III.—Notes on Altered Igneous Rocks of Tintagel, North Cornwall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

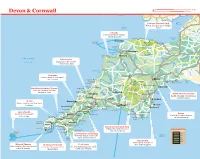

Devon & Cornwall

Devon & Cornwall 4444 Severn ROAD DISTANCES (miles) Exmoor National Park Estuary Note: Distances Watch red deer on a wildlife Bristol safari Newquay 80 are approximate Channel Penzance 108 31 Clovelly Plymouth 43 49 77 Devon’s prettiest village? Quite possibly St Ives 108 31 9 74 Lynmouth Bridgwater #\ Lynton #\ Bay Torquay 21 80 108 31 105 Porlock Ilfracombe #\ #\ Lundy #÷ Exmoor #\ Truro 86 12 27 55 24 86 Island National Dunster Park Croyde #\ Exford #\ Braunton #\ The Quantocks Barnstaple #] Barnstaple Exeter Newquay Penzance Plymouth St Ives Torquay Bay #\ Appledore T Dulverton #\ Heartland #\ Bideford aw Peninsula #\ Clovelly ATLANTIC OCEAN North Coast Find your own secret patch #\ of sand Widemouth Bude Bay T a Okehampton m #\ Eden Project a ^# r Exeter Experience the world’s Bossiney Boscastle #\ #÷ Sidmouth #\ #\ Beer Lyme HavenÙ# Chagford #\ #\ #\ Bay 44 biodiversity here Tintagel Dartmoor Branscombe National #\ Camelford #\ #\ Park Moretonhampstead Exmouth Lydford #] Port Polzeath #\ #\ Tamar Widecombe- Isaac #\ 44 Valley in-the-Moor Newquay Teignmouth #\ #\ Rock #] #\ Catch a wave in Cornwall’s Padstow Tavistock #\ South West Coast Path #\ #\ Start surf central Wadebridge Princetown Ashburton Bay Amble through breathtaking Bedruthandrut Bodmin #] coastal scenery Stepsps #\ Torquay Moor #\ Liskeard Newquay #] Eden #\ Tor Bay #æ Project Totnes ^# #\ Exeter Plymouth Brixham #\ Climb the Gothic towers St Ives Perranporth #\ St Austell Fowey Looe #\ Dartmouth #\#\ #\ #\ of the cathedral Delve into Cornwall’s artistic St Agnes #\ -

Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS CORNWALL COUNCIL VOTING AREA Referendum on the United Kingdom's membership of the European Union 1. A referendum is to be held on THURSDAY, 23 JUNE 2016 to decide on the question below : Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union? 2. The hours of poll will be from 7am to 10pm. 3. The situation of polling stations and the descriptions of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows : No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 301 STATION 2 (AAA1) 1 - 958 CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 301/1 STATION 1 (AAM4) 1 - 212 THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 302 CUDDRA W I HALL (AAA2) 1 - 430 BUCKLERS LANE HOLMBUSH ST AUSTELL PL25 3HQ 303 BETHEL METHODIST CHURCH (AAB1) 1 - 1,008 BROCKSTONE ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DW 304 BISHOP BRONESCOMBE SCHOOL (AAB2) 1 - 879 BOSCOPPA ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DT KATE KENNALLY Dated: WEDNESDAY, 01 JUNE, 2016 COUNTING OFFICER Printed and Published by the COUNTING OFFICER ELECTORAL SERVICES, ST AUSTELL ONE STOP SHOP, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 305 SANDY HILL ACADEMY (AAB3) 1 - 1,639 SANDY HILL ST AUSTELL PL25 3AW 306 STATION 2 (AAG1) 1 - 1,035 THE COMMITTEE ROOM COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK ROAD PL25 5DR 306/1 STATION 1 (APL3) 1 - 73 THE COMMITTEE ROOM CORNWALL COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK -

Bude | Tintagel | Camelford | Wadebridge | St Columb Major

Bude | Tintagel | Camelford | Wadebridge | St Columb Major | Truro showing connections to Newquay on route 93 95 Mondays to Saturdays except public holidays 92 95 93 95 93 93 95 93 95 93 95 93 95 93 95 93 93 95 93 Bude Strand 0847 1037 1312 1525 1732 Widemouth Bay Manor 0857 1047 1322 1542 1742 Poundstock crossroads 0900 1050 1325 1545 1745 Wainhouse Corner garage 0904 1054 1329 1549 1749 Crackington Haven Cabin Café 0912 1102 1337 1557 1757 Higher Crackington Post Office 0915 1105 1340 1600 1800 Tresparrett Posts 0919 1109 1344 1604 1804 Boscastle car park 0719 0929 1119 1354 1614 1814 Bossiney bus shelter 0730 0940 1130 1405 1625 1825 Tintagel visitor centre 0735 0945 1135 1410 1630 1830 Trewarmett 0741 0951 1141 1416 1636 1836 Camelford Methodist Church 0753 1003 1153 1428 1648 1848 Camelford Clease Road 0755 1005 1155 1430 1650 1850 Helstone opp bus shelter 0800 1010 1200 1435 1655 1855 St Teath opp Post Office 0805 1015 1205 1700 Trelill Barton cottages 0811 1021 1211 x 1706 x St Kew Highway phone box 0816 1026 1216 1444 1711 1904 Wadebridge opp School 0824 1034 1224 1452 1719 1912 Wadebridge The Platt 0827 1037 1227 1455 1722 1915 Wadebridge bus station arr 0829 1039 1229 1457 1724 1917 Wadebridge bus station dep 0707 0717 0847 1047 1237 1502 1732 1922 Wadebridge The Platt 0709 0719 0849 1049 1239 1504 1734 1924 x x x x x x x x Wadebridge Tesco 0712 0722 0852 1052 1242 1507 1737 1927 Royal Cornwall Showground 0714 0724 0854 1054 1244 1509 1739 1929 Winnards Perch 0721 0731 0901 1101 1251 1516 1746 1936 St Columb Major Old Cattle -

01841 532555 the Pottery, Trethevy £425,000

Jackie Stanley Estate Agents 1 North Quay Padstow Cornwall PL28 8AF t. 01841 532555 e: [email protected] Small Complex of Converted Traditional Barns The Pottery, Trethevy Far Reaching Cliff & Sea Views Close to St Nectans Glen Waterfall £425,000 Substantial Two Double Bedroom Detached Barn Conversion Smart Modern Interior Large Private Courtyard & Ample Off Road Parking Great Coastal Home with Excellent Letting Potential This substantial two bedroom detached former barn is part of a collection of high quality residential barn conversions, located within a beautiful courtyard setting & positioned on the North Cornish Coast with some lovely far reaching cliff & sea views. For further information about this property please visit our office or call us on 01841 532555 Registered Office VAT Registration No: 6759665 67 e. [email protected] Registered Office VAT Registration No: 6759665 67 e. [email protected] 1 North Quay Padstow Cornwall PL28 8AF Registered in England 4991702 w. jackie-stanley.co.uk 1 North Quay Padstow Cornwall PL28 8AF Registered in England 4991702 w. jackie-stanley.co.uk Jackie Stanley Estate Agents 1 North Quay Padstow Cornwall PL28 8AF t. 01841 532555 e. [email protected] This complex of newly converted traditional Cornish barns is superbly positioned in the coastal hamlet of Trethevy, conveniently situated between the historic village of Tintagel and the picturesque harbour village of Boscastle. The three individual barns are positioned in a slightly elevated spot with excellent views towards the cliffs of Bossiney Cove and to the ocean beyond. Found within a pleasant low maintenance courtyard setting, the three properties have been superbly and thoughtfully converted. -

Sallows Sallows Bossiney Road, Tintagel, Cornwall, PL34 0AL Village Centre 0.5 Miles – Bodmin 19.4 Miles – (A30) 18.9 Miles

