Why Is There a Columbus Monument in Barcelona?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplementary Table 1

SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX Recurrent presence of the PLCG1 S345F mutation in nodal peripheral T-cell lymphomas Rebeca Manso, 1# Socorro M. Rodríguez-Pinilla, 1# Julia González-Rincón, 2 Sagrario Gómez, 2 Silvia Monsalvo, 3 Pilar Llamas, 3 Federico Rojo, 1 David Pérez-Callejo, 2 Laura Cereceda, 4 Miguel A. Limeres, 5 Carmen Maeso, 6 Lucía Ferrando, 7 Carlos Pérez-Seoane, 8 Guillermo Rodríguez, 8 José M. Arrinda, 9 Federico García-Bragado, 10 Renato Franco, 11 José L. Rodriguez-Peralto, 12 Joaquin González-Carreró, 13 Francisco Martín- Dávila, 14 Miguel A. Piris, 4* and Margarita Sánchez-Beato 2* #RM and SMR-P contributed equally to this manuscript. *Senior authors. 1Pathology Department, IIS-Fundación Jiménez Díaz, UAM, Madrid, Spain; 2Group of Research in Lymphoma, (Medical Oncology Service), Oncohematol - ogy Area, IIS Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda (IDIPHIM), Madrid, Spain; 3Haematology Department, IIS-Fundación Jiménez Díaz, UAM, Madrid, Spain; 4Pathology Department, Hospital U. Marqués de Valdecilla, IDIVAL, Santander, Spain; 5Pathology Department, Hospital U. Canarias Dr. Negrín, Gran Canaria, Canarias, Spain; 6Pathology Department, CMI Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria, Sta. Cruz de Tenerife, Spain; 7Pathology De - partment, Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara, Cáceres, Spain; 8Pathology Department, Hospital Reina Sofía, Córdoba, Spain; 9Pathology Department, Hospital del Bidasoa, Guipúzcoa, Spain; 10 Pathology Department, Hospital Virgen del Camino, Pamplona, Spain; 11 Pathology Department, Istituto Nazionale Tumori IRCSS – Fondazione Pascal, Napoli, Italy; 12 Pathology Department, Hospital U. 12 de octubre, Madrid, Spain; 13 Pathology Department, Complejo Hospita - lario U. de Vigo, Pontevedra, Spain; 14 Pathology Department, Hospital General de Ciudad Real, Spain. Correspondence: [email protected] doi:10.3324/haematol.2014.113696 Recurrent presence of the PLCG1 S345F mutation in Nodal Peripheral T- Cell Lymphomas. -

Estación Abando Indalecio Prieto Bilbao GPS: N 43˚ 15' 36" / O 2˚ 55' 41" SITUACIÓN EN LA CIUDAD

