Entire Newsletter (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release Sunday

Press release 2019 FIA Formula One Socar Azerbaijan Grand Prix – Race – Sunday Weather: sunny and dry, 18-20°C air, 34-42°C track Azerbaijan - Un point ! Frédéric Vasseur, Team Principal Alfa Romeo Racing and CEO Sauber Motorsport AG: "As happy we’ve been after yesterday’s qualifying, the more disappointed we are after the race. One point I call damage limitation, but to be honest it could have been more. The bad news came this morning regarding Kimi’s front wing. It was a marginal error with the deflection - on Antonio’s car the same front wing with the same specification was fine – but the consequence was that we had to change the specification and Kimi had to start from the pit lane. And as surprisingly there was no safety car this time, we were stuck in traffic with both cars, and whilst both Kimi and Antonio did a good job, our race was compromised." Kimi Räikkönen (car number 7): Alfa Romeo Racing C38 (Chassis 02/Ferrari) Result: 10th. Start on soft tyres and after 8 laps change to medium tyres "Not an easy weekend for us. Wasn’t the plan to start from the pit lane but it is what it is, so one point is kind of the maximum we could achieve today. We pitted earlier to get out of the traffic but then I struggled for the whole race with switching the tyres on. Bit disappointed as I was expecting a lot more but I have the feeling that the next race will be easier for us." Antonio Giovinazzi (car number 99): Alfa Romeo Racing C38 (Chassis 03/Ferrari) Result: 12th. -

Press Release

Press release Alfa Romeo Sauber F1 Team installs 3rd MetalFAB1 system and extends technology partnership with Additive Industries 5-year Technology Partnership confirms ambition Sauber Engineering to become a leading industrial 3D metal printing supplier October 19, 2018 – Eindhoven (The Netherlands) / Hinwil (Switzerland) / Austin (Texas, USA) – At the start of the Formula 1 race event in Austin, Texas, Alfa Romeo Sauber F1 Team and Additive Industries have announced to extend their 3-year Technology Partnership to 5 years. Recently the Alfa Romeo Sauber F1 Team has taken delivery of its third MetalFAB1 system within a year and expanded its 2nd system with an additional build chamber or Additive Manufacturing Core to expand the productivity. Frédéric Vasseur, Team Principal Alfa Romeo Sauber F1 Team and CEO Sauber Motorsport AG said: “We are pleased to be extending our current partnership with Additive Industries, and to introduce a third MetalFAB1 3D printing system to our facilities. Not only do we aim to develop our production of parts for Formula One further, but we are also expanding our competences and activity in our third- party businesses. Building on the successful collaboration we have had so far, we look forward to working with Additive Industries and making further progress in our shared projects.” Christoph Hansen, Head of Technical Development at Sauber Engineering AG added: “After an in depth evaluation of all systems we found Additive Industries’ MetalFAB1 to be the only true industrial system available on the market. Their level of integration and automation allowed us to implement the technology very fast and with only a small team of experts. -

Alfa Romeo Sauber Partnership

Contact: Mike Ofiara Alfa Romeo and Sauber Motorsport Extend Partnership Alfa Romeo and Sauber Motorsport will continue to join forces at the highest level of motorsports with multi- year partnership extension July 14, 2021, Auburn Hills, Mich. - Alfa Romeo and Sauber Motorsport extend their partnership on a multi-year agreement. The renewal of this relationship represents an exciting new chapter in the long and prestigious motorsports history of two brands with an impressive racing heritage that includes success in Formula One, sports cars and touring cars. Formula One is the ultimate laboratory and therefore a vital test bed for Alfa Romeo on its path to electrification. In addition, it is a crucial global marketing platform. The partnership has set ambitious objectives for progressive improvement and will allow the two parties to develop their vision for the future, enabling Sauber Motorsport and Alfa Romeo to work on growing their success both on and off the track. Alfa Romeo’s presence in motorsports, and particularly in Formula One, will continue to play a key role in shaping the future of the brand, as it has since 1910. The partnership with Sauber will drive vehicle developments that Alfa Romeo will continue to transfer to production cars. This tech transfer has already proven that the benefits of this partnership are well beyond the confines of the race track, such as the development of the Giulia GTA and GTAm, the latest performance sedans by Alfa Romeo. Since its return to the sport in 2018, Alfa Romeo has developed new and exciting driving talent, such as Charles Leclerc and Antonio Giovinazzi, while bringing onboard an iconic name and former Formula One champion Kimi Räikkönen. -

