The Nude Beach As a Liminal Homoerotic Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexual Citizenship in Provincetown Sandra Faiman-Silva Bridgewater State College, [email protected]

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Anthropology Faculty Publications Anthropology Department 2007 The Queer Tourist in 'Straight'(?) Space: Sexual Citizenship in Provincetown Sandra Faiman-Silva Bridgewater State College, [email protected] Virtual Commons Citation Faiman-Silva, Sandra (2007). The Queer Tourist in 'Straight'(?) Space: Sexual Citizenship in Provincetown. In Anthropology Faculty Publications. Paper 14. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/anthro_fac/14 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. The Queer Tourist in ‘Straight’(?) Space: Sexual Citizenship in Provincetown Sandra Faiman-Silva, Bridgewater State College, MA, USA Abstract: Provincetown, Massachusetts USA, a rural out-of-the-way coastal village at the tip of Cape Cod with a year- round population of approximately 3,500, has ‘taken off’ since the late 1980s as a popular GLBTQ tourist destination. Long tolerant of sexual minorities, Provincetown transitioned from a Portuguese-dominated fishing village to a popular ‘queer’ gay resort mecca, as the fishing industry deteriorated drastically over the twentieth century. Today Provincetowners rely mainly on tourists—both straight and gay—who enjoy the seaside charm, rustic ambience, and a healthy dose of non-heter- normative performance content, in this richly diverse tourist milieu. As Provincetown’s popularity as a GLBTQ tourist destination increased throughout the 1980s and ‘90s, new forms of “sexual outlaw” lifestyles, including the leather crowd and the gay men’s “tourist circuit,” have appeared in Provincetown, which challenge heteronormative standards, social propriety rules, and/or simply standards of “good taste,” giving rise to moral outrage and even at time an apparent homo- phobic backlash. -

Tourism and Cultural Identity: the Case of the Polynesian Cultural Center

Athens Journal of Tourism - Volume 1, Issue 2 – Pages 101-120 Tourism and Cultural Identity: The Case of the Polynesian Cultural Center By Jeffery M. Caneen Since Boorstein (1964) the relationship between tourism and culture has been discussed primarily in terms of authenticity. This paper reviews the debate and contrasts it with the anthropological focus on cultural invention and identity. A model is presented to illustrate the relationship between the image of authenticity perceived by tourists and the cultural identity felt by indigenous hosts. A case study of the Polynesian Cultural Center in Laie, Hawaii, USA exemplifies the model’s application. This paper concludes that authenticity is too vague and contentious a concept to usefully guide indigenous people, tourism planners and practitioners in their efforts to protect culture while seeking to gain the economic benefits of tourism. It recommends, rather that preservation and enhancement of identity should be their focus. Keywords: culture, authenticity, identity, Pacific, tourism Introduction The aim of this paper is to propose a new conceptual framework for both understanding and managing the impact of tourism on indigenous host culture. In seminal works on tourism and culture the relationship between the two has been discussed primarily in terms of authenticity. But as Prideaux, et. al. have noted: “authenticity is an elusive concept that lacks a set of central identifying criteria, lacks a standard definition, varies in meaning from place to place, and has varying levels of acceptance by groups within society” (2008, p. 6). While debating the metaphysics of authenticity may have merit, it does little to guide indigenous people, tourism planners and practitioners in their efforts to protect culture while seeking to gain the economic benefits of tourism. -

