Newfoundland and Labrador Primary Health Care Renewal Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thms Summary for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland And

THMs Summary for Public Water Supplies Water Resources Management Division in Newfoundland and Labrador Community Name Serviced Area Source Name THMs Average Average Total Samples Last Sample (μg/L) Type Collected Date Anchor Point Anchor Point Well Cove Brook 154.13 Running 72 Feb 25, 2020 Appleton Appleton (+Glenwood) Gander Lake (The 68.30 Running 74 Feb 03, 2020 Outflow) Aquaforte Aquaforte Davies Pond 326.50 Running 52 Feb 05, 2020 Arnold's Cove Arnold's Cove Steve's Pond (2 142.25 Running 106 Feb 27, 2020 Intakes) Avondale Avondale Lee's Pond 197.00 Running 51 Feb 18, 2020 Badger Badger Well Field, 2 wells on 5.20 Simple 21 Sep 27, 2018 standby Baie Verte Baie Verte Southern Arm Pond 108.53 Running 25 Feb 12, 2020 Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Pond 0.00 Simple 9 Dec 13, 2018 Barachois Brook Barachois Brook Drilled 0.00 Simple 8 Jun 21, 2019 Bartletts Harbour Bartletts Harbour Long Pond (same as 0.35 Simple 2 Jan 18, 2012 Castors River North) Bauline Bauline #1 Brook Path Well 94.80 Running 48 Mar 10, 2020 Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Sugarloaf Hill Pond 117.83 Running 68 Mar 03, 2020 Bay Roberts Bay Roberts, Rocky Pond 38.68 Running 83 Feb 11, 2020 Spaniard's Bay Bay St. George South Heatherton #1 Well Heatherton 8.35 Simple 7 Dec 03, 2013 (Home Hardware) Bay St. George South Jeffrey's #1 Well Jeffery's (Joe 0.00 Simple 5 Dec 03, 2013 Curnew) Bay St. George South Robinson's #1 Well Robinson's 3.30 Simple 4 Dec 03, 2013 (Louie MacDonald) Bay St. -

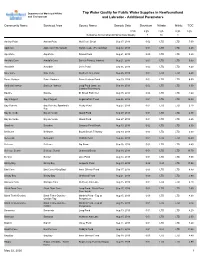

Tap Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland and Environment and Labrador - Additional Parameters

Department of Municipal Affairs Tap Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland and Environment and Labrador - Additional Parameters Community Name Serviced Area Source Name Sample Date Strontium Nitrate Nitrite TOC Units mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality 7 10 1 Anchor Point Anchor Point Well Cove Brook Sep 17, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 7.00 Appleton Appleton (+Glenwood) Gander Lake (The Outflow) Aug 12, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 6.40 Aquaforte Aquaforte Davies Pond Aug 21, 2019 0.00 LTD LTD 5.80 Arnold's Cove Arnold's Cove Steve's Pond (2 Intakes) Aug 21, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 5.00 Avondale Avondale Lee's Pond Sep 05, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 8.40 Baie Verte Baie Verte Southern Arm Pond Sep 26, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 6.40 Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Pond Aug 29, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 8.90 Bartletts Harbour Bartletts Harbour Long Pond (same as Sep 18, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 6.50 Castors River North) Bauline Bauline #1 Brook Path Well Aug 15, 2019 0.06 LTD LTD 4.60 Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Sugarloaf Hill Pond Sep 05, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 10.00 Bay Roberts Bay Roberts, Spaniard's Rocky Pond Aug 27, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 2.10 Bay Bay de Verde Bay de Verde Island Pond Sep 27, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 2.30 Bay de Verde Bay de Verde Island Pond Sep 27, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 2.60 Beaches Beaches Grassey Pond Brook Aug 13, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 6.50 Bellburns Bellburns Bound Brook Tributary Sep 30, 2019 0.05 LTD LTD 6.60 Belleoram Belleoram Rabbits Pond Sep 24, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 14.40 Bellevue Bellevue Big Pond Sep 16, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 4.40 Bellevue -

