY W. WILFRED HEAD, PLOUGH COURT, FETTER LANE, E.G. LIST OF PEDIGREES.—VOL. II. t all type refer to fa Hies introduced into the Pedigrees, i e Pedigree in which the for will be found on refer • to the Boynton Pedigr ALLAN, of Blackwell Hall, and Barton. CHAPMAN, of Whitby Strand. A ppleyard — Boynton Charlton— Belasyse. Atkinson— Tuke, of Thorner. CHAYTOR, of Croft Hall. De Audley—Cayley. CHOLMELEY, of Brandsby Hall, Cholmley, of Boynton. Barker— Mason. Whitby, and Howsham. Barnard—Gee. Cholmley—Strickland-Constable, of Flamborough. Bayley—Sotheron Cholmondeley— Cholmley. Beauchamp— Cayley. CLAPHAM, of Clapham, Beamsley, &c. Eeaumont—Scott. De Clare—Cayley. BECK.WITH, of Clint, Aikton, Stillingfleet, Poppleton, Clifford, see Constable, of Constable-Burton. Aldborough, Thurcroft, &c. Coldwell— Pease, of Hutton. BELASYSE, of Belasvse, Henknowle, Newborough, Worlaby. Colvile, see Mauleverer. and Long Marton. Consett— Preston, of Askham. Bellasis, of Long Marton, see Belasyse. CLIFFORD-CONSTABLE, of Constable-Burton, &c. Le Belward—Cholmeley. CONSTABLE, of Catfoss. Beresford —Peirse, of Bedale, &c. CONSTABLE, of Flamborough, &c. BEST, of Elmswell, and Middleton Quernhow. Constable—Cholmley, Strickland. Best—Norcliffe, Coore, of Scruton, see Gale. Beste— Best. Copsie—Favell, Scott. BETHELL, of Rise. Cromwell—Worsley. Bingham—Belasyse. -

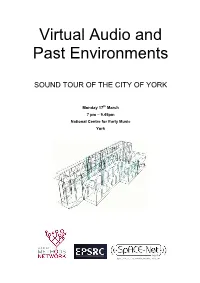

Sound Tour Programme and Guide

Virtual Audio and Past Environments SOUND TOUR OF THE CITY OF YORK Monday 17 th March 7 pm – 9.45pm National Centre for Early Music York SCHEDULE 7pm STATION 1: National Centre for Early Music Croisda Liom A Cadal from Dusk Songs by Kerry Andrew performed by the Ebor Singers [Follow red line on map and proceed to]: 7.45pm STATION 2: Bedern Hall A Sense of Place [Revisited II]: Damian Murphy , Mark Hildred and John Oxley. [Follow purple line on map and proceed to]: 8.25pm STATION 3: Number 3, Blake Street States of Being: Angie Atmadjaja [Follow green line on map and proceed to]: 9pm STATION 4: York Minster Service of Compline - Quire: including introit and anthems sung by the Ebor Singers Private Performance - Chapter House: Croisda Liom A Cadal from Dusk Songs by Kerry Andrew from 9.45pm (approx) Drinks at the Yorkshire Terrier – Stonegate Station 1: National Centre for Early Music The National Centre for Early Music is created from the medieval church of St Margaret’s - an important historic church, which lies within the City Walls and which was empty since the 1960s. Used as a theatrical store by the York Theatre Royal up until 1996, St Margaret’s was one of the last two churches in the city of York that remained un-restored. The church is of considerable architectural significance - its most distinguishing features being an ornate Romanesque porch from the 12th century, with carvings of mythological beasts - and an unusual brick bell tower. The National Centre for Early Music is administered by a registered charity, the York Early Music Foundation. -

