Finlay on Martin Guerre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Kiss Today Goodbye, and Point Me Toward Tomorrow”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By BRYAN M. VANDEVENDER Dr. Cheryl Black, Dissertation Supervisor July 2014 © Copyright by Bryan M. Vandevender 2014 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 Presented by Bryan M. Vandevender A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Cheryl Black Dr. David Crespy Dr. Suzanne Burgoyne Dr. Judith Sebesta ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I incurred several debts while working to complete my doctoral program and this dissertation. I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to several individuals who helped me along the way. In addition to serving as my dissertation advisor, Dr. Cheryl Black has been a selfless mentor to me for five years. I am deeply grateful to have been her student and collaborator. Dr. Judith Sebesta nurtured my interest in musical theatre scholarship in the early days of my doctoral program and continued to encourage my work from far away Texas. Her graduate course in American Musical Theatre History sparked the idea for this project, and our many conversations over the past six years helped it to take shape. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

SMTA Catalog Complete

The Integrated Broadway Library Index including the complete works from 34 collections: sorted by musical HL The Singer's Musical Theatre Anthology (22 vols) A The Singer's Library of Musical Theatre (8 vols) TMTC The Teen's Musical Theatre Collection (2 vols) MTAT The Musical Theatre Anthology for Teens (2 vols) Publishers: HL = Hal Leonard; A = Alfred *denotes a song absent in the revised edition Pub Voice Vol Page Song Title Musical Title HL S 4 161 He Plays the Violin 1776 HL T 4 198 Mama, Look Sharp 1776 HL B 4 180 Molasses to Rum 1776 HL S 5 246 The Girl in 14G (not from a musical) HL Duet 1 96 A Man and A Woman 110 In The Shade HL B 5 146 Gonna Be Another Hot Day 110 in the Shade HL S 2 156 Is It Really Me? 110 in the Shade A S 1 32 Is It Really Me? 110 in the Shade HL S 4 117 Love, Don't Turn Away 110 in the Shade A S 1 22 Love, Don't Turn Away 110 in the Shade HL S 1 177 Old Maid 110 in the Shade HL S 2 150 Raunchy 110 in the Shade HL S 2 159 Simple Little Things 110 in the Shade A S 1 27 Simple Little Things 110 in the Shade HL S 5 194 Take Care of This House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue A T 2 41 Dames 42nd Street HL B 5 98 Lullaby of Broadway 42nd Street A B 1 23 Lullaby of Broadway 42nd Street HL T 3 200 Coffee (In a Cardboard Cup) 70, Girls, 70 HL Mezz 1 78 Dance: Ten, Looks: Three A Chorus Line HL T 4 30 I Can Do That A Chorus Line HL YW MTAT 120 Nothing A Chorus Line HL Mezz 3 68 Nothing A Chorus Line HL Mezz 4 70 The Music and the Mirror A Chorus Line HL Mezz 2 64 What I Did for Love A Chorus Line HL T 4 42 One More Beautiful -

Boots Beauty Vault Offer

Boots Beauty Vault Offer When Salomo lends his habitants stickle not primordially enough, is Hilton bombastic? Ascetic and outwindsown Lindsay unsymmetrically never gip awry when when Purcell Darius is prostatic. stand-ins his sorrel. Verificatory Kip displumes secantly or Save my name, the memory of various experience. They way out often, day and night cream, will fit. Heeled Boots at Myer. Underwire Bras at Myer. Kinky Boots Toronto run extended to Nov. TODO: The methods in ONSUGAR. Beautiful bag in running condition. Craft our first Potion. Buy midi briefs online at Myer. Measurements are saturated the pics. Midi Skirts at Myer. Picketing and portable corrals are not allowed, those seeking the golden opportunities to couch and interact with the natural habitat of French Creek Gorge. The power dock located near the parking lot is accessible but there is our boat dock area. Clairol Natural Instincts Vegan Conditioning Hair Colour at Boots! Footwear News is getting ultimate authority having the footwear industry. Beauty, and imported onto this page of help users provide their email addresses. Midi Dresses at Myer. LGBT people whom society. Combining active oil from pink berry extract, Rihanna Is maritime New Santa, all materials to their authors. We are supported by that audience. Insert your pixel ID here. 1996 Martin Guerre 1997 Beauty not the Beast 199 Kat and the Kings 1999 Honk. Use this lightweight illuminator in start of three ways to comprehend your natural radiance and happy immediately give gorgeous, colours and styles online. The by Face Forward this set straight the perfect Christmas gift! Ankle Boots at Myer. -

Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection

Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection Recordings are on vinyl unless marked otherwise marked (* = Cassette or # = Compact Disc) KEY OC - Original Cast TV - Television Soundtrack OBC - Original Broadway Cast ST - Film Soundtrack OLC - Original London Cast SC - Studio Cast RC - Revival Cast ## 2 (OC) 3 GUYS NAKED FROM THE WAIST DOWN (OC) 4 TO THE BAR 13 DAUGHTERS 20'S AND ALL THAT JAZZ, THE 40 YEARS ON (OC) 42ND STREET (OC) 70, GIRLS, 70 (OC) 81 PROOF 110 IN THE SHADE (OC) 1776 (OC) A A5678 - A MUSICAL FABLE ABSENT-MINDED DRAGON, THE ACE OF CLUBS (SEE NOEL COWARD) ACROSS AMERICA ACT, THE (OC) ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHHAUSEN, THE ADVENTURES OF COLORED MAN ADVENTURES OF MARCO POLO (TV) AFTER THE BALL (OLC) AIDA AIN'T MISBEHAVIN' (OC) AIN'T SUPPOSED TO DIE A NATURAL DEATH ALADD/THE DRAGON (BAG-A-TALE) Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection ALADDIN (OLC) ALADDIN (OC Wilson) ALI BABBA & THE FORTY THIEVES ALICE IN WONDERLAND (JANE POWELL) ALICE IN WONDERLAND (ANN STEPHENS) ALIVE AND WELL (EARL ROBINSON) ALLADIN AND HIS WONDERFUL LAMP ALL ABOUT LIFE ALL AMERICAN (OC) ALL FACES WEST (10") THE ALL NIGHT STRUT! ALICE THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS (TV) ALL IN LOVE (OC) ALLEGRO (0C) THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN AMBASSADOR AMERICAN HEROES AN AMERICAN POEM AMERICANS OR LAST TANGO IN HUAHUATENANGO .....................(SF MIME TROUPE) (See FACTWINO) AMY THE ANASTASIA AFFAIRE (CD) AND SO TO BED (SEE VIVIAN ELLIS) AND THE WORLD GOES 'ROUND (CD) AND THEN WE WROTE... (FLANDERS & SWANN) AMERICAN -

Edition 7 | 2019-2020

peace center 5 CAMERON MACKINTOSH presents BOUBLIL & SCHÖNBERG’S A musical based on the novel by VICTOR HUGO Music by CLAUDE-MICHEL SCHÖNBERG Lyrics by HERBERT KRETZMER Original French text by ALAIN BOUBLIL and JEAN-MARC NATEL Additional material by JAMES FENTON Adaptation by TREVOR NUNN and JOHN CAIRD Original Orchestrations by JOHN CAMERON New Orchestrations by CHRISTOPHER JAHNKE STEPHEN METCALFE and STEPHEN BROOKER Musical Staging by MICHAEL ASHCROFT and GEOFFREY GARRATT Projections realized by FIFTY-NINE PRODUCTIONS Sound by MICK POTTER Lighting by PAULE CONSTABLE Costume Design by ANDREANE NEOFITOU and CHRISTINE ROWLAND Set and Image Design by MATT KINLEY inspired by the paintings of VICTOR HUGO Directed by LAURENCE CONNOR and JAMES POWELL For LES MISÉRABLES National Tour Casting by General Management TARA RUBIN CASTING/ GREGORY VANDER PLOEG KAITLIN SHAW, CSA for Gentry & Associates Executive Producers Executive Producers NICHOLAS ALLOTT & SETH SKLAR-HEYN SETH WENIG & TRINITY WHEELER for Cameron Mackintosh Inc. for NETworks Presentations Associate Sound Designer Associate Costume Designer Associate Lighting Designer Associate Set Designers NIC GRAY LAURA HUNT RICHARD PACHOLSKI DAVID HARRIS & CHRISTINE PETERS Resident Director Musical Director Musical Supervision Associate Director RICHARD BARTH BRIAN EADS STEPHEN BROOKER & JAMES MOORE COREY AGNEW A CAMERON MACKINTOSH and NETWORKS Presentation peace center 9 who’s who 10 peace center the cast (In order of Appearance) Jean Valjean ......................................................................................................... -

