Character in the Age of Adam Smith by Shannon Frances Chamberlain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Raeburn : English School

NOVEMBER, 1905 RAEBURN PRICE, 15 CENTS anxa 84-B 5530 Jjpueiniipntljlu. RAEBURN J3atK^anO*<iuU&C[ompany, Xtybligfjerg 42<H)auncji^treEt MASTERS IN ART A SERIES OF ILLUSTRATED MONOGRAPHS: ISSUED MONTHLY PART 71 NOVEMBER, 1905 VOLUME 6 a 1 1 u t* 1X CONTENTS Plate I. Portrait of Mrs. Strachan Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, Mass. Plate II. Portrait of Lord Newton National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh Plate III. Mrs. Ferguson and Children Owned by R. C. Munroe-Ferguson, Esq. Plate IV. Portrait of Sir Walter Scott Collection of the Earl of Home Plate V. Portrait of Sir John Sinclair Owned by Sir Tollemache Sinclair Plate VI. Portrait of Mrs. Campbell of Balliemore National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh Plate VII. Portrait of John Wauchope National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh Plate VIII. Portrait of Mrs. Scott-Moncrieff National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh Plate IX. Portrait of James Wardrop of Torbanehill Owned by Mrs. Shirley Plate X. The Macnab Owned by Hon. Mrs. Baillie Hamilton Portrait of Raeburn by Himself : Owned by Lord Tweedmouth Page 22 The Life of Raeburn Page 23 ’ Abridged from Edward Pinnington's ‘ Sir Henry Raeburn The Art of Raeburn Page 30 Criticisms by Armstrong, Pinnington, Brown, Van Dyke, Cole, Muther, Stevenson The Works of Raeburn : Descriptions of the Plates and a List of Paintings Page 36 Raeburn Bibliography Page 42 Photo-angravings by C. J. Ptttrs Son: Boston. Prass-work by tht Evantt Prass : Boston complata pravious ba ba consultad library A indax for numbars will found in tba Rtadar's Guida to Pariodical Litaratura , which may in any PUBLISHERS’ ANNOUNCEMENTS SUBSCRIPTIONS: Yearly subscription, commencing with any number of the 1905 volume, $1.50, payable in advance, postpaid to any address in the United States or Canada. -

Rossyln Scenic Lore

ROSSLYN'S SCENIC LORE THE NORTH ESK RIVER OF ROMANCE "It is telling a tale that has been repeated a thousand times, to say, that a morning of leisure can scarcely be anywhere more delight- fully spent than hi the woods of Rosslyn, and on the banks of the Esk. Rosslyn and its adjacent scenery have associations, dear to the antiquary and historian, which may fairly entitle it to precedence over every other Scottish scene of the same kind." SIR WALTER SCOTT (" Provincial Antiquities of Scotland.") OF ROMANCE abound in Scotland, and RIVERSthe North Esk is one of them. From its source high up among the Pentland Heights near the Boarstane and the boundary line between Midlothian and Tweeddale, it is early gathered into a reservoir, whose engineer was Thomas Stevenson, father of Robert Louis Stevenson, constructed in 1850 to supply water and power used in the paper mills on the river's banks. Passing through Carlops, once a village of weavers, it flows on through the wooded gorge of Habbie's Howe and the woods surrounding Penicuik House, on to " Rosslyn's rocky glen," and Hawthornden, Melville Castle and Dalkeith Palace, entering the Firth of Forth at Musselburgh. Alas that the clear sparkling waters of the moorland stream should be so spoiled by the industries of the Wordsworth's valley." Dorothy Diary entry is still true the water of the stream is dingy and muddy." Modern legislation on river pollution is sadly lacking. 75 " I never passed through a more delicious dell than the Glen of wrote and of the Rosslyn," " Dorothy; river it has been written No stream in Scotland can boast such a varied succession of the most interesting objects, as well as the most romantic and beautiful scenery." It is associated with some of the most famous men in Scottish literature who have lived on its banks, and has inspired the muse of some of Scotland's best poets. -

