Transforming Urban Neighbourhoods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cost of Privacy: Welfare Effects of the Disclosure of COVID-19 Cases

The Cost of Privacy: Welfare Effects of the Disclosure of COVID-19 Cases David Argente Chang-Tai Hsieh Munseob Lee Penn State University of Chicago UC San Diego July 2021 CEMLA-FRBNY-ECB South Korea’s Case Disclosure of detailed information of confirmed cases. Text messages, official websites, mobile apps. Targeted social distancing: avoid places where transmission risk is high Self-selection into changing commuting: own cost-benefit analysis, exploit heterogeneity in the benefits and costs of social distancing. Reduce the transmission of virus and the costs of social isolation. 1/16 Public Disclosure: Official Website Korean, male, born in 1987, living in Jungnang district. Confirmed on January 30. Hospitalized in Seoul Medical Center. January 24 Return trip from Wuhan without symptoms. January 26 Merchandise store* at Seongbuk district at 11 am, fortune teller* at Seongdong district by subway at 12 pm, massage spa* by subway in the afternoon, two convenience stores* and two supermarkets*. January 27 Restaurant* and two supermarkets* in the afternoon. January 28 Hair salon* in Seongbuk district, supermarket* and restaurant* in Jungnang district by bus, wedding shop* in Gangnam district by subway, home by subway. January 29 Tested at a hospital in Jungnang district. January 30 Confirmed and hospitalized. Note: The* denotes establishments whose exact names have been disclosed. 2/16 Public Disclosure: Mobile App - February 24, 2020 3/16 This Paper This paper: quantify the effect of public disclosure on the transmission of the virus and economic losses in Seoul. Use detailed mobile phone data to document the change in the flows of people across neighborhoods in Seoul in response to information. -

SOUTH KOREA – November 2020

SOUTH KOREA – November 2020 CONTENTS PROPERTY OWNERS GET BIG TAX SHOCK ............................................................................................................................. 1 GOV'T DAMPER ON FLAT PRICES KEEPS PUSHING THEM UP ...................................................................................................... 3 ______________________________________________________________________________ Property owners get big tax shock A 66-year-old man who lives in Mok-dong of Yangcheon District, western Seoul, was shocked recently after checking his comprehensive real estate tax bill. It was up sevenfold.He owns two apartments including his current residence. They were purchased using severance pay, with rent from the second unit to be used for living expenses. Last year, the bill was 100,000 won ($90) for comprehensive real estate tax. This year, it was 700,000 won. Next year, it will be about 1.5 million won. “Some people might say the amount is so little for me as a person who owns two apartments. However, I’m really confused now receiving the bill when I’m not earning any money at the moment,” Park said. “I want to sell one, but then I'll be obliged to pay a large amount of capital gains tax, and I would lose a way to make a living.” On Nov. 20, the National Tax Service started sending this year’s comprehensive real estate tax bills to homeowners. The homeowners can check the bills right away online, or they will receive the bills in the mail around Nov. 26. The comprehensive real estate tax is a national tax targeting expensive residential real estate and some kinds of land. It is separate from property taxes levied by local governments. Under the government’s comprehensive real estate tax regulation, the tax is levied yearly on June 1 on apartment whose government-assessed value exceeds 900 million won. -

The Impact of Economic Regulation on Retail Sector: Regulation of Business Hours of Large Discount Stores in South Korea

The Impact of Economic Regulation on Retail Sector: Regulation of Business Hours of Large Discount Stores in South Korea Kwangho Jung* and Sooki Lee** Abstract: Recently the large discount retailers (LDRs) including large discount chains (e.g., Emart, Homeplus, and Lotte Mart) and super supermarkets (SSMs) have been at the center of disputes in the retail industries in Korea. The 2012 Distribution Industry Development Act has allowed the head of a city or county to regulate the business hours between large mega-retailers and small and family-run stores in the neighborhood. The regulation of the business hours of the large discount retailers may have heterogeneous effects on their sales depending on various contexts of the market situation. The reduction of the business hours assumes a significant negative effect on the amount of sales of LDRs. However, the degree of reduction may significantly differ from how the LDRs respond to the regulation. The reduction of sales of LDRs is natural if LDRs affected by the regulation do not make any effort to promote sales. On the other hand, if LDRs try to maintain their sales with various marketing strategies and resources, their sales may not decrease and even relatively increase compared to the size of the sales for LDRs that are not affected by the regulation. In addition, although the regulation of the business hours for LDRs can reduce operating hours, their sales may increase due to an increase of market demand in some growing places. For instance, the sales in LDRs located at the market place where new large housings and apartments have been growing may increase. -