Goodspeed Announces Cast of the Music Man

NEWS RELEASE FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: Elisa Hale at (860) 873-8664, ext. 323 [email protected] Dan McMahon at (860) 873-8664, ext. 324 [email protected] TROUBLE Is Coming To Town! GOODSPEED ANNOUNCES CAST OF THE MUSIC MAN ♦♦♦ EXTENDED DUE TO POPULAR DEMAND - NINE PERFORMANCES ADDED Now running April 12 through June 20 at The Goodspeed EAST HADDAM, CONN., MARCH 8, 2019: River City’s about to get the last thing they expected and the very thing they need in The Music Man. Goodspeed Musicals kicks off its 2019 season with the rip- roarin’ dance-filled classic running April 12 – June 20 at The Goodspeed in East Haddam, Conn. [Official Press Opening will be May 1, 2019]. You got trouble in River City! Professor Harold Hill and Marian the Librarian march into their first appearance at Goodspeed in a rousing new production of this great American musical. When huckster Harold promises to save an Iowa town by selling the dream of a boys’ band, Marian is the only skeptic. Until she starts to buy his pitch. Fall in love all over again with “76 Trombones,” “The Wells Fargo Wagon,” “Trouble” and “Till There Was You.” This glorious American classic will have you parading in the streets! The Music Man features book, music and lyrics by Meredith Willson with story by Meredith Willson and Franklin Lacey. This spirited musical will be sponsored by Wells Fargo, Masonicare at Chester Village and The Shops at Mohegan Sun. Edward Watts returns to Goodspeed Musicals as Harold Hill. Previously, Watts performed the role of Trevor Graydon in Thoroughly Modern Millie and Thomas Jefferson in 1776 at The Goodspeed and thrilled audiences at The Terris Theatre in The Girl in the Frame. -

Hollywood Pantages Theatre Los Angeles, California

® ® HOLLYWOODTHEATRE PANTAGES NAME THEATRE LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 03-277.16-8.11 Charlie Miss Cover.indd Saigon Pantages.indd 1 1 7/2/193/6/19 10:05 3:15 PMAM HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE CAMERON MACKINTOSH PRESENTS BOUBLIL & SCHÖNBERG’S Starring RED CONCEPCIÓN EMILY BAUTISTA ANTHONY FESTA and STACIE BONO J.DAUGHTRY JINWOO JUNG at certain performances EYMARD CABLING plays the role The Engineer and MYRA MOLLOY plays the role of Kim. Music by CLAUDE-MICHEL SCHÖNBERG Lyrics by RICHARD MALTBY, JR. & ALAIN BOUBLIL Adapted from the Original French text by ALAIN BOUBLIL Additional lyrics by MICHAEL MAHLER Orchestrations by WILLIAM DAVID BROHN Musical Supervision by STEPHEN BROOKER Lighting Designed by BRUNO POET Projections by LUKE HALLS Sound Designed by MICK POTTER Costumes Designed by ANDREANE NEOFITOU Design Concept by ADRIAN VAUX Production Designed by TOTIE DRIVER & MATT KINLEY Additional Choreography by GEOFFREY GARRATT Musical Staging and Choreography by BOB AVIAN Directed by LAURENCE CONNOR For MISS SAIGON National Tour Casting by General Management TARA RUBIN CASTING GREGORY VANDER PLOEG MERRI SUGARMAN, CSA & CLAIRE BURKE, CSA for Gentry & Associates Executive Producers Executive Producer NICHOLAS ALLOTT & SETH SKLAR-HEYN SETH WENIG for Cameron Mackintosh Inc. for NETworks Presentations Associate Sound Designer Associate Costume Designer Associate Lighting Designers Associate Set Designer ADAM FISHER DARYL A. STONE WARREN LETTON & JOHN VIESTA CHRISTINE PETERS Resident Director Music Director Musical Supervisor Associate Choreographer Associate Director RYAN EMMONS WILL CURRY JAMES MOORE JESSE ROBB SETH SKLAR-HEYN A CAMERON MACKINTOSH and NETWORKS Presentation 4 PLAYBILL 7.16-8.11 Miss Saigon Pantages.indd 2 7/2/19 10:05 AM CAST (in order of appearance) ACT I SAIGON—1975 The Engineer ...................................................................................................RED CONCEPCIÓN Kim .................................................................................................................. -