The Problem of Sentimentalism in Mackenzie's the Man of Feeling

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 11 1988 A "sickly sort of refinement": The rP oblem of Sentimentalism in Mackenzie's The aM n of Feeling William J. Burling Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Recommended Citation Burling, William J. (1988) "A "sickly sort of refinement": The rP oblem of Sentimentalism in Mackenzie's The aM n of Feeling," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 23: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol23/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. William J. Burling A "sickly sort of refinement": The Problem of Sentimentalism in Mackenzie's The Man of Feeling Henry Mackenzie's The Man of Feeling, enormously popular when first published in 1771, was acknowledged by an entire generation of readers as the ultimate representation of the sentimental ethos. But outright contradiction now pervades critical discussion of the novel, with interpretation splitting on two central questions: Is Harley, the hero, an ideal man or a fool? And is the novel sympathetic to sentimentalism or opposed to it? The antithetical critical responses to The Man of Feeling may be resolved, however, when we recognize that Mackenzie was neither completely attacking nor condoning sentimentalism in toto. He was attempting to differentiate what he considered to be attributes of genuine and desirable humane sensitivity from those of the affected sentimentality then au courant in the hypocritical beau monde. -

Adam Smith in Love · Econ Journal Watch : Abbe Colbert, James Currie, Janet Douglas, Lady Frances, David Hume, Henry Mackenzie

Discuss this article at Journaltalk: https://journaltalk.net/articles/6031/ ECON JOURNAL WATCH 18(1) March 2021: 127–155 Adam Smith in Love F. E. Guerra-Pujol1 LINK TO ABSTRACT Is any resentment so keen as what follows the quarrels of lovers, or any love so passionate as what attends their reconcilement? —Adam Smith (1980a/1795, 36) Was Adam Smith speaking from personal experience when he posed those questions?2 Here I report on my investigations into the matter. An investigation into someone’s love life is not the sort of endeavor that Smith would have ever undertaken. At the same time, if someone had ever produced such a report on, say, Montaigne or Grotius, we can imagine Smith glancing at it. The authors we most admire and learn from are human beings, and their character, personality, and private lives often figure into our understandings of their works. In the present report on Smith’s love life, I do not turn to interpreting Smith’s works, notably The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which contains several substantive passages about romantic love and about lust and licentious- ness.3 Instead, I presuppose that the reader has a natural and healthy curiosity about Smith’s personal life, including his love life. 1. University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL 32816. I thank Alain Alcouffe and three anonymous reviewers for their comments, clarifications, and suggestions. 2. This quotation appears in Section 1 of Smith’s essay on “The History of Astronomy.” Although “The History of Astronomy” was first published in 1795 along with some other writings of Smith, it is more likely than not that Smith first wrote this particular essay during his young adult years prior to his appointment at the University of Glasgow in 1751 (see Luna 1996, 133, 150 n.3). -

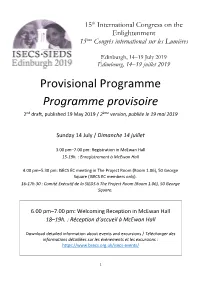

Programme19may.Pdf

15th International Congress on the Enlightenment 15ème Congrès international sur les Lumières Edinburgh, 14–19 July 2019 Édimbourg, 14–19 juillet 2019 Provisional Programme Programme provisoire 2nd draft, published 19 May 2019 / 2ème version, publiée le 19 mai 2019 Sunday 14 July / Dimanche 14 juillet 3.00 pm–7.00 pm: Registration in McEwan Hall 15-19h. : Enregistrement à McEwan Hall 4.00 pm–5.30 pm: ISECS EC meeting in The Project Room (Room 1.06), 50 George Square (ISECS EC members only). 16-17h.30 : Comité Exécutif de la SIEDS à The Project Room (Room 1.06), 50 George Square. 6.00 pm–7.00 pm: Welcoming Reception in McEwan Hall 18–19h. : Réception d’accueil à McEwan Hall Download detailed information about events and excursions / Télécharger des informations détaillées sur les événements et les excursions : https://www.bsecs.org.uk/isecs-events/ 1 Monday 15 July / Lundi 15 juillet 8.00 am–6.30 pm: Registration in McEwan Hall 8-18h.30 : Enregistrement à McEwan Hall 9.00 am: Opening ceremony and Plenary 1 in McEwan Hall 9h. : Cérémonie d’ouverture et 1e Conférence Plénière à McEwan Hall Opening World Plenary / Plénière internationale inaugurale Enlightenment Identities: Definitions and Debates Les identités des Lumières: définitions et débats Chair/Président : Penelope J. Corfield (Royal Holloway, University of London and ISECS) Tatiana V. Artemyeva (Herzen State University, Russia) Sébastien Charles (Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Canada) Deidre Coleman (University of Melbourne, Australia) Sutapa Dutta (Gargi College, University of Delhi, India) Toshio Kusamitsu (University of Tokyo, Japan) 10.30 am: Coffee break in McEwan Hall 10h.30 : Pause-café à McEwan Hall 11.00 am, Monday 15 July: Session 1 (90 minutes) 11h. -

