MINUTES of the AUTUMN SESSION, Geneva, 17-19 October

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Parliament LARRDIS (L.C.)/2012

he TIndian Parliament LARRDIS (L.C.)/2012 © 2012 Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Fourteenth Edition). LARRDIS (L.C.)/2012 he © 2012 Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi TIndian Parliament Editor T. K. Viswanathan Secretary-General Lok Sabha Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Fourteenth Edition). Lok Sabha Secretariat New Delhi Foreword In the over six decades that our Parliament has served its exalted purpose, it has witnessed India change from a feudally administered colony to a liberal democracy that is today the world's largest and also the most diverse. For not only has it been the country's supreme legislative body it has also ensured that the individual rights of each and every citizen of India remain inviolable. Like the Parliament building itself, power as configured by our Constitution radiates out from this supreme body of people's representatives. The Parliament represents the highest aspirations of the people, their desire to seek for themselves a better life. dignity, social equity and a sense of pride in belonging to a nation, a civilization that has always valued deliberation and contemplation over war and aggression. Democracy. as we understand it, derives its moral strength from the principle of Ahimsa or non-violence. In it is implicit the right of every Indian, rich or poor, mighty or humble, male or female to be heard. The Parliament, as we know, is the highest law making body. It also exercises complete budgetary control as it approves and monitors expenditure. -

Achievements of 1St Year of 17Th Lok

1 Hkkjrh; laln PARLIAMENT OF INDIA 2 PREFACE Indian democracy is the largest working democracy in the world. The identity of our pluralistic society, democratic traditions and principles are deeply rooted in our culture. It is in the backdrop of this rich heritage that India had established itself as a democratic republic after its independence from the colonial rule in the preceding century. Parliament of India is the sanctum sanctorum of our democratic system. Being the symbol of our national unity and sovereignty, this august institution represents our diverse society. Our citizens actively participate in the sacred democratic processes through periodic elections and other democratic means. The elected representatives articulate their hopes and aspirations and through legislations, work diligently, for the national interest and welfare of the people. This keeps our democracy alive and vibrant. In fact, people’s faith in our vibrant democratic institutions depends greatly upon the effectiveness with which the proceedings of the House are conducted. The Chair and the Members, through their collective efforts, give voice to the matters of public importance. In fact, the Lower House, Lok Sabha, under the leadership and guidance of the Hon’ble Speaker, is pivotal to the fulfillment of national efforts for development and public welfare. The 17th Lok Sabha was constituted on 25 May 2019 and its first sitting was held on 17 June 2019. The Hon’ble Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi, moved the motion for election of Shri Om Birla as the new Speaker of the Lok Sabha on 19 June 2019, which was seconded by Shri Rajnath Singh. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ______VOLUME LXVII NO.1 MARCH 2021 ______

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXVII NO.1 MARCH 2021 ________________________________________________________ LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI ___________________________________ THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION VOLUME LXVII NO.1 MARCH 2021 CONTENTS ADDRESSES PAGE Address on 'BRICS Partnership in the Interest of Global Stability, General 1 Safety and Innovative Growth: Parliamentary Dimension' at the Sixth BRICS Parliamentary Forum by the Speaker, Lok Sabha on 27 October 2020 Addresses of High Dignitaries at the 80th All India Presiding Officers' Conference, 4 Kevadia, Gujarat on 25-26 November 2020 Address Delivered by the Speaker, Lok Sabha, Shri Om Birla 5 Address Delivered by the Vice-President, Shri M. Venkaiah Naidu 7 Address Delivered by the President, Shri Ram Nath Kovind 13 Address Delivered by the Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi 18 Function for Laying the Foundation Stone for New Parliament Building in New 25 Delhi on 10 December 2020 Address Delivered by the Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi 25 Message from the President, Shri Ram Nath Kovind 32 Message from the Vice-President, Shri M. Venkaiah Naidu 33 SHORT NOTES A New Parliament for New India 34 PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES 39 Conferences and Symposia 39 Birth Anniversaries of National Leaders 41 Parliamentary Research & Training Institute for Democracies (PRIDE) 43 Members’ Reference Service 46 PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 47 SESSIONAL REVIEW 57 State Legislatures 57 RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 58 APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted by the committees of Lok Sabha 62 during 1 October to 31 December 2020 II. Statement showing the work transacted by the committees of Rajya Sabha 64 during 1 October to 31 December 2020 III. -

