64 Blues Festival Guide 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Velkommen Til Sementblues 2017!

2 The 9th international sementblues festival • Kjøpsvik 20. - 23. july 2017 Velkommen til Sementblues 2017! Kjøpsvik Bluesklubb har gleden av å ønske deg velkommen til den 9. Sementblues- festivalen i Kjøpsvik. Vi skal gjøre alt vi kan for at du skal få en topp festivalopplev- else, og vi ser fram til å møtes i Kjøpsvik. Under årets festival vil det bli laget et eget markedsom- råde med salgsboder. Dette starter i kirken hvor årets festival kunstner Terje Skogekker holder til, og går ned til torgområdet. Her blir veien sperret for biltrafikk. Under årets festival vil matservering være mulig å på Kroa Di, Pompel og Pilt en nyåpnet kaffebar og Stetind hotell. Årets vikingpris vil bli delt ut i teltet på lørdag formiddag. Her vil også den lokale kultur og musikk skolen underholde. Årets festival inneholder 80% blues og en liten dose pop/rock. Torsdag 20. juni startet årets bluesfestival med kirkekon- sert. Artistene er Rita Engedalen, Margit Bakken og Lisa Lystam. Resten av årets konserter vil bli holdt på torget i teltet og Kroa Di. Kjøpsvik Bluesklubb ønsker med dette å takke musikere, frivillige, våre trofaste og arbeidsomme medlemmer og sist men ikke mins alle dere som kommer som gjester på Sement- bluesen. I lag får vi dette til å bli en kjempehappening i bluesens navn. Ta vare på hverandre og nyt musikken, atmosfæren, naturen og folket. Styret. Sementblues jobber for å fremme blues musikken og dens historie. Festivalen vil fra og med 2017 sette fokus på artister som har påvirket, utviklet og skapt seg et navn blant blueskjennere og blues fans. -

TINSLEY ELLIS - Around Memphis - Little Charlie Baty - Nine CD Reviews

Blues Music Online Weekly Edition TINSLEY ELLIS - Around Memphis - Little Charlie Baty - Nine CD Reviews BLUES MUSIC ONLINE - March 18, 2020 - Issue 6 Table Of Contents 6 TINSLEY ELLIS Enjoying The Ride By Marc Lipkin - Alligator Records 10 TINSLEY ELLIS Red Clay Soul Man Originally Published January 2017 By Grant Britt 14 LITTLE CHARLIE BATY In Memoriam By Art Tipaldi - Thomas Cullen III 16 AROUND MEMPHIS Pandemic Effects 18 CD REVIEWS By Various Writers 29 Blues Music Store CDs Onsale COVER PHOTOGRAPHY © MARILYN STRINGER TOC PHOTOGRAPHY © MARILYN STRINGER TOC PHOTOGRAPHY © MARILYN STRINGER Tinsley Ellis Enjoying The Ride By Marc Lipkin - Alligator Records ver since he first hit the road 40 years shuffles, and it all sounds great.” The Chicago ago, blues-rock guitar virtuoso, soulful Sun-Times says, “It’s hard to overstate the Evocalist and prolific songwriter Tinsley raw power of his music.” Ellis has grown his worldwide audience one Ellis considers his new album, Ice scorching performance at a time. Armed with Cream In Hell, the most raw-sounding, guitar- blazing, every-note-matters guitar skills and drenched album of his career. Recorded scores of instantly memorable original songs, in Nashville and produced by Ellis and his Ellis has traveled enough miles, he says, “to longtime co-producer Kevin McKendree get to the moon and back six times.” He’s (John Hiatt, Delbert McClinton), Ice Cream released 17 previous solo albums, and has In Hell is a cathartic blast of blues-rock earned his place at the top of the blues-rock power. Though inspired by all three Kings world. -

The Blues Dogs Band Has Been Helping Him Discover Wisconsin, So Be Sure to Welcome Him

