Explaining the Joy in the Text of Jim Bouton's Ball Four: a Study In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baseball Under Glass

Jokester Klein mined gold in Minoso’s sore body parts By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Tuesday, August 8, 2017 Robert Klein loves self-generated sound effects and body English em- phasis in his comic act. But like the veteran pitcher nearing 40, the 75-year-old jokester can't summon his vintage fastball when he needs it. In this case, reviving his old Minnie Minoso on-stage thread. “I did a routine about him holding the record being hit by pitched balls,” Klein said of the late, fearless White Sox great. “So I made up a fictitious (slapping) noise for being hit by a Robert Klein once had Minnie Minoso as a sound- pitch. I can’t do that noise anymore of effects, body English part of his act. a ball being hit. My tongue won’t op- erate like that. “When I did the routine, it was Chicago (tongue slap), St. Louis (tongue slap), and each time I’d get hit in the head. His (HBP) record was broken by Ron Hunt. I said they’d meet once a year together and show two goofy guys who were hit in the head too many times.” Klein then followed Minoso to the end of his career…whenever. “It was a nice gesture when the Sox brought him back for technically a fifth decade (1980),” he said. “A guy like him, he could have made his debut earlier (if not for the col- or line).” Klein did not channel Minoso from second-hand information. He watched Minnie in his Sox prime in the 1950s at Yankee Stadium, his home away from home in his native Bronx. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Letter to collector and introduction to catalog ........................................................................................ 4 Auction Rules ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Clean Sweep All Sports Affordable Autograph/Memorabilia Auction Day One Wednesday December 11 Lots 1 - 804 Baseball Autographs ..................................................................................................................................... 6-43 Signed Cards ................................................................................................................................................... 6-9 Signed Photos.................................................................................................................................. 11-13, 24-31 Signed Cachets ............................................................................................................................................ 13-15 Signed Documents ..................................................................................................................................... 15-17 Signed 3x5s & Related ................................................................................................................................ 18-21 Signed Yearbooks & Programs ................................................................................................................. 21-23 Single Signed Baseballs ............................................................................................................................ -

Jim Bouton's Ball Four Changes Baseball's Image

Undergraduate Review Volume 1 Issue 1 Article 8 1986 Myth and America's National Pastime: Jim Bouton's Ball Four Changes Baseball's Image Steven B. Stone '86 Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/rev Recommended Citation Stone '86, Steven B. (1986) "Myth and America's National Pastime: Jim Bouton's Ball Four Changes Baseball's Image," Undergraduate Review: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/rev/vol1/iss1/8 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Stone '86: Myth and America's National Pastime: Jim Bouton's Ball Four Chan Fugitive in Brink's Case," NIT, May 25, :night-Ridder Newspapers), Holmesburg 'he New York Review of Books, Sept. 22, Myth and America's National Pastime: Jim Bouton's BaH Four Changes Baseball's Image Steven B. Stone IAIsweek, July 21, 1980, p. 35. lewsweek, Dec. 15, 1980, p. -

On 14-7 Road Mark

C-1 Stranahan Has 72 ftienirtg CLASSIFIED ffiaf SPORTS AMUSEMENTS In British Open Golf WASHINGTON, D. C., WEDNESDAY, JULY 4, 1956 ** HOYLAKE, England, July 4 The defending champion, four i UP).—Frank Stranahan, the To- under level fours through the j ledo, Ohio, muscle man. shot a 16th, took bogey fives on the 17th one-over-par 72 in the first and 18th. round of the British Open golf Gene Sarazen, 54-year-old vet- -4» ’¦!"! ¦ championship today. eran from Germantown, N. Y., —1 I Reins Stranahan, who finished won the British Open in Braves Grab sec-!!who ond in the Open twice during his 1932, shot an opening round of amateur days, was the first fin- 40-38—78. isher among four Americans who j Steady on Bark Nine qualified for tournament on Sarazen took a bogey five on the 6,950-yard, par 35-36—71! - the first hole and skied to a seven Hoylake Mark course. the par four 14-7 on third. He col- On Road Welsh Champion Dennis lected birdies on the fifth and Smalldon, the first finisher of the ninth holes but bogeyed three day. shot a record-equaling 68. others to reach the turn in 40, TRIPLE BEATS RED SOX Memory of Last Argentina's Enrique Bertolino five over par. He was steadier I | had 69 and defending champion on the back nine but didn't get Stand at Home Peter Thomson of Australia a 70. another birdie until the 18th, 1 A brisk wind which started in where he sank a 10-foot putt, Senators Hit Jackpot the middle of the morning made; “That the only Only Drawback j was one I Press trouble for some of the players made all day,” he said. -

{PDF EPUB} Pinstriped Summers Memories of Yankee Seasons Past by Dick Lally Lally, Richard

