New Observations in the Histopathology of Erythema Nodosum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(ERYTHEMA NODOSUM LEPROSUM) the Term

? THE HISTOPATHOLOGY OF ACUTE PANNICULITIS NODOSA LEPROSA (ERYTHEMA NODOSUM LEPROSUM) w. J. PEPLER, M.B., Ch.B. Department of Pathology, South African Institute for Medical Research, Johannesburg R. KOOIJ, M.D. Westfort Institution, Pretoria AND J. MARSHALL, M.D. University of Pretoria, Pretoria The term "erythema nodosum leprosum" has frequently appeared in the literature on leprosy since the 1930's, apparently popularized by the Japanese (9). The occurrence of "erythema nodosum" in leprosy had previously been noted at the end of the nineteenth century by Brocq (6) and by Hansen and Looft (8), but the term seems to have fallen into disuse. As will become clear from our clinical and histological descriptions of the phenomenon commonly known as erythema nodosum leprosum, we believe the title to be a misnomer. We suggest that it would be more accurate to call it panniculitis nodosa leprosa (P.N.L,). This condition is commonly confused with acute lepra reaction, both processes being referred to as "acute reactions"; but a sharp line of distinction must be drawn between them. P.N.L. occurs only in patients with lepromatous leprosy as an acute, subacute or chronic skin eruption, with or without fever. It is characterized by showers of dusky red nodules, 0.5 to 2 cm. in diameter, on the extensor surfaces of the limbs, on the face, and, less often, on the trunk. The number of lesions appearing in an attack varies from a few to several hundreds, and they sometimes coalesce to form plaques. The nodules may be painful, and they are usually tender to touch. -

Chapter 3 Bacterial and Viral Infections

GBB03 10/4/06 12:20 PM Page 19 Chapter 3 Bacterial and viral infections A mighty creature is the germ gain entry into the skin via minor abrasions, or fis- Though smaller than the pachyderm sures between the toes associated with tinea pedis, His customary dwelling place and leg ulcers provide a portal of entry in many Is deep within the human race cases. A frequent predisposing factor is oedema of His childish pride he often pleases the legs, and cellulitis is a common condition in By giving people strange diseases elderly people, who often suffer from leg oedema Do you, my poppet, feel infirm? of cardiac, venous or lymphatic origin. You probably contain a germ The affected area becomes red, hot and swollen (Ogden Nash, The Germ) (Fig. 3.1), and blister formation and areas of skin necrosis may occur. The patient is pyrexial and feels unwell. Rigors may occur and, in elderly Bacterial infections people, a toxic confusional state. In presumed streptococcal cellulitis, penicillin is Streptococcal infection the treatment of choice, initially given as ben- zylpenicillin intravenously. If the leg is affected, Cellulitis bed rest is an important aspect of treatment. Where Cellulitis is a bacterial infection of subcutaneous there is extensive tissue necrosis, surgical debride- tissues that, in immunologically normal individu- ment may be necessary. als, is usually caused by Streptococcus pyogenes. A particularly severe, deep form of cellulitis, in- ‘Erysipelas’ is a term applied to superficial volving fascia and muscles, is known as ‘necrotiz- streptococcal cellulitis that has a well-demarcated ing fasciitis’. This disorder achieved notoriety a few edge. -

(Tdap) Vaccine- Related Erythema Nodosum: Case Report and Review of Vaccine-Associated Erythema Nodosum

Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) (2013) 3:191–197 DOI 10.1007/s13555-013-0035-9 CASE REPORT Combined Reduced-Antigen Content Tetanus, Diphtheria, and Acellular Pertussis (Tdap) Vaccine- Related Erythema Nodosum: Case Report and Review of Vaccine-Associated Erythema Nodosum Philip R. Cohen To view enhanced content go to www.dermtherapy-open.com Received: September 23, 2013 / Published online: November 1, 2013 Ó The Author(s) 2013. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com ABSTRACT literature search was performed on erythema nodosum, vaccine, and vaccination. Background: Vaccination programs reduce the Results: Tdap, the most commonly used booster morbidity and mortality of diphtheria, vaccine against tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis, pertussis, and tetanus. Erythema nodosum is a is well tolerated in all age groups. Local injection- reactive erythema that can be associated with site reactions are the most common adverse events, infections, drugs, and many conditions. The whereas headache, fatigue, gastrointestinal new onset of erythema nodosum after receiving symptoms, and fever are the most frequent vaccination is uncommon. systemic events. Erythema nodosum has not Purpose: Combined reduced-antigen content previously been reported in patients who have tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis received Tdap vaccine. The patient developed (Tdap) vaccine-associated erythema nodosum erythema nodosum within 48 h after receiving is described and the reports of vaccine-related Tdap vaccine; her symptoms cleared and nearly all erythema nodosum are summarized. skin lesions resolved within 2 weeks after initiating Methods: The clinical features of a 39-year-old oral treatment with ibuprofen, fexofenadine, and woman who developed erythema nodosum prednisone. Vaccine-associated erythema after receiving Tdap vaccine are reported. -

Bazin's Disease (Erythema Induratum)

Images in Rheumatology Clinical Images: Bazin’s Disease (Erythema Induratum) MANAL AL-MASHALEH, MD, JBM, Visiting Fellow, Rheumatology Department; DON PACKHAM, MBBS, FRACP, Staff Specialist, Infectious Disease Department, Westmead Hospital; NICHOLAS MANOLIOS, MBBS(Hons), MD, PhD, FRACP, FRCPA, Director of Rheumatology, Associate Professor, University of Sydney, Rheumatology Department, Westmead Hospital, Sydney, Australia. Address reprint requests to Dr. Manolios. E-mail: [email protected] Our case highlights the similarity between erythema nodosum Bazin’s disease (EI) is an under-recognized chronic recur- (EN) and erythema induratum (EI) and illustrates the impor- rent condition characterized by painless, deep-seated, subcuta- tance of Mantoux testing in investigations of patients with neous induration, which gradually extends to the skin surface, vasculitis, particularly those from tuberculous-endemic areas; forming bluish-red nodules or plaques, which then often ulcer- as well, it points to the need for biopsy if apparent EN has ate1,2. The morphologic, molecular, and clinical data suggest atypical or prolonged course or is complicated by ulceration, that EI represents a hypersensitivity reaction to tubercle bacil- and the resolution of EI with anti-TB treatment alone. lus3. As described, it is not unusual to have negative cultures A 16-year-old Indonesian girl with a 2 year history of and fail to detect M. tuberculosis by PCR amplification2,4. Sjögren’s syndrome (SSA/SSB-positive) and hepatitis C and taking no medications presented with a 2 week history of painful REFERENCES erythematous nodules over the anterior aspect of her lower limbs 1. Bayer-Garner IB, Cox MD, Scott MA, Smoller BR. -

A Cross Study of Cutaneous Tuberculosis: a Still Relevant Disease in Morocco (A Study of 146 Cases)

ISSN: 2639-4553 Madridge Journal of Case Reports and Studies Research Article Open Access A Cross study of Cutaneous Tuberculosis: A still relevant Disease in Morocco (A Study of 146 Cases) Safae Zinoune, Hannane Baybay, Ibtissam Louizi Assenhaji, Mohammed Chaouche, Zakia Douhi, Sara Elloudi, and Fatima-Zahra Mernissi Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Hassan II, Fez, Morocco Article Info Abstract *Corresponding author: Background: Burden of tuberculosis still persists in Morocco despite major advances in Safae Zinoune its treatment strategies. Cutaneous tuberculosis (CTB) is rare, and underdiagnosed, due Doctor Department of Dermatology to its clinical and histopathological polymorphism. The purpose of this multi-center Hassan II University Hospital retrospective study is to describe the epidemiological, clinical, histopathological and Fès, Morocco evolutionary aspects of CTB in Fez (Morocco). E-mail: [email protected] Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional descriptive multicenter study from May 2006 Received: March 12, 2019 to May 2016. The study was performed in the department of dermatology at the Accepted: March 18, 2019 University Hospital Hassan II and at diagnosis centers of tuberculosis and respiratory Published: March 22, 2019 diseases of Fez (Morocco). The patients with CTB confirmed by histological and/or biological examination were included in the study. Citation: Zinoune S, Baybay H, Assenhaji LI, et al. A Cross study of Cutaneous Tuberculosis: Results: 146 cases of CTB were identified. Men accounted for 39.8% of the cases (58 A still relevant Disease in Morocco (A Study of 146 Cases). Madridge J Case Rep Stud. 2019; patients) and women 60.2% (88 cases), sex-ratio was 0.65 (M/W). -

