State Notes TOPICS of LEGISLATIVE INTEREST Winter 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MCO and the DOC Have Agreed on the Following Bumping Regions for the Upcoming Prison Reorganization and Closures

KkyiEEPING YOU INFORMED JANUARY 9, 2009 BUMPING REGIONS ESTABLISHED --- VOLUNTARY TRANSFERS ALLOWED MCO and the DOC have agreed on the following bumping regions for the upcoming prison reorganization and closures: Deerfi eld F Mich. Reformatory, Bellamy Creek, I-Max, MTU Camp Branch F Lakeland & Florence Crane Scott F Ryan, Mound and Huron Valley Womens Huron Valley Mens F Parr Highway, Gus Harrison, Ryan, Mound & WHV To minimize the impact, the Department has agreed to allow those offi cers within the bumping regions to voluntarily transfer to vacancies throughout the state. Forms for this purpose will be made available by Monday at every facility within the regions cited above. Any offi cer within the bumping regions interested in transferring to other parts of the state will be required to submit the proper form to your personnel offi ce no later than the date specifi ed therein. You may list as many requests as you want. The determination for placement will be made strictly on operational needs and by seniority. This part of the process only relates to those who are interested in the possibility of transferring to other destina- tions. Do not list any institution within any bump region listed above as that request will be discounted. Note: There will be a different form for layoff and bumping when the institutions actually close. RELATED NEWS: TOUR SCHEDULE GENDER BASED ISSUES MCO President Tom Tylutki, MCO Staff and Board Members will be touring REARS ITS UGLY HEAD the facilities impacted by the closures next week. AGAIN! MONDAY, JANUARY 12, 2009 MCO recently learned it is the Tylutki & Kowitz - Camp Branch (1st & 2nd), Crane (2nd) Potter - I-Max (1st), MTU (2nd) Department’s intent to expand BFOQ assignments in the upcom- Tuesday, January 13, 2009 ing enlarged women’s prison. -

Michigan Department of Corrections

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ~-- - ------- ---------~- -------.-•.- ------------.-------- - C;/2~T Co-I '1-5'2..,.- Michigan Department of Corrections -, 9,000 t----t---t---t-----tf'r;;l---H-----1I-;-t--t---u 8,000 t-----+----f-t----+-----J'-=-+----t----r---ft--i--t----fl 7,000 I----I---A---V--t-----l----t------"d-t-----;-t----H 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 Michigan Department of Corrections <I. ,,1980 ~~ati§tical Presentation Governor William G. Milliken Corrections Director Perry M. Johnson CORRECTIONS COMMISSION Florence Crane~ Chairwolllan Robert G. Cotton, }":Dh.D. ~ Vice Chairlnan Thomas K. Eardley, Jr. Don LeDuc Duane Waters, M.D. 81996 u S Dt~,.Jartl':·<;' ,;~ .Jl!~;tt'~'t· N8.~iCPdll:l'~~:1 -11,· JU~tlLf r'-,';'" , '. ,',. " , .', , ! :' Distributed FalL 1981 Gail :8.. Light Michigan Dept. of Corrections r,-' '. '," ----- ------ Acknowledgements The statistical data in this report came primarily from information systems maintained by the Data Processing Division within the Bureau of Admin istrative Services. Information on court dispositions came from the various felony courts in Michigan. Those involved in the preparation and presentation of the statistics: Alvin L. Whitfield, Deputy Director of Bureau of Admih istrative Services Foreword William Kime, Deputy Director of Program Bureau Thk~rl~H!Ument is intended to provide researchers and other interested Gail R. Light and Calvin C. Goddard of the Office of Public persons with complete and accurate statistics on thestate1s correctional Information system for cal.endar year 1980. Information on various institutions, progr~s and bureaus can be obtained by contacting the office of Public InformatIOn Steve Paddock of the Data Processing Division for informa within the Michigan Department of Corrections. -

