Read Our Scoping Comments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPEAL of DECISION NOTICE, GUNNISON RANGER DISTRICT Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison National Forests

APPEAL OF DECISION NOTICE, GUNNISON RANGER DISTRICT Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison National Forests DOUBLE HEART RANCH, ON BEHALF OF LOCAL LANDOWNERS AND INTERESTED CITIZENS APPELLANTS Notice of Appeal, Statement of Reasons and Request for Relief Regarding the Geothermal Lease Nomination COC- 73584 EA and DN v. CHARLES RICHMOND GMUG FOREST SUPERVISOR AND JOHN MURPHY GUNNISON RANGER DISTRICT RESPONDENTS NOTICE OF APPEAL STATEMENT OF REASONS AND RELIEF REQUESTED DATED this 25 th day of March, 2011 Matthew R. Jones Double Heart Ranch 7500 County Road 887 Gunnison, CO 81230 Direct: (512) 635-7814 Fax: (214) 378-7501 Email: [email protected] David Brown Ranch Manager: (970) 641-0690 1 NOTICE OF APPEAL On February 10, 2011, Forest Supervisor Charles Richmond signed the Decision Notice for Geothermal Lease Nomination COC-73584. This is a Notice of Appeal of that decision pursuant to 36 C.F.R. Part 215. The Double Heart Ranch, Local Landowners, and a great many others use and enjoy the Tomichi Dome, and the surrounding lands covered by this decision. Further, DH Ranch submitted comments at every stage of this process to every agency involved to be considered for this National Environmental Policy Act process. DH Ranch also attended every public meeting, even when notice was grossly insufficient and public comment was inappropriately restricted and prevented. This appeal is timely pursuant to 36 C.F.R. §215.14. Appellant requests that the DN be withdrawn, a proper NEPA process be conducted, and a new decision of No Action be issued, protecting our public resources. THE APPELLANTS The Double Heart Ranch is a historic Colorado property wholly situated on or around the Tomichi Dome and the property encompassed by this decision. -

Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison National Forests Road - Light Duty ¤£87 Q Private Intermittent Stream 550 Disclaimer ¤£ ¤£50 114 U.S

9 9 9 0 0 2 9 0 0 0 9 2 2 0 00 0 9000 0 0 0 9 9 000 0 2 9 0 200 9 0 96 0 2 0 00 0 ! 00 ! 90 8800 90 C o 94 ! 00 k 9600 a e 0 17 80 l e 8 9 ! 9 9 C 0 16 r 2 40 0 0 ! 00 00 13 0 0 9 r 940 9 C 14 200 0 18 e ! 15 ! ! s e k a k e l 7 l 00 4 e 90 17 15 0 r ! a 16 9400 0 00 14 C 17 D 6 C r 9 Propose13d Whitehouse Add1i8tions to the 20 ! h e ! k c a W t 8600 8 ! r t ! n x Willow i 7 7 o h 8 n e 2 9200 D 1 F i 0 D 9400 o t 0 0 t Swamp e n n 5 s 9 h Mt. Sneffels Wilderness, 2 00 8 ! 00 w 78 e ! D o o 7 u i W T t 2 ! 1 V c s ! 5 0 Moonshine y e 0 . a ! 0 h 6 60 2 n a 8 9 7 c C March 22, 2018 ! 0 A 0 e w 960 r Park ! g 9600 5 C e ! d 8 r Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre i e e 8 k ! e R ! 5 00 k 6 ! 9 ! 2 ! ! . Lake 9600 0 1 1 40 . and Gunnison 9 A ! Map depicts proLpenooresed boundaries for the Whitehouse ! 1 ! 21 5 ! ! 9 ! ! 8 8 0 ! 0 0 ! 22 9 B 0 6 National Forests Additions to the Mt. -

Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison National Forests

9 9 9 0 0 2 9 0 0 0 9 2 2 0 00 0 9000 0 0 0 9 9 000 0 2 9 0 200 9 0 96 0 2 18 0 0 0 0 9000 8800 8 90 C 94 0 5 o 871 00 k 1 9600 .1 a e 5 00 17 8 l e 8 8 9 9 16 9 2 C 400 r 0 13 00 00 00 20 0 9 r 940 9 C 14 200 0 0 18 e . 15 1A s e k a k e 8 l 7 40 l 00 4 e 0 90 0 r a 17 16 9400 15 0 0 14 C D 60 r 9 C Propose13d Whitehouse Additions to the 20 h 8 k W e c a t 8600 r t 5 x 87 i 7 1 Willow n o h 8 2 e 9200 D n F i 0 D 400 t . 0 Swamp 9 o e t n 2 1 s 9 n h Mt. Sneffels Wilderness, 2 800 8 00 w 0 B 7 e o o D 7 0 u W T i 2 1 V t s c 5 0 Moonshine a y 0 e 00 . h 6 6 2 n a 8 9 7 C April 8, 2016 c 9600 A e w Park r g 9600 C e d r Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre i e 0 8 0 e 8 0 1 k 5 e R 2 7 0 k 5 1 5 2 8 2 . -

36 CFR Ch. II (7–1–13 Edition) § 294.49

§ 294.49 36 CFR Ch. II (7–1–13 Edition) subpart shall prohibit a responsible of- Line Includes ficial from further restricting activi- Colorado roadless area name upper tier No. acres ties allowed within Colorado Roadless Areas. This subpart does not compel 22 North St. Vrain ............................................ X the amendment or revision of any land 23 Rawah Adjacent Areas ............................... X 24 Square Top Mountain ................................. X management plan. 25 Troublesome ............................................... X (d) The prohibitions and restrictions 26 Vasquez Adjacent Area .............................. X established in this subpart are not sub- 27 White Pine Mountain. ject to reconsideration, revision, or re- 28 Williams Fork.............................................. X scission in subsequent project decisions Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, Gunnison National Forest or land management plan amendments 29 Agate Creek. or revisions undertaken pursuant to 36 30 American Flag Mountain. CFR part 219. 31 Baldy. (e) Nothing in this subpart waives 32 Battlements. any applicable requirements regarding 33 Beaver ........................................................ X 34 Beckwiths. site specific environmental analysis, 35 Calamity Basin. public involvement, consultation with 36 Cannibal Plateau. Tribes and other agencies, or compli- 37 Canyon Creek-Antero. 38 Canyon Creek. ance with applicable laws. 39 Carson ........................................................ X (f) If any provision in this subpart -

Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests DRAFT Wilderness Evaluation Report August 2018

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests DRAFT Wilderness Evaluation Report August 2018 Designated in the original Wilderness Act of 1964, the Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness covers more than 183,000 acres spanning the Gunnison and White River National Forests. In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

Uncompahgre Wilderness Trails

TH Little Cimarron TH Big WARNING: Do not use this map for wilderness Blue navigation. It is intended for general reference 864 UNCOMPAHGRE 229 only. Detailed maps are available at the locations 863 East shown on the back panel. Fork 867 TH Fall WILDERNESS 858 861 TH Creek 868 149 Little Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, 232 Elk Fall Creek TH 868 Little Cimarron River & Gunnison National Forests East Fork Cimarron River A 254 231 Straley 03/14/11 12 219 Middle Fork Cimarron River West Fork Cimarron River Owl Creek 233 Pass Sheep Mountain 253 Stealey 219 228 Mountain Big Blue Creek Middle TH Fork 244 860 218 Slide Courthouse Pinnacle 229 Lake Mountain 218 Ridge Dunsinane Elk Creek 144 Mountain 218 857 Precipice 211 Peak 243 Dixie 550 258 Ridge Porphory 227 Basin Silver Jack 232 Mine Ruins 235 212 Silver Mountain 216 216 234 TH Independence 138 226 231 228 233 137 Cutler Redcliff 244 Peak TH 236 235 216 Coxcomb Peak 227 232 872 220 236.3A 217 132 142 Uncompahgre Peak Larson 14,309 Ft Lakes Matterhorn 135 228 239 Lake Fork Gunnison River Peak 871 Cow Creek Uncompahgre 236 B Wetterhorn Wetterhorn 239 TH 149 Peak Basin Peak 233 14 14,015 Ft 205 233 233 226 Crystal Peak 256 235 136 Crystal Uncompahgre River 214 Bighorn Larson 241 Ridge 245 Crystal Broken 238 TH North Hill Lake Bridge of 236 215 Heaven 877 226 TH Matterhorn USFS 140 Lake City 1 Mile Blackwall BLM Mountain Ouray 870 215 20 Alpine Loop USFS Capitol City Scenic Byway Primary Highway Summit Over 13,000 Feet Wildhorse BLM (Site) Peak Improved Road Stock May Be Restricted Hensen Creek A1 Dallas A2 Courthouse Mountain A3 Sheep Mountain Primitive Road TH Trailhead TH Bear 241 A4 Alpine Plateau Creek B1 Ouray National Forest Trail 235 National Forest Trail Sunshine B2 Wetterhorn Peak American Darley Varden Flats Mountain B3 Uncompahgre Peak NOTICE: Sheep grazing is permitted in the Uncompahgre Wilderness, Mountain B4 Lake City and livestock protection dogs may be encountered near bands of Forest Boundary 118 National Forest Road sheep. -