Lok Sabha Secretariat Publications Available for Sale at Sales Counter, Reception Office, Parliament House (Tel

LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT PUBLICATIONS AVAILABLE FOR SALE AT SALES COUNTER, RECEPTION OFFICE, PARLIAMENT HOUSE (TEL. NO. 23034726). FOR FURTHER DETAILS CONTACT SALES & RECORDS BRANCH (TEL. NO. 23034495/96) Name of Publication Price (in Rs.) Sl.No English Hindi version version 1 2 3 4 1. Abstract Series (1- 44 ) - Parliamentary Procedure 684/- 684/- 2. Anti-Defection Law in India and the Commonwealth 2400/- - 3. Babu Jagjivan Ram 1000/- - 4. Calligraphed copy of the Constitution 1310/- 2300/- 5. Constitution of India 625/- 625/- 6. Constitution of India 525/- 525/- 7. Conferment of Outstanding Parliamentarian Awards 75/- 75/- 8. Constituent Assembly Debate 4000/- 4000/- 9. Constitution Amendment in India 3500/- 3500/- 10. Constitution of India in Percept & Practice 895/- - 11. Council of Ministers (1947-2015) 500/- 500/- 12. Council of Ministers 15/- 15/- 13. Chandra Sekhar in Parliament 1200/- 1200/- 14. Dada Saheb Mavalankar-Father of Lok Sabha 200/- 100/- 15. Dictionary of Constitutional And Parliamentary Terms 300/- - 16. Directions by the Speaker 85/- 75/- 17. Discipline and Decorum in Parliament and State 300/- 300/- Legislature 18. Disqualification of Members on ground of Defection 45/- 45/- April, 2014(English) 19. Fifty years of Indian Parliament 1500/- 1500/- 20. Fifty Years of Indian Parliamentary Democracy 300/- 300/- 21. Finance Ministers’ Budget Speeches 1947-2011 (Vol. I, II 2500/- - & III) 22. Glossary of Idioms (English - Hindi) 180/- - 23. Glossary of Idioms (Urdu - English) 220/- - 24. Government and Parliament 130/- 130/- 25. Handbook for Members Lok Sabha 112/- 112/- 26. Hiren Mukerjee in Parliament 800/- - 27. Honouring National Leaders-Statues and Portraits in 800/- 800/- Parliament Complex 28. -

Standing Committee on Energy 12 (2020 -21)

STANDING COMMITTEE ON ENERGY 12 (2020 -21) SEVENTEENTH LOK SABHA MINISTRY OF POWER (Action-taken by the Government on the recommendations contained in the Forty-Third Report (16th Lok Sabha) on ‘Hydro Power’) TWELFTH REPORT LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI March, 2021/ Phalguna, 1942 (Saka) THIRTY NINTHREPORT NINTH REPORT 1 TWELFTH REPORT STANDING COMMITTEE ON ENERGY (2020-21) (SEVENTEENTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF POWER (Action-taken by the Government on the recommendations contained in the Forty-Third Report (16th Lok Sabha) on ‘Hydro Power’) Presented to Lok Sabha on 19th March, 2021 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 19th March, 2021 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI March, 2021/ Phalguna, 1942 (Saka) 2 COE NO. 327 Price: Rs. © 2020 by Lok Sabha Secretariat Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Sixteenth Edition) and Printed by_____________. 3 CONTENTS COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE (2020-21)…………………… 5 INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………… 6 CHAPTER I Report ……………………………………………… 7 CHAPTER II Observations/ Recommendations which have been 14 accepted by the Government CHAPTER III Observations/Recommendations which the Committee 27 do not desire to pursue in view of the Government’s replies CHAPTER IV Observations/ Recommendations in respect of which 28 replies of Government have not been accepted by the Committee and require reiteration CHAPTER V Observations/ Recommendations in respect of which 29 final replies of the Government are still awaited APPENDICES I Minutes of the Sitting of the Committee held on 30 18th March, 2021. II Analysis of Action Taken by the Government on the 32 Observations/ Recommendations contained in the Forty-Third Report (16th Lok Sabha) of the Standing Committee on Energy. -