HYDROGEOLOGY 50°0' Central Newfoundland

55°15' 55°0' 54°45' 54°30' 54°15' 54°0' 53°45' 53°30' 53°15' 50°15' Department of Environment and Conservation Department of Natural Resources Map No. 3b HYDROGEOLOGY 50°0' Central Newfoundland Well Yield Well Depth 50°0' Characteristics Characteristics (m) Number (L/min) Hydrostratigraphic Unit Lithology of Wells Average Median Average Median Unit 1 schist, gneiss, Low to Moderate Yield 73 20 6 51 48 quartzite, slate Metamorphic Strata siltstone, Unit 2 conglomerate, argillite, Low to Moderate Yield 1403 20 7 51 46 greywacke, with Sedimentary Strata minor volcanic 49°45' flows and tuff Unit 3 basic pillow Low to Moderate Yield lava, flows, 723 22 9 50 46 Barr'D Islands Volcanic Strata breccia and tuff 49°45' Fogo Joe Batt's Arm Tilting Unit 4 mafic and ultramafic Shoal Bay Pike's Arm Low Yield intrusions of ophiolite 13 9 7 58 61 Herring Neck Change Islands complexes FogoC oIsolkasn Pdond Ophiolite Complexes Durrell Deep Bay Fogo Island Region Unit 5 granite, granodiorite, Salt Harbour N o r t h Twillingate Island Harbour diabase, and diorite 688 22 9 44 37 Little Harbour Cobbs Arm A t l a n t i c Low to Moderate Yield Too Good Arm Seldom intrusions Notre Dame Bay O c e a n Plutonic Strata Gilliards Cove F Jenkins Cove rid Keattyle Cove Black Duck Cove Little Seldom Tizzard's Harbour B Rogers Cove ay Indian Cove Surficial deposits - Unconsolidated sediments Stag Harbour Newville Valley Pond Moreton's Harbour Surficial Hydrostratigraphic Units Fairbanks-Hillgrade Unit A - Till Deposits Hillgrade Port Albert Well yields range from 2 litres per minute (L/min) to 136 L/min and averaged 29 L/min Bridgeport 49°30' Virgin Arm-Carter's Cove with a median value of 18 L/min. -

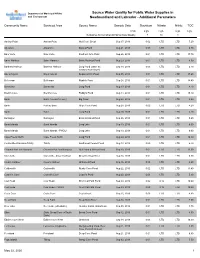

Source Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland And

Department of Municipal Affairs Source Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in and Environment Newfoundland and Labrador - Additional Parameters Community Name Serviced Area Source Name Sample Date Strontium Nitrate Nitrite TOC Units mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality 7 10 1 Anchor Point Anchor Point Well Cove Brook Sep 17, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 7.20 Aquaforte Aquaforte Davies Pond Aug 21, 2019 0.00 LTD LTD 6.30 Baie Verte Baie Verte Southern Arm Pond Sep 26, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 17.70 Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Pond Aug 29, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 9.50 Bartletts Harbour Bartletts Harbour Long Pond (same as Sep 18, 2019 0.03 LTD LTD 6.70 Castors River North) Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Sugarloaf Hill Pond Sep 05, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 17.60 Belleoram Belleoram Rabbits Pond Sep 24, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 14.40 Bonavista Bonavista Long Pond Aug 13, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.10 Brent's Cove Brent's Cove Paddy's Pond Aug 14, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 15.10 Burin Burin (+Lewin's Cove) Big Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.90 Burin Port au Bras Gripe Cove Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.02 LTD LTD 4.20 Burin Burin Long Pond Aug 28, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 4.10 Burlington Burlington Eastern Island Pond Sep 26, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 9.60 Burnt Islands Burnt Islands Long Lake Sep 10, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 6.00 Burnt Islands Burnt Islands - PWDU Long Lake Sep 10, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 6.00 Cape Freels North Cape Freels North Long Pond Aug 20, 2019 0.01 LTD LTD 10.30 Centreville-Wareham-Trinity Trinity Southwest Feeder Pond Aug 13, 2019 0.00 LTD LTD 6.70 Channel-Port -