Fertility and the Proportion of Newlyweds in Different Municipalities

Fertility and the Proportion of Newlyweds in Different Municipalities Sang-Lim Lee Research Fellow, KIHASA Ji-Hye Lee Senior Researcher, KIHASA Introduction With the expansion in recent years of policies on low fertility and the rising concern over the potential risk of so-called “local population extinction”, inter-municipal differentials in fertility have become a subject of increasing social interest. However, the heightened interest in local-level fertility usually stops short at media-led comparisons of total fertility rates in ranking order. Comparisons of such nature seem inappropriate at best, as both the structure and dynamics of population vary across municipalities. Also, there has been a form of pervasive reductionism by which the high fertility rates of some municipalities are attributed to local government’s policy support. We attempt in this study to examine the relationship between fertility and the proportion of newlyweds in different areas. The characteristics of births to newlyweds More than 80 percent of births in Korea were attributed to couples in their first 5 years of marriage. This has been the case for more than 15 years. Almost all births to women in their late 20s were to women married 5 years or less. In women in their early 30s, a major childbearing- age group, the proportion of births to those married less than 5 years has been on the rise, as age at marriage has increased. The exceptionally high rate of births to newly married couples is traceable to the fact that most (90.3 percent) of births occurring in Korea are of first or second children (Birth Statistics for 2015, Statistics Korea). -

Republic of KOREA

Republic of KOREA Andong City, Republic of Korea Busanjin-gu, Busan Metropolitan City, Republic of Korea Changwon City, Republic of Korea Dangjin City, Republic of Korea Dobong-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea Gangdong-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea Goryeong-gun, Republic of Korea Gunsan City, Jeollabuk-do, Republic of Korea Guro-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea Gyeongsan City, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea Hwaseong City, Republic of Korea Incheon Metropolitan City, Republic of Korea Jincheon County, Republic of Korea Jung-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea Pohang City, Republic of Korea Sejong Special Self-Governing City, Republic of Korea Seongdong-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea Siheung City, Republic of Korea Suwon City, Republic of Korea Wonju City, Republic of Korea Yangcheon-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea Yangsan City, Gyeongsangnam-Do, Republic of Korea Yongin City, Republic of Korea Yongsan-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea Yuseong District, Daejeon Metropolitan City, Republic of Korea Healthy City Research Center, Institute of Health and Welfare, Yonsei University Andong City, Republic of Korea 1 - Population:167,743 People (2014) - Number of households:70,598 Andong City Households (2014) - Area:1,521.87 km2 (2014) andong mayor : Gwon Youngse http://www.andong.go.kr Industry Establishments Workers Wholesale and retail trade 3,372(27.8) 8,139(19.0) Hotels and restaurants 2,601(21.4) 5,787(13.5) Other community, repair and personal service activities 1,671(13.8) 3,012(7.0) Transport 1,162(9.6) 2,232(5.2) Manufacturing 851(7.0) 3,568(8.3) Education -