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Pinstriped Summers Memories of Yankee Seasons Past by Dick Lally Lally, Richard. PERSONAL: Married Barbara Bauer (a writer; divorced). ADDRESSES: Agent —c/o Author Mail, Random House/Crown, 1745 Broadway, New York, NY 10019. CAREER: Sportswriter. WRITINGS: (With Bill Lee) The Bartender's Guide to Baseball , Warner Books (New York, NY), 1981. (With Bill Lee) The Wrong Stuff , Viking (New York, NY), 1984. Pinstriped Summers: Memories of Yankee Seasons Past , Arbor House (New York, NY), 1985. Chicago Clubs (collectors edition), Bonanza Books (New York, NY), 1991. Boston Red Sox (collectors edition), Bonanza Books (New York, NY), 1991. (With Joe Morgan) Baseball for Dummies , foreword by Sparky Anderson, IDG Books Worldwide (Foster City, IA), 1998. (With Joe Morgan) Long Balls, No Strikes: What Baseball Must Do to Keep the Good Times Rolling , Crown (New York, NY), 1999. Bombers: An Oral History of the New York Yankees , Crown (New York, NY), 2002. (With Bill Lee) Have Glove, Will Travel: The Adventures of a Baseball Vagabond , Crown (New York, NY), 2005. SIDELIGHTS: Sports writer Richard Lally focusses much of his efforts on his main passion: baseball. After collaborating with former pro player Bill Lee on Lee's autobiography, The Wrong Stuff , Lally wrote Pinstriped Summers: Memories of Yankee Seasons Past , a book that focuses on the team's history from the time the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) bought the team in 1965 until the 1982 season. During this period, the Yankees experienced great success, winning four American League pennants and two World Series. They also experience "down" years, including a last-place finish in 1966. -

Estimated Age Effects in Baseball

ESTIMATED AGE EFFECTS IN BASEBALL By Ray C. Fair October 2005 Revised March 2007 COWLES FOUNDATION DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 1536 COWLES FOUNDATION FOR RESEARCH IN ECONOMICS YALE UNIVERSITY Box 208281 New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8281 http://cowles.econ.yale.edu/ Estimated Age Effects in Baseball Ray C. Fair¤ Revised March 2007 Abstract Age effects in baseball are estimated in this paper using a nonlinear xed- effects regression. The sample consists of all players who have played 10 or more full-time years in the major leagues between 1921 and 2004. Quadratic improvement is assumed up to a peak-performance age, which is estimated, and then quadratic decline after that, where the two quadratics need not be the same. Each player has his own constant term. The results show that aging effects are larger for pitchers than for batters and larger for baseball than for track and eld, running, and swimming events and for chess. There is some evidence that decline rates in baseball have decreased slightly in the more recent period, but they are still generally larger than those for the other events. There are 18 batters out of the sample of 441 whose performances in the second half of their careers noticeably exceed what the model predicts they should have been. All but 3 of these players played from 1990 on. The estimates from the xed-effects regressions can also be used to rank players. This ranking differs from the ranking using lifetime averages because it adjusts for the different ages at which players played. It is in effect an age-adjusted ranking. -

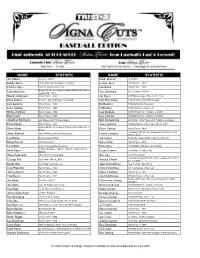

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

Dorchester Reporter “The News and Values Around the Neighborhood”

Dorchester Reporter “The News and Values Around the Neighborhood” Volume 29 Issue 43 Thursday, October 25, 2012 50¢ Lehane takes on the Roaring Twenties By Bill Forry big-studio film some day soon, man of letters since old Eddie tell their fans to chill the hell Managing Editor but any sting that Lehane Everett himself has developed out over an ill-advised Globe “South Boston punk becomes might suffer from the blunt a loyal — some might say review?) a Florida crime boss.” That’s summary is soothed by the crazed —international fan Lehane’s fan base will get how one newspaper boiled source: The New York Times base after ten books, three of bigger still with the release of down Dennis Lehane’s latest Book Review noting that his which have become celluloid “Live By Night.” In a United novel. Sure, that’s one way of latest novel has debuted at No. blockbusters at the hands of States enflamed yet again by summarizing “Live by Night,” 8 on the paper’s bestseller list. Scorsese, Eastwood, and Af- bootleggers, Tommy guns, the Roaring Twenties gangster No big surprise there. fleck. (How many other writers and flapper chicks, Lehane page-turner that will also be a Dorchester’s most celebrated have to take to Facebook to (Continued on page 17) Dennis Lehane: History calls No consensus yet on maps for City Council Competing plans will go down to the wire next week By gintautaS duMciuS nEwS Editor City councillors yesterday continued their internal debates as they worked to produce yet another map – their third this year – that would shift the boundaries of several districts for the 2013 municipal election. -