Codes Used in the Newfoundland Commercial and Recreational Fisheries

Environment Canada Environnement Canada •• Fisheries Service des peches and Marine Service et des sciences de la mer 1 DFO ll ll i ~ ~~ll[lflll ~i~ 1 \11 1f1i! l1[1li eque 07003336 Codes Used in the Newfoundland Commercial and Recreational Fisheries by Don E. Waldron Data Record Series No. NEW/D-74-2 Resource Development Branch Newtoundland Region ) CODES USED IN THE NEWFOUNDLAND COMMERCIAL AND RECREATIONAL FISHERIES by D.E. Waldron Resource Development Branch Newfoundland Region Fisheries & Marine Service Department of the Environment St. John's, N'fld. February, 1974 GULF FlSHERIES LIBRARY FISHERIES & OCEANS gwt.IV HEOUE DES PECHES GOLFE' PECHES ET OCEANS ABSTRACT Data Processing is used by most agencies involved in monitoring the recreational and commercial fisheries of Newfoundland. There are three Branches of the Department of the Environment directly involved in Data Collection and Processing. The first two are the Inspection and the Conservation and Protection Branches (the collectors) and the Economics and Intelligence Branch (the processors)-is the third. To facilitate computer processing, an alpha-numeric coding system has been developed. There are many varieties of codes in use; however, only species, gear, ICNAF area codes, Economic and Intelligence Branch codes, and stream codes will be dealt with. Figures and Appendices are supplied to help describe these codes. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........... .. ... .... ... ........... ................ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv LIST .or FIGURES ....... .................................... v LIST OF TABLES ............................................ vi INTRODUCTION l Description of Data Coding .............. ~ .. .... ... 3 {A) Coding Varieties ••••••••••••••• 3 (I) Species Codes 3 ( II ) Gear Codes 3 (III) Area Codes 3 (i) ICNKF 4 (ii) Statistical Codes 7 (a) Statistical Areas 7 (b) Statistical Sections 7 (c) Community (Settlement) Codes 17 (iii) Comparison of ICNAF AND D.O.E. -

Operational Area of Ambulance Services

GOVERNMENT OF NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND COMMUNITY SERVICES Board Services POLICY: Operational Area of POLICY NUMBER: EHS 2003-09-28 Ambulance Services ORIGINAL DATE: January 22, 1998 LAST REVISED DATE: November 1, 2005 I. PURPOSE: A. To define the primary operational/service area for ambulance services. B. To define the secondary operational/service area for ambulance services. II. POLICY: A. The area outlined in the Motor Carrier Certificate issued by the Board of Commissioners of Public Utilities shall be recognized by the Department as the primary operational territory of the service named on the license. This area shall be broken down into base service areas for services that are funded for more then one base. B. Services are required to respond to emergency calls within their primary service area. C. Calls originating outside an operator’s primary service area shall be deferred to the operator licensed for that area. If an operator cannot respond to a call within their service area then the next closest operator shall be contacted to perform the transport. D. As a secondary operational area operators have the right to respond to calls between any two points in the Province, upon the request of a medical doctor, registered nurse, or police officer and such calls shall only be honored for payment if transports are performed in accordance with all Departmental requirements including the policies applicable to outside service area authorizations. E. A call into the secondary operational area shall only be performed providing the primary operator for that service area cannot perform the transport and the secondary operator being requested is the next closest available operator to the incident who can perform the call in accordance with all Departmental requirements. -

