From Marple to Hay and Back

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SA-SIG Newsletter P Ostal S Ubscription F

-SU A-SIG U The journal of the Southern African Jewish Genealogy Special Interest Group http://www.jewishgen.org/SAfrica/ Editor: Colin Plen [email protected] Vol. 14, Issue 1 December 2013 InU this Issue President’s Message – Saul Issroff 2 Editorial – Colin Plen 3 Meir (Matey) Silber 4 South African Jews Get Their Master Storyteller – Adam Kirsch 5 A New Diaspora in London – Andrew Caplan 8 Inauguration of Garden Route Jewish Association as SAJBD affiliate 11 From Lithuania to Mzansi: A Jewish Life – Walter and Gordon Stuart 12 Preserving our Genealogy Work for Posterity – Barbara Algaze 13 The Dunera Boys 15 2013 Research Grant Recipients for IIJG 16 New Items of Interest on the Internet – Roy Ogus 17 Editor’s Musings 20 Update on the Memories of Muizenberg Exhibition – Roy Ogus 22 New Book – From the Baltic to the Cape – The Journey of 3 Families 23 Book Review – A Dictionary of Surnames – Colin Plen 24 Letters to the Editor 25 © 2013 SA-SIG. All articles are copyright and are not to be copied or reprinted without the permission of the author. The contents of the articles contain the opinions of the authors and do not reflect those of the Editor, or of the members of the SA-SIG Board. The Editor has the right to accept or reject any material submitted, or edit as appropriate. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE The Southern Africa Jewish Genealogy In August I attended the annual IAJGS conference in Boston. I think about 1200 people were there and Special Interest Group (SA-SIG) I was told that several hundred watched the sessions The purpose and goal of the Southern Africa Special live using a new on-line streaming system. -

European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960

INTERSECTING CULTURES European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960 Sheridan Palmer Bull Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy December 2004 School of Art History, Cinema, Classics and Archaeology and The Australian Centre The University ofMelbourne Produced on acid-free paper. Abstract The development of modern European scholarship and art, more marked.in Austria and Germany, had produced by the early part of the twentieth century challenging innovations in art and the principles of art historical scholarship. Art history, in its quest to explicate the connections between art and mind, time and place, became a discipline that combined or connected various fields of enquiry to other historical moments. Hitler's accession to power in 1933 resulted in a major diaspora of Europeans, mostly German Jews, and one of the most critical dispersions of intellectuals ever recorded. Their relocation to many western countries, including Australia, resulted in major intellectual and cultural developments within those societies. By investigating selected case studies, this research illuminates the important contributions made by these individuals to the academic and cultural studies in Melbourne. Dr Ursula Hoff, a German art scholar, exiled from Hamburg, arrived in Melbourne via London in December 1939. After a brief period as a secretary at the Women's College at the University of Melbourne, she became the first qualified art historian to work within an Australian state gallery as well as one of the foundation lecturers at the School of Fine Arts at the University of Melbourne. While her legacy at the National Gallery of Victoria rests mostly on an internationally recognised Department of Prints and Drawings, her concern and dedication extended to the Gallery as a whole. -

The Hidden History Retold in Hay's Museums

The Hidden History retold in Hay's Museums Hay Public School Creative Catchment Kids Creative Catchment Kids is an initiative of Wirraminna Environmental Education Centre. It aims to improve engagement between our funding partners and school students by providing opportunities for positive, cooperative activities that encourage students to learn about and respond to, natural resource management and the importance of agricultural production. wirraminna.org.au/petaurus/creative-catchment-kids/ Petaurus Education Group Petaurus Education Group identifies, develops and delivers a range of learning and curriculum experiences, resources and initiatives for schools and community groups to connect with land, water, productive farming, sustainability and cultural issues at the local level. The group was established by Wirraminna Environmental Education Centre in late-2014 to support its operations and education activities. petaurus.org.au Enviro-Stories Enviro-Stories is an innovative literacy education program that inspires learning about natural resource and catchment management issues. Developed by PeeKdesigns, this program provides students with an opportunity to publish their own stories that have been written for other kids to support learning about their local area. envirostories.com.au The Hidden History retold in Hay's Museums Authors: Wendy Atkins, Tyson Blayden, Meagan Foggo, Miranda Griffiths, Keira Harris, Andrew Johnston, Clare Lauer, Savannah Mohr, Zoe Ndhlovu and Daniel Wilson. School: Hay Public School Teacher support: Fleur Cullenward I N N A M A R R I E R W T N E E C N V N IR O O TI NM CA ENTAL EDU BURRUMBUTTOCK © 2020 Wirraminna Environmental Education Centre, wirraminna.org.au Design by PeeKdesigns, peekdesigns.com.au Welcome to Hay Our little town of Hay in south-west NSW has all you need, from fantastic shops to riverside trails. -