.After over 40 years playing blues in bars, these guys got it down. Dues have been paid and paid again. The Chippewa Valley Blues Society presents Harvey Fields started playing drums as a boy at the Checkerboard Lounge in Chicago with his mentors, Howlin' Wolf and Muddy Waters. His Uncle, Lucky Evans was an alumnus of the Howlin' Wolf band and took Harvey all around the world, playin' blues and payin dues. Steve John Meyer, lead vocalist, guitarist and harp player, is a graduate of thousands of smoky nights. He's led the 'dream life'... jammin' blues in every bar in Minnesota and Wisconsin, then spending the night on the road, in an old beat up van, usually cold, and snowing. Steve started blowin harp in '68, playin on the lakeshore, in laundry rooms and culverts to find 'the sound.' One night he was jamming with some guys he just met in an old roadhouse down by Cedar Lake and the place was packed. At one point the hot, sweaty crowd just stopped dancing to watch, and he never looked back. He knew he'd finally found it. Dean Wolfson plays bass. He's been jammin' round the twin cities since the 70's. Dean also plays for folk June 16, 2009 rocker Geno LaFond. The Blues Dogs band has been helping him discover Wisconsin, so be sure to welcome him. Kenny Danielson, from LacDuFlambeau, native American blues guitarist, singer and "long time blues enthusiast" rounds out the quartet for the evening. The Blues Dogs Next Week Upcoming Schedule The Pumps The Pumps If you haven't been to one of their June 20th Barnacles on Mille Lacs shows, you're missing out on a trio of cool cats, all June27th Smalley’s in Stillwater veterans of the local and national scene - Tom Brill July 4th Brewski's in Balsam Lake on guitar and vocals, Buck Barrickman on bass and July 11th Noon at the Harbor Bar Blues Fest vocals and Frank Juodis on drums and vocals. -

Groundhogs Back Against the Wall Mp3, Flac, Wma

Groundhogs Back Against The Wall mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Blues Album: Back Against The Wall Country: UK Released: 1986 Style: Blues Rock, Hard Rock, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1812 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1985 mb WMA version RAR size: 1181 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 558 Other Formats: VOC AU XM MP2 WMA MP4 MP3 Tracklist 1 Back Against The Wall 2 No To Submission 3 Blue Boar Blues 4 Waiting In The Shadows 5 Ain't No Slaver 6 Stick To Your Guns 7 In The Meantime 8 54146 Credits Bass – Dave Anderson Drums, Percussion – Mick Jones Guitar, Vocals – Tony McPhee Written-By – Tony McPhee Notes Issued under license from Demi Monde Records Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 5 099882 8 10529 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Back Against The DMLP 1014 Groundhogs* Demi Monde DMLP 1014 UK 1986 Wall (LP, Album) Back Against The Plastic Head PHRO 12CD Groundhogs* Wall (CD, Album, PHRO 12CD UK 2008 Records RE) Back Against The The Magnum CDTB 111 Groundhogs* Wall (CD, Album, CDTB 111 UK 1994 Music Group RE) Back Against The Abstract ABT054CD The Groundhogs Wall (CD, Album, RE, ABT054CD Russia Unknown Sounds Unofficial) Back Against The Abstract ABT054CD The Groundhogs ABT054CD US Unknown Wall (CD, RE) Sounds Related Music albums to Back Against The Wall by Groundhogs Groundhogs - BBC Radio One Live In Concert Groundhogs - Hogwash Groundhogs - Thank Christ For The Bomb Lenn Hammond / Milton Blake - Time / Back Against The Wall Groundhogs - Split Various - Back Against The Wall (A Tribute To Pink Floyd) Billy Boy Arnold - Checkin' It Out Groundhogs - You Don't Love Me. -