Sallows Sallows Bossiney Road, Tintagel, Cornwall, PL34 0AL Village Centre 0.5 miles – Bodmin 19.4 miles – (A30) 18.9 miles Charming semi-detached property with the benefit of an annexe and sea views • Close to Amenities • 3 Bedrooms • Open Plan Sitting/Dining Room • Conservatory • Bathroom and Shower Room • 1 Bedroom Annexe • Garden • Garage and Parking Guide Price £459,950 SITUATION The property is situated in the coastal hamlet of Bossiney on the edge of the historic village of Tintagel. The village has numerous shops and facilities, including post office, general store, chemist, primary school, places of worship, doctors surgery, numerous pubs and restaurants and a wealth of amenities associated with a popular self-contained coastal village. The picturesque harbour village of Boscastle is approximately 6 miles to the north with similar amenities. The former market town of Launceston is approximately 19 miles away with access to the A30 trunk road which links the cathedral cities of Truro and Exeter. At Exeter there are superb shopping facilities, access to the M5 motorway network, mainline railway station serving London Paddington and international airport. DESCRIPTION A light and spacious semi-detached property which benefits from an adjoining one bedroom annexe. The property enjoys a peaceful, private location along a private road with views across the cricket pitch and sea beyond. ACCOMMODATION The accommodation is clearly illustrated on the floorplan overleaf and briefly comprises: a multi-paned double glazed door to the hallway with a half-glazed door leading to the inner hall which has a shower room with WC and wash hand basin. -

Devon & Cornwall

# e0 50 km Devon & Cornwall 444 0 25 miles Severn 444 Exmoor National Park Estuary Watch red deer on a wildlife Bristol safari Channel Clovelly Devon’s prettiest village? Quite possibly Lynton Lynmouth Bridgwater #\#\ Porlock Bay Ilfracombe #\ #\ Lundy ÷# Exmoor #\Dunster Island National Park Croyde #\ Exford #\ Braunton #\ The Quantocks #] Barnstaple Barnstaple \# Appledore Bay T Dulverton #\ Heartland #\ Bideford aw Peninsula #\ Clovelly A T L A N T I C Eden Project O C E A N Experience the world’s biodiversity here #\ Widemouth Bude Bay T Newquay a Okehampton m #\ Catch a wave in Cornwall’s a r ^# surf central Bossiney Boscastle Exeter #\ #\ Lyme HavenÙ# #÷ Chagford Sidmouth #\ Beer #\ #\ #\ Bay 44 Tintagel Dartmoor Branscombe National #\ \# Lydford #\ Park Moretonhampstead Port Isaac Camelford #] Exmouth #\ Widecombe- Gwithian & Godrevy Towans Polzeath #\ Tamar #\ 44 Valley in-the-Moor Wander Cornwall's finest Teignmouth #\ #\ Rock #\ stretch of sand Padstow Bodmin Tavistock #] #\ Start #\ Wadebridge Moor Princetown \#Ashburton Bay South West Coast Path Bedruthan Amble through breathtaking Steps Bodmin #\ coastal scenery #\ Liskeard #] Torquay #] #\ Tor St Ives Newquay Eden #æ Totnes Bay Delve into Cornwall’s artistic Project #] #\ heritage Brixham #\ #\ Plymouth Perranporth St Austell Fowey Looe #\ #\ #\ Dartmouth #\ #\ St Agnes #\ Charlestown Polperro Rame Bigbury- St Austell Peninsula Lost Gardens#æ Bay on-Sea Isles of Scilly Portreath #\ #\ #\ Kingsbridge #\ #\ of Heligan #\ St Ives Mevagissey Bantham #\ Exeter Relax on this remote -