Estación de Pontevedra Pontevedra Estación de Pontevedra Pontevedra PLAZA CIRCULAR - BIRIBILA, 2. 48008 BILBAO Estación Abando Indalecio Prieto Bilbao GPS: N 43˚ 15' 36" / O 2˚ 55' 41" SITUACIÓN EN LA CIUDAD REGALOS REGALOS REGALOS 22 CORONEL TAPIOCA (PROX. APERTURA) 24 TAQUILLAS CERCANÍAS 1 LOKUM - GOLOSINAS 15 ATHLETIC CLUB 34 SERVICIOS 25 HABLAMOS TELEFONÍA 33 INFORMACIÓN, VENTA BILLETES 3 ESTANCO 26 RECUERDOS ESCANDÓN 4 COMM CENTER OSABA 6 SABIN FLORISTERÍA 12 PERFUMERÍA ARKEL Museo Guggenheim Palacio Euskalduna 16 BI-636 Estadio 15 14 San Mamés 35 34 13 ESTACIÓN BILBAO ABANDO 20 Casco Viejo 17 Parque de Miribilla 19 18 flo LÍNEA FERROCARRIL CONVENCIONAL LÍNEA FERROCARRIL SUBTERRÁNEA ACCESIBILIDAD PMR - PLANTA 0 16 15 14 35 34 13 20 17 19 18 PLATAFORMA PMR Y WC PMR 6 4 5 7 6 8 05 SERVICIOS 24 INFORMACIÓN, VENTA BILLETES 4 5 9 10 7 11 3 2 8 12 17 9 10 18 16 13 11 19 3 2 20 12 15 17 1 18 16 13 14 19 20 22 21 15 23 1 24 14 22 21 25 23 24 26 27 25 28 26 27 28 Estación de Pontevedra Pontevedra Estación de Pontevedra Pontevedra PLAZA CIRCULAR - BIRIBILA, 2. 48008 BILBAO Estación Abando Indalecio Prieto Bilbao GPS: N 43˚ 15' 36" / O 2˚ 55' 41" PLANO DE ZONA REGALOS REGALOS REGALOS 22 CORONEL TAPIOCA (PROX. APERTURA) 24 TAQUILLAS CERCANÍAS 1 LOKUM - GOLOSINAS 15 ATHLETIC CLUB 34 SERVICIOS SERVICIOS ESTACIÓN SERVICIOS EXTERIORES 25 HABLAMOS TELEFONÍA 33 INFORMACIÓN, VENTA BILLETES 3 ESTANCO 26 RECUERDOS ESCANDÓN 4 COMM CENTER OSABA 6 SABIN FLORISTERÍA 12 PERFUMERÍA ARKEL Bus Autobúses 5, 33, 56, 82, 108 Taxis Taxis Parking Parking PMR Cercanias 16 15 14 35 34 13 20 17 19 18 ACCESIBILIDAD PMR - PLANTA 0 16 15 14 35 34 13 20 17 19 18 PLATAFORMA PMR Y WC PMR 6 4 5 7 6 8 05 SERVICIOS 24 INFORMACIÓN, VENTA BILLETES 4 5 9 10 7 11 3 2 8 12 17 9 10 18 16 13 11 19 3 2 20 12 15 17 1 18 16 13 14 19 20 22 21 15 23 1 24 14 22 21 25 23 24 26 27 25 28 26 27 28 Estación de Pontevedra Pontevedra Estación de Pontevedra Pontevedra PLAZA CIRCULAR - BIRIBILA, 2. -

Direcciones Provinciales Y Consejerías De Educación En Las Cc. Aa

MINISTERIO DE EDUCACIÓN Y FORMACIÓN PROFESIONAL DIRECCIONES PROVINCIALES Y CONSEJERÍAS DE EDUCACIÓN EN LAS CC. AA. UNIDADES DE BECAS NO UNIVERSITARIAS ANDALUCÍA CONSEJERÍA DE EDUCACIÓN DELEGACIÓN PROVINCIAL DE ALMERÍA Pº. de la Caridad, 125 - Finca Sta. Isabel 04008- ALMERÍA TFNO.: 950.00.45.81/2/3 Fax 950.00.45.75 [email protected] CÁDIZ c/ Isabel la Católica, 8 11004- CÁDIZ TFNO.: 956.90.46.50 Fax 956.22.98.84 [email protected] CÓRDOBA C/Tomás de Aquino, 1-2ª - Edif.Servicios Múltiples 14071- CÓRDOBA TFNO.: 957.00.12.05 Fax 957.00.12.60 [email protected] GRANADA C/ Gran Vía de Colón, 54-56 18010- GRANADA TFNO.: 958.02.90.86/87 Fax 958.02.90.76 [email protected] HUELVA C/ Los Mozárabes, 8 21002- HUELVA TFNO.: 959.00.41.15/16 Fax 959.00.41.12 [email protected] JAÉN C/ Martinez Montañés, 8 23007- JAÉN TFNO.: 953.00.37.59/60 Fax 953.00.38.06 [email protected] 1 MÁLAGA Avda. Aurora, 47 Edf.Serv.Múltiples 29071- MÁLAGA TFNO.: 951.03.80.07/9/10 Fax 951.03.80.23 [email protected] SEVILLA Ronda del Tamarguillo, s/n 41005- SEVILLA TFNO.: 955.03.42.11 - 12 Fax 955.03.43.04 [email protected] ARAGÓN GOBIERNO DE ARAGÓN CONSEJERÍA DE EDUCACIÓN, UNIVERSIDAD, CULT. Y DEP. SERVICIO PROVINCIAL DE HUESCA Plaza de Cervantes, 2 - 2ª planta 22003- HUESCA TFNO.: 974.29.32.83 Fax 974.29.32.90 [email protected] TERUEL San Vicente de Paul, 3 44002- TERUEL TFNO.: 978.64.12.40 Fax 978.64.12.68 [email protected] ZARAGOZA Becas no universitarias C/ Juan Pablo II, 20 50009- ZARAGOZA TFNO.: 976.71.64.30 [email protected] 2 ASTURIAS GOBIERNO DEL PRINCIPADO DE ASTURIAS CONSEJERÍA DE EDUCACIÓN, CULTURA Y DEPORTE OVIEDO Plaza de España, 5 33007- OVIEDO TFNO.: 985.10.86.54 Fax 985.10.86.20 [email protected] ILLES BALEARS GOVERN DE LES ILLES BALEARS CONSELLERÍA DE EDUCACIÓN Y UNIVERSIDAD PALMA DE MALLORCA C/ del Ter, 16 - Edif. -

