The Island Monastery of Valaam in Finnish Homeland Tourism: Constructing a “Thirdspace” in the Russian Borderlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experimental Study of Municipal Solid Waste (Msw) Landfills and Non- Authorized Waste Damps Impact on the Environment

Linnaeus ECO-TECH ´10 Kalmar, Sweden, November 22-24, 2010 EXPERIMENTAL STUDY OF MUNICIPAL SOLID WASTE (MSW) LANDFILLS AND NON- AUTHORIZED WASTE DAMPS IMPACT ON THE ENVIRONMENT Veronica Tarbaeva Dmitry Delarov Committee on Natural Resources of Leningrad region, Russia ABSTRACT A purpose was an analysis of waste disposal sites existing in the Leningrad region and a choice of facilities potentially suitable for the removal and utilization of greenhouse- and other gases. In order to achieve the purpose in view, data were collected on the arrangement of non-authorized landfills and waste dumps within the Leningrad region. The preliminary visual evaluation and instrumental monitoring were carried out for 10 facilities. The evaluation of greenhouse- and other gas emissions into the atmosphere as well as of ground water pollution near places of waste disposal was performed. A databank was created for waste disposal sites where it could be possible to organize the work on removing and utilizing of greenhouse gas. The conducted examination stated that landfills exert negative influence on the environment in the form of emissions into the atmosphere and impurities penetrating underground and surface water. A volume of greenhouse gas emissions calculated in units of СО2 – equivalent from different projects fluctuates from 63.8 to 8091.4 t in units of СО2 – equivalent. Maximum summarized emissions of greenhouse gases in units of СО2 – equivalent were stated for MSW landfills of the towns of Kirishi, Novaya Ladoga and Slantsy, as well as for MSW landfills near Lepsari residential settlement and the town of Vyborg. KEYWORDS Non-authorized waste dumps, MSW landfills, greenhouse gases, atmospheric air pollution, instrumental monitoring. -

FSC National Risk Assessment

FSC National Risk Assessment for the Russian Federation DEVELOPED ACCORDING TO PROCEDURE FSC-PRO-60-002 V3-0 Version V1-0 Code FSC-NRA-RU National approval National decision body: Coordination Council, Association NRG Date: 04 June 2018 International approval FSC International Center, Performance and Standards Unit Date: 11 December 2018 International contact Name: Tatiana Diukova E-mail address: [email protected] Period of validity Date of approval: 11 December 2018 Valid until: (date of approval + 5 years) Body responsible for NRA FSC Russia, [email protected], [email protected] maintenance FSC-NRA-RU V1-0 NATIONAL RISK ASSESSMENT FOR THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION 2018 – 1 of 78 – Contents Risk designations in finalized risk assessments for the Russian Federation ................................................. 3 1 Background information ........................................................................................................... 4 2 List of experts involved in risk assessment and their contact details ........................................ 6 3 National risk assessment maintenance .................................................................................... 7 4 Complaints and disputes regarding the approved National Risk Assessment ........................... 7 5 List of key stakeholders for consultation ................................................................................... 8 6 List of abbreviations and Russian transliterated terms* used ................................................... 8 7 Risk assessments -

Large Russian Lakes Ladoga, Onega, and Imandra Under Strong Pollution and in the Period of Revitalization: a Review

geosciences Review Large Russian Lakes Ladoga, Onega, and Imandra under Strong Pollution and in the Period of Revitalization: A Review Tatiana Moiseenko 1,* and Andrey Sharov 2 1 Institute of Geochemistry and Analytical Chemistry, Russian Academy of Sciences, 119991 Moscow, Russia 2 Papanin Institute for Biology of Inland Waters, Russian Academy of Sciences, 152742 Yaroslavl Oblast, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 8 October 2019; Accepted: 20 November 2019; Published: 22 November 2019 Abstract: In this paper, retrospective analyses of long-term changes in the aquatic ecosystem of Ladoga, Onega, and Imandra lakes, situated within North-West Russia, are presented. At the beginning of the last century, the lakes were oligotrophic, freshwater and similar in origin in terms of the chemical composition of waters and aquatic fauna. Three stages were identified in this study: reference condition, intensive pollution and degradation, and decreasing pollution and revitalization. Similar changes in polluted bays were detected, for which a significant decrease in their oligotrophic nature, the dominance of eurybiont species, their biodiversity under toxic substances and nutrients, were noted. The lakes have been recolonized by northern species following pollution reduction over the past 20 years. There have been replacements in dominant complexes, an increase in the biodiversity of communities, with the emergence of more southern forms of introduced species. The path of ecosystem transformation during and after the anthropogenic stress compares with the regularities of ecosystem successions: from the natural state through the developmental stage to a more stable mature modification, with significantly different natural characteristics. A peculiarity of the newly formed ecosystems is the change in structure and the higher productivity of biological communities, explained by the stability of the newly formed biogeochemical nutrient cycles, as well as climate warming. -