Bob Corritore Bio

Bob Corritore Bio Bob Corritore is one of the most active and highly regarded blues harmonica players on the scene today. His style passionately carries forward the old school of playing that Corritore learned as a young man directly from many of original pioneers of Chicago Blues. His sympathetic, yet fiery harmonica playing is featured on over 25 releases to date, on labels such as HighTone, HMG, Blue Witch, Blind Pig, Earwig, Putumayo, Random Chance, and the VizzTone Label Group. Many of these acclaimed releases have been nominated for various Handy, Grammy, and Blues Music Awards. Bob is also widely recognized for his many roles in the blues, as band leader, club owner, record producer, radio show host, arts foundation founder, and occasional writer. His amazing website www.bobcorritore.com and his weekly e-newsletter reflect a life thoroughly invested in the blues. Born on September 27, 1956 in Chicago, Bob first heard Muddy Waters on the radio at age 12, an event which changed his life forever. Within a year, he was playing harmonica and collecting blues albums. He would see blues shows in his early teens, including attending a Muddy Waters performance at his high school gymnasium. He would cut his teeth sitting in with John Henry Davis on Maxwell Street until he was old enough to sneak into blues clubs. He hung around great harp players such as Big Walter Horton, Little Mack Simmons, Louis Myers, Junior Wells, Big John Wrencher, and Carey Bell, and received harmonica tips and encouragement from many of them. He would regularly see the Aces, Howlin' Wolf, Muddy Waters, Billy Boy Arnold, John Brim, Sunnyland Slim, Smokey Smothers, Eddie Taylor, and in many cases became personal friends with these blues veterans. -

Son Sealsseals 1942-2004

January/February 2005 Issue 272 Free 30th Anniversary Year www.jazz-blues.com SonSon SealsSeals 1942-2004 INSIDE... CD REVIEWS FROM THE VAULT January/February 2005 • Issue 272 Son Seals 1942-2004 The blues world lost another star Son’s 1973 debut recording, “The when W.C. Handy Award-winning and Published by Martin Wahl Son Seals Blues Band,” on the fledging Communications Grammy-nominated master Chicago Alligator Records label, established him bluesman Son Seals, 62, died Mon- as a blazing, original blues performer and Editor & Founder Bill Wahl day, December 20 in Chicago, IL of composer. Son’s audience base grew as comlications with diabetes. The criti- he toured extensively, playing colleges, Layout & Design Bill Wahl cally acclaimed, younger generation clubs and festivals throughout the coun- guitarist, vocalist and songwriter – try. The New York Times called him “the Operations Jim Martin credited with redefining Chicago blues most exciting young blues guitarist and Pilar Martin for a new audience in the 1970s – was singer in years.” His 1977 follow-up, Contributors known for his intense, razor-sharp gui- “Midnight Son,” received widespread ac- Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, tar work, gruff singing style and his claim from every major music publica- Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, charismatic stage presence. Accord- tion. Rolling Stone called it ~one of the David McPherson, Tim Murrett, ing to Guitar World, most significant blues Peanuts, Mark Smith, Duane “Seals carves guitar albums of the decade.” Verh and Ron Weinstock. licks like a chain On the strength of saw through solid “Midnight Son,” Seals Check out our new, updated web oak and sings like began touring Europe page. -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

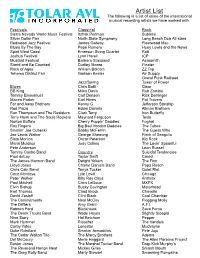

Artist List the Following Is a List of Some of the International Musical Recording Artists We Have Worked With

Artist List The following is a list of some of the international musical recording artists we have worked with. Festivals Classical Rock Sierra Nevada World Music Festival Itzhak Perlman Sublime Silver Dollar Fair North State Symphony Long Beach Dub All-stars Redwood Jazz Festival James Galway Fleetwood Mac Blues By The Bay Pepe Romero Huey Lewis and the News Spirit West Coast Emerson String Quartet Ratt Joshua Festival Lynn Harell ICP Mustard Festival Barbara Streisand Aerosmith Stand and Be Counted Dudley Moore Floater Rock of Ages William Bolcom ZZ Top Tehema District Fair Garison Keeler Air Supply Grand Funk Railroad Jazz/Swing Tower of Power Blues Chris Botti Gwar BB King Miles Davis Rob Zombie Tommy Emmanuel Carl Denson Rick Derringer Maceo Parker Earl Hines Pat Travers Far and Away Brothers Kenny G Jefferson Starship Rod Piaza Eddie Daniels Allman Brothers Ron Thompson and The Resistors Clark Terry Iron Butterfly Terry Hank and The Souls Rockers Maynard Ferguson Tesla Norton Buffalo Cherry Poppin’ Daddies Foghat Roy Rogers Big Bad Voodoo Daddies The Tubes Smokin’ Joe Cubecki Bobby McFerrin The Guess Who Joe Lewis Walker George Shearing Flock of Seagulls Sista Monica Oscar Peterson Kid Rock Maria Muldaur Judy Collins The Lovin’ Spoonful Pete Anderson Leon Russel Tommy Castro Band Country Suicidal Tendencies Paul deLay Taylor Swift Creed The James Harmon Band Dwight Yokem The Fixx Lloyd Jones Charlie Daniels Band Papa Roach Chris Cain Band Tanya Tucker Quiet Riot Coco Montoya Lyle Lovitt Chicago Peter Welker Billy Ray Cirus Anthrax Paul Mitchell Chris LeDoux MXPX Elvin Bishop Bucky Covington Motorhead Earl Thomas Chad Brock Chavelle David Zasloff Clint Black Coal Chamber The Commitments Neal McCoy Flogging Molly The Drifters Amy Grant A.F.I. -