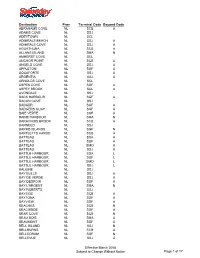

Destination Prov Terminal Code Beyond Code ABRAHAMS COVE

Destination Prov Terminal Code Beyond Code ABRAHAMS COVE NL SCB A ADAMS COVE NL SSJ ADEYTOWN NL SCL ADMIRALS BEACH NL SSJ A ADMIRALS COVE NL SSJ A AGUATHUNA NL SCB A ALLANS ISLAND NL SMA N AMHERST COVE NL SCL ANCHOR POINT NL SCB A ANGELS COVE NL SSJ A APPLETON NL SGF A AQUAFORTE NL SSJ A ARGENTIA NL SSJ A ARNOLDS COVE NL SCL ASPEN COVE NL SGF A ASPEY BROOK NL SCL A AVONDALE NL SSJ BACK HARBOUR NL SGF A BACON COVE NL SSJ BADGER NL SGF A BADGERS QUAY NL SGF A BAIE VERTE NL SGF A BAINE HARBOUR NL SMA N BARACHOIS BROOK NL SCB A BARNEED NL SSJ BARRD ISLANDS NL SGF N BARTLETTS HARBO NL SCB A BATTEAU NL SDA A BATTEAU NL SGF A BATTEAU NL SMO A BATTEAU NL SSJ A BATTLE HARBOUR NL SDA L BATTLE HARBOUR NL SGF L BATTLE HARBOUR NL SMO L BATTLE HARBOUR NL SSJ L BAULINE NL SSJ BAY BULLS NL SSJ A BAY DE VERDE NL SSJ A BAY DESPOIR NL SGF A BAY L'ARGENT NL SMA N BAY ROBERTS NL SSJ BAYSIDE NL SCB A BAYTONA NL SGF A BAYVIEW NL SGF A BEACHES NL SCB N BEACHSIDE NL SGF A BEAR COVE NL SCB N BEAU BOIS NL SMA A BEAUMONT NL SGF A BELL ISLAND NL SSJ N BELLBURNS NL SCB A BELLEORAM NL SGF N BELLEVUE NL SSJ A Effective March 2008 Subject to Change Without Notice Page 1 of 17 Destination Prov Terminal Code Beyond Code BELLMANS COVE NL SCB A BENOITS COVE NL SCB A BENTON NL SGF A BIDE ARM NL SCB N BIG BROOK NL SAN N BIRCHY BAY NL SGF A BIRCHY COVE BB NL SCL BIRCHY HEAD NL SCB N BIRD COVE NL SCB A BISCAY BAY NL SSJ BISHOPS COVE NL SSJ BISHOPS FALLS NL SGF BLACK DUCK NL SCB A BLACK DUCK COVE NL SCB A BLACK DUCK SIDI NL SCB A BLACK TICKLE NL SDA L BLACK TICKLE NL SGF L BLACK -

Tap Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland and Labrador and Environment Physical Parameters and Major Ions

Department of Municipal Affairs Tap Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland and Labrador and Environment Physical Parameters and Major Ions Serviced Area(s) Source Name Sample Date Alkalinity Colour Conductivity Hardness pH TDS TSS Turbidity Boron Bromide Calcium Chloride Fluoride Potassium Sodium Sulphate Units mg/L TCU µS/cm mg/L mg/L mg/L NTU mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L 15 6.5 - 8.5 500 1.0 5.0 250 1.5 200 500 Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality Aesthetic (A) or Contaminant (C) Parameter A A A C C A C A A Anchor Point Anchor Point Well Cove Brook Sep 17, 2019 106.00 10 243.0 120.00 8.28 158 0.60 LTD LTD 25.00 13 LTD LTD 7 1 Appleton Appleton (+Glenwood) Gander Lake (The Outflow) Aug 12, 2019 LTD 26 33.0 2.00 5.16 21 0.60 LTD LTD 1.00 7 LTD LTD LTD 1 Aquaforte Aquaforte Davies Pond Aug 21, 2019 12.00 14 107.0 LTD 7.79 70 0.40 LTD LTD LTD 24 LTD LTD 14 2 Arnold's Cove Arnold's Cove Steve's Pond (2 Intakes) Aug 21, 2019 12.00 10 61.0 5.00 7.21 40 0.60 LTD LTD 2.00 13 LTD LTD 9 1 Avondale Avondale Lee's Pond Sep 05, 2019 14.00 2 88.0 12.00 8.25 57 0.40 LTD LTD 5.00 15 LTD LTD 11 1 Baie Verte Baie Verte Southern Arm Pond Sep 26, 2019 LTD 19 34.0 5.00 5.05 22 0.20 LTD LTD 2.00 7 LTD LTD 2 1 Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Pond Aug 29, 2019 8.00 83 38.0 5.00 7.33 25 0.40 LTD LTD 2.00 4 LTD LTD 4 2 Bartletts Harbour Bartletts Harbour Long Pond (same as Castors Sep 18, 2019 96.00 23 265.0 112.00 8.42 172 0.50 LTD LTD 25.00 22 LTD LTD 12 3 River North) Bauline Bauline #1 Brook Path Well Aug 15, -