Korea Matters for America

KOREA MATTERS FOR AMERICA KoreaMattersforAmerica.org KOREA MATTERS FOR AMERICA FOR MATTERS KOREA The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through cooperative study, research, and dialogue. Established by the US Congress in 1960, the Center serves as a resource for information and analysis on critical issues of common concern, bringing people together to exchange views, build expertise, and develop policy options. Korea Matters for America Korea Matters for America is part of the Asia Matters for America initiative and is coordinated by the East-West Center in Washington. KoreaMattersforAmerica.org For more information, please contact: part of the AsiaMattersforAmerica.org initiative Asia Matters for America East-West Center in Washington PROJECT TEAM 1819 L Street, NW, Suite 600 Director: Satu P. Limaye, Ph.D. Washington, DC 20036 Coordinator: Aaron Siirila USA Research & Assistance: Ray Hervandi and Emma Freeman [email protected] The East-West Center headquarters is in Honolulu, Hawai‘i and can be contacted at: East-West Center 1601 East-West Road Honolulu, HI 96848 USA EastWestCenter.org Copyright © 2011 The East-West Center 1 2AMERICA FOR MATTERS KOREA AND ROK US INDICATOR, 2009 UNITED STATES SOUTH KOREA The United States and South Korea Population, total 307 million 48.7 million in Profile GDP (current $) $14,120 billion $833 billion The United States and South Korea are leaders in the world. The US economy is the world’s largest, while South Korea’s is the fifteenth larg- IN P GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) $45,989 $27,168 est. -

PDF Download

Investigative research towards the designation of shamanic village rituals as ‘intangible cultural properties’ of the Seoul Metropolitan Government Yang Jongsung Investigative research towards the designation of shamanic village rituals as ‘intangible cultural properties’ of the Seoul Metropolitan Government Yang Jongsung Senior Curator, the National Folk Museum of Korea ABSTRACT Shamanic rituals taking place in Aegissidang, Mount Bonghwa Dodang, and Bamseom Bugundang, were thoroughly investigated by three experts appointed by the Board of Cultural Properties of Seoul Metropolitan Government. This religious belief and its related practices is still carried on by many shamans, religious specialists and their followers with the doctrines being handed down orally rather than in the form of written scriptures. Nonetheless, it is still a struggle to convince many Koreans of the cultural worth of shamanism. Owing to a deeply ingrained and stereotypical definition of what constitute religious doctrines and practices, its value as cultural heritage is often rejected. The Seoul Metropolitan Government and its Board have taken the initiative in designating these rites as ‘intangible cultural properties’ and hope this will lead to a more positive understanding of shamanism as a significant and valuable part of Korean traditional culture. Introduction In South Korea, Seoul Metropolitan Government’s In this rapidly changing world, all countries wishing to designation system for intangible cultural property has maintain their own national culture must be seriously been operated in accordance with the municipal rules for concerned about the preservation of their intangible the protection of cultural property. Individuals, or groups heritage. The methods of preserving and protecting with exclusive talents or skills in specific heritage fields, intangible heritage are therefore now considered to be of submit an application form to the Cultural Property critical importance, with many cultural policy makers and Committee of Seoul Metropolitan Government. -

A Study of Perceptions of How to Organize Local Government Multi-Lateral Cross- Boundary Collaboration

Title Page A Study of Perceptions of How to Organize Local Government Multi-Lateral Cross- Boundary Collaboration by Min Han Kim B.A. in Economics, Korea University, 2010 Master of Public Administration, Seoul National University, 2014 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2021 Committee Membership Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH GRADUATE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS This dissertation was presented by Min Han Kim It was defended on February 2, 2021 and approved by George W. Dougherty, Jr., Assistant Professor, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs William N. Dunn, Professor, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs Tobin Im, Professor, Graduate School of Public Administration, Seoul National University Dissertation Advisor: B. Guy Peters, Maurice Falk Professor of American Government, Department of Political Science ii Copyright © by Min Han Kim 2021 iii Abstract A Study of Perceptions of How to Organize Local Government Multi-Lateral Cross- Boundary Collaboration Min Han Kim University of Pittsburgh, 2021 This dissertation research is a study of subjectivity. That is, the purpose of this dissertation research is to better understand how South Korean local government officials perceive the current practice, future prospects, and potential avenues for development of multi-lateral cross-boundary collaboration among the governments that they work for. To this purpose, I first conduct literature review on cross-boundary intergovernmental organizations, both in the United States and in other countries. Then, I conduct literature review on regional intergovernmental organizations (RIGOs). -