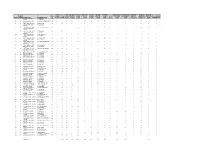

Region Forest Number Forest Name Wilderness Name Wild

WILD FIRE INVASIVE AIR QUALITY EDUCATION OPP FOR REC SITE OUTFITTER ADEQUATE PLAN INFORMATION IM UPWARD IM NEEDS BASELINE FOREST WILD MANAGED TOTAL PLANS PLANTS VALUES PLANS SOLITUDE INVENTORY GUIDE NO OG STANDARDS MANAGEMENT REP DATA ASSESSMNT WORKFORCE IM VOLUNTEERS REGION NUMBER FOREST NAME WILDERNESS NAME ID TO STD? SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE FLAG SCORE SCORE COMPL FLAG COMPL FLAG SCORE USED EFF FLAG 02 02 BIGHORN NATIONAL CLOUD PEAK 080 Y 76 8 10 10 6 4 8 10 N 8 8 Y N 4 N FOREST WILDERNESS 02 03 BLACK HILLS NATIONAL BLACK ELK WILDERNESS 172 Y 84 10 10 4 10 10 10 10 N 8 8 Y N 4 N FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP FOSSIL RIDGE 416 N 59 6 5 2 6 8 8 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP LA GARITA WILDERNESS 032 Y 61 6 3 10 4 6 8 8 N 6 6 Y N 4 Y GUNNISON NATIONAL FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP LIZARD HEAD 040 N 47 6 3 2 4 6 4 6 N 6 8 Y N 2 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP MOUNT SNEFFELS 167 N 45 6 5 2 2 6 4 8 N 4 6 Y N 2 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP POWDERHORN 413 Y 62 6 6 2 6 8 10 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP RAGGEDS WILDERNESS 170 Y 62 0 6 10 6 6 10 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP UNCOMPAHGRE 037 N 45 6 5 2 2 6 4 8 N 4 6 Y N 2 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP WEST ELK WILDERNESS 039 N 56 0 6 10 6 6 4 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL FOREST 02 06 MEDICINE BOW-ROUTT ENCAMPMENT RIVER 327 N 54 10 6 2 6 6 8 6 -