Konevets Quartet

Presents Konevets Quartet Saturday, April 17, 7 p.m. PDST Presented ONLINE from St. Paul’s Episcopal Church Walnut Creek, California www.StPaulswc.org/concert-series Konevets Quartet Vocal Ensemble April 17, 2021 7pm PST Part I: Songs of Holy Easter 1. Communion hymn for saints – Хвалите Господа с небес, Trubachev The righteous shall be in eternal memory; He shall not fear evil tidings. Alleluia. 2. It is truly meet – Достойно есть, Chesnokov It is truly meet to venerate Thee, ever blessed and most pure Virgin and Mother of God. More honorable than the Cherubim and more glorious beyond compare than the Seraphim. Without defilement, thou gavest birth to God, the Word, true Theotokos, we magnify thee. 3. Who is so great a God as our God: Thou art the God who works wonders, Great Prokimenon 4. Blessed art Thou, O Lord – Благословен еси Господи, Znamenny chant Blessed art Thou, O Lord, teach me Thy statutes. The assembly of angels was amazed, beholding Thee numbered among the dead; yet, O Savior, destroying the stronghold of death, and with Thyself raising up Adam, and freeing all from hades. 5. Why hast Thou cast me away from Thy face - Вскую мя отринул еси, Chesnokov O Light that never sets, why hast thou rejected me from Thy presence, and why has alien darkness surrounded me, coward I am? But do thou I implore Thee direct my ways and turn me back towards the light of thy commandments 6. Easter Suite – Пасхальная сюита…., in four chants: Greek, Latin, two Georgians Let God arise, and let His enemies be scattered. -

Agriculture and Land Use in the North of Russia: Case Study of Karelia and Yakutia

Open Geosciences 2020; 12: 1497–1511 Transformation of Traditional Cultural Landscapes - Koper 2019 Alexey Naumov*, Varvara Akimova, Daria Sidorova, and Mikhail Topnikov Agriculture and land use in the North of Russia: Case study of Karelia and Yakutia https://doi.org/10.1515/geo-2020-0210 Keywords: Northern regions, land use, changes, agricul- received December 31, 2019; accepted November 03, 2020 tural development, agriculture, Russia, Karelia, Yakutia Abstract: Despite harsh climate, agriculture on the northern margins of Russia still remains the backbone of food security. Historically, in both regions studied in this article – the Republic of Karelia and the Republic 1 Introduction of Sakha (Yakutia) – agricultural activities as dairy - farming and even cropping were well adapted to local This article is based on the case study of two large admin – conditions including traditional activities such as horse istrative regions of Russian Federation the Republic of ( ) breeding typical for Yakutia. Using three different Karelia furthermore Karelia and the Republic of Sakha sources of information – official statistics, expert inter- (Yakutia). Territory of both regions is officially considered views, and field observations – allowed us to draw a in Russia as the Extreme North. This notion applies to the conclusion that there are both similarities and differ- whole territory of Yakutia, the largest unit of Russian ences in agricultural development and land use of these Federation and also the largest administrative region two studied regions. The differences arise from agro- worldwide with 3,084 thousand km2 land area. Five ad- climate conditions, settlement history, specialization, ministrative districts (uluses) of Yakutia have an access and spatial pattern of economy. -

1 Context Present ILO Activities

Partnership Annual Conference (PAC) Sixth Conference Oslo, Norway 25 November 2009 Reference PAC 6/5/Info 4 Title ILO Moscow technical cooperation activities related to the NDPHS – a report for the PAC Submitted by ILO Summary / Note - Requested action For information Context Under the auspices of the NDPHS two projects are operating in NW Russia: • ILO NW Russia OSH project; • FIOH/NDPHS Health at Work project (separate reporting). The ILO NW Russia OSH project is expected to be extended with a third and final phase for 2010-11. The ILO project has worked in close corporation with WHO/EURO, the WHO European CC meeting, the European OSH Agency, the FIOH project, the Baltic Sea OSH Network (BSN) on a regular basis. Details can be found below. A new link has been established with the project on Enhancing Expertise in Health Promotion and Occupational Health within Rehabilitation Professionals (EHORP) (funded by Finland through the NDPHS pipeline) in the Scientific and Practical Conference: “ Rehabilitation today: from functional recovery to healthy life style, the nation’s health improvement, social integration of disabled people ,and demographic transition on 22 October 2009. Further ILO has some other activities in the region. Present ILO activities ILO/IPEC action against child labour Before 2009 several practical models were developed by the IPEC Project to provide a direct support to families and children. They are: - Comprehensive rehabilitation of working street girls initially developed in St. Petersburg and later replicated in the city’s remote districts as well as in the Vssevolozhsk and Priozersk Districts of the Leningrad Region; later during the second phase of the Leningrad project it was applied in Vyborg. -