Bude | Tintagel | Camelford | Wadebridge | St Columb Major

Bude | Tintagel | Camelford | Wadebridge | St Columb Major | Truro showing connections to Newquay on route 93 95 Mondays to Saturdays except public holidays 92 95 93 95 93 93 95 93 95 93 95 93 95 93 95 93 93 95 93 Bude Strand 0847 1037 1312 1525 1732 Widemouth Bay Manor 0857 1047 1322 1542 1742 Poundstock crossroads 0900 1050 1325 1545 1745 Wainhouse Corner garage 0904 1054 1329 1549 1749 Crackington Haven Cabin Café 0912 1102 1337 1557 1757 Higher Crackington Post Office 0915 1105 1340 1600 1800 Tresparrett Posts 0919 1109 1344 1604 1804 Boscastle car park 0719 0929 1119 1354 1614 1814 Bossiney bus shelter 0730 0940 1130 1405 1625 1825 Tintagel visitor centre 0735 0945 1135 1410 1630 1830 Trewarmett 0741 0951 1141 1416 1636 1836 Camelford Methodist Church 0753 1003 1153 1428 1648 1848 Camelford Clease Road 0755 1005 1155 1430 1650 1850 Helstone opp bus shelter 0800 1010 1200 1435 1655 1855 St Teath opp Post Office 0805 1015 1205 1700 Trelill Barton cottages 0811 1021 1211 x 1706 x St Kew Highway phone box 0816 1026 1216 1444 1711 1904 Wadebridge opp School 0824 1034 1224 1452 1719 1912 Wadebridge The Platt 0827 1037 1227 1455 1722 1915 Wadebridge bus station arr 0829 1039 1229 1457 1724 1917 Wadebridge bus station dep 0707 0717 0847 1047 1237 1502 1732 1922 Wadebridge The Platt 0709 0719 0849 1049 1239 1504 1734 1924 x x x x x x x x Wadebridge Tesco 0712 0722 0852 1052 1242 1507 1737 1927 Royal Cornwall Showground 0714 0724 0854 1054 1244 1509 1739 1929 Winnards Perch 0721 0731 0901 1101 1251 1516 1746 1936 St Columb Major Old Cattle -

Gardens Guide

Gardens of Cornwall map inside 2015 & 2016 Cornwall gardens guide www.visitcornwall.com Gardens Of Cornwall Antony Woodland Garden Eden Project Guide dogs only. Approximately 100 acres of woodland Described as the Eighth Wonder of the World, the garden adjoining the Lynher Estuary. National Eden Project is a spectacular global garden with collection of camellia japonica, numerous wild over a million plants from around the World in flowers and birds in a glorious setting. two climatic Biomes, featuring the largest rainforest Woodland Garden Office, Antony Estate, Torpoint PL11 3AB in captivity and stunning outdoor gardens. Enquiries 01752 814355 Bodelva, St Austell PL24 2SG Email [email protected] Enquiries 01726 811911 Web www.antonywoodlandgarden.com Email [email protected] Open 1 Mar–31 Oct, Tue-Thurs, Sat & Sun, 11am-5.30pm Web www.edenproject.com Admissions Adults: £5, Children under 5: free, Children under Open All year, closed Christmas Day and Mon/Tues 5 Jan-3 Feb 16: free, Pre-Arranged Groups: £5pp, Season Ticket: £25 2015 (inclusive). Please see website for details. Admission Adults: £23.50, Seniors: £18.50, Children under 5: free, Children 6-16: £13.50, Family Ticket: £68, Pre-Arranged Groups: £14.50 (adult). Up to 15% off when you book online at 1 H5 7 E5 www.edenproject.com Boconnoc Enys Gardens Restaurant - pre-book only coach parking by arrangement only Picturesque landscape with 20 acres of Within the 30 acre gardens lie the open meadow, woodland garden with pinetum and collection Parc Lye, where the Spring show of bluebells is of magnolias surrounded by magnificent trees. -

Tintagel Wills

Tintagel Wills and/or associated documents available from Kresen Kernow (formerly the Cornwall Record Office (CRO) and the National Archive (NA) Links are to the transcripts available from the parish page Source Ref. No. Title Date Proved CRO ACP/WR/184/103 Will indexes, Archdeaconry Court of Probate, Tintagel 1569-1610 CRO AP/R/4 Will of John Rawlyn alias Rundell of Tintagel 1601 CRO AP/H/34 Will of Margery Hockey of Tintagel 1602 CRO AP/T/36 Will of Lawrence Tynke, miller, of Tintagel 1602 CRO AP/N/17 Will of William Nichol of Tintagel 1605 CRO AP/S/109 Will of John Symons of Tintagel 1606 CRO AP/V/19 Will of John Veale, husbandman, of Trewarmet, Tintagel 1606 CRO AP/B/139 Will of William Brown of Tintagel 1606 CRO AP/M/96 Will of Christopher Martyn of Tintagel 1606 CRO AP/M/113 Will of Nicholas Morfall of Tintagel 1606 CRO AP/L/53 Will of Richard Locke of Tintagel 1606 CRO AP/A/39 Will of Thomas Avery of Tintagel 1607 CRO AP/J/84 Will of Phillip Jefordor Gefford alias Blagdon of Tintagel 1607 CRO AP/S/142 Will of Mary Symon of Tintagel 1607 CRO AP/G/75 Will of Roger Geake, husbandman, of Tintagel 1607 CRO AP/S/141 Will of John Symon of Tintagel 1607 CRO AP/M/118 Will of John Melorn of Tintagel 1607-1608 CRO AP/P/163 Will of William Prowte of Tintagel 1608 CRO AP/S/160 Will of Robert Strowt, husbandman, of Tintagel 1608 CRO AP/A/49 Will of Thomas Avery of Tintagel 1608-1609 CRO AP/S/185 Will of Mary Symon of Tintagel 1609 CRO AP/R/155 Will of Clement Rowbye, husbandman, of Tintagel 1609 CRO AP/J/120 Will of Margaret Judd, widow, of -