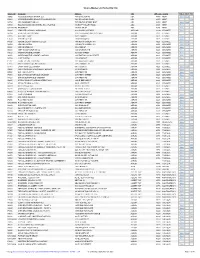

Source Master List Sorted by City

Source Master List Sorted By City Source ID Company Address City ZIP Code County Other* ROP PTI A2402 ACCESS BUSINESS GROUP, LLC 7575 E FULTON RD ADA 49355 KENT View View P0469 ACCESS BUSINESS GROUP-SPAULDING PLAZA 5101 SPAULDING PLAZA ADA 49355 KENT View N1784 ADA COGENERATION LLC 7575 FULTON STREET EAST ADA 49355 KENT View View N5183 HALLIDAY SAND AND GRAVEL, INC. - PLANT #4 866 EGYPT VALLEY ROAD ADA 49301 KENT View U411702145 RESIDENCE 645 ADA DR SE ADA 49341 KENT View B5921 LENAWEE CO ROAD COMMISSION 9293 ROUND LAKE HWY ADDISON 49220 LENAWEE View N7389 A & A CUSTOM CRUSHING GREEN HIGHWAY AND IVES ROAD ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View B2285 ACE DRILL CORP 2600 E MAUMEE ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View E8510 ADRIAN COLLEGE 110 S MADISON ST ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View P0426 ADRIAN ENERGY ASSOCIATES LLC 1900 NORTH OGDEN HWY ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View View N2369 ADRIAN LANDFILL 1970 NORTH OGDEN HWY ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View View B2288 ADRIAN STEEL CO 906 JAMES ST ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View B2289 AGET MANUFACTURING CO 1408 CHURCH ST E ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View N0629 ANDERSON DEVELOPMENT 525 GULF STREET ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View A2851 ANDERSON DEVELOPMENT COMPANY 1415 EAST MICHIGAN STREET ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View View N3196 CLIFT PONTIAC 1115 S MAIN ST ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View P1187 CORNERSTONE CRUSHING 1001 OAKWOOD ROAD ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View E8117 DAIRY FARMERS OF AMERICA INC 1336 E MAUMEE ST ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View B1754 ERVIN AMASTEEL DIVISION 915 TABOR ST. ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View View B2621 FLOYD’S RIGGING & MACHINERY MOVERS 831 DIVISION ST ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View B7068 GMI - HMA PLANT 19 2675 TREAT RD ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View View P0931 GMI CAT RDS-20 PORTABLE CRUSHER 2675 TREAT STREET ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View View N8221 GMI EXCEL PORTABLE CRUSHER 2675 TREAT RD ADRIAN 49221 LENAWEE View View B6027 INTEVA PRODUCTS ADRIAN OPERATIONS 1450 E. -

Corrections Line Item Summary FY 2002-03

LINE ITEM AND BOILERPLATE SUMMARY CORRECTIONS Fiscal Year 2002-03 Public Act 524 of 2002 Senate Bill 1102 As Enacted Prepared and Compiled by: Marilyn Peterson, Fiscal Analyst Tumai Burris, Budget Assistant Mitchell E. Bean, Director December 2002 HOUSE FISCAL AGENCY GOVERNING COMMITTEE Representatives: Marc Shulman, Chair A. T. Frank, Vice Chair Rick Johnson Samuel Buzz Thomas, III Bruce Patterson Gilda Jacobs MICHIGAN HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES APPROPRIATIONS COMMITTEE Representatives: Marc Shulman, Chair John Stewart Charles LaSata, Vice Chair Laura Toy Cameron Brown Jerry Vander Roest Sandra Caul A. T. Frank, Minority Vice Ch i Patricia Godchaux Richard Brown Mark Jansen Hansen Clarke Ron Jelinek Patricia Lockwood Jerry Kooiman Steve Pestka David Mead Clarence Phillips Mickey Mortimer James Plakas Gary Newell Triette Reeves John Pappageorge Keith Stallworth Mike Pumford Michael Switalski Scott Shackleton Gretchen Whitmer Tony Stamas STATE OF MICHIGAN HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES HOUSE FISCAL AGENCY MITCHELL E. BEAN, DIRECTOR GOVERNING COMMITTEE P.O. BOX 30014 MARC SHULMAN, CHAIR A. T. FRANK, V-C LANSING, MICHIGAN 48909-7514 RICK JOHNSON SAMUEL BUZZ THOMAS, III PHONE: (517)373-8080 FAX: (517)373-5874 BRUCE PATTERSON GILDA JACOBS www.house.state.mi.us/hfa December 2002 To: Members of the House of Representatives We have prepared a Line Item Summary for each of the FY 2002-03 appropriation acts. Each Summary contains line-by-line detail, including the amount and purpose of each appropriation line and information regarding related boilerplate sections, for a specific appropriation act. Following the line item detail, we have included a section that provides a brief explanation of each boilerplate section in the appropriations bill. -