Belgian Grand Prix 2014 Briefly

Summary Welcome in Spa-Francorchamp........................................................................... 2 FIA - Belgian GP: Map ........................................................................................ 3 Timetable ............................................................................................................. 4-5 Track Story .......................................................................................................... 6-7-8 Useful information ............................................................................................... 9-10 Media centre operation ........................................................................................ 11 Photographer’s area operation ............................................................................ 12 Press conference ................................................................................................ 13 Race Track Modification ...................................................................................... 14 Responsabilities Race Track ............................................................................... 15 Track information map ......................................................................................... 16 Track map ............................................................................................................ 17 Paddock map ....................................................................................................... 18 Belgian Grand Prix 2014 briefly .......................................................................... -

Avv. Alessandro Alunni Bravi Curriculum Vitae

AVV. ALESSANDRO ALUNNI BRAVI CURRICULUM VITAE 1 2 Personal Information Born: on 23/11/1974 in Umbertide, Italy Home address: Lugano, Switzerland Education: Graduated in Law with honors – Università degli Studi di Perugia (Italy) – Facoltà di Giurisprudenza; High School Diploma – Liceo Classico “Luca Signorelli” Cortona Professional summary: Lawyer; International Law, Civil Law and Sports Law specialist Languages: English, French, Italian Expertise: management, business development, legal counsel, corporate structuring, strategy, planning, budgeting, leadership, team management, contract negotiation Hobbies: historic rally co-driver (Lancia Rally 037 Group B), art, historic cars. 3 Present activities ALFA ROMEO RACING (Hinwil, Switzerland) From July 2017 General Counsel Alfa Romeo Racing is a Formula One Team which competes in the FIA Formula OneTM World Championship. SAUBER MOTORSPORT AG (Hinwil, Switzerland) From July 2017 Director, Secretary of the BoD, General Counsel Sauber Motorsport AG is the entity of Sauber Group of companies which operates and manages the Formula OneTM Team. For over 45 years, this innovative Swiss company has been setting standards in the design, development and construction of race cars for various championship series, such as Formula One, DTM, and WEC. Following its own Formula One debut in 1993, Sauber Motorsport AG has established one of the few traditional and privately held teams in the sport. After 25 years of competition in Formula OneTM, the company launched a long-term partnership with Title Sponsor Alfa Romeo in 2018 and enters the 2019 championship under the Team name Alfa Romeo Racing. ISLERO INVESTMENT AG (Hinwil, Switzerland) From March 2018 BoD member, Secretary of the BoD Islero Investment is the holding company which wholly owns Sauber Motorsport AG, Sauber Aerodynamik AG, Sauber Engineering AG and Sauber Technologies AG. -

AROCA July 2019 R0

2 Per SempreAlfa PRESIDENT John Anderson 0416 171 773 [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT Keith Faulkner 0403 878 749 [email protected] SECRETARY Robert Grant 0417 077 413 [email protected] TREASURER Garry Spowart (07) 4638 8663 - 0419 709 416 [email protected] MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Colin Densley 0404 043 254 [email protected] MAGAZINE COMMERCIAL ADS JudeVaughan (07) 3394 2517 - 0412 942 517 [email protected] SOCIAL CONVENOR Peter Mathews 0408 456 632 [email protected] COMPETITION CONVENOR MAGAZINE PACKAGING DISTRIBUTION Mark Jackson 0413122839 [email protected] VEHICLE DATING OFFICER Ken Percival (07) 3372 1769 - Contenuto DECEMBER 2019 0402 291 362 [email protected] LIFE MEMBERS Editoriale|MarkBuchanan 4 Robert and Shirley Grant Bernie and Jo-Anne CLUB NIGHT CO-ORDINATOR Campbell Presidente | John Anderson 6 Clare Cappa Peter Krespanis 0413 838 417 Laurie and Mary-Alice Trophy Winners Since 1980 | Mark Jackson 10 [email protected] Jones Richard Anderson SOCIAL MEDIA Denis Sando (Dec'd) Membri | Colin Densley 11 Steve Bowdery Jan Wickham 0408 659 858 Steve and Di Jones Sociale | Peter Mathews 12 [email protected] Ken and Kim Percival Keith Faulkner Tony and JudeVaughan Notizia 16 WEBMASTER Mark and Linda Jackson Keith Faulkner Garry Spowart 0403 878 749 Christmas Party Frolics – 8th December 18 [email protected] MEMBERS AT LARGE Doug Stonehouse - AROCA Members 23 MAGAZINE EDITOR 0415 954 939 Mark Buchanan Peter Mathews - Score at Motorclassica | By Barry Oosthuizen 23 0421 336 091 0408 456 632 [email protected] Tony Nelson John Ryan Competizione | Mark Jackson 26 MID-WEEK DRIVES Tony Nelson PATRON Resultati | Mark Jackson 28 [email protected] John French Gordon Murray T.50 Design Revealed32 Cover Photo Alfa Romeo 4C taken by Mark Buchanan - Marque Classificato 34 Photography @ Lakeside Italian Festival of Speed Eventi 36 Magazine Production Marque Photography Alfesta 38 www.marquephotography.com.au Finale 38 Per SempreAlfa 3 Editoriale | Mark Buchanan ill before we knew it Christmas arrived. -