Geological Antecedents of the Rias Baixas (Galicia, Northwest Iberian Peninsula)

Journal of Marine Systems 54 (2005) 195–207 www.elsevier.com/locate/jmarsys Geological antecedents of the Rias Baixas (Galicia, northwest Iberian Peninsula) G. Me´ndez*, F. Vilas Grupo de Geologı´a Marina, EX1, de la Universidad de Vigo, Spain Departamento de Geociencias Marinas y Ordenacio´n del Territorio, Universidad de Vigo, 36200 Vigo, Spain Received 19 March 2003; accepted 1 July 2004 Available online 7 October 2004 Abstract The present paper reviews the current state of knowledge regarding the geology of the Rias Baixas (Galicia, northwest Iberian Peninsula), focusing specifically on characterisation, geometry, and evolution of the sedimentary bodies; physical and geological description; drainage patterns; and advances in palaeoceanography and palaeoecology. D 2004 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Rias; Galicia; Coast; Geology 1. Introduction date. However, the scientific discourse then began to question whether the Galician rias, given their variety The current state of knowledge regarding the of origins, should be truly considered rias at all. In geology of the Rias Baixas, in the northwestern recent years, research has generally focused on Spanish region of Galicia, is a consequence of an determining their Quaternary evolution, establishing extensive and fruitful research process, with roots links with global processes and characterising the based on Von Richthofen’s proposal (1886) to use the local processes. Moreover, a major line of debate has term ria to designate a type of coastline characterised centered on characterising the so-called Rias Coast, by the existence of a valley occupied by the sea, and establishing a clear distinction between the geological taking as its prototype the Galician rias. -

CENTRO HOPITALARIO MUNICIPIO PROVINCIA CCAA Hospital Jerez Puerta Del Sur Jerez De La Frontera Cádiz Andalucía Hospital San Ju

CENTRO HOPITALARIO MUNICIPIO PROVINCIA CCAA Hospital Jerez Puerta del Sur Jerez de la Frontera Cádiz Andalucía Hospital San Juan Grande Jerez de la Frontera Cádiz Andalucía Hospital San Juan de Dios Córdoba Córdoba Andalucía Hospital Costa del Sol Marbella Málaga Andalucía Clínica Parque San Antonio Málaga Málaga Andalucía Hospital de Benalmádena Xanit, S.L Benalmadena Málaga Andalucía Clínica Esperanza de Triana Sevilla Sevilla Andalucía Clínica MQ Montpellier Zaragoza Zaragoza Aragón Clínica Montecanal Zaragoza Zaragoza Aragón Clínica MAZ Zaragoza Zaragoza Aragón Servicio Aragonés de Salud Aragón Centro de diagnóstico Mansilla Albacete Albacete C. La Mancha Clínica Mompía, S.A.U Mompía Cantabria Cantabria Centro Hospitalario Padre Menni Santander Santander Cantabria Complejo Asistencial de Soria Soria Soria Castilla Y León Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid Valladolid Valladolid Castilla Y León Hospital Recoletas Castilla y León Valladolid Valladolid Castilla Y León Salud Castilla y León Castilla y León VHIO - Vall d'Hebron Instituto de Oncología Barcelona Barcelona Cataluña Consorci Sanitari Integral-Hospital Moisés Broggi Sant Joan Despí Barcelona Cataluña Fundació de Gestió Sanitaria de Santa Creu i Sant Pau Barcelona Barcelona Cataluña Fundació Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebrón Institut de Recerca Barcelona Barcelona Cataluña Hospital Clinic Barcelona Barcelona Cataluña Hospital Sant Joan de Dèu Esplugues de Llobregat Barcelona Cataluña Orden Hospitalaria de San Juan de Dios Provincia de Aragón-San RafaelSant Boi de -