Kit Young's Sale #154

Page 1 KIT YOUNG’S SALE #154 AUTOGRAPHED BASEBALLS 500 Home Run Club 3000 Hit Club 300 Win Club Autographed Baseball Autographed Baseball Autographed Baseball (16 signatures) (18 signatures) (11 signatures) Rare ball includes Mickey Mantle, Ted Great names! Includes Willie Mays, Stan Musial, Eddie Murray, Craig Biggio, Scarce Ball. Includes Roger Clemens, Williams, Barry Bonds, Willie McCovey, Randy Johnson, Early Wynn, Nolan Ryan, Frank Robinson, Mike Schmidt, Jim Hank Aaron, Rod Carew, Paul Molitor, Rickey Henderson, Carl Yastrzemski, Steve Carlton, Gaylord Perry, Phil Niekro, Thome, Hank Aaron, Reggie Jackson, Warren Spahn, Tom Seaver, Don Sutton Eddie Murray, Frank Thomas, Rafael Wade Boggs, Tony Gwynn, Robin Yount, Pete Rose, Lou Brock, Dave Winfield, and Greg Maddux. Letter of authenticity Palmeiro, Harmon Killebrew, Ernie Banks, from JSA. Nice Condition $895.00 Willie Mays and Eddie Mathews. Letter of Cal Ripken, Al Kaline and George Brett. authenticity from JSA. EX-MT $1895.00 Letter of authenticity from JSA. EX-MT $1495.00 Other Autographed Baseballs (All balls grade EX-MT/NR-MT) Authentication company shown. 1. Johnny Bench (PSA/DNA) .........................................$99.00 2. Steve Garvey (PSA/DNA) ............................................ 59.95 3. Ben Grieve (Tristar) ..................................................... 21.95 4. Ken Griffey Jr. (Pro Sportsworld) ..............................299.95 5. Bill Madlock (Tristar) .................................................... 34.95 6. Mickey Mantle (Scoreboard, Inc.) ..............................695.00 7. Don Mattingly (PSA/DNA) ...........................................99.00 8. Willie Mays (PSA/DNA) .............................................295.00 9. Pete Rose (PSA/DNA) .................................................99.00 10. Nolan Ryan (Mill Creek Sports) ............................... 199.00 Other Autographed Baseballs (Sold as-is w/no authentication) All Time MLB Records Club 3000 Strike Out Club 11. -

Torrance Press

Sunday, January 22, !9&f THE PRESS Ruth League Table Tennis Registration PRESS Scheduled Referee Blind Al Welch. President of the While students were play North Torrance Babe Ruth ing table tennis in a recrea League, announced that the tion room at Western Reserve League will hold players' re College ,in Cleveland. Ohio gistrations on Saturday, Feb in 1947, a fellow student who ruary 11, lOfil startin'g at 0 Bowling has its code of ethics and sportsmanship and j was totally blind requested a.m. at Guenser Park located Gable House hopes that each bowler, league or other, ^fol-jthat he be named referte. at 178th and Gramercy. lows the few simple and courteous rules. ' j From that moment on, In case of rain the registra winter ntr WAV i Chuck Meddick has become tions will take place on Sat RIGHT OF WAY - - /well-known for his table ten* urday February 18th at 9 a.m. The bowler on the lane to your right has the right of nig officiating, which he does Boys aged 13, 14 and 15 way. You can give him a quick sign to go ahead as not to strictly- - -by ear. Los Angeles Angels to Hold are invited to register for the slow up the game. Let each Now a newspaper writer corning ball season. They bowler take this time as bowl- for a Long Beach publication, should bring birth certificate ing should be fun and not a | Meddick is rated the No. 1 or other proof of birth date CONGRATULATING constant heckling game. -

Kit Young's Sale #131

page 1 KIT YOUNG’S SALE #131 1952-55 DORMAND POSTCARDS We are breaking a sharp set of the scarce 1950’s Dormand cards. These are gorgeous full color postcards used as premiums to honor fan autograph requests. These are 3-1/2” x 5-1/2” and feature many of the game’s greats. We have a few of the blank back versions plus other variations. Also, some have been mailed so they usually include a person’s address (or a date) plus the 2 cent stamp. These are marked with an asterisk (*). 109 Allie Reynolds .................................................................................. NR-MT 35.00; EX-MT 25.00 110 Gil McDougald (small signature) ..................................................................... autographed 50.00 110 Gil McDougald (small signature) ..............................................................................NR-MT 50.00 110 Gil McDougald (large signature) ....................................................... NR-MT 30.00; EX-MT 25.00 111 Mickey Mantle (bat on shoulder) ................................................. EX 99.00; GD watermark 49.00 111 Mickey Mantle (batting) ........................................................................................ EX-MT 199.00 111 Mickey Mantle (jumbo 6” x 9” blank back) ..................................................... EX-MT rare 495.00 111 Mickey Mantle (jumbo 6” x 9” postcard back) ................................................ GD-VG rare 229.00 111 Mickey Mantle (super jumbo 9” x 12” postcard back) .......................VG/VG-EX tape back 325.00 112