2013 FIA Formula One World Championship Entry List

2013 FIA Formula One World Championship Entry List Date N° Driver’s Name Company Name Team Name Name of the Name of the Engine Chassis 23.10.2012 1 Sebastian VETTEL Red Bull Racing Ltd Red Bull Racing Red Bull Renault 23.10.2012 2 Mark WEBBER Red Bull Racing Ltd Red Bull Racing Red Bull Renault 29.10.2012 3 Fernando ALONSO Ferrari SPA Scuderia Ferrari Ferrari Ferrari 29.10.2012 4 Felipe MASSA Ferrari SPA Scuderia Ferrari Ferrari Ferrari 29.10.2012 5 Jenson BUTTON McLaren Racing Limited Vodafone McLaren McLaren Mercedes Mercedes 29.10.2012 6 Sergio PEREZ McLaren Racing Limited Vodafone McLaren McLaren Mercedes Mercedes 17.10.2012 7 Kimi RAIKKONEN Lotus F1 Team Limited Lotus F1 Team Lotus Renault 17.10.2012 8 TBA Lotus F1 Team Limited Lotus F1 Team Lotus Renault 26.10.2012 9 Nico ROSBERG Mercedes –Benz Grand Prix Ltd Mercedes Gp Mercedes Mercedes Petronas F1 Team 26.10.2012 10 LEWIS HAMILTON Mercedes –Benz Grand Prix Ltd Mercedes Gp Mercedes Mercedes Petronas F1 Team 29.10.2012 11 TBA Sauber Motorsport AG Sauber F1 Team Sauber Ferrari 29.10.2012 12 TBA Sauber Motorsport AG Sauber F1 Team Sauber Ferrari 28.10.2012 14 TBA Force India Formula 1 Team Ltd Sahara Force India Force India Mercedes F1 Team 28.10.2012 15 TBA Force India Formula 1 Team Ltd Sahara Force India Force India Mercedes F1 Team 29.10.2012 16 Pastor MALDONALDO Williams Gd Prix Engineering Ltd Williams F1 Team Williams Renault 29.10.2012 17 Valtteri BOTTAS Williams Gd Prix Engineering Ltd Williams F1 Team Williams Renault 26.10.2012 18 TBA Scuderia Toro Rosso SPA Scuderia Toro Toro Rosso Ferrari Rosso 26.10.2012 19 TBA Scuderia Toro Rosso SPA Scuderia Toro Toro Rosso Ferrari Rosso 15.10.2012 20 TBA 1Malaysia Racing Team Sdn Bhd Caterham F1 Team Caterham Renault 15.10.2012 21 TBA 1Malaysia Racing Team Sdn Bhd Caterham F1 Team Caterham Renault 26.10.2012 22 TBA Manor Grand Prix Racing Ltd Marussia F1 Team Marussia Cosworth 26.10.2012 23 TBA Manor Grand Prix Racing Ltd Marussia F1 Team Marussia Cosworth FIA - 30/11/2012 . -