I.° EXTENSION SUPERFICIAL DE GALICIA A.° HABITANTES

i.° EXTENSION SUPERFICIAL DE GALICIA Galicia, regián muy bien caracterizada, está situada en el extre- mo NO. de España, siendo su límite Sur a los 4i° 4^", en el término de Feces de Abajo, provincia de Orense, y su límite Norte, en la Estaca de Vares, provincia de La Coruña, a los 43 4$" ^ ambos de latitud Nor- te. Sus límites Oeste de Madrid están situados a los 3° 4", en el monte de San Gil, término de Casago, provincia dé Orense, y a los 5° 36", en el cabo de Toriñana, provincia de La Coruña. Tiene una extensión superficial de 29. i 5q. kilómetros cuadrados, equivalentes a 2.915•4^ hectáre^s. La extensión de cada una de las cuatro provincias es la siguient^ : Kilóm¢tros cuadradae iieetdreae Lugo ................................................... g.óĉo 98á.000 La Coruña .......................................... 9•903 790•3^ Orense ................................................ 6.q8o 6gs.ooo Pontevedra .......................................... 4•391 439•I^ ^rOTAL .............................. 29.154 z•915•400 Como puede apreciarse, Lugo es la mayor, y tiene doble superficie que Pontevedra, que es la menor. Con respecto a España, es la diecisie- teava parte de la superficie, sin incluir Baleares ni Canarias. a.° HABITANTES El censo oficial vigente, algo inferior a la realidad actual, pues es de i93o, da un total a Galicia de 2.2i4.2Y9 habitantes. Cada una de las cuatro provincias gallegas tiene el censo siguiente: Nabtrantee . Dor kIIómNro ^ Dor heetdrea La Coruña ..................................... 733•7^ 92.$4 0.92 f.ugo .............................................. 483•439 49.33 0.49 Orense ...' ........................................ 4^•^ ÓO, I I O,ÚO Pontevedra ..................................... 577•000 t31,^0 I,37 TOTAL .. -

Mondariz - Vigo - Santiago a Brief History of Galicia’S Edwardian Tourist Boom Booth Line

Mondariz - Vigo - Santiago a brief history of galicia’s Edwardian tourist boom Booth Line. r.M.S. antony Mondariz - Vigo - Santiago a brief history of galicia’s Edwardian tourist boom KIRSTY HOOPER Edita Fundación Mondariz Balneario Dirección editorial Sonia Montero Barros Texto Kirsty Hooper Realización editorial Publitia Imágenes XXXXXX I.S.B.N. 978-XXXXXXX Depósito Legal X-XXX-2013 Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra mediante impresión, fotocopia, microfilm o cualquier otro sistema, sin permiso por escrito del autor. DRAFT Prologue to Mondariz, Vigo, Santiago. this delightful book gives a wonderful insight into the Edwardian tourist industry and the early promotion of the treasures of galicia in Britain. it points not only to the wonderful cultural and natural heritage on offer but emphasises the quality of the experience and in particular the hospitality received by visitors to Mondariz. Wind the clock forward one hundred years or so and we find the treasures are still ex- tant though the competition for tourism has increased substantially across the globe. From my own experience a recent stay at Balneario de Mondariz perfectly encapsulates all the favourable comments reflected in this book. the conservation of the cultural and natural heritage is of fundamental importance to the well-being of society. the national trust in England, Wales and northern ireland, a non-governmental organisation founded in 1895, is an exemplar in this respect, having today over 4 million members and employing 6000 staff and over 70,000 volunteers. its properties receive over 19 million visitors each year. in galicia the beginnings of such an organisation, in this case tesouros de galicia, is a brilliant and much needed concept and the hope is that, in time, it will spread to the whole of Spain. -

