Music Written for Bassoon by Bassoonists: an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saturday Playlist

October 26, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “To achieve great things, two things are needed: a plan, and not quite enough time.” — Leonard Bernstein Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Awake! 00:01 Buy Now! Haydn Symphony No. 008 in G, "Evening" English Concert/Pinnock Archiv 423 098 028942309821 00:24 Buy Now! Scarlatti, D. Sonata in A, Kirkpatrick 212 Murray Perahia Sony 63380 07464633802 00:28 Buy Now! Grieg Symphonic Dances, Op. 64 Philharmonia Orchestra/Leppard Philips 438 380 02894388023 Academy of St. Martin-in-the- 01:00 Buy Now! Rossini Overture ~ Cinderella EMI 49155 077774915526 Fields/Marriner 01:09 Buy Now! Parry Elegy for Brahms London Philharmonic/Boult EMI 49022 07777490222 01:20 Buy Now! Brahms Sextet No. 1 in B flat, Op. 18 Stern/Lin/Laredo/Tree/Ma/Robinson Sony Classical 45820 07464458202 02:00 Buy Now! Mozart Fantasia in C minor, K. 475 Alicia de Larrocha RCA Red Seal 60453 090266045327 Lento assai ~ String Quartet in F, Op. 135 (arr. 02:15 Buy Now! Beethoven Royal Philharmonic/Rosekrans Telarc 80562 089408056222 for string orchestra) 02:27 Buy Now! Gade Symphony No. 7 in F, Op. 45 Stockholm Sinfonietta/Jarvi BIS 355 7318590003558 03:00 Buy Now! Debussy Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun Zoeller/Berlin Philharmonic/Karajan EMI 65914 724356591424 03:11 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Cello Sonata No. 1 in B flat, Op. 45 Rosen/Artymiw Bridge 9501 090404950124 03:37 Buy Now! Offenbach Offenbachiana Monte Carlo Philharmonic/Rosenthal Naxos 8.554005 N/A 04:01 Buy Now! Saint-Saëns Havanaise, Op. -

On the Question of the Baroque Instrumental Concerto Typology

Musica Iagellonica 2012 ISSN 1233-9679 Piotr WILK (Kraków) On the question of the Baroque instrumental concerto typology A concerto was one of the most important genres of instrumental music in the Baroque period. The composers who contributed to the development of this musical genre have significantly influenced the shape of the orchestral tex- ture and created a model of the relationship between a soloist and an orchestra, which is still in use today. In terms of its form and style, the Baroque concerto is much more varied than a concerto in any other period in the music history. This diversity and ingenious approaches are causing many challenges that the researches of the genre are bound to face. In this article, I will attempt to re- view existing classifications of the Baroque concerto, and introduce my own typology, which I believe, will facilitate more accurate and clearer description of the content of historical sources. When thinking of the Baroque concerto today, usually three types of genre come to mind: solo concerto, concerto grosso and orchestral concerto. Such classification was first introduced by Manfred Bukofzer in his definitive monograph Music in the Baroque Era. 1 While agreeing with Arnold Schering’s pioneering typology where the author identifies solo concerto, concerto grosso and sinfonia-concerto in the Baroque, Bukofzer notes that the last term is mis- 1 M. Bukofzer, Music in the Baroque Era. From Monteverdi to Bach, New York 1947: 318– –319. 83 Piotr Wilk leading, and that for works where a soloist is not called for, the term ‘orchestral concerto’ should rather be used. -

Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: a Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras

Texas Music Education Research, 2012 V. D. Baker Edited by Mary Ellen Cavitt, Texas State University—San Marcos Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: A Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras Vicki D. Baker Texas Woman’s University The violin, viola, cello, and double bass have fluctuated in both their gender acceptability and association through the centuries. This can partially be attributed to the historical background of women’s involvement in music. Both church and society rigidly enforced rules regarding women’s participation in instrumental music performance during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. In the 1700s, Antonio Vivaldi established an all-female string orchestra and composed music for their performance. In the early 1800s, women were not allowed to perform in public and were severely limited in their musical training. Towards the end of the 19th century, it became more acceptable for women to study violin and cello, but they were forbidden to play in professional orchestras. Societal beliefs and conventions regarding the female body and allure were an additional obstacle to women as orchestral musicians, due to trepidation about their physiological strength and the view that some instruments were “unsightly for women to play, either because their presence interferes with men’s enjoyment of the female face or body, or because a playing position is judged to be indecorous” (Doubleday, 2008, p. 18). In Victorian England, female cellists were required to play in problematic “side-saddle” positions to prevent placing their instrument between opened legs (Cowling, 1983). The piano, harp, and guitar were deemed to be the only suitable feminine instruments in North America during the 19th Century in that they could be used to accompany ones singing and “required no facial exertions or body movements that interfered with the portrait of grace the lady musician was to emanate” (Tick, 1987, p. -

Working List of Repertoire for Tenor Trombone Solo and Bass Trombone Solo by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) and Women Composers