With Fond Regards

With Fond Regards PRIVATE LIVES THROUGH LETTERS Edited and Introduced by ELIZABETH RIDDELL ith Fond Regards W holds many- secrets. Some are exposed, others remain inviolate. The letters which comprise this intimate book allow us passage into a private world, a world of love letters in locked drawers and postmarks from afar. Edited by noted writer Elizabeth Riddell, and drawn exclusively from the National Library's Manuscript collection, With Fond Regards includes letters from famous, as well as ordinary, Australians. Some letters are sad, others inspiring, many are humorous—but all provide a unique and intimate insight into Australia's past. WITH FOND REGARDS PRIVATE LIVES THROUGH LETTERS Edited and Introduced by Elizabeth Riddell Compiled by Yvonne Cramer National Library of Australia Canberra 1995 Published by the National Library of Australia Canberra ACT 2600 © National Library of Australia 1995 Every reasonable endeavour has been made to contact relevant copyright holders. Where this has not proved possible, the copyright holders are invited to contact the publishers. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry With fond regards: private lives through letters. ISBN 0 642 10656 8. 1. Australian letters. 2. Australia—Social conditions—1788-1900. 3. Australia—Social conditions—20th century. 4. Australia—Social life and customs—1788-1900. 5. Australia—Social life and customs— 20th century. I. Riddell, Elizabeth. II. Cramer, Yvonne. III. National Library of Australia. A826.008 Designer: Andrew Rankine Editor: Susan -

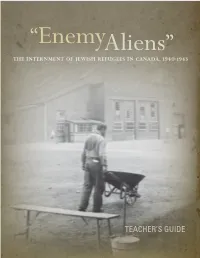

Complete Teachers' Guide to Enemy

“EnemyAliens” The Internment of Jewish Refugees in Canada, 1940-1943 TEACHER’S GUIDE “ENEMY ALIENS”: The Internment of Jewish Refugees in Canada, 1940-1943 © 2012, Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre Lessons: Nina Krieger Text: Paula Draper Research: Katie Powell, Katie Renaud, Laura Mehes Translation: Myriam Fontaine Design: Kazuko Kusumoto Copy Editing: Rome Fox, Anna Migicovsky Cover image: Photograph of an internee in a camp uniform, taken by internee Marcell Seidler, Camp N (Sherbrooke, Quebec), 1940-1942. Seidler secretly documented camp life using a handmade pinhole camera. − Courtesy Eric Koch / Library and Archives Canada / PA-143492 Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre 50 - 950 West 41st Avenue Vancouver, BC V5Z 2N7 604 264 0499 / [email protected] / www.vhec.org Material may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes provided that the publisher and author are acknowledged. The exhibit Enemy Aliens: The Internment of Jewish Refugees in Canada, 1940 – 1943 was generously funded by the Community Historical Recognition Program of the Department of Citizenship, Immigration and Multiculturalism Canada. With the generous support of: Oasis Foundation The Ben and Esther Dayson Charitable Foundation The Kahn Family Foundation Isaac and Sophie Waldman Endowment Fund of the Vancouver Foundation Frank Koller The Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre gratefully acknowledges the financial investment by the Department of Canadian Heritage in the creation of this online presentation for the Virtual Museum of Canada. Teacher’s Guide made possible through the generous support of the Mordehai and Hana Wosk Family Endowment Fund of the Vancouver Holocaust Centre Society. With special thanks to the former internees and their families, who generously shared their experiences and artefacts in the creation of the exhibit. -

Dunera News, June 2016

A publication for former refugees from Nazi and Fascist persecution (mistakenly shipped to and interned Dunera in Australia at Hay and Tatura, many later serving with the Allied Forces), News their relatives and their friends. No. 97 June 2016 75th Anniversary Tatura Reunion Bern Brent, Bernhard Rothschild, Reinhold Eckfeld Foundation Editor: Enemies and Aliens From the President The late Henry Lippmann OAM A war refugee, wrongly interned Editorial responsibility: out of fear, faces the trauma of his The Committee of the Dunera Association incarceration while his Australian Dunera Association on facebook guards and the nearby country – Friends of the Dunera Boys town need to learn that the real enemy is the one within and not Rebecca Silk In this edition we report on the highly successful 75th anniversary Letters and articles for publication are welcome. the one imagined. President reunion at Tatura. Over 40 people attended, many for the first Email: [email protected] Dunera Association The story, inspired by real time. We were privileged to have three Dunera Boys at Tatura: events surrounding the internment Bern Brent, Bernhard Rothschild and Reinhold Eckfeld. It was of the Dunera Boys, explores such a joy to see Dunera families making connections and interrelations and attitudes in a visiting the campsites. Once again Bern Brent has penned an social melting pot. It challenges interesting piece (page 9), this time about Tatura and the status the reader to ponder the age-old of the various categories of internees on HMT Dunera. dilemma of keeping refugees in We heard from some interesting speakers at the gathering at detention, to consider the issue the Tatura museum, including Christina McNab, granddaughter of cultural practises born from of the McNab family who owned the orchard where some religious beliefs and above all to internees worked prior to their army service. -