The Cost of Privacy: Welfare Effects of the Disclosure of COVID-19 Cases

The Cost of Privacy: Welfare Effects of the Disclosure of COVID-19 Cases∗ David Argente† Chang-Tai Hsieh‡ Pennsylvania State University University of Chicago Munseob Lee§ University of California San Diego May 2020 Abstract South Korea publicly disclosed detailed location information of individuals that tested positive for COVID-19. We quantify the effect of public disclosure on the transmission of the virus and economic losses in Seoul. We use detailed foot-traffic data from South Korea's largest mobile phone company to document the change in the flows of people across neighborhoods in Seoul in response to information on the locations of positive cases. We analyze the effect of the change in commuting flows in a SIR meta-population model where the virus spreads due to these flows. We endogenize these flows in a model of urban neighborhoods where individuals commute across neighborhoods to access jobs and leisure opportunities. Relative to a scenario where no information is disclosed, the change in commuting patterns due to public disclosure lowers the number of cases by 400 thousand and the number of deaths by 13 thousand in Seoul over two years. Compared to a city-wide lock-down that results in the same number of cases over two years, the economic cost is 50% lower with full disclosure. ∗We want to thank Fernando Alvarez, Jingting Fan, David Lagakos, Marc-Andreas Muendler, Valerie A. Ramey, and Nick Tsivanidis for their comments and suggestions and seminar participants at UC San Diego, FGV, and Insper. †Email: [email protected]. Address: 403 Kern Building, University Park, PA 16801. -

The Removal Efficiencies of Several Temperate Tree Species At

Article The Removal Efficiencies of Several Temperate Tree Species at Adsorbing Airborne Particulate Matter in Urban Forests and Roadsides Myeong Ja Kwak 1 , Jongkyu Lee 1, Handong Kim 1, Sanghee Park 1, Yeaji Lim 1, Ji Eun Kim 1, Saeng Geul Baek 2, Se Myeong Seo 3, Kyeong Nam Kim 3 and Su Young Woo 1,* 1 Department of Environmental Horticulture, University of Seoul, Seoul 02504, Korea; [email protected] (M.J.K.); [email protected] (J.L.); [email protected] (H.K.); [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (Y.L.); [email protected] (J.E.K.) 2 National Baekdudaegan Arboretum, Bonghwa 36209, Korea; [email protected] 3 Korea Forestry Promotion Institute, Seoul 07570, Korea; [email protected] (S.M.S.); [email protected] (K.N.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-10-3802-5242 Received: 22 August 2019; Accepted: 25 October 2019; Published: 30 October 2019 Abstract: Although urban trees are proposed as comparatively economical and eco-efficient biofilters for treating atmospheric particulate matter (PM) by the temporary capture and retention of PM particles, the PM removal effect and its main mechanism still remain largely uncertain. Thus, an understanding of the removal efficiencies of individual leaves that adsorb and retain airborne PM, particularly in the sustainable planning of multifunctional green infrastructure, should be preceded by an assessment of the leaf microstructures of widespread species in urban forests. We determined the differences between trees in regard to their ability to adsorb PM based on the unique leaf microstructures and leaf area index (LAI) reflecting their overall ability by upscaling from leaf scale to canopy scale. -