TRHS Fourth Series

Transactions of the Royal Historical Society FOURTH SERIES Volume I (1918) Hudson, Revd. William, ‘Traces of Primitive Agricultural Organisation, as suggested by a Survey of the Manor of Martham, Norfolk (1101-1292)’, pp. 28-28 Green, J.E.S., ‘Wellington, Boislecomte, and the Congress of Verona (1822)’, pp. 59-76 Lubimenko, Inna, ‘The Correspondence of the First Stuarts with the First Romanovs’, pp. 77-91 Methley, V.M., ‘The Ceylon Expedition of 1803’, pp. 92-128 Newton, A.P., ‘The Establishment of the Great Farm of the English Customs’, pp. 129- 156 Plucknett, Theodore F.T., ‘The Place of the Council in the Fifteenth Century (Alexander Prize Essay, 1917)’, pp. 157-189 Egerton, H.E., ‘The System of British Colonial Administration of the Crown Colonies in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, Compared with the System Prevailing in the Nineteenth Century’, pp. 190-217 Amery, L.S., ‘The Constitutional Development of South Africa’, pp. 218-235 Wrong, E.M., ‘The Constitutional Development of Canada’, pp. 236-254 Volume II (1919) Oman, C.W.C., ‘Presidential Address: National Boundaries and Treaties of Peace’, pp. 1- 19 ‘British and Allied Archives during the War (England, Scotland, Ireland, United States of America, France, Italy)’, pp. 20-58 Graham, Rose, ‘The Metropolitical Visitation of the Diocese of Worcester by Archbishop of Winchelsey’, pp. 59-93 Seton, W.W., ‘The Relations of Henry, Cardinal York with the British Government’, pp. 94-112 Davies, Godfrey, ‘The Whigs and the Peninsula War’, pp. 113-131 Gregory, Sir R.A., ‘Science in the History of Civilisation’, pp. 132-149 Omond, G.W.T., ‘The Question of The Netherlands in 1829-1830’, pp. -

York-Cat-Trail-Leaflet.Pdf

THE YORK CAT STORY Cats have played a part in York’s history and luck has been linked with them since records began. Cats always land on their feet and having nine lives is a piece of luck that we can all relate to. FREE York Glass is the home of York Lucky Cats where we celebrate the York Cat story. Statues of cats have been placed on buildings in York for around two Centuries, although statues since removed or rotted are thought to date from medieval times. The original cat statues were placed on buildings to York Glass is found in a beautiful frighten away rats and mice which can carry plague listed building in the middle of and illness. They were also thought to ward off Shambles which is at the heart of ‘Olde’ York. The traditional shop window displays a vivid, wandering evil spirits and generally to bestow good PRESENTS luck and good health on citizens who needed feline colourful and changing mixture of products. We sell gifts, friends to ensure a good nights sleep in old and predominantly in Glass for all occasions. Handmade glass jewellery with Murano beads, friendship globes, spun glass, temptingly chewy timber framed buildings! fused glass, crystal glass, glass Christmas trees, glass York Lucky Cats are small hand-made flowers, glass hearts, glass nail files! Glass is our thing. glass cats which are available in twelve We are a small group and are passionate about offering THE jewel-like colours that match the gem the best products at competitive prices and we pack it with care too! stones considered lucky for each www. -

Pathfinder Newsletter

Pathfinder Newsletter Providing an excellent education from age 2 to 19 SUMMER 2021 Dear Parents and Carers, We’ve made it to the end of another challenging but Summer holiday activities successful academic year. Thank you for all the support you have given our schools, particularly since students returned to Ignite Sports Coaching summer holiday club is their classrooms at the beginning of March. running at Acomb Primary School on the weeks Despite the challenges we have faced during the past 18 beginning: months, our schools have a lot to celebrate, be proud of and Monday 26 July look forward to next year. The following are just some of the things which have happened across the trust this term. Monday 2 August Monday 9 August Earlier this month, Clifton with Rawcliffe Primary School had a Monday 16 August visit from Ofsted. This was a fantastic opportunity for the staff Monday 23 August and students to share the strengths of the school, particularly the excellent work being done across the curriculum and the For more information and to book a place, please focus on behaviour and attitudes to learning. We look forward visit: www.ignitesportscoaching.co.uk/book-now to sharing more information when the full report is published. We are delighted to announce that Hempland Primary School has made it onto the government’s school rebuilding Total Sports summer holiday club for children programme. Hempland is one of fifty schools across the aged 5 to 12 is running at the following schools country which will benefit from new and improved school across York: buildings and facilities. -

Minutes of the Beeford Parish Council Meeting on Monday 9Th December 2019 at 7.00 Pm at the Beeford Community Centre