Invoice BSR018

Born to be Wild Formula 1 e-mail contact details – you send them I’ll add them FOTA – Formula One Teams Association FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE DE L'AUTOMOBILE Rue de l'Arquebuse 12 – 1204 Geneva 8, Place de la Concorde Switzerland 75008 Paris Fax: +41.22.3108205 France Email: [email protected] Telephone: +33 1 43 12 44 55 Facsimilie: +33 1 43 12 44 55 Services Administratifs / Administration : 2, Chemin de Blandonnet 1215 Genève 15 Suisse / Switzerland Telephone: +41 22 544 44 00 Facsimile: +41 22 544 44 50 (Sport) Facsimile: +41 22 544 45 50 (Tourisme et Automobile) F1 Teams and Sponsors [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] info@sauber- motorsport.com [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] MPs [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] -

Additive Manufacturing in Formula 1®

Additive Manufacturing in Formula 1® Dipl. Ing. Christoph Hansen «Head of Additive Manufacturing» The Sauber Group › History The Sauber Group More than 45 years of history in motorsports 1970 1982 1988 1989 Founding of the First assignment to Sauber becomes the Sportscar world PP Sauber AG build a “Le Mans official Mercedes – championship title Prototype” Benz factory team. and double victory at the 24h of Le Mans Page 3 © Sauber Motorsport AG | All Rights Reserved The Sauber Group More than 45 years of history in motorsports 1993 2003 2006 2010 Formula 1 entry Construction of the BMW takes over the Peter Sauber bought own wind tunnel. Sauber Team back the Sauber F1 Team Page 4 © Sauber Motorsport AG | All Rights Reserved The Sauber Group More than 45 years of history in motorpsorts 2016 2018 The story continues… Don’t miss the Alfa Romeo Sauber F1 Team’s first race in Melbourne on March 25, 2018 Longbow Finance Alfa Romeo buys the Team. becomes the teams title Sponsor. Page 5 © Sauber Motorsport AG | All Rights Reserved Additive Manufacturing at Sauber › Development of AM at Sauber › AM on the F1® car › AM in the production of the race car › AM in aerodynamics › Third party business › The future of AM in the Sauber Team Page 6 © Sauber Motorsport AG | All Rights Reserved Additive Manufacturing at Sauber History › 1995 - 2007 The AM parts were purchased from external suppliers. › 2007 Set up of the own production Machines: 5 SLA 1 SLS › 2008 - 2018 Due to the rising demand of AM parts, the machine park had to be extended constantly. -

CH Feld Liste.Xlsx

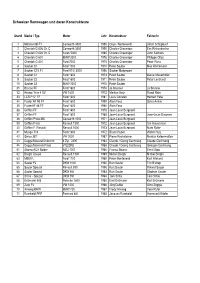

Schweizer Rennwagen und deren Konstrukteure Start# Marke / Typ Motor Jahr Konstrukteur Fahrer/in 1 Monteverdi F1 Cosworth 3500 1990 Onyx / Monteverdi Ulrich Schüpbach 2 Cheetah G 606 Gr. C Cosworth 3500 1990 Charles Graemiger Eric Rickenbacher 3 Cheetah G 604 Gr. C Aston 5400 1985 Charles Graemiger John Salmona 4 Cheetah G 601 BMW 2000 1976 Charles Graemiger Philippe Olloz 5 Cheetah G 501 Ford 2000 1975 Charles Graemiger Peter Wyss 6 Sauber C1 Ford 1000 1970 Peter Sauber Max Kilchemann 7 Sauber C15 F1 Ford V10/ 3000 1996 Sauber Motorsport 8 Sauber C3 Ford 1600 1973 Peter Sauber Daniel Mauerhofer 9 Sauber C2 Ford 1600 1971 Peter Sauber Peter Leuthardt 10 Sauber C5 BMW 2000 1975 Peter Sauber 31 Brucos FF Ford 1600 1978 Jo Brunner Jo Brunner 32 Horag / Has 4 SV VW 1600 1972 Markus Hotz Ruedi Rohr 33 LCR P12 FF Ford 1600 1981 Louis Christen Herbert Peter 34 Faster AF 90 FF Ford 1600 1990 Alain Feuz Giner Achim 35 FasterAF 86 FF Ford 1600 1986 Alain Feuz 36 Griffon FF Ford 1600 1978 Jean-Louis Burgnard 37 Griffon FF Ford 1600 1985 Jean-Louis Burgnard Jean-Louis Burgnard 38 Griffon Proto MC Cosworth 1000 1971 Jean-Louis Burgnard 39 Griffon Proto Renault 1300 1972 Jean-Louis Burgnard Urs Hauenstein 40 Griffon F. Renault Renault 1600 1973 Jean-Louis Burgnard Mark Rufer 41 Mungo T13 Ford 1300 1972 Bruno Huber Walter Hug 42 Swica 387 VW 2000 1987 Pierre Rechsteiner Markus Kalbermatten 43 Cegga Maserati Intercon. 4 Zyl. 2490 1964 Claude / Georg Gachnang Claude Gachnang 44 Cegga Maserati Proto V12/2953 1968 Claude / Georg Gachnang Georges Gachnang -