War and Peace: 200 Years of Australian-German Artistic Relations

Rex Butler & A.D.S. Donaldson, War and Peace: 200 years of Australian-German Artistic Relations REX BUTLER & A.D.S. DONALDSON War and Peace: 200 Years of Australian-German Artistic Relations The guns were barely silent on the Western Front when on 23 November 1918 Belgian-born Henri Verbrugghen took to the stage of the recently established NSW Conservatorium and softly tapped his baton, bringing the audience to silence. Then into this silence Verbrugghen called down the immortal opening chords of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the ‘Choral’, with its celebrated fourth movement ‘Ode to Joy’, based on Schiller’s words. A difficult piece to stage because of the considerable orchestral forces required, the performance was nevertheless a triumph, and all the more so for the occasion it marked, the Allied victory over Germany. Due to the long lead time and the necessity for extensive rehearsal, its being played at the signing of peace was a coincidence, but nevertheless a very serendipitous one. And the point was not lost on the critic for the Sydney Morning Herald, who in their review wrote: The armistice and the blessings of peace were not in sight when the program of the Conservatorium Orchestra on Saturday afternoon was projected, but by an extraordinary coincidence the inclusion of Beethoven’s ‘Choral Symphony’ with the Ode to ‘Joy, thou spark from Heaven descending’, brought the whole body of players and singers into line for the celebration of the glorious Allied victory.1 The real coincidence here was perhaps not the fortuitous programming of Beethoven at the moment of the signing of the Treaty at Versailles, but that of Germany and Australia itself. -

Finding Aid (English)

https://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection WILHELM BAUMANN PAPERS, 1928-1980 2015.254.1 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place SW Washington, DC 20024-2126 Tel. (202) 479-9717 e-mail: [email protected] Descriptive summary Title: Wilhelm Baumann papers Dates: 1928-1980 (bulk, 1939-1948) Accession number: 2015.254.1 Creator: Baumann, Wilhelm Extent: 1.2 linear feet (2 boxes, 2 oversize folders) Repository: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives, 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place SW, Washington, DC 20024-2126 Abstract: The Wilhelm Baumann papers consist largely of correspondence, immigration documents, educational records, identification documents, newspapers, and ephemera. The records document the emigration of Baumann and his parents from their native Austria in 1939, his life in the United Kingdom and subsequent classification as an enemy alien, his subsequent deportation to Australia in 1940 on the HMT Dunera, and his experiences in two internment camps in New South Wales and Victoria (Camp Hay and Camp Tatera). The collection also contains an extensive selection of his correspondence with other German and Austrian Jewish émigrés in Australia and elsewhere, his subsequent release the camps and activities in the Jewish communities of Victoria, and his immigration to the United States, including his reunion with his parents, in 1947. Languages: German, English, Hebrew Administrative Information Access: Collection is open for use, but is stored offsite. Please contact the Reference Desk more than seven days prior to visit in order to request access. Reproduction and use: Collection is available for use. Material may be protected by copyright. -

HMT Dunera and Hay

HMT Dunera and Hay A series of etchings by Alex Byrne AM Exhibition at Hay Shire Library September – October 2018 1 The Dunera Story The story of the ‘Dunera Boys’ links the horrors of the rise of the Nazi Party and the Holocaust to Hay in the Australian Riverina during the Second World War and to modern, multicultural Australia. As the Nazis tightened their grip on Germany and intensified their measures against Jews, Rom (Gypsies), homosexuals and other ‘undesirables’, those who could sought refuge in other countries. The need to assist their escape intensified after Kristallnacht, the violent anti-Jewish pogroms in November 1938. Most dramatic was the rescue of 10,000 children by the Kindertransport. When the Second World War was declared, the refugees who had settled in Britain were classified as ‘Enemy Aliens’ but relegated to a lower category. Following the loss of France and the occupation of most of western Europe, the British authorities succumbed to public panic and decided that adult male enemy aliens should be removed with three shiploads destined for Canada and one for Australia. One, the Arandora Star, was torpedoed in the Atlantic with 805 drowned. HMT Dunera was a troopship that had taken New Zealand soldiers to the Middle East. Assigned to the task of removing enemy aliens, the Dunera took 2,542 detainees at Liverpool on 10 July 1940. They included some rescued from the Arandora Star and predominantly consisted of Jewish refugees among the 2,036 anti-Nazis along with some 500 Italian and German prisoners of war and Nazi sympathisers. -