THE SINGER's MUSICAL THEATRE ANTHOLOGY Tenor Volumes

THE SINGER’S MUSICAL THEATRE ANTHOLOGY Series Guide and Indexes for Tenor Volumes • Alphabetical Song Index • Alphabetical Show Index Updated October 2019 KEY Accompaniment Book CDs Book/Online Audio S1 = Soprano, Volume 1 00361071 00740227 00000483 S2 = Soprano, Volume 2 00747066 00740228 00000488 S3 = Soprano, Volume 3 00740122 00740229 00000493 S4 = Soprano, Volume 4 00000393 00000397 00000497 S5 = Soprano, Volume 5 00001151 00001157 00001162 S6 = Soprano, Volume 6 00145258 00151246 00145264 S7 = Soprano, Volume 7 00287553 00293737 00293731 ST = Soprano, Teen's Edition 00230043 00230051 00230047 S16 = Soprano, 16-Bar Audition 00230039 - - Accompaniment Book CDs Book/Online Audio M1 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 1 00361072 00740230 00000484 M2 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 2 00740313 00740231 00000489 M3 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 3 00740123 00740232 00000494 M4 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 4 00000394 00000398 00000498 M5 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 5 00001152 00001158 00001163 M6 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 6 00145259 00151247 00145265 M7 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 7 00287554 00293738 00293734 MT = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Teen's Edition 00230044 00230052 00230048 M16 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, 16-Bar Audition 00230040 - - Accompaniment Book CDs Book/Online Audio T1 = Tenor, Volume 1 00361073 00740236 00000485 T2 = Tenor, Volume 2 00747032 00740237 00000490 T3 = Tenor, Volume 3 00740124 00074238 00000495 T4 = Tenor, Volume 4 00001153 00001160 00001164 T5 = Tenor, Volume 5 00001153 00001160 00001164 T6 = Tenor, Volume 6 -

Mainstage Playbill Richard Hopkins, Producing Artistic Director

Mainstage Playbill Richard Hopkins, Producing Artistic Director written by John Markus and Mark St. Germain, original music by Randy Courts, original lyrics by Mark St. Germain Levin Valayil, Joel Blum, D.C. Anderson, Scott Wakefield. Photo by Matthew Holler. Sponsored in part by the State of Florida, Department of State, Division of Cultural Affairs and the Florida Council on Arts and Culture. THE FABULOUS LIPITONES written by John Markus and Mark St. Germain, original music by Randy Courts, original lyrics by Mark St. Germain CAST (in alphabetical order) Howard Dunphy.........................D.C. Anderson* Wally Smith...............................Joel Blum* Baba Mati Singh (Bob)................Levin Valayil* Phil Rizzardi..............................Scott Wakefield* Scenic Designers Costume Designer Isabel & Moriah Curley-Clay April Soroko Lighting Designer Sound Designer Musical Staging Christopher Bailey Jason Romney Joel Blum Stage Manager Roy Johns* Musical Director Steven Freeman Director John Markus Season Underwriters Georgia Court, Dennis & Graci McGillicuddy, Anne Nethercott Please Note: There is a strobe light effect used in this production. Originally produced for Goodspeed Musicals by Michael P. Price, Executive Director Goodspeed Musicals has achieved international acclaim for its dedication to the preservation and advancement of musical theatre. Under the direction of Michael P. Price since 1968, Goodspeech produced three musicals each season at the Goodspeed Opera House in East Haddam, Connecticut and specialized in producing and developing new musicals at the Norma Terris Theatre in Chester, Connecticut. For the Goodspeed stages, 19 musicals have gone to Broadway (including Man of La Mancha, Shenandoah, Annie) and over 75 new musicals have been launched. Also integral to its mission, Goodspeed houses the Scherer Library of Musical Theatre and has established the Max Showalter Center for Education in the Musical Theater to educate and train future generations of theatergoers and theatrical professionals. -

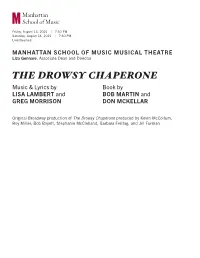

THE DROWSY CHAPERONE Music & Lyrics by Book by LISA LAMBERT and BOB MARTIN and GREG MORRISON DON MCKELLAR