CSI Dermatology

Meagen M. McCusker, MD [email protected] Integrated Dermatology, Enfield, CT AbbVie - Speaker Case-based scenarios, using look-alike photos, comparing the dermatologic manifestations of systemic disease to dermatologic disease. Select the clinical photo that best matches the clinical vignette. Review the skin findings that help differentiate the two cases. Review etiology/pathogenesis when understood and discuss treatments. Case 1: Scaly Serpiginous Eruption This patient was evaluated for a progressively worsening pruritic rash associated with dyspnea on exertion and 5-kg weight loss. Despite its dramatic appearance, the patient reported no itch. KOH examination is negative (But, who’s good at those anyway?) A. B. Case 1: Scaly Serpiginous Eruption This patient was evaluated for a progressively worsening pruritic rash associated with dyspnea on exertion and 5-kg weight loss. Despite its dramatic appearance, the patient reported no itch. KOH examination is negative (But, who’s good at those anyway?) A. Correct. B. Tinea Corporis Erythema Gyratum Repens Erythema Gyratum Repens Tinea corporis Rare paraneoplastic T. rubrum > T. mentagrophytes phenomenon typically > M. canis associated with lung Risk factors cancer>esophageal and breast Close contact, previous cancers. infection, Less commonly associated with occupational/recreational connective tissue disorders such exposure, contaminated as Lupus or Rheumatoid furniture or clothing, Arthritis gymnasium, locker rooms “Figurate erythema” migrates up 1-3 week incubation → to 1 cm a day centrifugal spread from point of Resolves with treatment of the invasion with central clearing malignancy This patient was diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Case 2: Purpuric Eruption on the Legs & Buttocks A 12-year old boy presents with a recent history of upper respiratory tract infection, fever and malaise. -

Port Site Tuberculous Infection a Case Report and Review of Literature

IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) e-ISSN: 2279-0853, p-ISSN: 2279-0861.Volume 15, Issue 5 Ver. IX (May. 2016), PP 45-48 www.iosrjournals.org Port Site Tuberculous Infection a Case Report and Review of Literature Prof.N.Tamilselvan1 MS, Dr.P.V.Dhanapal2 MS 1(Associate Professor, Department of General Surgery, Government Mohan Kumaramangalam Medical College, Salem) 2(Senior Assistant Professor, Department of General Surgery, Government Mohan Kumaramangalam Medical College, Salem) Abstract: As the surgeries done by laparoscopy are increasing, associated complications are also increasing. One among them is port site infection especially port site infections due to Atypical Mycobacteriae .There is a concern about the effectiveness of sterilizing reusable laparoscopic instruments which might be a potential source of these infections, if not properly sterilized. Here we present a case report of port site tuberculosis following laparoscopic appendicectomy which was managed effectively by surgery and anti tubercular drugs. Keywords: Atypical mycobacteria,Non-healing sinus, Port site infection, Sterilization, I. Introduction Atypical mycobacteria are acid-fast bacilli that do not cause tuberculosis or leprosy. These atypical mycobacteria exist in almost all habitats. They cause a variety of clinical problems, there are about 110 species of atypical mycobacteria of which the Mycobacterium avium complex is the most common organism that causes systemic disease in humans. The most common infection is the so-called fish tank granuloma, which is caused by Mycobacterium marinum. Sometimes these organisms gain entry in to the body through pinprick or thorn prick. These infections may be preceded by surgeries like cosmetic liposuction, liposculpture, augmentation mammoplasty, or median sternotomy. -