In the Studio: the Role of Recording Techniques in Rock Music (2006)

21 In the Studio: The Role of Recording Techniques in Rock Music (2006) John Covach I want this record to be perfect. Meticulously perfect. Steely Dan-perfect. -Dave Grohl, commencing work on the Foo Fighters 2002 record One by One When we speak of popular music, we should speak not of songs but rather; of recordings, which are created in the studio by musicians, engineers and producers who aim not only to capture good performances, but more, to create aesthetic objects. (Zak 200 I, xvi-xvii) In this "interlude" Jon Covach, Professor of Music at the Eastman School of Music, provides a clear introduction to the basic elements of recorded sound: ambience, which includes reverb and echo; equalization; and stereo placement He also describes a particularly useful means of visualizing and analyzing recordings. The student might begin by becoming sensitive to the three dimensions of height (frequency range), width (stereo placement) and depth (ambience), and from there go on to con sider other special effects. One way to analyze the music, then, is to work backward from the final product, to listen carefully and imagine how it was created by the engineer and producer. To illustrate this process, Covach provides analyses .of two songs created by famous producers in different eras: Steely Dan's "Josie" and Phil Spector's "Da Doo Ron Ron:' Records, tapes, and CDs are central to the history of rock music, and since the mid 1990s, digital downloading and file sharing have also become significant factors in how music gets from the artists to listeners. Live performance is also important, and some groups-such as the Grateful Dead, the Allman Brothers Band, and more recently Phish and Widespread Panic-have been more oriented toward performances that change from night to night than with authoritative versions of tunes that are produced in a recording studio. -

BOB DYLAN 1966. Jan. 25. Columbia Recording Studios According to The

BOB DYLAN 1966. Jan. 25. Columbia Recording Studios According to the CD-2 “No Direction Home”, Michael Bloomfield plays the guitar intro and a solo later and Dylan plays the opening solo (his one and only recorded electric solo?) 1. “Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat” (6.24) (take 1) slow 2. “Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat” (3.58) Bloomfield solo 3. “Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat” (3.58) Dylan & Bloomfield guitar solo 4. “Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat” (6.23) extra verse On track (2) there is very fine playing from MB and no guitar solo from Uncle Bob, but a harmonica solo. 1966 3 – LP-2 “BLONDE ON BLONDE” COLUMBIA 1966? 3 – EP “BOB DYLAN” CBS EP 6345 (Portugal) 1987? 3 – CD “BLONDE ON BLONDE” CBS CDCBS 66012 (UK) 546 1992? 3 – CD “BOB DYLAN’S GREATEST HITS 2” COLUMBIA 471243 2 (AUT) 109 2005 1 – CD-2 “NO DIRECTION HOME – THE SOUNDTRACK” THE BOOTLEG SERIES VOL. 7 - COLUMBIA C2K 93937 (US) 529 Alternate take 1 2005 1 – CD-2 “NO DIRECTION HOME – THE SOUNDTRACK” THE BOOTLEG SERIES VOL. 7 – COL 520358-2 (UK) 562 Alternate take 1 ***** Febr. 4.-11, 1966 – The Paul Butterfield Blues Band at Whiskey a Go Go, LA, CA Feb. 25, 1966 – Butterfield Blues Band -- Fillmore ***** THE CHICAGO LOOP 1966 Prod. Bob Crewe and Al Kasha 1,3,4 - Al Kasha 2 Judy Novy, vocals, percussion - Bob Slawson, vocals, rhythm guitar - Barry Goldberg, organ, piano - Carmine Riale, bass - John Siomos, drums - Michael Bloomfield, guitar 1 - John Savanno, guitar, 2-4 1. "(When She Wants Good Lovin') She Comes To Me" (2.49) 1a. -