Minutes of the Beeford Parish Council Meeting On Monday 9th December 2019 at 7.00 pm At the Beeford Community Centre Present: Chairman Keith McCloud, Vice Chair Alan Turner Councillors Hazel Adamson, Brian Jackson, Ian Sawyer, Barbara Smithson, John Sowersby, Rosalind Turner, Colin Wilburn, Clerk to Parish Council Anne McCloud Ward Councillor Jane Evison, Members of the Public 1. Apologies for Absence: Councillors Clark Robson, Rita Scurr Ward Councillors Jonathan Owen and Paul Lisseter. 2. Declaration of Interest - No declarations of interest were made. 3. To accept minutes of the meeting held on 11th November 2019. Proposed Cllr Jackson Seconded Cllr A Turner Agreed 4. Matters arising a. Wayne Goodwin, Community Speed Watch Coordinator gave a presentation in relation to Community Speed Watch which is a community initiative between residents and Humberside Police to volunteer and monitor vehicle speeds using speed detection devises. The aim of the scheme is to improve road safety, driver behaviour and reduce speeding and injuries and deaths on our roads. 16 Parishes are already taking part in this scheme, Kilham being the closest village. Full details can be found on the Parish Council website and will also be published in the Beeford Buzz. b. Concerns have been raised by residents in relation to boundary fencing/access gates being used by work vehicles entering and exiting a neighbouring property via Mill View Crescent. The ERYCC have been made aware of this and they will be making further enquiries and will keep the Parish Council updated. 5. Correspondence a. Notification of Temporary road closures from Highways ERYCC in relation to Woodnook Road, Bewholme, Skipsea Lane, Nunkeeling Road, Dunnington to allow for resurfacing works to be carried out throughout December and January 2020. -

Durham Cathedral: Building Time Line with Significant Historic Events

Durham Cathedral: Building time line with significant historic events Pre Conquest 634 Oswald reclaimed the Kingdom of Northumbria from Penda of Mercia, reigning for 9 years as a Christian King. He brought Aidan from Iona and installed him as first Bishop of Lindisfarne. 641 Oswiu, brother of Oswald was made King of Northumbria after Penda defeated and killed Oswald. Oswiu ruled for 28 years. 687 Death of Cuthbert, the ascetic Prior and later Bishop of Lindisfarne (born 625). After his death the monks at Lindisfarne elevated him to sainthood in 698. The Lindisfarne Gospels are completed around this time. 793 Following the Viking attack on Holy Island and the sacking of the monastery there, the monks moved to the old Roman town of Chester le Street in 795, carrying Cuthbert’s coffin to the new priory site. 865-8 First Viking invasion by Danes, using the Humber, Trent and Ouse, they penetrated both Northumbria and Mercia appropriating territory for settlement. The Anglo Saxons called them the ‘heathen army’. 954 King Eadred conquers the Scandinavian Kingdom of York, Yorkshire and Lancashire are carved out of Northumbria, and Northumbria’s southern boundary moves from the Humber to the Tees. 995 Cuthbert's community of monks see the defensive potential of the rocky site at Durham situated on a loop of the River Wear and decide to move their church there and establish an Episcopal See under Bishop Aldhun. The first church constructed is of wood, but it is rebuilt in 998 in stone. 1020 The church is again rebuilt as a much larger stone Cathedral, completed in 1042 in the Saxon style, known as the ‘White Church’. -

Ricardian Bulletin Edited by Elizabeth Nokes and Printed by St Edmundsbury Press

Ricardian Bulletin Magazine of the Richard III Society ISSN 0308 4337 Winter 2003 Richard III Society Founded 1924 In the belief that many features of the traditional accounts of the character and career of Richard III are neither supported by sufficient evidence nor reasonably tenable, the Society aims to promote in every possible way research into the life and times of Richard III, and to secure a re-assessment of the material relating to this period and of the role in English history of this monarch Patron HRH The Duke of Gloucester KG, GCVO Vice Presidents Isolde Wigram, Carolyn Hammond, Peter Hammond, John Audsley, Morris McGee Executive Committee John Ashdown-Hill, Bill Featherstone, Wendy Moorhen, Elizabeth Nokes, John Saunders, Phil Stone, Anne Sutton, Jane Trump, Neil Trump, Rosemary Waxman, Geoffrey Wheeler, Lesley Wynne-Davies Contacts Chairman & Fotheringhay Co-ordinator: Phil Stone Research Events Adminstrator: Jacqui Emerson 8 Mansel Drive, Borstal, Rochester, Kent ME1 3HX 5 Ripon Drive, Wistaston, Crewe, Cheshire CW2 6SJ 01634 817152; e-mail: [email protected] Editor of the Ricardian: Anne Sutton Ricardian & Bulletin Back Issues: Pat Ruffle 44 Guildhall Street, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk IP33 1QF 11 De Lucy Avenue, Alresford, Hants SO24 9EU e-mail: [email protected] Editor of Bulletin Articles: Peter Hammond Sales Department: Time Travellers Ltd. 3 Campden Terrace, Linden Gardens, London W4 2EP PO Box 7253, Tamworth, Staffs B79 9BF e-mail: [email protected] 01455 212272; email: [email protected] Librarian