Fish and Fishing in Karelia Удк 597.2/.5+639.2(470.2) Ббк 28.693.32.(2Рос.Кар.) I-54

FISH AND FISHING IN KARELIA УДК 597.2/.5+639.2(470.2) ББК 28.693.32.(2Рос.Кар.) I-54 ISBN 978-5-9274-0651-7 © Karelian research centre RAS, 2014 FISH AND FISHING IN KARELIA N.V. ILMAST, O.P. STERLIGOVA, D.S. SAVOSIN PETROZAVODSK 2014 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE FRESHWATER FISH FAUNA OF KARELIA Karelian waters belong to drainage basins of two seas: the Baltic and the White Sea. The watershed between them runs across the central part of the republic. The hydrographic network is made up of numerous rivers and lakes grouped together into lake-river systems. The republic comprises nearly 50% of the water area of Lake Ladoga and 80% of Lake Onega, which are the biggest freshwater bodies in Europe. If lakes Onega and Ladoga are included, the lake cover of the territory (the ratio of the surface area of all lakes and the land area) is 21%. This is one of the highest values in the world. Migratory and salt-water fishes in Karelian waters are of marine origin, and the rest are of freshwater origin. Colonization of the region by freshwater fish fauna proceeded from south to north as the glacier was retreating. More thermophilic species (cyprinids, percids, etc.) colonized the waters some 10000 years B.P., and cold-loving species (salmons, chars, whitefishes, etc.) – even earlier. Contemporary freshwater fish fauna in Karelia comprises 44 fish species, excluding the typically marine species that enter the lower reaches of the rivers emptying into the White Sea (European plaice, Arctic flounder, navaga), farm-reared species (pink salmon, common carp, rainbow trout, longnose sucker, muksun, Arctic cisco, broad whitefish, northern (peled) whitefish, nelma/inconnu), as well as some accidental species (European flounder). -

The Role of the Republic of Karelia in Russia's Foreign and Security Policy

Eidgenössische “Regionalization of Russian Foreign and Security Policy” Technische Hochschule Zürich Project organized by The Russian Study Group at the Center for Security Studies and Conflict Research Andreas Wenger, Jeronim Perovic,´ Andrei Makarychev, Oleg Alexandrov WORKING PAPER NO.5 MARCH 2001 The Role of the Republic of Karelia in Russia’s Foreign and Security Policy DESIGN : SUSANA PERROTTET RIOS This paper gives an overview of Karelia’s international security situation. The study By Oleg B. Alexandrov offers an analysis of the region’s various forms of international interactions and describes the internal situation in the republic, its economic conditions and its potential for integration into the European or the global economy. It also discusses the role of the main political actors and their attitude towards international relations. The author studies the general problem of center-periphery relations and federal issues, and weighs their effects on Karelia’s foreign relations. The paper argues that the international contacts of the regions in Russia’s Northwest, including those of the Republic of Karelia, have opened up opportunities for new forms of cooperation between Russia and the EU. These contacts have en- couraged a climate of trust in the border zone, alleviating the negative effects caused by NATO’s eastward enlargement. Moreover, the region benefits economi- cally from its geographical situation, but is also moving towards European standards through sociopolitical modernization. The public institutions of the Republic -

In Search of Happy Gypsies

Norway Artctic Ocean Sweden Finland Belarus Ukraine Pacifc Ocean RUSSIA In Search of Kazahstan China Japan Mongolia Happy Gypsies Persecution of Pariah Minorities in Russia COUNTRY REPORTS SERIES NO. 14 Moscow MAY 2005 A REPORT BY THE EUROPEAN ROMA RIGHTS CENTRE European Roma Rights Centre IN SEARCH OF HAPPY GYPSIES Persecution of Pariah Minorities in Russia Country Report Series, No. 14 May 2005 Table of Contents Copyright: © European Roma Rights Centre, May 2005 All rights reserved. ISBN 963 218 338 X ISSN 1416-7409 Graphic Design: Createch Ltd./Judit Kovács Printed in Budapest, Hungary. For information on reprint policy, please contact the ERRC 5 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements....................................................................................................7 1. Executive Summary.............................................................................................9 2. Introduction: Anti-Romani Racism....................................................................19 3. A Short History of Roma in Russia ...................................................................43 4. Racially-Motivated Violence and Abuse of Roma by Law Enforcement Officials..............................................................................................................55 4.1 Racial Profiling ..........................................................................................57 4.2 Arbitrary Detention....................................................................................61 4.3 Torture -

The Museums of Lappeenranta 2015 2 South Karelia Museum and South Karelia Art Museum Joint Exhibition