Chapter Vi Parliament Library and Reference, Research, Documentation and Information Service (Larrdis) 75

CHAPTER VI PARLIAMENT LIBRARY AND REFERENCE, RESEARCH, DOCUMENTATION AND INFORMATION SERVICE (LARRDIS) 75. Objectives of the Service.—The primary objective of the Parliament Library and Reference, Research, Documentation and Information Service (LARRDIS) is to cater to the multifarious information needs of members of both the Houses of Parliament and provide, inter alia, research and reference material on legislative and other important issues coming up for discussion before the two Houses— the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha. To achieve this objective, the Service consists of professional and non-professional staff and is divided into seven Divisions: (i) Library Division; (ii) Reference Division; (iii) Research and Information Division; (iv) Media Relations Division; (v) Parliament Museum and Archives Division; (vi) Bureau of Parliamentary Studies and Training; and (vii) Computer (Hardware & Software) Management Branch (Software Unit). These Divisions have been further subdivided into various functional Wings and Sections with well-defined duties and spheres of work. 76. Research and Information Division.—The research and information services for Members of Parliament are provided by the Research and Information and Members’ Reference Divisions. Officers and staff in the Research and Information Division are categorized into the following specialised functional Wings/Sections: (i) Economic and Financial Affairs Wing; (ii) Educational and Scientific Affairs Wing; (iii) Journal of Parliamentary Information (JPI) Section; (iv) Legal and -

Introduction:- While Replying to Questions In

Introduction:- While replying to questions in the House or during discussions on Bills, Resolutions, Motions etc., Ministers on several occasions give assurances, undertakings or promises either to consider a matter, take action or furnish information later. The Standard List of forms constituting Assurances, may be seen at Annexure-I. In order to ensure that these assurances etc., are implemented and in a reasonable time, the Lok Sabha has constituted a Committee on Government Assurances with a view to institutionalizing the procedure to ensure the fulfillment of promises and undertakings given from time to time by the Minister on the floor of the House. Constitution of the Committee:- Until 1953, there was no institutional arrangement to pursue the assurances, promises etc., given by the Minister on the floor of the House and it was left to each individual Member to keep watch on the assurances/promises made by the Ministers. On 1 December, 1953 the Speaker nominated the first Committee on Government Assurances with six Members on it. The strength of the Committee was later on increased to fifteen Members on 13 May, 1954 by the Hon'ble Speaker. The Chairman/Chairperson is appointed by the Speaker from amongst the Members of the Committee. A Minister is not nominated as a Member of the Committee and if a member after his nomination to the Committee is appointed a Minister, he ceases to be a member of the Committee from the date of such appointment. The term of office of the members of the Committee shall not exceed one year from the date of its constitution. -