List of Districts of South Korea

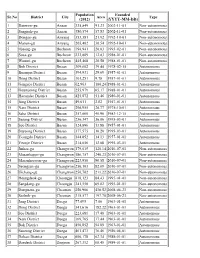

Population Founded Sr.No District City Area Type (2012) (YYYY-MM-DD) 1 Danwon-gu Ansan 335,849 91.23 2002-11-01 Non-autonomous 2 Sangnok-gu Ansan 380,574 57.83 2002-11-01 Non-autonomous 3 Dongan-gu Anyang 353,381 21.92 1992-10-01 Non-autonomous 4 Manan-gu Anyang 265,462 36.54 1992-10-01 Non-autonomous 5 Ojeong-gu Bucheon 194,941 20.03 1993-02-01 Non-autonomous 6 Sosa-gu Bucheon 232,809 12.83 1988-01-01 Non-autonomous 7 Wonmi-gu Bucheon 445,468 20.58 1988-01-01 Non-autonomous 8 Buk District Busan 309,602 39.44 1978-02-15 Autonomous 9 Busanjin District Busan 394,931 29.69 1957-01-01 Autonomous 10 Dong District Busan 101,251 9.78 1957-01-01 Autonomous 11 Gangseo District Busan 62,963 180.24 1988-01-01 Autonomous 12 Geumjeong District Busan 255,979 65.17 1988-01-01 Autonomous 13 Haeundae District Busan 425,872 51.46 1980-01-01 Autonomous 14 Jung District Busan 49,011 2.82 1957-01-01 Autonomous 15 Nam District Busan 296,955 26.77 1975-10-01 Autonomous 16 Saha District Busan 357,060 40.96 1983-12-15 Autonomous 17 Sasang District Busan 256,347 36.06 1995-03-01 Autonomous 18 Seo District Busan 124,896 13.88 1957-01-01 Autonomous 19 Suyeong District Busan 177,575 10.20 1995-03-01 Autonomous 20 Yeongdo District Busan 144,852 14.13 1957-01-01 Autonomous 21 Yeonje District Busan 214,056 12.08 1995-03-01 Autonomous 22 Jinhae-gu Changwon 179,015 120.14 2010-07-01 Non-autonomous 23 Masanhappo-gu Changwon 186,757 240.23 2010-07-01 Non-autonomous 24 Masanhoewon-gu Changwon 223,956 90.58 2010-07-01 Non-autonomous 25 Seongsan-gu Changwon 250,103 82.09 2010-07-01 -

Analyzing the Success Factors of Best Practices in the Korean Social Economy

Analyzing the Success Factors of Best Practices in the Korean Social Economy 2019.11 " Analyzing the Success Factors of Best Practices in the Korean Social Economy Published on 29.11.2019 Published in KoSEA Published at 7,8F 157 Sujeong-ro, Sujeong-gu, Seongnam, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea Publisher In-sun Kim(president.KoSEA) Tel 031-697-7700 Fax 031-697-7889 Website http://www.socialenterprise.or.kr Designed by sangsangneomeo ※ Copyright(c)2019 by KoSEA. All Page contents cannot be Not for sale copied without permission. Research Institute Hanshin University R&DB Foundation Principal investigator Jongick Jang(Professor of Global Business Department, Hanshin University) Co-investigator Changho Oh(Professor of Department of Business Administration, Hanshin University) Hyun S. Shin(Professor of Division of Business Administration, Hanyang University) Research assistant Jungsoo Park(Graduate School for Soical Innovation Business, Hanshin University) Suyeon Lee(Graduate School for Soical Innovation Business, Hanshin University) Gyejin Choi(Graduate School for Soical Innovation Business, Hanshin University) Jeonghoon Kang(Graduate School of Business Administration, Hanyang University) Table of Contents Foreword 5 Ⅰ. iCOOP Consumer Cooperatives 9 iCOOP Consumer Cooperatives, Repeating Innovations through a Strong Network Organization Ⅱ. Ansung Health Welfare Social Cooperative 32 Ansung Health Welfare Social Cooperative, Realizing the Co-Production Model of Medical Services and Local Community Building Ⅲ. Social Cooperative Dounuri 51 Social Cooperative Dounuri, Creating Decent Jobs in Care Services Ⅳ. Happy Bridge Cooperative 67 Members of Happy Bridge Cooperative, Moving towards the Innovation from Wage Workers to Collaborative Worker Owners Ⅴ. BeautifulStore 84 Creating a beautiful world of sharing and recycling where everyone participates Ⅵ. Dasomi Foundation 103 Dasomi Foundation: Shifting the Paradigm of Care Services through Partnership and Innovation Ⅶ.