Health & Wellness Tourism

A ROUTLEDGE FREEBOOK HEALTH & WELLNESS TOURISM A FOCUS ON THE GLOBAL SPA EXPERIENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS 004 :: FOREWORD 007 :: SECTION I: INTRODUCTION 008 :: 1. SPA AND WELLNESS TOURISM AND POSITIVE PSYCHOLOGY 030 :: 2. HEALTH, SOCIABILITY, POLITICS AND CULTURE: SPAS IN HISTORY, SPAS AND HISTORY 041 :: 3. A GEOGRAPHICAL AND REGIONAL ANALYSIS 059 :: SECTION II: CASE STUDIES 060 :: 4. TOWN OR COUNTRY? BRITISH SPAS AND THE URBAN/RURAL INTERFACE 076 :: 5. SARATOGA SPRINGS: FROM GENTEEL SPA TO DISNEYFIED FAMILY RESORT 087 :: 6. FROM THE MAJESTIC TO THE MUNDANE: DEMOCRACY, SOPHISTICATION AND HISTORY AMONG THE MINERAL SPAS OF AUSTRALIA 111 :: 7. HEALTH SPA TOURISM IN THE CZECH AND SLOVAK REPUBLIC 128 :: 8. TOURISM, WELLNESS, AND FEELING GOOD: REVIEWING AND STUDYING ASIAN SPA EXPERIENCES 147 :: 9. FANTASY, AUTHENTICITY, AND THE SPA TOURISM EXPERIENCE 165 :: SECTION III: CONCLUSION 166 :: 10. JOINING TOGETHER AND SHAPING THE FUTURE OF THE GLOBAL SPA AND WELLNESS INDUSTRY RELAX MORE DEEPLY WITH THE FULL TEXT OF THESE TITLES USE DISCOUNT CODE SPA20 TO GET 20% OFF THESE ROUTLEDGE TOURISM TITLES ROUTLEDGE TOURISM Visit Routledge Tourism to browse our full collection of resources on tourism, hospitality, and events. >> CLICK HERE FOREWORD HOW TO USE THIS BOOK As more serious study is devoted to different aspects of the global spa industry, it’s becoming clear that the spa is much more than a pleasant, temporary escape from our workaday lives. Indeed, the spa is a rich repository of historical, cultural, and behavioral information that is at once unique to its specific location and shared by other spas around the world. We created Health and Wellness Tourism: A Focus on the Global Spa Industry to delve further into the definition of what constitutes a spa, and showcase different perspectives on the history and evolution of spa tourism. -

The Reflexivity of Self-Identity Through Tourism

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2010 Who Am I?: The Reflexivity of Self-Identity Through Tourism Matthew Lee Milde San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Milde, Matthew Lee, "Who Am I?: The Reflexivity of Self-Identity Through Tourism" (2010). Master's Theses. 3778. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.wxw7-4t7w https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3778 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHO AM I?: THE REFLEXIVITY OF SELF-IDENTITY THROUGH TOURISM A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Hospitality, Recreation and Tourism Management San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Matthew L. Milde May 2010 © 2010 Matthew L. Milde ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled WHO AM I?: THE REFLEXIVITY OF SELF-IDENTITY THROUGH TOURISM By Matthew L. Milde APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HOSPITALITY, RECREATION AND TOURISM MANAGEMENT SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY May 2010 Dr. Ranjan Bandyopadhyay Hospitality, Recreation and Tourism Management Dr. Tsu-Hong Yen Hospitality, Recreation and Tourism Management Dr. Kim Uhlik Hospitality, Recreation and Tourism Management ABSTRACT WHO AM I?: THE REFLEXIVITY OF SELF-IDENTITY THROUGH TOURISM by Matthew L. Milde This study has set forth to close gaps, explore innovative methods, and create a better understanding of “Who am I?”, in tourism research. -

Tourism and Place in Treasure Beach, Jamaica: Imagining Paradise and the Alternative. Michael J

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1999 Tourism and Place in Treasure Beach, Jamaica: Imagining Paradise and the Alternative. Michael J. Hawkins Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Hawkins, Michael J., "Tourism and Place in Treasure Beach, Jamaica: Imagining Paradise and the Alternative." (1999). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7044. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7044 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bteedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

The Impact of Twilight Tourism on Economic Stability and Identity Development in Forks, Washington the Colorado College Hannah Tilden April 21, 2015