Working List of Repertoire for tenor trombone solo and bass trombone solo by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) and Women Composers Working list v.2.4 ~ May 30, 2021 Prepared by Douglas Yeo, Guest Lecturer of Trombone Wheaton College Conservatory of Music Armerding Center for Music and the Arts www.wheaton.edu/conservatory 520 E. Kenilworth Avenue Wheaton, IL 60187 Email: [email protected] www.wheaton.edu/academics/faculty/douglas-yeo Works by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) Composers: Tenor trombone • Amis, Kenneth Preludes 1–5 (with piano) www.kennethamis.com • Barfield, Anthony Meditations of Sound and Light (with piano) Red Sky (with piano/band) Soliloquy (with trombone quartet) www.anthonybarfield.com 1 • Baker, David Concert Piece (with string orchestra) - Lauren Keiser Publishing • Chavez, Carlos Concerto (with orchestra) - G. Schirmer • Coleridge-Taylor, Samuel (arr. Ralph Sauer) Gypsy Song & Dance (with piano) www.cherryclassics.com • DaCosta, Noel Four Preludes (with piano) Street Calls (unaccompanied) • Davis, Nathaniel Cleophas (arr. Aaron Hettinga) Oh Slip It Man (with piano) Mr. Trombonology (with piano) Miss Trombonism (with piano) Master Trombone (with piano) Trombone Francais (with piano) www.cherryclassics.com • John Duncan Concerto (with orchestra) Divertimento (with string quartet) Three Proclamations (with string quartet) library.umkc.edu/archival-collections/duncan • Hailstork, Adolphus Cunningham John Henry’s Big (Man vs. Machine) (with piano) - Theodore Presser • Hong, Sungji Feromenis pnois (unaccompanied) • Lam, Bun-Ching Three Easy Pieces (with electronics) • Lastres, Doris Magaly Ruiz Cuasi Danzón (with piano) Tres Piezas (with piano) • Ma, Youdao Fantasia on a Theme of Yada Meyrien (with piano/orchestra) - Jinan University Press (ISBN 9787566829207) • McCeary, Richard Deming Jr. -

Tuba Syllabus / 2003 Edition

74058_TAP_SyllabusCovers_ART_Layout 1 2019-12-10 10:56 AM Page 36 Tuba SYLLABUS / 2003 EDITION SHIN SUGINO SHIN Message from the President The mission of The Royal Conservatory—to develop human potential through leadership in music and the arts—is based on the conviction that music and the arts are humanity’s greatest means to achieve personal growth and social cohesion. Since 1886 The Royal Conservatory has realized this mission by developing a structured system consisting of curriculum and assessment that fosters participation in music making and creative expression by millions of people. We believe that the curriculum at the core of our system is the finest in the world today. In order to ensure the quality, relevance, and effectiveness of our curriculum, we engage in an ongoing process of revitalization, which elicits the input of hundreds of leading teachers. The award-winning publications that support the use of the curriculum offer the widest selection of carefully selected and graded materials at all levels. Certificates and Diplomas from The Royal Conservatory of Music attained through examinations represent the gold standard in music education. The strength of the curriculum and assessment structure is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of outstanding musicians and teachers from Canada, the United States, and abroad who have been chosen for their experience, skill, and professionalism. An acclaimed adjudicator certification program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in helping all people to open critical windows for reflection, to unleash their creativity, and to make deeper connections with others. -

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

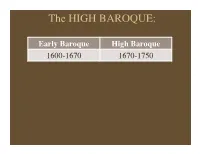

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Beethoven, Bagels & Banter

Beethoven, Bagels & Banter SUN / OCT 21 / 11:00 AM Michele Zukovsky Robert deMaine CLARINET CELLO Robert Davidovici Kevin Fitz-Gerald VIOLIN PIANO There will be no intermission. Please join us after the performance for refreshments and a conversation with the performers. PROGRAM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Trio in B-flat major, Op. 11 I. Allegro con brio II. Adagio III. Tema: Pria ch’io l’impegno. Allegretto Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) Quartet for the End of Time (1941) I. Liturgie de cristal (“Crystal liturgy”) II. Vocalise, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du Temps (“Vocalise, for the Angel who announces the end of time”) III. Abîme des oiseau (“Abyss of birds”) IV. Intermède (“Interlude”) V. Louange à l'Éternité de Jésus (“Praise to the eternity of Jesus”) VI. Danse de la fureur, pour les sept trompettes (“Dance of fury, for the seven trumpets”) VII. Fouillis d'arcs-en-ciel, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du Temps (“Tangle of rainbows, for the Angel who announces the end of time) VIII. Louange à l'Immortalité de Jésus (“Praise to the immortality of Jesus”) This series made possible by a generous gift from Barbara Herman. PERFORMANCES MAGAZINE 20 ABOUT THE ARTISTS MICHELE ZUKOVSKY, clarinet, is an also produced recordings of several the Australian National University. American clarinetist and longest live performances by Zukovsky, The Montréal La Presse said that, serving member of the Los Angeles including the aforementioned Williams “Robert Davidovici is a born violinist Philharmonic Orchestra, serving Clarinet Concerto. Alongside her in the most complete sense of from 1961 at the age of 18 until her busy performing schedule, Zukovsky the word.” In October 2013, he retirement on December 20, 2015. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS APRIL 12, 2021 | PAGE 1 OF 20 BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] INSIDE Tenille Arts Overcomes Multiple Challenges En Route To An Unlikely First Top 10 Stapleton, Tenille Arts won’t be taking home any trophies from the 2019, it entered the chart dated Feb. 15, 2020, at No. 59, just Barrett 56th annual Academy of Country Music (ACM) Awards on weeks before COVID-19 threw businesses around the world Rule Charts April 18 — competitor Gabby Barrett received the new female into chaos. Shortly afterward, Reviver was out of the picture. >page 4 artist honor in advance — but Arts has already won big by Effective with the chart dated May 2, 19th & Grand — headed overcoming an extraordinary hurdle to claim a precedent- by CEO Hal Oven — was officially listed as the lone associated setting top 10 single with her first bona label. Reviver executive vp/GM Gator Mi- fide hit. chaels left to form a consultancy in April Clint Black Arts, who was named a finalist for new 2020 and tagged Arts and 19th & Grand ‘Circles’ TV female when nominations were unveiled as his initial clients. Former Reviver vp Feb. 26, moves to No. 9 on the Country Air- promotion Jim Malito likewise shifted to >page 11 play chart dated April 17 in her 61st week 19th & Grand, using the same title. Four on the list. Co-written with producer Alex of the five current 19th & Grand regionals Kline (Terri Clark, Erin Enderlin) and Alli- are also working the same territory they son Veltz Cruz (“Prayed for You”), “Some- worked at Reviver. -