Speaker: Roles and Responsibility

In Depth – Speaker: Roles and Responsibility drishtiias.com/printpdf/in-depth-speaker-roles-and-responsibility Watch Video At: https://youtu.be/qZ5l31_N1hQ Bharatiya Janata Party's (BJP) MP Om Birla was unanimously elected as the Speaker of the 17th Lok Sabha on 19th June 2019. Since the Indian System of Government follows the Westminster Model, the Parliamentary proceedings of the country are headed by a presiding officer, who is called the Speaker. India’s first Prime Minister Pt. Jawahar Lal Nehru had said that in a parliamentary democracy, the Speaker represents the dignity and the freedom of the House and because the House represents the country, the speaker in a way becomes the symbol of the country’s freedom and liberty. 1/6 Speaker of the Lok Sabha The Lok Sabha, which is the highest legislative body in the country, chooses its Speaker who presides over the day to day functioning of the House. Electing the Speaker of the House is one of the first acts of newly constituted House. The office of the Speaker is a Constitutional Office. The Speaker is guided by the constitutional provisions and the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha. The Speaker is placed very high in the Warrant of Precedence in the country i.e. at rank 6. Adequate Powers are vested in the office of the Speaker to help her/him in the smooth conduct of parliamentary proceedings. The constitution provides that the Speaker’s salary and allowances are not to be voted by the Parliament and are to be charged on the Consolidated Fund of India. -

Members' Services Branch

Parliament of India Rajya Sabha SECTIONAL MANUAL OF OFFICE PROCEDURE (SMOP) MEMBERS’ SERVICES BRANCH Rajya Sabha Secretariat (Members’ Services Branch) June, 2010 Parliament of India Rajya Sabha SECTIONAL MANUAL OF OFFICE PROCEDURE (SMOP) MEMBERS’ SERVICES BRANCH Rajya Sabha Secretariat (Members’ Services Branch) June, 2010 First Edition June, 2010 Rajya Sabha Secretariat http://parliamentofindia.nic.in email:[email protected] PRICE : RS. 90/- P R E F A C E Sectional Manuals of Office Procedure (SMOP) for various Sections/Branches in the Rajya Sabha Secretariat are being brought out for the first time to provide an insight into the working of different Sections/Branches of the Secretariat and the procedure followed for disposal of work. A consolidated SMOP entitled “Members Services Branch” for MS&A Branch, MA Section, Conference & Protocol Section and Stenographers’ Pool is part of this exercise. The publication provides the procedure followed in disposal of various items of work dealt with by these Sections/Branches. This publication is intended to serve as a guide for the staff and officers dealing with day-to-day functioning of these units. 2. Care has been taken to make the Manual comprehensive and up-to-date. It is hoped that the publication would be found useful by the staff and officers of the Secretariat. 3. Suggestions, if any, for improvement of this publication are welcome. NEW DELHI, V. K. AGNIHOTRI, June, 2010 Secretary-General. (i) C O N T E N T S PAGES M.S. & A. Branch 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 2 Functions and Responsibilities ................................................................................ 1-2 3.1 Salary Bills of Hon’ble Chairman, Deputy Chairman, Leader of Opposition, Members and their P.As. -

Parliamentary Practices : Secretary-General, Rajya Sabha at Conferences (2002-2011)

FOR USE OF RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT ONLY lR;eso t;rs PARLIAMENTARY PRACTICES : SECRETARY-GENERAL, RAJYA SABHA AT CONFERENCES (2002-2011) DR. V.K. AGNIHOTRI SECRETARY-GENERAL RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI 2011 © RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT Price : ` 300/- C O N T E N T S PAGES PREFACE BY PARLIAMENTARY RULES AND PROCEDURES 1. Disclosure of Information from Register of Members’ Interests under the RTI Act, 2005 1-8 - Dr. V. K. Agnihotri 2. Disqualification of a Member of Rajya Sabha under Article 103 of the Constitution of India 9-14 - Dr. Yogendra Narain 3. Financial Control in Parliament 15-18 - Dr. Yogendra Narain 4. Government Legislation : From listing to President’s Assent 19-24 - Dr. V. K. Agnihotri 5. Impact of Dissolution of Lok Sabha (Lower House) on Legislative and Other Business 25-38 - Dr. V. K. Agnihotri 6. Implications of the Expulsion of a Member from His or Her Political Party 39-45 - Dr. V. K. Agnihotri 7. Issues concerning States/Provinces which can be taken up in Central Legislatures (Parliaments) 46-50 - Shri N. C. Joshi 8. Petitioning the Parliament 51-63 - Dr. V. K. Agnihotri 9. Privileges and Immunities in Parliament 64-68 - Dr. Yogendra Narain 10. Raising Matters of Urgent Public Importance : Zero Hour Submissions and Special Mention Procedures 69-70 - Dr. Yogendra Narain 11. Rules on the participation of Members of Parliament in proceedings in which they have a direct or indirect Financial Interest 71-82 - Dr. V. K. Agnihotri 12. Statements by Ministers on the Floor of the House 83-93 - Dr. V. -