MAP CFA-REGIONS SEPT 30 2009.Cdr

Michigan Department of Corrections Map Kewee- naw Correctional Facilities Administration n B Houghton Prison and Camp Facilities by Region As of September 30, 2009 l 2 Ontonagon Baraga Gogebic l 3 Luce Marquette Alger l4 n C l 5 Chippewa l 1 ll Schoolcraft ll 6 Iron Mackinac n A Dickinson Delta l INSTITUTIONS n CAMPS Emmet Cheboy- 1. Ojibway Correctional Facility Menominee gan A. Camp Ottawa1 Presque Isle 2. Baraga Max. Correctional Facility REGION I Charlevoix B. Camp Kitwen1 Alpena Otsego Mont- 3. Marquette Branch Prison* Antrim morency 4. Alger Max. Correctional Facility Leelanau C. Camp Cusino1 Grand n D Oscoda Alcona Benzie Kalkaska 5. Newberry Correctional Facility Traverse Crawford l 7 6. Chippewa Correctional Facility2 Ogemaw Iosco 6. Straits Correctional Facility2 Manistee Wexford Missau- Roscom- kee mon 6. Hiawatha Correctional Facility3 l8 Arenac 6. Kinross Correctional Facility l 9 7. Pugsley Correctional Facility Mason Lake Osceola Clare Gladwin 8. Oaks Correctional Facility Midland Bay 9. Standish Max. Correctional Facility Mecosta Isabella D. Camp Lehman l13 Huron 10. Earnest C. Brooks Correctional Facility Saginaw 10. Muskegon Correctional Facility Oceana Tuscola 10. West Shoreline Correctional Facility Neway- 2 go Sanilac 11. Carson City Correctional Facility l Muske- Montcalm ll12 11. Boyer Road Correctional Facility2 gon Gratiot 11l 12. Mid-Michigan Correctional Facility ll l Lapeer l 10 Ionia St. Clair 12. Pine River Correctional Facility Shia- Genesee Ottawa Kent lll Clinton wassee l15 12. St. Louis Correctional Facility ll 14 REGION II Ma- 13. Saginaw Correctional Facility Oakland comb Living- 14. Richard A. Handlon Correctional Facility Ingham ston n l16 Allegan Barry Eaton 14. -

A Study of the Differences Between Prison College Graduates and the Total Released Inmate Population on Recidivism by Risk Category

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 4-1982 A Study of the Differences Between Prison College Graduates and the Total Released Inmate Population on Recidivism by Risk Category James Jay Haviland Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Haviland, James Jay, "A Study of the Differences Between Prison College Graduates and the Total Released Inmate Population on Recidivism by Risk Category" (1982). Dissertations. 2499. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/2499 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STUDY OF THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN PRISON COLLEGE GRADUATES AND THE TOTAL RELEASED INMATE POPULATION ON RECIDIVISM BY RISK CATEGORY James Jay Haviland A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education Department of Educational Leadership Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April, 1982 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. A STUDY OF THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN PRISON COLLEGE GRADUATES AND THE TOTAL RELEASED INMATE POPULATION ON RECIDIVISM BY RISK CATEGORY James Jay Haviland, Ed.D. Western Michigan University, 1982 When a convicted felon is considered for parole from a correc tional institution, several factors relating to his experience while incarcerated are presented before the Parole Board. -

January, 2008

March, 2012 GENERAL MANAGEMENT PLAN Long-range management guidance focused on the specific natural resources, historic-cultural resources, recreation opportunities, and the education-interpretation opportunities of… Hartwick Pines State Park Prepared by: Paul N. Curtis, Park Management Plan Administrator Troy Rife, District Planner Josh Pellow, Planning Assistant Meredith Bohdan, Student Intern Anna Popp, Student Intern Brittany Blankenship, Management Planning Assistant PLAN APPROVALS: _____________________________ _____ Chief, Parks and Recreation Division Date _____________________________ _____ Deputy Director, Natural Resources Date __________________________________________ _____ Director, Michigan Department of Natural Resources Date 2 (Intentionally Blank for MSPAC Resolution) 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGES Executive Summary 7-9 Introduction 10 Planning Process Overview Planning Objectives Planning Team 11-12 Core Values 13-17 Department of Natural Resources (DNR) Mission Statement Parks and Recreation Division (PRD) Mission Statement Park Identity - Park Purpose - Park Significance Land Use and Legal Mandates/Restrictions Other Legal Mandates/Restrictions General Management Plan (20-YEAR LONG-RANGE GOALS). 18-35 Backcountry Zone Natural Resource Recreation Zone Developed Recreation Zone Visitor Services Zone Natural River Zone History Education Overlay Zone Cultural Landscape Overlay Zone Scenic Overlay Zone Future Plan Inserts 36 10-Year Action Plan (LONG-RANGE ACTION GOALS TO ATTAIN GMP) (INSERT) 5-Year Action Plan (SPECIFIC -