113Th CONGRESS 1St Session S. 341 in the SENATE of the UNITED

S 341 IS 113th CONGRESS 1st Session S. 341 To designate certain lands in San Miguel, Ouray, and San Juan Counties, Colorado, as wilderness, and for other purposes. IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES February 14, 2013 Mr. UDALL of Colorado (for himself and Mr. BENNET) introduced the following bill; which was read twice and referred to the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources A BILL To designate certain lands in San Miguel, Ouray, and San Juan Counties, Colorado, as wilderness, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. This Act may be cited as the `San Juan Mountains Wilderness Act'. SEC. 2. DEFINITIONS. In this Act: (1) COVERED LAND- The term `covered land' means-- (A) land designated as wilderness under paragraphs (20) through (22) of section 2(a) of the Colorado Wilderness Act of 1993 (16 U.S.C. 1132 note; Public Law 103-77; 107 Stat. 756); and (B) land in the Special Management Area. (2) SECRETARY- The term `Secretary' means the Secretary of Agriculture. (3) SPECIAL MANAGEMENT AREA- The term `Special Management Area' means the Sheep Mountain Special Management Area designated by section 4(a). (4) STATE- The term `State' means the State of Colorado. SEC. 3. ADDITIONS TO THE NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM. Section 2(a) of the Colorado Wilderness Act of 1993 (16 U.S.C. 1132 note; Public Law 103-77; 107 Stat. 756) is amended by adding at the end the following: `(20) LIZARD HEAD WILDERNESS ADDITION- Certain Federal land in the Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests comprising approximately 3,350 acres, as generally depicted on the map entitled `Proposed Wilson, Sunshine, Black Face and San Bernardo Additions to the Lizard Head Wilderness' and dated December 1, 2010, which is incorporated in, and shall be administered as part of, the Lizard Head Wilderness. -

SHORT HIKES Lakes Hiking Trails Map Have a Turbulent History

Theh lakesl k ffeaturedd on theh enclosedl d Wardd SHORT HIKES Lakes hiking trails map have a turbulent history. Several short hikes will take you by the sites of the following story. L21 ON GRAND MESA Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre PHOTO: GRAND MESA BYWAY ASSOCIATION and Old time residents felt very strongly about Gunnison National Forests their right to fish, or maybe it was their disregard for other people’s rights to own WILLIAM RADCLIFFE AS HE APPEARED a lake. Whatever the case, the Grand IN THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN NEWS IN JULY, 1901 Mesa Feud was a long-term battle PHOTO: DENVER PUBLIC LIBRARY, WESTERN HISTORY DEPARTMENT between fish poachers and private property Thehd Grand Mesa retains its nice flat f tabletop thanks to a cap of owners. While most settlers homesteaded in the valley in order basalt it acquired over nine million years ago. As the basalt lava VISITOR CENTER VIEW FROM LOWER PARKING LOT to raise and harvest crops, a few men homesteaded on top of flowed from fissures (cracks in the earth), it filled a wide flat PHOTO: GRAND MESA BYWAY ASSOCIATION Grand Mesa in order to harvest fish. Locals were not under- valley. Eventually, the soft rock around the basalt valley eroded The National Forest Visitor Center is the perfect place to learn standing of this idea, so they continued to fish. away leaving a mesa high in the air. Later (14,000 years ago), ice more about the Grand Mesa. Staff is available to answer caps rearranged rocky debris into troughs that caught melting questions on recreation opportunities, natural resources and the The feud heated up in 1896 snow to form more than 300 lakes and reservoirs on top of the area. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 10/01/2016 to 12/31/2016 Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison National Forests This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring in more than one Region (excluding Nationwide) Western Area Power - Special use management On Hold N/A N/A David Loomis Administration Right-of-Way 303-275-5008 Maintenance and [email protected] Reauthorization Project Description: Update vegetation management activities along 278 miles of transmission lines located on NFS lands in Colorado, EIS Nebraska, and Utah. These activities are intended to protect the transmission lines by managing for stable, low growth vegetation. Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/nepa/nepa_project_exp.php?project=30630 Location: UNIT - Ashley National Forest All Units, Grand Valley Ranger District, Norwood Ranger District, Yampa Ranger District, Hahns Peak/Bears Ears Ranger District, Pine Ridge Ranger District, Sulphur Ranger District, East Zone/Dillon Ranger District, Paonia Ranger District, Boulder Ranger District, West Zone/Sopris Ranger District, Canyon Lakes Ranger District, Salida Ranger District, Gunnison Ranger District, Mancos/Dolores Ranger District. STATE - Colorado, Nebraska, Utah. COUNTY - Chaffee, Delta, Dolores, Eagle, Grand, Gunnison, Jackson, Lake, La Plata, Larimer, Mesa, Montrose, Routt, Saguache, San Juan, Dawes, Daggett, Uintah. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Linear transmission lines located in Colorado, Utah, and Nebraska. R2 - Rocky Mountain Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Aspen-Sopris Ranger District - Special use management Completed Actual: 06/13/2016 06/2016 Hillary Santana Five Year Recreation Event 970-945-3202 Special Use Permit Issuance [email protected] CE Description: Issuance of five year recreation event permits to authorize 11 recreation events to operate on the Aspen-Sopris *UPDATED* Ranger District. -

Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison National Forests ¤£ Q !