Sorted by Zone Municipality 1 Bauline 1 Bay Bulls 1 Biscayan Cove 1

Sorted by Zone Municipality 1 Bauline 1 Bay Bulls 1 Biscayan Cove 1 Chamberlains 1 Conception Bay South 1 Flatrock 1 Foxtrap 1 Goulds 1 Hogan’s Pond 1 Holyrood 1 Kelligrews 1 Lawrence Pond 1 Logy Bay 1 Maddox Cove 1 Manuels 1 Middle Cove 1 Mount Pearl 1 Outer Cove 1 Paradise (Avalon Pen) 1 Petty Harbour 1 Portugal Cove 1 Pouch Cove 1 Quidi Vidi 1 St. John’s 1 St. Phillip’s 1 Salt Harbour Island 1 Seal Cove (Avalon Pen) 1 Shoe Cove (Avalon Pen) 1 Torbay 1 Upper Gullies 1 Wedgewood Park 1A Bell Island 1A Lance Cove 1A Wabana 2 Admiral’s Beach 2 Admiral’s Cove 2 Aquaforte 2 Bauline East 2 Biscay Bay 2 Brigus Junction 2 Brigus South 2 Burnt Cove 2 Calvert 2 Cape Broyle 2 Cape Race 2 Cappahayden 2 Colinet 2 Fermeuse 2 Ferryland 2 Forest Field 2 Gaskiers 2 Gulch 2 Harricott 2 Kingman’s 2 La Manche (Avalon Pen) 2 Long Beach (Trepassey-Av Pen) 2 Mahers 2 Mall Bay 2 Markland 2 Mitchells Brook 2 Mobile 2 Mount Carmel 2 New Bridge 2 O’Donnells 2 Path End 2 Peter’s River 2 Point La Haye 2 Port Kirwan 2 Portugal Cove South 2 Renews 2 River Head (St. Mary’s Area) 2 St. Catherine’s 2 St. Joseph’s (Avalon Pen) 2 St. Mary’s 2 St. Shotts 2 St. Stephens 2 St. Vincent’s 2 Salmonier 2 Tors Cove 2 Trepassey 2 Witless Bay 3 Adams Cove 3 Avondale 3 Bacon Cove 3 Bareneed 3 Bay de Verde 3 Bay Roberts 3 Bishop’s Cove 3 Blackhead (Con Bay North) 3 Blow Me Down 3 Brigus 3 Bristol’s Hope 3 Broad Cove 3 Brownsdale 3 Bryants Cove 3 Butlerville 3 Caplin Cove (C Bay North) 3 Carbonear 3 Cavendish 3 Chapels Cove 3 Clarke’s Beach 3 Coley’s Point 3 Colliers 3 Conception Harbour -

JUN 6 200! Attention: Ms

Newfoundland Power ,nc. 55 Kenmount Road POWER PO Box 8910 A FORTIS COMFANY St. John's, Newfoundland A1B3P6 HAND DELIVERED Business: (709) 737-5600 Facsimile: (709) 737-2974 June 6, 2001 vvvwv.newfbundlandpower.com Board of Commissioners of Public Utilities P.O. Box 21040 80- J u, v 120 Torbay Road St. John's, NF A1A 5B2 JUN 6 200! Attention: Ms. Cheryl Blundon Board Secretary . JOHN'S Ladies & Gentlemen: Re: Newfoundland Power Inc's ("the Applicant") Application to acquire the Support Structures of Aliant Telecom Inc. located in the Applicant's service territory Enclosed please find 15 copies each of the Applicant's Responses to Information Requests NLH 10.0 through 13.0. In addition, we have enclosed 15 copies of the Response to Information Request NLH 8.0 (1st Revision). The revision was necessary to correct a mistaken reference to another Response in the last paragraph of the original version. For convenience we have provided the Responses on 3 hole punched paper. We trust the enclosed are found to be in order. Yours very truly, Peter Alteen Corporate Counsel and Secretary Enclosure c. Mr. Wayne D. Chamberlain Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro Mr. Glen D. Belbin Hey wood, Kennedy, Belbin Telephone: (709) 737-5859 Website: http://www.newfoundlandpower.com Fax: (709) 737-2974 Email: palteen @ newfoundlandpower. com Newfoundland Power Inc. 55 Kenmount Road POWER PO Box 8910 A FORTIS COMPANY St. John's, Newfoundland A1B3P6 HAND DELIVERED Business: (709) 737-5600 Facsimile: (709) 737-2974 www.newfoundlandpower.com June 5, 2001 Board of Commissioners of Public Utilities P.O. -