International Journal of .Leprosy

• , I ", , . I INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF .LEPROSY VOLUME 25, NUMBER 4 OCTOBER-DECEMBER, 1957 ERYiTMA INDURATUM LEPROSUM, A DEEP NODULAR FORMY OF REACTION IN LEPROMATOUS LEPROSY JOSE N. RODRIGUEZ, M.D. '.... Chief. Division of SanitOlria Bureau of Hospitals. Department of Health. Manila One of the more noticeable effects of the sulfone treatment of leprosy, as seen among the patients at the Central Luzon Sanitarium, is the increase of frequency of erythema nodosum leprosum and also an ap parent modification of the course of that condition in some cases. Among a group of moderately and markedly advanced lepromatous cases dealt with in this report, 83 per cent developed acute lepra reaction, chiefly of the erythema nodosum type, over a period of 2 years under sulfone treatment. With so many cases of reactions to observe, and with re awakened interest in these acute skin manifestations of the lepromatous type, it has been surprising to discover how many interesting features of this familiar phenomenon we have glossed over or missed in the past. No attempt will be made here to describe in detail the manifestations of typical erythema nodosum leprosum. This article deals only with a certain heretofore little-noticed phase of both the acute and the recurrent forms of lepra reaction in lepromatous leprosy, here called "erythema induratum leprosum." This form of reaction is characterized by acute, deep-seated subcutaneous nodules and chronic fibrous masses called by our patients tolondron, a Spanish word meaning contusion or bump. The histology of these nodules during their various stages suggests that they may occupy a unique place in the unfolding of the infection in the skin in the lepromatous type of the disease. -

Cutaneous Tuberculosis Epidemiology

Cutaneous tuberculosis Epidemiology Cutaneous tuberculosis occurs worldwide; incidence of different forms varies globally. India: Affected 2% of all skin outpatients (1950s and 1960s) and then 0.1% by 1980s; due to the availability of effective drugs and improvement in the living standards. In India, scrofuloderma is common in children; lupus vulgaris commonest in adults. Resurgence in tuberculosis, and consequently in cutaneous tuberculosis; due to the HIV pandemic, resistant strains of M. tuberculosis, use of immunosuppressive therapy, ease of global travel and migration, poverty, malnutrition. Aetiology Caused by M. tuberculosis, M. bovis and under certain conditions, the bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), an attenuated strain of M. bovis. M. tuberculosis and M. bovis cause identical skin manifestations in humans. In HIV-infected individuals, even atypical saprophytic strains of Mycobacterium may cause infection and bizarre forms of disease. Cutaneous tuberculosis Spectrum of cutaneous changes induced by M. tuberculosis depend upon: ◦ Route of infection ◦ Immunological state of the host Mere presence of mycobacteria in the skin does not lead to the clinical disease. Routes of infection Exogenous ◦ From an external source, through breach in the skin at the site of trauma. Endogenous ◦ Through contiguous involvement of skin ◦ Through lymphatic spread ◦ Through haematogenous dissemination Autoinoculation Classification (Modified from Beyt et al.) Inoculation tuberculosis (exogenous source) Secondary tuberculosis (endogenous -

Disseminated Erythema Induratum in a Patient with a History of Tuberculosis

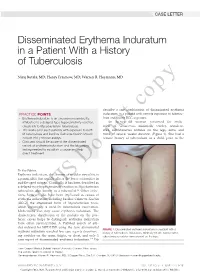

CASE LETTER Disseminated Erythema Induratum in a Patient With a History of Tuberculosis Niraj Butala, MD; Henry Fraimow, MD; Warren R. Heymann, MD copy describe a rare combination of disseminated erythema PRACTICE POINTS induratum in a patient with remote exposure to tubercu- • Erythema induratum is an uncommon panniculitis losis and recent BCG exposure. attributed to a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction, An 88-year-old woman presented for evalu- classically to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. ation of violaceous, minimally tender, nonulcer- • The workup for such patients with exposure to both ated, subcutaneous nodules on the legs, arms, and M tuberculosis and bacillus Calmette-Guérin should trunk of several weeks’ duration (Figure 1). She had a include IFN-γ release assays. remotenot history of tuberculosis as a child, prior to the • Clinicians should be aware of the disseminated variant of erythema induratum and the laboratory testing needed to establish a cause and help direct treatment. Do To the Editor: Erythema induratum, also known as nodular vasculitis, is a panniculitis that usually affects the lower extremities in middle-aged women. Classically, it has been described as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, also known as a tuberculid.1,2 Other infec- tions, however, also have been implicated as causes of erythema induratum, including bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), the attenuated form of Mycobacterium bovis, which commonly is used for tuberculosis vaccination. Medications also may cause erythema induratum. The characteristicCUTIS distribution of the nodules on the pos- terior calves helps to distinguish erythema induratum from other panniculitides. A PubMed search of arti- cles indexed for MEDLINE using the term disseminated FIGURE 1. -