The Impact of Twilight Tourism on Economic Stability and Identity Development in Forks, Washington The Colorado College Hannah Tilden April 21, 2015 2 Introduction This research addresses how the introduction and consequential decrease in the popularity of the film and book series, the Twilight saga has impacted the cultural identity and economic security of residents living in Forks, Washington. The Twilight saga is a series of popular young adult novels first published in 2005, which were then adapted to film, about vampires and werewolves (Meyer 2005). This research will be framed within larger conversations of tourism, pop culture, and representation, and will take an ethnographic approach to creating a multi-vocal representation of Forks. In doing so, it contests, at least in part, the existing single narrative of the town created by author Stephenie Meyer. The ethnographic approach will include participant observation and interviews, as well as collecting economic data on the town to inform an understanding of economic security over the last decade. The research will contribute to the anthropological discourse on tourism, cultural representation, and cultural identity, and will give the people of Forks the opportunity to create their own representation of their community. Before the Twilight saga made Forks an international tourist destination after the publication of the first novel, Forks attracted local visitors for its proximity to the Hoh, the only rainforest in the continental U.S., which is surrounded by the Olympic National Park, and the Pacific Ocean (Forks Chamber of Commerce 2014). The economy is historically based on the logging and fishing industries, and the year round population is under 4,000 (Forks Chamber of Commerce 2014). -

Hiding Behind Nakedness on the Nude Beach Lelia Rosalind Green Edith Cowan University

Edith Cowan University Research Online ECU Publications Pre. 2011 2001 Hiding Behind Nakedness on the Nude Beach Lelia Rosalind Green Edith Cowan University This article was originally published as: Green, L. R. (2001). Hiding behind nakedness on the nude beach. Australian Journal of Communication, 28(3), 1-10. Original article available here. This Journal Article is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks/4455 Hiding behind nakedness on the nude beach 200201238 Lelia Green ABSTRACT This paper draws upon 0 series of experiences between 1980--85, when Iidentified as a natur ist during my summer holidays in Europe, and in a visit to Wreck 8eoch in Vancouver (where I felt very much at home). At the time, I was aware that nude beaches were much less threat ening to me as 0 large woman than are conventional 'textile' beaches. This paper drows upon those experiences to theorise why this might be the cose, and why I have been absent from beach culture for much of the past decade. INTRODUCTION t is only as I begin to work on this paper, to tease out my ideas and understandings of the years J Ispent as a nudist, that I begin to understand the lelia Green, School of margins of the circumstances in which I placed Communications and Multimedia, Edith Cowon myself. Iexperienced my nudist activity at the time University, Perth, Aus· as uncomplicated, natural, and pleasurable-if tralia. An earlier version of somewhat hidden. It is only as I come to theorise this paper WQS presented these choices that Isee that they are inscribed with at On the Beach: Cultural all kinds of different taboos, invisible to me then. -

Branding the Costa Rican Nation Ecotourism and National Identity As

Branding the Costa Rican Nation Ecotourism and National Identity as Nation Branding Strategies Gaby Sebel S1652729 Master Thesis Latin American Studies Public Policies Leiden University Prof. dr. Silva Leiden, 9 July 2020 Table of Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………...iii Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter 1: Nation Branding, National Identity, and Ecotourism: A Theoretical Framework...4 1.1 Nation Branding and Its Strategies: Country Image and Tourism………………...4 1.2 National Identity: What Is It and What Is It Not?…………………………………8 1.3 Ecotourism as Destination Brand………………………………………………...12 Chapter 2: Nation-Building, National Identity, and Nation Branding in Costa Rica………...17 2.1 The Independence and Nation-Building of Costa Rica…………………………..17 2.2 Costa Rica’s Unique National Identity…………………………………………...20 2.3 The Development of Ecotourism in Costa Rica………………………………….22 2.4 How the Costa Rican Institute of Tourism Nation Brands Costa Rica…………..25 Chapter 3: Selling the Costa Rican Nation…………………………………………………...29 3.1 Costa Rica’s Tourism Brand to Nation Brand…………………………………...29 3.2 The Role of Esencial Costa Rica in Costa Rica’s Nation Branding……………...32 3.3 National Identity as Costa Rica’s Nation Branding Strategy…………………….35 3.4 Ecotourism as Costa Rica’s Nation Branding Strategy…………………………..37 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………42 References……………………………………………………………………………………45 Appendices…………………………………………………………………………………...50 Appendix 1: Promotion of Esencial Costa Rica Abroad……………………………..50 Appendix 2: Survey for International Tourists………………………………………51 Appendix 3: Surveys for Ticos……………………………………………………….53 ii Acknowledgements With this thesis, I finalise the Master Latin American Studies at the Leiden University. It has been a very challenging, accomplished, and highly rewarding year. Especially the research period in Costa Rica has been valuable in terms of research and experience. -