My Be Xeroxed

CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL F 10 PAGES ONLY M Y BE XEROXED National Library Biblioth~e nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Canadian Theses Service Service des tMses canadiennes Ottawa. Canada K1AON4 NOTICE AVIS The quality of this microform is heavily dependent upon the La qualM de cette rnicroforme d~pend grandement de Ia quality of the original thJsis submitted for microfilming. qualit~ de Ia tMse soumise au microfilmage. Nous avons Every effort has been made to ensure the highest quality of tout fait pour assurer une qualit4 sup4rieure de reproduc· reproduction possible. lion. I~ pages are missing, contact the university which granted S'il m.mque des pages, veuillez communiquer avec the degree. l'universit6 qui a conf~r~ le grade. Some pages may have indistinct print especially if the La qualit6 d'impression de certaines pages peut lais!:P.r !I original pages were typed with a poor typewriter ribbon or d~sirer, surtout si les pages originates ont ~16 daclylogra if the university sent us an inferior photocopy. phi~es l raide d'un ruban us6 ou si runiversit~ nous a tart parvenir une photocopie de qualit6 inf6rieure. Reproduction ir. full or in part of this microform is governed La reproduction, ~me partielfe, de cette microtonne esl by the Canadian Copyright Act, R.S.C. 1970, c. C-30, and sou mise l Ia Loi canadienne sur le droit d'auteur. SAC subsequent amendments. 1970, c. C-30, et ses arnendements subs6quents. ~ · ... Cana d a I - . ' - . National library 1+1 of Canada The author has granted an irrevocable non· L'auteur a acc::orde une licence irrlwocable et exclusive licence slowing the National utxary non exclusive pennettant a Ia Bibliotheque of Canada to reproduce, loan, distribute or sel nationale du Canada de reproduire, prAter, copies of his/her thesis by any means and in distribuer ou vendre des copies de sa these any fonn or format, making this thesis avalable de quelque mani4~n~ et sous quelque forme to interested persons. -

30Th Annual Southcott Award Edition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Memorial University Newfoundland Digital Archive Initiative A quarterly publication of the Newfoundland Historic Trust 30th Annual Southcott Award Edition The Trust announced the recipients of the 30th Annual Southcott Awards on Tuesday, June 24 during a ceremony emceed by CBC’s Jon- athan Crowe. The event was held at the LSPU Hall in St. John’s, itself a former Southcott winner. Awards were presented in two categories: Building Restoration/Preservation and Heritage Tradesperson. The Southcott Award program was established by The Trust in 1984 to recognize excellence in the preservation and adaptive reuse of the architectural heritage of Newfoundland and Labrador. The overall goal of the program is to recognize and commend those who have demonstrated excellence in building design, restoration and preserva- tion. Four awards were presented in the Building Restoration/Preservation category to Anderson House in St. John’s, owned by Hubert Alacoque; Evelyn’s Place in Herring Neck, Notre Dame Bay, owned by The Old Salt Box Co.; the Hickey Family Homestead in Outer Cove, owned by Paul D. Hickey; and, the Lilly Building in downtown St. John’s, owned by Choices for Youth. Aiden Duff of St. John’s accepted the Heritage Tradesperson honour. The Southcott Award for Building Restoration/Preservation is presented to finished architectural restoration projects. The Heritage Tradeperson Award celebrates the skill and contribution of an individual in the craft or trade professions in heritage conservation. In order to be considered for this award, the individual must use specialist and traditional methods and also exhibit a high standard of craftsmanship.