Download History of the Mackenzies

History Of The Mackenzies by Alexander Mackenzie History Of The Mackenzies by Alexander Mackenzie [This book was digitized by William James Mackenzie, III, of Montgomery County, Maryland, USA in 1999 - 2000. I would appreciate notice of any corrections needed. This is the edited version that should have most of the typos fixed. May 2003. [email protected]] The book author writes about himself in the SLIOCHD ALASTAIR CHAIM section. I have tried to keep everything intact. I have made some small changes to apparent typographical errors. I have left out the occasional accent that is used on some Scottish names. For instance, "Mor" has an accent over the "o." A capital L preceding a number, denotes the British monetary pound sign. [Footnotes are in square brackets, book titles and italized words in quotes.] Edited and reformatted by Brett Fishburne [email protected] page 1 / 876 HISTORY OF THE MACKENZIES WITH GENEALOGIES OF THE PRINCIPAL FAMILIES OF THE NAME. NEW, REVISED, AND EXTENDED EDITION. BY ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, M.J.I., AUTHOR OF "THE HISTORY OF THE MACDONALDS AND LORDS OF THE ISLES;" "THE HISTORY OF THE CAMERONS;" "THE HISTORY OF THE MACLEODS;" "THE HISTORY OF THE MATHESONS;" "THE HISTORY OF THE CHISOLMS;" "THE PROPHECIES OF THE BRAHAN SEER;" "THE HISTORICAL "TALES AND LEGENDS OF THE HIGHLAND CLEARANCES;" "THE SOCIAL STATE OF THE ISLE OF SKYE;" ETC., ETC. LUCEO NON URO INVERNESS: A. & W. MACKENZIE. MDCCCXCIV. PREFACE. page 2 / 876 -:0:- THE ORIGINAL EDITION of this work appeared in 1879, fifteen years ago. It was well received by the press, by the clan, and by all interested in the history of the Highlands. -

Sir Walter Scott by John Gibson Lockhart

THE LIFE OF SIR WALTER SCOTT BY JOHN GIBSON LOCKHART VOLUME VII EDINBURGH PRINTED BY T. AND A. CONSTABLE FOR T. C. AND E. C. JACK CAUSEWAYSIDE 1902 : CONTENTS OF VOLUME VII CHAPTER LV. 1822 William Erskine promoted to the Bench : Joanna Baillie's Miscellany : Halidon Hill and Macduft^s Cross : Letters to Lord Montagu : Last Portrait by Raeburn : Constable's Letter on the appear- ance of the Fortunes of Nigel : Halidon Hill published ........ CHAPTER LVI. 1822 Repairs of Melrose Abbey : Letters to Lord Montagu and Miss Edgeworth : King George IV. visits Scotland : Celtic mania : Mr. Crabbe in Castle Street : Death of Lord Kinnedder : Departure of the King : Letters from Mr. Peel and Mr. Croker CHAPTER LVII. 1822-1823 Mons Meg: Jacobite Peerages: Invitation from the Galashiels Poet : Progress of Abbotsford House Letters to Joanna Baillie, Terry, Lord Montagu, etc.: Completion and Publication of Peveril of the Peak 78 V :::: CONTENTS CHAPTER LVIII. 1823 PAOE Quentin Durward in progress: Letters to Constable, of Waverley and and Dr. Dibdin : The Author the Roxburghe Club: The Bannaityne Club founded: Scott Chairman of the Edinburgh Oil Gas Company, etc.: Mechanical Devices at Abbotsford: Gasometer: Air-Bell, etc. etc.: The Bellenden Windows 117 CHAPTER LIX. 1823 Quentin Durward published: Transactions with Con- stable : Dialogues on Superstition proposed Article on Romance written: St. Ronan's Well ' ' begun : Melrose in July —Abbotsford visited by Miss Edgeworth, and by Mr. Adolphus: His Memoranda : Excursion to AUanton : Anecdotes Letters to Miss Baillie, Miss Edgeworth, Mr. Terry, etc. : Publication of St. Ronan's Well . 147 CHAPTER LX. 1824 Publication of Redgauntlet : Death of Lord Byron ' Library and Museum : The Wallace Chair ' House-Painting, etc. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part One ISBN 0 902 198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART I A-J C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