The Story of Pontevedra

THE STORY OF PONTEVEDRA CASE STUDY #13 Thanks to decentralised composting the province of Pontevedra went from providing no options for bio-waste to a comprehensive and community-based system. After 3 years, already more than 2,000 tonnes of biowaste were locally composted and the project rolled- out in more than two-third of the province’s municipalities. Spain is still lagging behind regarding broader EU waste management objec- tives, but the story of Pontevedra proves that good results can easily be achieved with low-key and cost efficient measures. INTRODUCTION in the region. Taking into account The objective was not only to shift that of the 348 kilograms of waste away from burning or landfilling Today, the concept of a circular produced by inhabitants each and towards composting instead, economy is becoming ever more year, 53% to 55% is biowaste (45% but it was designed to create a present in European societies being food scraps and 8 to 11% decentralised, community-led sys- and with this, there is increasing being garden waste), the project tem of bio-waste management. recognition regarding the crucial was therefore designed to set- In the long term this has resulted role that composting of biowaste up a sustainable, local and cost- in a more cost-effective and can play in closing the material and efficient management system for environmentally friendly system resource loop within our economies. bio-waste. that directly benefits the local Much of the progress that is being community. made on this topic throughout After 3 years, the Revitaliza project Europe has not reached Spain yet. -

Autopista Del Atlántico AP-9

Autopista del Atlántico AP-9 Presentación del nuevo esquema de descuentos para la infraestructura gallega. 26/07/2021 El Real Decreto 1733/2011 Se abren dos tramos: uno 3º Y 4º PRÓRROGA: entre Guísamo y Santiago El Estado Acuerdo para el aumento de Norte y otro entre rescata a Se prorroga otros 25 capacidad de dos tramos y Pontevedra y Vigo. Audasa años la concesión: ampliación del Puente de suma 75 años Rande con cargo a tarifas. 17 Agosto 1973 1977 1994 30/10/2003 2013 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1979-1981 1983 2000 2011 1º PRÓRROGA: Se prorroga 1 año y 94 días PRIVATIZACIÓN la adjudicación por el R.D. 2808/1977. Real Decreto 104/2013 Adjudicación a Audasa 2º PRÓRROGA: Gratuidad el viaje de regreso de la construcción y en la provincia de Se extiende 9 años y 271 días explotación de la Pontevedra, con cargo a la concesión por el R.D. autopista por 39 años. tarifas de toda la autopista. 1809/1994. 3 Autopistas de peaje estatales 4 Real Decreto de bonificación de peajes Potenciales beneficiarios 15 millones De trayectos anuales se verán beneficiados por estas bonificaciones (peajes reducidos o gratuitos). 6 ¿Cómo son los descuentos? Vuelta gratis Descuento del 100% en todos los trayectos de vuelta que realicen vehículos ligeros en un plazo máximo de 24 horas ü La bonificación del 100% se aplica en los recorridos de regreso con el mismo origen y destino que el de ida en sentido contrario. ü Todos los días la semana, festivos incluidos. -

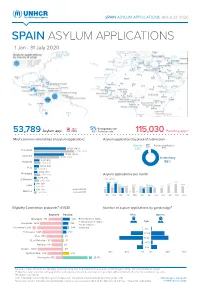

SPAIN ASYLUM APPLICATIONS JAN-JULY 2020 SPAIN ASYLUM APPLICATIONS 1 Jan - 31 July 2020

https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5226 https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5226 https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5226 https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5226 SPAIN ASYLUM APPLICATIONS JAN-JULY 2020 SPAIN ASYLUM APPLICATIONS 1 Jan - 31 July 2020 18% 5% Recognition rate 53,789 Asylum app. Dif. 2019 52% Protection rate1 115,030 Pending app.2 Most common nationalities of asylum applications Asylum applications by place of submission CIE³ Border 1.2% Family reunification 18,326 (34%) 2.8% 0.1% Venezuela 23,102 (35%) 17,206 (32%) Colombia 14,503 (22%) In territory 3,271 (6%) Honduras 3,818 (6%) 96% 2,989 (6%) Peru 1,822 (3%) 2,052 (4%) Nicaragua 3,673 (6%) Asylum applications per month 1,685 (3%) 2 0 19 2020 El Salvador 2,856 (4%) 14,633 14,484 14,143 8 0 1 ( 1%) 11,384 10 , 7 19 10,709 10,029 10,722 Cuba 9,266 682 (1%) 8 , 119 9,258 8,902 9,174 8,414 6,644 7,249 8,074 679 (1%) Jan-Jul 2020 Morocco 1, 6 6 1 ( 3 %) Jan-Jul 2019 58 72 Jan Fe b Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Eligibility Commission proposals⁴: 61,538 Number of asylum applications by gender/age⁵ Rejected Positive Men Women Geneva Conv. Status El Salvador 2,058 267 Nicaragua 770 439 Geneva Conv. Status Subsidiary Prot. Status Age Honduras 930 239Honduras 1,280 355 Subsidiary Prot. Status Hum. Reasons Morocco 372Colombia195 17,242 384 Hum. -