Hugo Simberg, Sheep Girl, 1913. Tampere Art Society Museokuva. collection. Photo: Tampere 1913. Sheep Girl, Hugo Simberg, THE MUSEUMS OF LAPPEENRANTA 2015 2 SOUTH KARELIA MUSEUM AND SOUTH KARELIA ART MUSEUM JOINT EXHIBITION 26 April 2015 – 10 January 2016 Barefoot: 10 Lives in the Karelian Isthmus The museums at the fortress of Lappeenranta will host an exhibition displaying various perspectives of the Karelian isthmus, opening in the spring. Barefoot: 10 Lives in the Karelian Isthmus is a joint exhibition situated in both the South Karelia Museum and South Karelia Art Museum. The exhibition will be constructed round ten narrators. The narrators are real people. They represent various milieus and regions, various socioeconomic Leonid Andreyev and Anna Andreyeva in groups, women, men and children. Each the garden of the house at Vammelsuu. of them brings with them diff erent kinds Leeds University Library, Special Collections. of historical periods and events. They also bring a timeline to the exhibition which is organic and generational – not dictated on the State level or by political history. The individuals are new acquaintances to visitors to the museum and – presented in this new connection – they are surprising. They make a deep impression and rouse emotional reactions. Each person and his/her milieu are presented in the exhibition by means of short biographical text together with Janne Muusari, From the Harbour. photographs, as well as a wide variety of South Karelia Art Museum. objects, related collections and works of art. As a result, the exhibition does not compartmentalize the style of narration in the manner of art collections and historical collections: rather, the various types of ”evidence” in the exhibition are able to complement each other. -

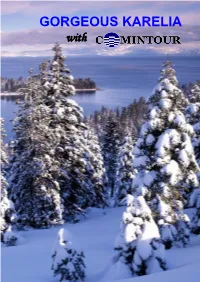

GORGEOUS KARELIA With

GORGEOUS KARELIA with 1 The tours presented in this brochure aim to country had been for centuries populated by the introduce customers to the unique beauty and Russian speaking Pomors – proud independent folk culture of the area stretching between the southern that were at the frontier of the survival of the settled coast of the White Sea and the Ladoga Lake. civilization against the harshness of the nature and Karelia is an ancient land that received her name paid allegiance only to God and their ancestors. from Karelians – Finno-Ugric people that settled in that area since prehistoric times. Throughout the For its sheer territory size (half of that of Germany) history the area was disputed between the Novgorod Karelia is quite sparsely populated, making it in fact Republic (later incorporated into Russian Empire) the biggest natural reserve in Europe. The and Kingdom of Sweden. In spite of being Orthodox environment of this part of Russia is very green and Christians the Karelians preserved unique feel of lavish in the summer and rather stern in the winter, Finno-Ugric culture, somehow similar to their but even in the cold time of the year it has its own Finnish cousins across the border. East of the unique kind of beauty. Fresh water lakes and rivers numbered in tens of thousands interlace with the dense taiga pine forest and rocky outcrops. Wherever you are in Karelia you never too far from a river or lake. Large deposits of granite and other building stones give the shores of Karelian lakes a uniquely romantic appearance. -

А. Kozeichouk September 27, 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY on T

IntelMedia Ltd. Affirmed by CEO IntelMedia Ltd. _______________________ А. Kozeichouk September 27, 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY on the services aimed at the creation of the most effective model of the cross-border cycling tourism on the territory of the Leningrad region under the contract № 1263 dated August 12, 2019 PART 5. Executive summary on the development of recommendations and activities for cycle tourism growth in the Leningrad region St. Petersburg 2019 Финансируется Европейским союзом, Российской Федерацией и Финляндской Республикой Within the project, recommendations and activities were developed for the cycle tourism growth in the Leningrad Region. To create a context for the development of recommendations, the following conclusions were made: ✓ Currently, the volume of tourist flows in the “cycle tourism” segment in the Priozersky and Vyborgsky districts of the Leningrad region remains at a negligible level. However, if measures are taken to develop cycle tourism, the border areas of the Leningrad region are able to demonstrate impressive volumes of the cycle tourists flow. ✓ The number of accommodation facilities in the border areas of the Leningrad region demonstrates a decline. In the Vyborgsky district, Vyborg city settlement accounts for almost 40% of all accommodation facilities. In the Priozersky district, accommodation facilities are distributed more evenly. Amount of accommodation facilities in the Vyborgsky district of the Leningrad region, 2014-2018 135 80 79 71 66 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2 Amount of accommodation facilities in the Priozersky district of the Leningrad region, 2014-2018 ✓ The average annual occupancy of accommodation facilities in the Priozersky and Vyborgsky districts of the Leningrad Region is about 60%, which is comparable to St.