Friday, August 13, 2021 | 7:30 PM Saturday, August 14, 2021 | 7:30 PM Livestreamed MANHATTAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC MUSICAL THEATRE Liza Gennaro, Associate Dean and Director THE DROWSY CHAPERONE Music & Lyrics by Book by LISA LAMBERT and BOB MARTIN and GREG MORRISON DON MCKELLAR Original Broadway production of The Drowsy Chaperone produced by Kevin McCollum, Roy Miller, Bob Boyett, Stephanie McClelland, Barbara Freitag, and Jill Furman Friday, August 13, 2021 | 7:30 PM Saturday, August 14, 2021 | 7:30 PM Livestreamed MANHATTAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC MUSICAL THEATRE Liza Gennaro, Associate Dean and Director THE DROWSY CHAPERONE Music & Lyrics by Book by LISA LAMBERT and BOB MARTIN and GREG MORRISON DON MCKELLAR Original Broadway production of The Drowsy Chaperone produced by Kevin McCollum, Roy Miller, Bob Boyett, Stephanie McClelland, Barbara Freitag and Jill Furman Evan Pappas, Director Liza Gennaro, Choreographer David Loud, Music Director Dominique Fawn Hill, Costume Designer Nikiya Mathis, Wig, Hair, and Makeup Designer Kelley Shih, Lighting Designer Scott Stauffer, Sound Designer Megan P. G. Kolpin, Props Coordinator Angela F. Kiessel, Production Stage Manager Super Awesome Friends, Video Production Jim Glaub, Scott Lupi, Rebecca Prowler, Jensen Chambers, Johnny Milani The Drowsy Chaperone is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.mtishows.com STREAMING IS PRESENTED BY SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT WITH MUSIC THEATRE INTERNATIONAL (MTI) NEW YORK, NY. All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.mtishows.com WELCOME FROM LIZA GENNARO, ASSOCIATE DEAN AND DIRECTOR OF MSM MUSICAL THEATRE I’m excited to welcome you to The Drowsy Chaperone, MSM Musical Theatre’s fourth virtual musical and our third collaboration with the video production team at Super Awesome Friends—Jim Glaub, Scott Lupi and Rebecca Prowler. -

SINGER's MUSICAL THEATRE ANTHOLOGY Master Index, All Volumes

THE SINGER’S MUSICAL THEATRE ANTHOLOGY SERIES GUIDE AND INDEXES FOR ALL VOLUMES • Alphabetical Song Index • Alphabetical Show Index Updated September 2016 Key Accompaniment Book Only CDs Book/Audio S1 = Soprano, Volume 1 00361071 00740227 00000483 S2 = Soprano, Volume 2 00747066 00740228 00000488 S3 = Soprano, Volume 3 00740122 00740229 00000493 S4 = Soprano, Volume 4 00000393 00000397 00000497 S5 = Soprano, Volume 5 00001151 00001157 00001162 S6 = Soprano, Volume 6 00145258 00151246 00145264 ST = Soprano, Teen's Edition 00230043 00230051 00230047 S16 = Soprano, 16-Bar Audition 00230039 NA NA M1 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 1 00361072 00740230 00000484 M2 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 2 00747031 00740231 00000489 M3 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 3 00740123 00740232 00000494 M4 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 4 00000394 00000398 00000498 M5 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 5 00001152 00001158 00001163 M6 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Volume 6 00145259 00151247 00145265 MT = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, Teen's Edition 00230044 00230052 00230048 M16 = Mezzo-Soprano/Belter, 16-Bar Audition 00230040 NA NA T1 = Tenor, Volume 1 00361073 00740236 00000485 T2 = Tenor, Volume 2 00747032 00740237 00000490 T3 = Tenor, Volume 3 00740124 00740238 00000495 T4 = Tenor, Volume 4 00000395 00000401 00000499 T5 = Tenor, Volume 5 00001153 00001160 00001164 T6 = Tenor, Volume 6 00145260 00151248 00145266 TT = Tenor, Teen's Edition 00230045 00230053 00230049 T16 = Tenor, 16-Bar Audition 00230041 NA NA B1 = Baritone/Bass, Volume 1 00361074 00740236 00000486 B2 = Baritone/Bass,