Wind Ensemble Repertoire

UNCG Wind Ensemble Programming April 29, 2009 Variations on "America" ‐ Charles Ives, arr. William Schuman and William Rhoads Symphonic Dances from West Side Story Leonard Bernstein, arr. Paul Lavender Mark Norman, guest conductor Children's March: "Over the Hills and Far Away” Percy Grainger Kiyoshi Carter, guest conductor American Guernica Adolphus Hailstork Andrea Brown, guest conductor Las Vegas Raga Machine Alejandro Rutty, World Premiere March from Symphonic Metamorphosis Paul Hindemith, arr. Keith Wilson March 27, 2009 at College Band Directors National Association National Conference, Bates Recital Hall, University of Texas at Austin Fireworks, Opus 8 Igor Stravinsky, trans. Mark Rogers It perched for Vespers nine Joel Puckett Theme and Variations, Opus 43a Arnold Schoenberg Shadow Dance David Dzubay Commissioned by UNCG Wind Ensemble Four Factories Carter Pann Commissioned by UNCG Wind Ensemble FuniculiFunicula Rhapsody Luigi Denza, arr. Yo Goto February 20, 2009 Fireworks, Op. 4 Igor Stravinsky, trans. Mark Rogers O Magnum Mysterium Morten Lauridsen H. Robert Reynolds, guest conductor Theme and Variations, Op. 43a ‐ Arnold Schoenberg Symphony No. 2 Frank Ticheli Frank Ticheli, guest conductor December 3, 2008 Raise the Roof ‐ Michael Daugherty John R. Beck, timpani soloist Intermezzo Monte Tubb Andrea Brown, guest conductor Shadow Dance David Dzubay Four Factories Carter Pann FuniculiFunicula Rhapsody Luigi Denza, arr. Yo Goto October 8, 2008 Fireworks, Opus 8 ‐ Igor Stravinsky, trans. Mark Rogers it perched for Vespers nine Joel Puckett Theme and Variations, Op. 43a Arnold Schoenberg Fantasia in G J.S. Bach, arr. R. F. Goldman Equus ‐ Eric Whitacre Andrea Brown, guest conductor Entry March of the Boyars Johan Halvorsen Fanfare Ritmico ‐ Jennifer Higdon May 4, 2008 Early Light Carolyn Bremer Icarus and Daedalus ‐ Keith Gates Emblems Aaron Copland Aegean Festival Overture Andreas Makris Mark A. -

James Dick Press Kit

James Dick Press Kit Information and Booking – Jan Lehman – 512.478.1131 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover….................................................…......................................................... 1 Table of Contents....................................…........................................................ 2 Biography................................................…........................................................ 3 Grey-Scale Photo...................................…........................................................ 4 References and Reviews........................…........................................................ 5 Concerto and Solo Repertoires …............…........................................................ 6 Chamber Music and Recordings............…........................................................ 7 Information and Booking – Jan Lehman – 512.478.1131 BIOGRAPHY Recognized as one of the truly important pianists of his generation, internationally renowned concert pianist and Steinway artist James Dick brings keyboard sonorities of captivation, opulence and brilliance to performances that radiate intellectual insight and emotional authenticity. Raised in Hutchinson Kansas, his talent moved him from the farm to the University of Texas Music Building and out to the world's great concert halls. He received a scholarship to the University of Texas in Austin, studying with Dalies Frantz. Later, he was a Fulbright Scholar and studied with Sir Clifford Curzon in England. Dick's early triumphs as a major