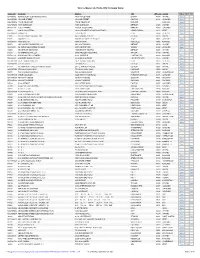

Source Master List Sorted by Company Name

Source Master List Sorted By Company Name Source ID Company Address City ZIP Code County Other* ROP PTI EN8200352 $2.50 QUALITY CLEANERS (LIVONIA) 37633 5 MILE ROAD LIVONIA 48154 WAYNE View U631903952 154 LAKE STREET 154 LAKE STREET PONTIAC 48311 OAKLAND View U561505076 1708 E ASHMAN ST 1708 E ASHMAN ST MIDLAND MIDLAND View U821606073 19455 GLENDALE 19455 GLENDALE DETROIT 48223 WAYNE View EN6300187 2.20 CLEANERS 28505 N. WOODWARD BERKLEY 48072 OAKLAND View N1511 2/90 SIGN SYSTEMS 5350 CORPORATE GROVE BOULEVARD GRAND RAPIDS 49512 KENT View U251905938 2019-021-10 1726 LEITH ST. FLINT 48506 GENESEE View P1004 21ST CENTURY SALVAGE, INC. 866 TERMINAL STREET DETROIT 48214 WAYNE View P0376 2600 WBB, LLC 2600 WEST BIG BEAVER ROAD TROY 48084 OAKLAND View View U501901331 30000 GRATIOT 30000 GRATIOT ROSEVILLE 48066 MACOMB View B3079 3401 MARTIN PROPERTIES, LLC 3401 MARTIN ROAD DETROIT 48210 WAYNE View U63142671 3M ABRASIVE SYSTEMS DIVISION 30975 CENTURY DR WIXOM 48393 OAKLAND View N2999 3M DETROIT ABRASIVES 11900 E EIGHT MILE RD DETROIT 48205 WAYNE View View P0621 3S INTERNATIONAL LLC 27050 TROLLEY INDUSTRIAL TAYLOR 48180 WAYNE View EN5000133 4 SEASONS DRY CLEANERS 42131 GARFIELD CLINTON TWP 48038 MACOMB View EN8200361 40 MINUTE INDIAN VILLAGE 20948 MACK AVENUE GRSSE PTE WDS 48236 WAYNE View U251910449 416 S. GRAND TRAVERSE 416 S. GRAND TRAVERSE FLINT 48506 GENESEE View U822002849 5124 MITCHELL 5124 MITCHELL DETROIT 48211 WAYNE View P1153 555 NONPROFIT GALLERY AND STUDIOS 2941 E. WARREN AVENUE DETROIT 48207 WAYNE View U081807050 5769 HEAD LAKE ROAD -

46949NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. · . '~>dimensions A report of the Michigan-Department of Corrections - William G. Milliken, governor Perry M. Johnson, director Corrections Commission: G. Robert Cotton, Ph.D., chairperson Thomas K. Eardley, Jr., vice chairperson B. James George, Jr. Florence R. Crane Duane L. Waters, M.D. Gail R. Light, editor Distributed _ Winter, 1977 \! 1;t-~/ ~ f ¥~:" i" r~; :1 i. ii foreword Presentation of material in this report is very similar to the 1975 Dimensions. Some changes have been made, however, to bring the various narrative sections up-to-date through mid-1977. The statistical charts and graphs cover the 1976 calendar year, except where noted otherwise. Some major changes worth noting: The addition of a section on the Riverside Correctional Facility at Ionia, a newly acquired institution for men; a new statistical presentation on critical incidents in Michigan institutions in 1976; a more complete statistical presentation of the average school grade rating by 1.0. groups of 1976 commitments; a new statistical presentation on parole contracts. - the editor iii em nt The statistical data in this report came primarily from information systems maintained by the Data Systems Section, Management Services Division within the Bureau of Administrative Services. Information on court dispositions came from the various felony courts in Michigan. Those involved in the preparation and presentation of the statistics: Jack A. Boehm, administrator of the Management Services Division William Kime, deputy director in charge of the Program Bureau Richard L. Shinevar and Donald L. Matthews of the Data Systems Section Diana M. -