Original Article Cutaneous Manifestations of Extra Pulmonary

Original Article Cutaneous Manifestations of Extra pulmonary Tuberculosis Ahmad S1, Ahmed N2, Singha JL3, Mamun MAA4, Hassan ASMFU5, Aziz NMSB6, Alam SI7 Conflict of Interest: None Abstract: Received: 12-08-2018 Background: Ulcers and surgical wounds not healing well and expectedly are common problems Accepted: 06-11-2018 www.banglajol.info/index.php/JSSMC among patients in countries like us. Ulcers may develop spontaneously or following a penetrating injury. wounds not healing well are common among poor, lower middle class and middle class people. Postsurgical non-healing wound or chronic discharging sinuses at the scar site are also common in that class of people. Suspecting malignancy or tuberculosis in these types of wounds we have sent wedge or excision biopsy for these ulcers in about 500 cases and found tuberculosis in 65 cases. In rest of the cases histopathology reports found as non- specific ulcers, Malignant melanoma, squamous or basal cell carcinoma, Verruca vulgaris. Objectives: To find out the relationship of tuberculosis with chronic or nonhealing ulcers. Methods: This is a prospective observational study conducted for patients coming to our chambers, OPD of a district general hospital and Shaheed Suhrawardy Medical College Hospital, Dhaka from July 2012 to June 2018. Results: Mean age of the study subjects were 28±2. Among the study subjects nonspecific ulcer or sinus tracts were found in 418 (83.6%), tuberculosis in 65 (13%), Malignant melanoma 7 (1.4%), Verruca vulgaris 5(1%), squamous cell carcinoma 3(0.6), basal cell carcinoma 2 (0.4%). Biopsy done only for very suspicious ulcers or wounds. Key Words: Cutaneous Conclusion: With this very small sample size it is difficult to conclude regarding incidence of manifestation, Extrapulmonary cutaneous involvement of extra pulmonary tuberculosis , but every clinician should think of it in case involvement, Tuberculosis. -

Computer Diagnosis of Skin Disease

COMPUTERS IN FAMILY PRACTICE Computer Diagnosis of Skin Disease Brian Potter, MD, and Salve G. Ronan, MD Michigan City, Indiana, and Chicago, Illinois A transferable computer program for the differential diagnosis of diseases of the skin, CLINDERM, has been produced for use by physicians on standard IBM and compat ible personal microcomputers. This program lists the differential diagnosis and defini tive diagnosis of any presented disease of the skin, except single tumors. The physi cian operator indicates the distribution and detailed description of lesions, which the interactive system integrates with a comprehensive knowledge base. The computer diagnosis in 129 cases was compared with independent interpreta tion of the same information by an academic dermatologist. Results were synony mous in 66.7% of all diseases and similar in an additional 4.7%. A common differen tial diagnosis was obtained in 24%, for a 95.3% rate of synonymous, similar, or common differential diagnoses. Diagnosis was different in 3.9% and description was inadequate for diagnosis in 0.8%. The variation in diagnosis showed that some descriptive terms are prejudicial of certain diagnoses; that diagnostic terms are not all completely standardized; that some diagnoses are variants of another disease; and that drug-induced eruptions simulate many other diseases. A skin disease can usually be diagnosed by specific description. Most lesions that are not diagnostic from inspection are nodular. A computer can be programmed to list diagnoses according to morphologic description J Fam Pract 1990; 30:201-210. functional, transferable computer software system examination may, however, be excessively complex. Ob Afor the differential diagnosis of diseases of the skin, jectivity is improved by recording specific features ac called CLINDERM,* has been produced for use by phy cording to sets of standardized criteria.