Sinking of Andora St

English Translated to: English Show original Powered by Translate 2:08:10 German against German 70 years ago a submarine sank the luxury liner "Arandora Star. At least 800 people died, many of them were German in British exile. By the accident was one of the biggest blunders of the British government to light - its rigid policy toward Nazi refugees by Lars-Broder Keil The second day at sea is just a few days ago, when life awakens on board the Arandora Star "slowly. The former luxury liner has left the English coast behind and crossed the Irish Sea. Rainer Radok is at this second July 1940 shortly before six clock up to get breakfast for his brothers and himself. The 20-year-old is not voluntary on the ship. Just as the other 1200 passengers: German prisoners of war, Nazi supporters, but also German and Austrian immigrants, and about 800 Italians. They had all been provisionally detained in the turmoil of war by British authorities and should now be brought to Canada. The fear of an invasion of the Wehrmacht adopted the British public hysterical traits. Is almost paranoid distrust of all Germans in the country - even to Jews as Rainer Radok, who was lucky to escape with the Nazi terror in 1938 in Konigsberg. An explosion rocked the ship, the light goes out, smoke spreads. "U-boat attack," shouted one soldier and urges Radok towards the upper deck. But the young man wants to go back to his cabin to warn his brothers. He whistled a signal from childhood times, and is glad when he gets answers. -

ANU Historical Journal II: Number 1

In loving memory of Anne Kingston (1942–68) ANU HISTORICAL JOURNAL II NUMBER 1 Contents Editorial: A history . .. v Emily Gallagher Acknowledgements . xiii Emily Gallagher, Jessica Urwin and Madalyn Grant Memoirs Special: Remembering the ANU Historical Journal (1964–87) Beginnings—Some reflections on the ANU Historical Journal, 1964–70 . 3 Ron Fraser Old and new Australia . 15 Alastair Davidson Memories of the ANU Historical Journal . 25 Caroline Turner My brilliant apprenticeship . 31 Ian Britain The past is another truth . 35 Rosemary Auchmuty An old and agreeable companion, 1972–74 . 39 Doug Munro The wider significance of the ANU Historical Journal . 47 Jill Waterhouse Articles ‘Ours will be a tent’: The meaning and symbolism of the early Aboriginal Tent Embassy . .. 57 Tobias Campbell A new dawn: Rights for women in Louisa Lawson’s The Dawn . 73 Ingrid Mahony Cultural responses to the migration of the barn swallow in Europe . 87 Ashleigh Green Kingship, sexuality and courtly masculinity: Frederick the Great and Prussia on the cusp of modernity . 109 Bodie A Ashton Lebanon’s ‘age of apology’ for Civil War atrocities: A look at Assad Shaftari and Samir Geagea . 137 Nayree Mardirian ‘O Sin, Sin, what hast thou done!’: Aboriginal people and convicts in evangelical humanitarian discourse in the Australian colonies, 1830–50 . 157 Tandee Wang Object study—The Tombstone of Anne: A case study on multilingualism in twelfth‑century Sicily . 179 Sarah MacAllan Lectures Inaugural Professorial Lecture—Is Australian history still possible? Australia and the global eighties . 193 Frank Bongiorno Geoffrey Bolton Lecture—From bolshevism to populism: Australia in a century of global transformation . -

Dunera in Australia at Hay and Tatura, Many Later Serving with the Allied Forces), News Their Relatives and Their Friends

A publication for former refugees from Nazi and Fascist persecution (mistakenly shipped to and interned Dunera in Australia at Hay and Tatura, many later serving with the Allied Forces), News their relatives and their friends. No. 95 October 2015 Foundation Editor: Conversations on facebook From the President The late Henry Lippmann OAM We invite you to take a look at our facebook page to see news from the Editorial responsibility: Dunera community around the globe. The Committee of the Dunera Association Letters and articles for publication are welcome. Rebecca Silk Welcome to our spring edition of the Dunera News for 2015. Email: [email protected] President We report on our highly successful 75th anniversary reunion Dunera Association events. You will see pictures and first hand reports from a Cover image: wonderful weekend in Hay where 80 people attended, Bernard Rothschild and Werner Haarburger 75th Anniversary, Hay Dunera weekend. representing 27 internees. We were thrilled that Dunera Boys Hay Railway Station. 5 Sep 2015 Bernard Rothschild and Werner Haarburger were there with their Story on page 4 families. We are most grateful to our friends at the Hay Dunera Portrait of Julius Spier, approximately 1942. Museum, led by David Houston, for organising the program. By Theodor Engel A special highlight was the cameo play performed by Hay War CONTENTS memorial High School students under the guidance of history From: Jennifer Sanders Spier Stern teacher Fiona Harrison. From the President 3 This portrait of my father hangs in the National Library of Australia in We also report on a lively reunion held in Sydney at the Sydney Dunera 75th Reunion in Hay 4 Canberra.