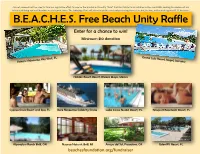

B.E.A.C.H.E.S. Free Beach Unity Raffle Enter for a Chance to Win! Minimum $10 Donation

ALL net proceeds will be used to fund our legislative effort to reverse the blanket anti-nudity "Rule" that DEP/State Parks installed in the mid-1980s causing the closure of our historic clothing-optional beaches on state park lands. The lobbying effort will clear the path to not only restoring these sites but, in time, add new designated C.O. beaches. B.E.A.C.H.E.S. Free Beach Unity Raffle Enter for a chance to win! Minimum $10 donation Hidden Beach Resort, Riviera Maya, Mexico Cypress Cove Resort and Spa, FL Bare Necessities Celebrity Cruise Lake Como Nudist Resort, FL Newport Beachside Resort, FL Alpenglow Ranch BnB, OR Nuance Naturist BnB, MI Arroyo del Sol, Pasadena, CA Eden RV Resort, FL beachesfoundation.org/fundraiser B.E.A.C.H.E.S. Free Beach Unity Raffle 1st PRIZE: Helen’s Hideaway, Key West, FL 5d/4n. Value: $3,150 Search: Helen’s Hideaway, FL 2nd PRIZE: Grand Lido Resort w/ airfare from Fox Travel. Negril, Jamaica. 4d/3n. Value: $3100 grandlidoresorts.com 3rd PRIZE: Hidden Beach Resort Au Naturel. Riviera Maya, Mexico. 4d/3n. Value: $1950 karismahotels.com/hidden-beach 4th PRIZE: Cypress Cove Nudist Resort/Spa, Kissimmee, FL. 7d/6n. Value: $900 CypressCoveResort.com 5th PRIZE: 2021 Bare Necessities Cruise, cabin discounts on Carnival Legend and swag bags. Departing Tampa, FL 13d/12n. Value: $400-$800 CruiseBare.com The drawing will be held on Saturday, March 28, 2020 at 2 pm at Haulover Beach. 6th PRIZE: Lake Como Family Nudist Resort, Lutz, FL 7d/6n. Value: $600 LakeComoNaturally.com Winners need not be present to win. -

Spain Voted Number One for Nude Beaches France First for Bare Resorts

Nude beach opinion poll Press release 27 June 2008 Executive summary UK naturists say: • Spain is number one for nude beaches • The best naturist resorts are in France • The best beach for first-time nudists is Vera Playa in Spain; in the UK it's Studland Bay • Europe's best nude beach is at the French naturist resort of Cap d'Agde • Top islands for bare bathing are Fuerteventura (Canaries) and Formentera (Balearices) Issued by Lifestyle Press Ltd, publisher of 'The World's Best Nude Beaches and Resorts' Spain voted number one for nude beaches Spain and the Spanish islands have Europe's best nude beaches, according to a survey of Britain's naturist Q1. Which European country has the best holiday-makers. Baring all on the costas won 36% of bare nude beaches? Britons' votes, compared to 34% who named France as their favourite for all-over bathing. In third place were 1. Spain and islands 36.0% Greece and the Greek islands, with 10%. 2. France 34.4% 3. Greece and islands 10.4% These findings were revealed by publishers of 'The World's 4. Croatia 7.8% Best Nude Beaches and Resorts', from a survey of more 5. UK 3.0% than 500 UK naturists. "We think this is the largest detailed poll on holiday nudity by the experts and it's amazing to see Spain coming top. Thirty years ago nude bathing was illegal there and now the country and islands have several hundred beaches used by unclad holiday makers. France is well-known for its nude beaches, but we were slightly surprised that Greece came third – other countries such as Croatia have done far more to promote their holidays in the altogether," said Nick Mayhew, author of the guide. -