Prison and Camp Closures by Lindsay Hollander, Fiscal Analyst

State Notes TOPICS OF LEGISLATIVE INTEREST May/June 2009 Prison and Camp Closures By Lindsay Hollander, Fiscal Analyst In the wake of budget reductions across State government, the Michigan Department of Corrections (MDOC) has been working to reduce the prison and camp population over the past two years in order to close correctional facilities. After reaching a high of 51,544 prisoners in April 2007, the MDOC population is now at an eight-year low of 47,264 prisoners. By the end of 2009, the MDOC plans to have a population of 45,433 in order to close three prisons and five camps. Table 1 lists the proposed closures, as well as a history of correctional facility closures. Figure A provides an illustration of this closure history. Facility closures over the past five years have resulted in $155.8 million of annual savings. This is primarily the result of the 1,841.8-position reduction in full-time equated (FTE) positions. In order to realize additional savings in the Department, the fiscal year (FY) 2009-10 Governor's recommended MDOC appropriations included savings of $118.0 million for unspecified facility closures. The House-passed version of House Bill 4437, the FY 2009-10 MDOC budget bill, included this $118.0 million savings for facility closures. Following the announcement of the eight facility closures on June 5, 2009, the Senate passed a version of House Bill 4437 that eliminated funding for these facilities. Approximately 1,072.0 FTE positions would be eliminated. However, according to the MDOC, the number of employees laid off could be as low as 500 to 700, depending on the number of employees who choose to fill other vacancies or retire. -

No Way out CAPPS

No way out Michigan’s parole board redefines the meaning of “life” APPS CITIZENS ALLIANCE ON PRISONS & PUBLIC SPENDING No way out Michigan’s parole board redefines the meaning of “life” September, 2004 APPS CITIZENS ALLIANCE ON PRISONS & pUBLIC sPENDING Additional copies of this report may be purchased for $7, including shipping. The full report is also available on the CAPPS website: www.capps-mi.org. Citizens Alliance on Prisons and Public Spending 115 W. Allegan St., Suite 850 Lansing, MI 48933 Tel: 517-482-7753 Fax: 517-482-7754 E-Mail: [email protected] Contents Preface 1 Introduction 3 Multiple views on the meaning of life 5 • Michigan’s Lifer Law - then and now 7 • The view from the bench 14 • The view from other states 17 • The view from inside 19 • Should lifers be paroled? A review of the relevant facts 22 Prisoner profiles 27 • About these profiles 29 • Henry Phillips 31 • Reynaldo Rodriguez 32 • Gladys Wilson 34 • Leslie G. Moran 35 • James R. Percy 37 • Martin Vargas 38 • Gregory Lawrence & Robert Schraw 41 • Ross Stephen Hayes 44 • Michelle Bazzetta-Southers 45 • Gerald Lee Hessell 47 • Jose Daniel Mares 49 • Anthony Johnson 50 • Derek Lee Foster 52 • David Closser 53 • Philandius Ford 55 • Monica Jahner 57 • Robert Weisenauer 58 • Kenneth Foster 60 • Ruth Bullock 62 • The view from then to now 64 Recommendations for change 67 Acknowledgments 72 Preface There are two kinds of life sentences in Michigan. Life without the possibility of parole is mandatory for the crime of first-degree murder. Parolable life is one alternative judges can choose for many other of- fenses. -

Pro Bono Sembiar November 16, 2005

Pro Bono Sembiar November 16, 2005 Sponsored by Eastern District of Michigan Chapter The United States District Court The Federal Bar Association Eastern District ofMichi~an Eastern District ofMichz~an UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN AND THE FEDERAL BAR ASSOCIATION PRO BONO TRAINING SEMINAR November 16, 2005 PROGRAM 8:30 a.m. Registration and Continental Breakfast 9:00 a.m. Welcome and Introduction Denise Page Hood, U.S. District Judge and Julia Pidgeon, President, FBA 9:15 a.m. “Overview ofPrison Litigation Reform Act” (Tab 1) Wallace Capel, Jr., U.S. Magistrate Judge 9:40 a.m. “The Elements ofa Prisoner’s Civil Rights Claim” (Tab 2~) Erica M. Eisinger, Clinical Director, Wayne State University Law School 10:00 a.m. “Proving Your Case” - Patricia Streeter, Civil Rights Attorney (Tab 3) 10:20 a.m. ‘Magistrate Judges’ Involvement in Prison Cases” (Tab 4~) Steven Pepe, U.S. Magistrate Judge 10:30a.m. BREAK 10:50 a.rn. “Federal Judges’ Involvement in Prison Cases” (Tab 5) Avern Cohn, U.S. District Judge 11:10 a.m. “The Learning Experience ofPrison Cases” (Tab 6) Arthur Tarnow, U.S. District Judge 11:25 a.m. “Reimbursement ofExpenses and Other Things to Know” (Tab 7,) David J. Weaver, Court Administrator 11:35 a.m. “Dealing with Defendants’ (‘ounsel and the Michigan Depart. of (‘orrections” Leo Friedman, Assistant Attorney General, Corrections Division (Tab 8) 11:55 a.m. “Establishing a Relationshz:p with Your Client” (Tab 9,) Daniel Manville, Clinical Staff Attorney, Wayne State University Law School 12:10 p.m.