La Ministra De Fomento Presenta El Nuevo Tren Alvia Híbrido De Alta Velocidad De Renfe Que Unirá Galicia Y Madrid

En servicio a partir del 17 de junio La ministra de Fomento presenta el nuevo tren Alvia híbrido de alta velocidad de Renfe que unirá Galicia y Madrid • El tiempo de viaje con la capital de España se reduce más de 30 minutos y con Alicante se verá recortado en más de 2 horas • Los precios de los billetes serán los mismos que los del actual servicio • En la fabricación de los trenes, Serie 730, en la que han rensa participado Talgo y Bombardier, se ha invertido un total de 78 p millones de euros Santiago, 9 de junio de 2012. La ministra de Fomento, Ana Pastor, ha presentado hoy los nuevos trenes Alvia “híbridos-duales” de Renfe de la serie 730 entre Galicia y Madrid (los fines de semana continúan a Alicante). Los nuevos trenes híbridos-duales S-730, que sustituirán a los Talgo actuales, permitirán extender los beneficios de la alta velocidad a Nota de tramos de vía no electrificados, lo que supondrá una reducción de los tiempos de viaje de más de 30 minutos entre las dos comunidades. Reducción de tiempos Los trenes Alvia entre Madrid y Galicia recortarán significativamente su tiempo de viaje, lo que les hará más competitivos con la carretera: • Madrid-Zamora: 2 horas (actual 2.24) • Madrid-Ourense: 4 horas y 48 minutos (actual 5.20) • Madrid-Santiago: 5 horas y 36 minutos (actual 6.07) • Madrid-A Coruña: 6 horas y 9 minutos (actual 6.40) • Madrid-Vigo: 6 horas y 22 minutos (actual: 7.15) Esta información puede ser utilizada en su integridad o en parte sin necesidad de citar fuentes. -

Experience the Region of Pontevedra 08 an Artistic Treasure

EXPERIENCE THE REGION OF PONTEVEDRA 08 AN ARTISTIC TREASURE Stroll around the town of Pontevedra and be immersed in its art and history. The streets and squares are adorned with century-old granite, with medieval manor houses and churches that embellish the town. Visit its interesting museums and explore its surroundings, discover pazos and monasteries and follow the traces of petroglyphs in natural landscapes of great beauty. Discover the region of Pontevedra, an artistic treasure that comprises the towns of Pontevedra, Campo Lameiro, Barro, Poio, Vilaboa, Ponte Caldelas and A Lama. Pontevedra is full of art in every corner. The squares and streets of the old town remind us of a medieval past, in which the Pilgrim's Way to Santiago de Compostela was a very important meeting point. The Provincial Museum of Pontevedra houses archaeological, artistic and ethnographic collections of great value and invites us on a journey through the history of the province from Prehistory until the present time. 1 - A Lama 2 - Ponte Caldelas The city of Pontevedra boasts even more treasures, such as the 3 - Vilaboa remains of the ancient archiepiscopal towers, the monastery of San 4 - Pontevedra Salvador de Lérez or the sumptuous manor house Pazo de Lourizán. 5 - Poio The region also gathers an important archaeological heritage, such as 6 - Barro the groups of rock carvings - petroglyphs - from the Bronze Age that can 7 - Campo Lameiro be admired in Campo Lameiro, Tourón or A Caeira. The coastal inlet Ría de Pontevedra, with towns such as Poio or the parishes of Combarro or Samieira, is home to an interesting culinary offer and boasts a large number of interesting natural and cultural spots.