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 0 k ! 100 60 ! ! 0 ! 0 1 9 0 $ ! 0 0 ! e ! 6 200 11 1 00 1 1 6 9 1200 98 0200 1 ! 0 ! 1 ! 0 e 8 0 1 6 ! 6 r 0 ! 0 0 0 0 0 ! 0 0 600 ! 0 ! ! 0 18 0 0 ! 1 0 C ! 1 4 0 Hayden T.44N., 9 98 1 9 0 ! ! ! 0 10400 ! A s 0400 0 $ l 0800 a 860 d 1 l 0 R.9W., 23 l ! ! e 1140 ! Peak ! 0800 B ! 1 r a 000 0 ! 0 0 1060 ! e C 0 D 1 0 6 0 ! 88 8 ! 0 1 a 0 0 ! r 1 1 k Proposed Liberty Bell and Last Dollar e ! v r 00 00 10 0 ! 8 ! e 11 e 0 k o ! 08 0 ! r 1 $ ! $ F 00 $ 2200 ! 06 C $ T.44N., ! 1 1 $ t ! $ r s ! 2 12800 ! Additions to the Mt. Sneffels Wildernese s, ! e 1 ! 0 R.10W., 23 e 0 0 ! 110 80 ! 20 0 0 k 0 W 80 1 ! ! 21 $ 1 0 ! $ 12600 ! 0 $ 3 6 $ ! 1 ! 0 9 0 $ 0000 0 00 Liberty ! Bell East Special Management Area 1120 ! 6 $ 12400 0 11 ! k ! 1 ! e ! 1400 ! 12200 ! e ! r ! 1160 ! 0 ! ! ! 18 1 00 ! C 2 00 118 ! 00 ! March 8, 2018 12000 s ! ! T.44N., 9400 a l ! 00 ! 0 l 110 12 a 00 ! !! R.8W., 23 D ! 0 ! ! ! Whitehouse ! 1 ! k ! ! 5 ! ! $ r $ ! ! Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre 10800 o 400 ! ! 10 $ ! 112 ! ! ! F Ma00 p depicts proposed boundaries for the Liberty Bell and $ ! ! ! ! Wilderness $ ! t 3 ! ! $ ! ! ! s 0 ! ! ! ! a 11400 2! ! ! ! ! ! ! E Last Dollar Additions to the Mt. -

THE GUNNISON RIVER BASIN a HANDBOOK for INHABITANTS from the Gunnison Basin Roundtable 2013-14

THE GUNNISON RIVER BASIN A HANDBOOK FOR INHABITANTS from the Gunnison Basin Roundtable 2013-14 hen someone says ‘water problems,’ do you tend to say, ‘Oh, that’s too complicated; I’ll leave that to the experts’? Members of the Gunnison Basin WRoundtable - citizens like you - say you can no longer afford that excuse. Colorado is launching into a multi-generational water planning process; this is a challenge with many technical aspects, but the heart of it is a ‘problem in democracy’: given the primacy of water to all life, will we help shape our own future? Those of us who love our Gunnison River Basin - the river that runs through us all - need to give this our attention. Please read on.... Photo by Luke Reschke 1 -- George Sibley, Handbook Editor People are going to continue to move to Colorado - demographers project between 3 and 5 million new people by 2050, a 60 to 100 percent increase over today’s population. They will all need water, in a state whose water resources are already stressed. So the governor this year has asked for a State Water Plan. Virtually all of the new people will move into existing urban and suburban Projected Growth areas and adjacent new developments - by River Basins and four-fifths of them are expected to <DPSDYampa-White %DVLQ Basin move to the “Front Range” metropolis Southwest Basin now stretching almost unbroken from 6RXWKZHVW %DVLQ South Platte Basin Fort Collins through the Denver region 6RXWK 3ODWWH %DVLQ Rio Grande Basin to Pueblo, along the base of the moun- 5LR *UDQGH %DVLQ tains.