A LOCAL PERSPECTIVE on ECOTOURISM in CRETE Ioannis

JOURNAL ON TOURISM & SUSTAINABILITY Volume 2 Issue 1 November 2018 ISSN: 2515-6780 ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ A LOCAL PERSPECTIVE ON ECOTOURISM IN CRETE Ioannis Saatsakis*, Ali Bakir** & Eugenia Wickens * Atlas Travel Services, Crete, **Bucks New University, England, UK Abstract: Drawing upon the findings of an empirical study of ecotourism in Crete (Saatsakis, 2018), this industry focussed paper discusses and reflects upon the development of successful ecotourism for the Island and its well-being. Greece, including the island of Crete, is strongly committed to the implementation of the 2030 agenda for the sustainable development in balancing its economic growth, protection of the environment and social cohesion, so “no one is left behind”. The paper is supported with evidence from research of several years in Crete and from personal experience of the first author working in the Cretan tourism industry, both in the public and private sectors (Saatsakis, 2018). Keywords: Ecotourism, Crete, Sustainability, Development, Challenges, Tourism planning Introduction The paper is based on the researchers’ experience and expertise on tourism sustainable development and policy. The Cretan ecotourism policy is influenced by values which reflect the protection of the scenic beauty of the island of Crete, its traditional way of life and culture. The policy aims to alleviate the detrimental impacts of mass tourism by diversifying and introducing alternative types of tourism. This paper highlights the measures that are needed to be taken by all stakeholders involved in the tourism industry as articulated by prominent writers in the field (e.g., Buckley, 2009, 2012; Fennell, 2014; Hunter, 2007; Mason, 2015; Wearing & Neil, 2009) and recommended by the UN Sustainable Development Goals for 2030. -

1974-Venice Beach

APPENDIX A Venice. The police were informed that, in the absence of specific anti-nudity legislation, BFUSA would challenge any arrests in court. That first weekend was a smashing success with perhaps a hundred nudists enjoying their new beach. Even a Los Angeles Times editorial supported the idea of sharing the beach. However, word spread rapidly and within a few weeks, the nudists were vastly outnumbered by gawkers and the media. Property was trampled, and traffic slowed to a stop. The nudists appealed to the LA City Council to pass 1976 NATIONAL NUDE DAY MARCH TO VENICE BEACH a law legalizing the beach, and the proposal received a favorable 90-minute hearing followed by a 10-3 1974: HOW VENICE positive vote. The nudist community was overjoyed. BEACH ALMOST But since the vote was not unanimous, the item had to come back to the council for a second reading and BECAME LEGALLY vote two weeks later. NUDE During those two weeks, those opposed to the beach By Gary Mussell, launched a suffocating campaign aimed at reversing the decision. Archbishop Roger Mahoney (not May 4, 2015 yet a Cardinal) urged all Catholics in the city to As the 1970s dawned, the Counterculture Age began oppose the nude beach and to write letters to their to discover the joy of sunbathing nude. Beach nudists city council members. Law enforcement officials got their first big break in June, 1972, when the and other local “experts” were interviewed on news California Supreme Court unanimously decided in programs warning of increased crime and vandalism the Chad Merrill Smith case that mere nudity if the nude beach was approved.