Merlin Messenger Your Place for News and Information

Merlin Messenger Your place for news and information Welcome to our new look died. The family, who have been extremely supportive to the charity since it opened, Merlin Messenger! chose to donate money from the funeral to the centre, requesting it be used for a specific This summer has been very busy at the centre. project. Our new Occupational Therapist Kath Smith and Exercise Trainer Helen Tite are making a real Centre Manager Loraine Long said, “When we difference to centre users complementing the were building the centre, one of the first people busy physiotherapy department. All our dedicated to welcome us was Ivor. I knew that we needed therapists show commitment, professionalism and to spend this money on a project which would the desire to help clients improve their quality reflect his warmth and would benefit all who of life. visited the centre” Paula our specialist Neurological Physiotherapist, For John the perfect thing to recreate was the is about to start her maternity leave and we wish Autumn / Winter Issue 08 beautiful Merlin icon. her and her partner Dave every happiness with the The finished result; a glistening and swirling forthcoming arrival of their little girl. sculpture in the striking brand colour of deep We welcome Melissa King who is covering Paula purple made from 80 feet of hand rolled iron. whilst she is on leave. Melissa is an experienced I think you will agree that it is an amazing grade 7 Neurological Physiotherapist who has piece of work and complements our beautiful moved down from Surrey to be with us. -

Post-Conquest Medieval

Medieval 12 Post-Conquest Medieval Edited by Stephen Rippon and Bob Croft from contributions by Oliver Creighton, Bob Croft and Stephen Rippon 12.1 Introduction economic transformations reflected, for example, in Note The preparation of this assessment has been the emergence, virtual desertion and then revival of an hampered by a lack of information and input from some urban hierarchy, the post-Conquest Medieval period parts of the region. This will be apparent from the differing was one of relative social, political and economic levels of detail afforded to some areas and topics, and the continuity. Most of the key character defining features almost complete absence of Dorset and Wiltshire from the of the region – the foundations of its urban hier- discussion. archy, its settlement patterns and field systems, its The period covered by this review runs from the industries and its communication systems – actually Norman Conquest in 1066 through to the Dissolu- have their origins in the pre-Conquest period, and tion of the monasteries in the 16th century, and unlike the 11th to 13th centuries simply saw a continua- the pre-Conquest period is rich in both archaeology tion of these developments rather than anything radi- (including a continuous ceramic sequence across the cally new: new towns were created and monas- region) and documentary sources. Like every region teries founded, settlement and field systems spread of England, the South West is rich in Medieval archae- out into the more marginal environments, industrial ology preserved within the fabric of today’s historic production expanded and communication systems landscape, as extensive relict landscapes in areas of were improved, but all of these developments were the countryside that are no longer used as inten- built on pre-Conquest foundations (with the excep- sively as they were in the past, and buried beneath tion of urbanisation in the far south-west). -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Williams, Richard Title: County and municipal government in Cornwall, Devon, Dorset and Somerset 1649- 1660. General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. COUNTY AND MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENT IN CORNWALL, DEVON, DORSET AND SOMERSET 1649-1660 by RICHARD WILLIAMS xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx A THESIS Submitted to the University of Bristol for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1981 XXXXXXX*1XXXXXXXXXXX County and Municipal Government in Cornwall, Devon, Dorset and Somerset 1649-1660.