The Definitive Guide for Formula One

2018 The Definitive Guide for Formula One 1990 292018 by François-Michel GRÉGOIRE 2018 29 years of publication ON POLE IN GERMANY www.motorsport-magazin.com Multimedia format: online, print, mobile, video, social media Get in touch with German motorsport fans* 1,030,000 unique user in Germany* 1,691,461 unique user worldwide** Strong ability to mobilise opinion 405,000 Facebook fans*** 100% target group, 0% wastage rate, men & motors * AGOF internet facts 07-2017 ** Google Analytics 07-2017 *** https://www.facebook.com/motorsportmagazin 07-2017 2018 FIA Formula One World Championship SUMMARY TEAMS 19 DRIVERS 41 3RD - DEVELOPMENT - TEST DRIVERS 63 ENGINES 77 CARS 83 TEAM PRINCIPALS & CEO 95 ON POLE KEY PEOPLE 115 IN GERMANY SPONSORS & SUPPLIERS 409 www.motorsport-magazin.com MARKETING - PR - PRESS - EVENTS 497 JOURNALISTS & PHOTOGRAPHERS 635 Multimedia format: online, print, mobile, video, social media Get in touch with German motorsport fans* 1,030,000 unique user in Germany* GRAND PRIX 709 1,691,461 unique user worldwide** Strong ability to mobilise opinion 405,000 Facebook fans*** FOM - FIA 735 100% target group, 0% wastage rate, men & motors * AGOF internet facts 07-2017 ** Google Analytics 07-2017 *** https://www.facebook.com/motorsportmagazin 07-2017 2018 F1 SCHEDULE 2018 F1 SCHEDULE 2018 FIA FORMULA ONE Round Grand Prix Date Location 1 Rolex Australian Grand Prix 25 March Albert Park - Melbourne 2 Gulf Air Bahrain Grand Prix 8 April Bahrain International Circuit 3 Heineken Chinese Grand Prix 15 April Shanghai International Circuit -

News Release

News Release 3D Systems Corporation 333 Three D Systems Circle Rock Hill, SC 29730 www.3dsystems.com NYSE: DDD Investor Contact: Stacey Witten Email: [email protected] Agency Contact: Christopher Butcher Email: [email protected] Media Contact: Michael Swack Email: [email protected] Alfa Romeo Sauber F1® Team Adds Five 3D Systems ProX® 800 SLA 3D Printers to Win the Race Against Time for Part Production • New SLA 3D printers join Alfa Romeo Sauber F1® Team’s extensive arsenal of 3D Systems SLS and SLA solutions • Alfa Romeo Sauber F1® Team’s Additive Manufacturing services and expertise also available to 3rd parties ROCK HILL, South Carolina, June 19 2018 – 3D Systems (NYSE: DDD) announced that Sauber Motorsport AG, the company operating the Alfa Romeo Sauber F1® Team, has added five new ProX® 800 SLA 3D Printers to its headquarters and engineering facilities in Hinwil, Switzerland, within the scope of a new partnership agreement between 3D Systems and the Alfa Romeo Sauber F1® Team. Sauber Motorsport AG first started using 3D Systems’ solutions more than ten years ago when it built its Additive Manufacturing department. The new SLA (stereolithography) systems join existing 3D Systems products used by the F1 team, including six SLS 3D printers. “When we decided to upgrade our SLA production capability, we felt it was time to take our cooperation with 3D Systems to a deeper level. We also needed to expand our capacity so replacing some of the older 3D Systems SLA’s with the higher throughput ProX 800 was the 3D Systems Press Release Page 2 natural choice,” says Christoph Hansen, head of additive manufacturing, at Sauber.