Election As Speaker a New Beginning

XVIIth Lok Sabha in the service of the Nation The First Two Years The Parliament of a nation is a living embodiment of the faith of the people in a democratic polity and an affirmation of commitment to participation in the governance process. The Houses of Parliament are thus hallowed institutions that represent the sovereign will of the people and are mandated by the Constitution to guide the destiny of the nation. It is therefore critical that all efforts are made to provide Members with a congenial and enabling environment for their effective participation in the business of the Houses of Parliament and in the discharge of their roles as representatives of the people. Meaningful and effective participation of Members in the business of Lok Sabha is the cornerstone of strong and vibrant democracy, that is India. In furtherance of this cause, the Lok Sabha under the stewardship of Hon'ble Speaker, Shri Om Birla, has in the last two years, endeavored to provide all Members with the comfort and assurance of an enabling environment in the House that is conducive for free and fair debates and discussions as is cherishable in a parliamentary democracy. Under the guidance of Hon'ble Speaker, a series of steps have been taken for sensitive handling of all matters that may contribute to improvement in ease in participation for the Members in House proceedings. These measures include necessary facilitation to all members in terms of improved research support, proactive library services, welfare and housing, prompt medical assistance, etc. In addition, digital tools are being promoted to help bring greater efficiency and transparency in the functioning of the Lok Sabha. -

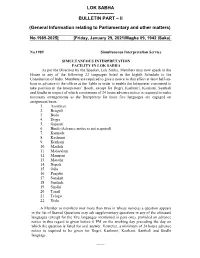

Lok Sabha ------Bulletin Part – Ii

LOK SABHA ----------------- BULLETIN PART – II (General Information relating to Parliamentary and other matters) No.1989-2025] [Friday, January 29, 2021/Magha 09, 1942 (Saka) No.1989 Simultaneous Interpretation Service SIMULTANEOUS INTERPRETATION FACILITY IN LOK SABHA As per the Direction by the Speaker, Lok Sabha, Members may now speak in the House in any of the following 22 languages listed in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India. Members are required to give a notice to that effect at least half-an- hour in advance to the officer at the Table in order to enable the Interpreter concerned to take position in the Interpreters’ Booth, except for Dogri, Kashmiri, Konkani, Santhali and Sindhi in respect of which a minimum of 24 hours advance notice is required to make necessary arrangements as the Interpreters for these five languages are engaged on assignment basis. 1. Assamese 2. Bengali 3. Bodo 4. Dogri 5. Gujarati 6. Hindi (Advance notice is not required) 7. Kannada 8. Kashmiri 9. Konkani 10. Maithili 11. Malayalam 12. Manipuri 13. Marathi 14. Nepali 15. Odia 16. Punjabi 17. Sanskrit 18. Santhali 19. Sindhi 20. Tamil 21. Telugu 22. Urdu A Member or members (not more than two) in whose name(s) a question appears in the list of Starred Questions may ask supplementary questions in any of the aforesaid languages (except for the five languages mentioned in para one), provided an advance notice in this regard is given before 6 PM on the working day preceding the day on which the question is listed for oral answer. However, a minimum of 24 hours advance notice is required to be given for Dogri, Kashmiri, Konkani, Santhali and Sindhi language.