Luther Johnson – Telarc.Com Luther “Guitar Junior” Johnson Is One of the Premier Blues Artists to Emerge from Chicago's

Luther Johnson – telarc.com Luther “Guitar Junior” Johnson is one of the premier blues artists to emerge from Chicago’s music scene. Hailing from Itta Bena, Mississippi, Johnson arrived in Chicago in the mid-fifties a young man. At around the same time, the West Side guitar style, a way of playing alternating stinging single-note leads with powerful distorted chords, was being created mostly by Magic Sam and Otis Rush. Originally developed because their small bands could not afford both lead and rhythm guitar players, this style grew into an important contribution to modern blues and rock, influencing such notables as Eric Clapton and Mark Knopfler. Johnson served a long sideman apprenticeship with both Magic Sam and Muddy Waters, while developing into a strong performer in his own right. Today, Luther is widely considered the foremost proponent of the West Side guitar style and the heir apparent to the late Magic Sam’s West Side throne. Luther Johnson first gained an international reputation as a guitarist and vocalist with Muddy Waters’ band, touring the U.S., Europe, Japan and Australia from 1973-79. Given the opportunity to front the band on his featured tunes in each show, Johnson’s super-charged performances consistently thrilled audiences in the world’s leading concert halls, including Carnegie Hall, Kennedy Center and Radio City Music Hall as well as at music festivals in Newport, Antibes, New Orleans and countless others. During his association with Muddy Waters, Johnson also shared the stage with The Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton, The Allman Brothers and Johnny Winter. -

Jan. 24, 1970 – Mike Bloomfield & Nick Gravenites

Jan. 24, 1970 – Mike Bloomfield & Nick Gravenites – 750 Vallejo In North Beach, SF “The Jam” Mike Bloomfield and friends at Fillmore West - January 30-31-Feb. 1-2, 1970? Feb. 11, 1970 -- Fillmore West -- Benefit for Magic Sam featuring: Butterfield Blues Band / Mike Bloomfield & Friends / Elvin Bishop Group / Charlie Musselwhite / Nick Gravenites Feb. 28, 1970 – Mike Bloomfield, Keystone Korner, SF March 19, 1970 – Elvin Bishop Group plays Keystone Korner , SF Bloomfield was supposed to show for a jam. Did he? March 27,28, 1970 – Mike Bloomfield and Nick Gravenites, Keystone Korner ***** MICHAEL BLOOMFIELD AND FRIENDS 1970. Feb. 27. Eagles Auditorium, Seattle 1. “Wine” (8.00) This is the encore from Seattle added on the bootleg as a “filler”! The rest is from Long Beach Auditorium Apr. 8, 1971. 1970 1 – CDR “JAMES COTTON W/MIKE BLOOMFIELD AND FRIENDS” Bootleg 578 ***** JANIS JOPLIN AND THE BUTTERFIELD BLUES BAND 1970. Mar. 28. Columbia Studio D, Hollywood, CA Janis Joplin, vocals - Paul Butterfield, hca - Mike Bloomfield, guitar - Mark Naftalin, organ - Rod Hicks, bass - George Davidson, drums - Gene Dinwiddle, soprano sax, tenor sax - Trevor Lawrence, baritone sax - Steve Madaio, trumpet 1. “One Night Stand” (Version 1) (3.01) 2. “One Night Stand” (Version 2) wrong speed 1982 1 – LP “FAREWELL SONG” CBS 32793 (NL) 1992 1 – CD “FAREWELL SONG” COLUMBIA 484458 2 (US) ?? 2 – CD-3 BOX SET CBS ***** SAM LAY 1970 Producer Nick Gravenites (and Michael Bloomfield) Sam Lay, dr, vocals - Michael Bloomfield, guitar - Bob Jones, dr – bass ? – hca ? – piano ? – organ ? Probably all of The Butterfield Blues Band is playing. Mark Naftalin, Barry Goldberg, Paul Butterfield 1.