The Parish of Colinton

THE pflHiSH OF GOiiijlTOH FROM An Early Period to the Present Day, BY DAVID SHANKIE. EDINBURGH: PRINTED BY JOHN WILSON, 104 High Street. 1902. l.tt>y ^'y^'^'^ ''^^^^J^^ Cop// of Fird l\uje Kirk Session lleconh, Dated 7th September 1051. YE BUKE OF YE PAROCHE & KIRK OF HAILES ALIAS COLLINGTOUNE. DEDICATION. To the REV. NORMAN C. MAGFARLANE, Free Church Manse, JUNIPER GREEN. Much Respected Sir, Although I never mentioned the subject in any former letter I have had the honour of addressing to you, it has long been my intention to give you a brief sketch, or might I say miniature history of the Parish in which you have the honour to be a minister of the Gospel, and in which I have every reason to suppose you are deeply interested. Conscious, however, of my own limited capacity for the compilation of such a sketch, I thought it expedient not to mention its existence until the task had been in a manner completed. The following pages were written in the interval of other avocations, and having found much enjoyment in the compilation, I have much pleasure in giving the result to you in the hope that they may be a source of instruction and amusement in an idle hour. You will observe that an attempt has been made to give a general view of the Parish history with a selec- tion of what may be its more picturesque and prominent features. And now my friendly Aristarchus, I have made my bow, and would commend you to the perusal of the following small, though it is to be hoped, not uninterest- ing selection of facts. -

Mourning Scotland: in Memoriam Susan Manning Adriana Neagu

Mourning Scotland: In Memoriam Susan Manning Adriana Neagu, Babeș-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca The beginning of the year 2013 found the Edinburgh academic community in mourning, following the passing, within a fortnight, of two of its dearest and most dedicated senior members, late Professor Susan Manning and Dr. Gavin Wallace, leading figures in Scottish literary culture, whom I’ve both had the enormous privilege of knowing. Profoundly committed to the cause of Scottish arts and studies, they were an inspiration to, and acted as intellectual catalysts for the Edinburgh literary and artistic circles. If ever human character and professional excellence found themselves in symbiotic relationship, it was in these unique scholars who touched the lives of so many of their peers, leaving an indelible mark on their community. The news of their passing greatly saddened Scottish academia and publishing industry, Professor Manning and Dr. Wallace being continuously honored in countless tributes for their exemplary work as researchers, public servants and educators since. Born in Glasgow, on 24th December 1953, Susan Manning died in Edinburgh, on 15th January 2013. She was Grierson Professor of English Literature and, for the past 7 years, Director of the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities (IASH) at the University of Edinburgh. A sparkling literary critic and historian, she was an authority on Eighteenth century literature and Scottish-Transatlantic relations, serving as a mentor to several generations of young scholars. She was a Board Member and President of the Eighteenth-Century Scottish Studies Society and with Dr. Nicholas Phillipson, she directed a three-year research project on The Science of Man in Scotland, funded by the Leverhulme Trust. -

“Harry the Ninth (The Uncrowned King of Scotland)”

“Harry the Ninth (The Uncrowned King of Scotland)” Henry Dundas and the Politics of Self-Interest, 1790-1802 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in History. Sam Gribble 307167623 University of Sydney October 2012 Abstract The career of Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville underscores the importance of individual self-interest in British public life during the 1790-1802 Revolutionary Wars with France. Examining the political intrigue surrounding Dundas’ 1806 impeachment, the manner in which he established his political power, and contemporary critiques of self-interest, this thesis both complicates and adds nuance to understandings of the political culture of ‘Old Corruption’ in the late-Georgian era. As this thesis demonstrates, despite the wealth of opportunities for personal enrichment, individual self-interest was not always focused on obtaining sinecures and financial windfalls. Instead, men like Henry Dundas were primarily focused upon amassing their own political power. In the inherently chaotic politics of the period, the self-seeking concerns of individuals like Henry Dundas, very quickly could, and indeed did, become the thread upon which the whole British political system turned. 2 Acknowledgments My thanks go first and foremost my supervisor, Dr Kit Candlin. His guidance, advice and expertise were vital in devising and writing this thesis, as was his unerring ability to ensure that I came away from our meetings enthusiastic about the task at hand. I would also like to thank Professor Robert Aldrich and Dr Lyn Olsen for their research seminars, both of which made me a better student and historian.