St Michael's Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

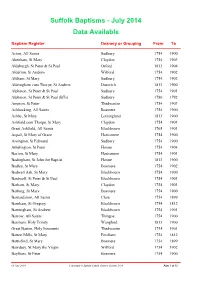

Baptism Data Available

Suffolk Baptisms - July 2014 Data Available Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping From To Acton, All Saints Sudbury 1754 1900 Akenham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1903 Aldeburgh, St Peter & St Paul Orford 1813 1904 Alderton, St Andrew Wilford 1754 1902 Aldham, St Mary Sudbury 1754 1902 Aldringham cum Thorpe, St Andrew Dunwich 1813 1900 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul Sudbury 1754 1901 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul (BTs) Sudbury 1780 1792 Ampton, St Peter Thedwastre 1754 1903 Ashbocking, All Saints Bosmere 1754 1900 Ashby, St Mary Lothingland 1813 1900 Ashfield cum Thorpe, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Great Ashfield, All Saints Blackbourn 1765 1901 Aspall, St Mary of Grace Hartismere 1754 1900 Assington, St Edmund Sudbury 1754 1900 Athelington, St Peter Hoxne 1754 1904 Bacton, St Mary Hartismere 1754 1901 Badingham, St John the Baptist Hoxne 1813 1900 Badley, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1902 Badwell Ash, St Mary Blackbourn 1754 1900 Bardwell, St Peter & St Paul Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Barking, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1900 Barnardiston, All Saints Clare 1754 1899 Barnham, St Gregory Blackbourn 1754 1812 Barningham, St Andrew Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barrow, All Saints Thingoe 1754 1900 Barsham, Holy Trinity Wangford 1813 1900 Great Barton, Holy Innocents Thedwastre 1754 1901 Barton Mills, St Mary Fordham 1754 1812 Battisford, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1899 Bawdsey, St Mary the Virgin Wilford 1754 1902 Baylham, St Peter Bosmere 1754 1900 09 July 2014 Copyright © Suffolk Family History Society 2014 Page 1 of 12 Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping -

Excursion, 24 July 1976: Denston Church, Hall, And

1976 24 July Denstonchurch,HallandChantryFarm: The church is evidently a rebuilding for servicesof new collegiatefoundation of 1475.Master and brethren apparently lived in former building W. of church. Present Chantry Farm E. of church, with notable Tudor woodwork,is a post- Reformationparsonagehouse. At the Hall, John Bensusan-Buttestablishedthe probability that the rear range was the remnant of the large, quadrangular house of SirJohn Denston,founder of the chantry; that the present main house was built c. 1690for Sir John Robinson (d. temp.Anne), the chief remains being the barley-twist staircase, the black-and-red brickworkand the small-paned windowsat rear; and that alterations, mainly in the front of the house, were perhaps paid for by SirJohn GriffinGriffinat the time of the Robinson-Clivemarriage, 1782. BadmondisfieldHall,Wickhambrook: Domesdaysite with own church evidently near front of present house and apparently dedicated to St Edward. Present building presumably Eliza- bethan. Garderobe survives in upper chamber. Two handsome medieval carved wooden doorwaysstand within, but whether in situis uncertain. XS. 11 September Mildenhallchurch:Dramatic nave, rebuilt x5th century and grafted on to earlier chancel. Remarkable slab in memoryof Richard de Wickforderefersto the 'new work' of the chancel (c. 1300).13th-centurynorth chapel with stone vault. Mildenhalltownandparish:W. of church, ruins of a large rectangular dovecotewith stone nesting-boxes;once belongingto the manor-house,probably medieval. The River Lark, which was probably -

Heritage Impact Assessment for Local Plan Site Allocations Stage 1: Strategic Appraisal

Babergh & Mid Suffolk District Councils Heritage Impact Assessment for Local Plan Site Allocationsx Stage 1: strategic appraisal Final report Prepared by LUC October 2020 Babergh & Mid Suffolk District Councils Heritage Impact Assessment for Local Plan Site Allocations Stage 1: strategic appraisal Project Number 11013 Version Status Prepared Checked Approved Date 1. Draft for review R. Brady R. Brady S. Orr 05.05.2020 M. Statton R. Howarth F. Smith Nicholls 2. Final for issue R. Brady S. Orr S. Orr 06.05.2020 3. Updated version with additional sites F. Smith Nicholls R. Brady S. Orr 12.05.2020 4. Updated version - format and typographical K. Kaczor R. Brady S. Orr 13.10.2020 corrections Bristol Land Use Consultants Ltd Landscape Design Edinburgh Registered in England Strategic Planning & Assessment Glasgow Registered number 2549296 Development Planning London Registered office: Urban Design & Masterplanning Manchester 250 Waterloo Road Environmental Impact Assessment London SE1 8RD Landscape Planning & Assessment landuse.co.uk Landscape Management 100% recycled paper Ecology Historic Environment GIS & Visualisation Contents HIA Strategic Appraisal October 2020 Contents Cockfield 18 Wherstead 43 Eye 60 Chapter 1 Copdock 19 Woolverstone 45 Finningham 62 Introduction 1 Copdock and Washbrook 19 HAR / Opportunities 46 Great Bicett 62 Background 1 East Bergholt 22 Great Blakenham 63 Exclusions and Limitations 2 Elmsett 23 Great Finborough 64 Chapter 4 Sources 2 Glemsford 25 Assessment Tables: Mid Haughley 64 Document Structure 2 Great Cornard -

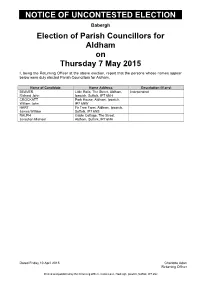

Notice of Uncontested Election

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Parish Councillors for Aldham on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Aldham. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BEAVER Little Rolls, The Street, Aldham, Independent Richard John Ipswich, Suffolk, IP7 6NH CROCKATT Park House, Aldham, Ipswich, William John IP7 6NW HART Fir Tree Farm, Aldham, Ipswich, James William Suffolk, IP7 6NS RALPH Gable Cottage, The Street, Jonathan Michael Aldham, Suffolk, IP7 6NH Dated Friday 10 April 2015 Charlotte Adan Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Corks Lane, Hadleigh, Ipswich, Suffolk, IP7 6SJ NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Parish Councillors for Alpheton on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Alpheton. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ARISS Green Apple, Old Bury Road, Alan George Alpheton, Sudbury, CO10 9BT BARRACLOUGH High croft, Old Bury Road, Richard Alpheton, Suffolk, CO10 9BT KEMP Tresco, New Road, Long Melford, Independent Richard Edward Suffolk, CO10 9JY LANKESTER Meadow View Cottage, Bridge Maureen Street, Alpheton, Suffolk, CO10 9BG MASKELL Tye Farm, Alpheton, Sudbury, Graham Ellis Suffolk, CO10 9BL RIX Clapstile Farm, Alpheton, Farmer Trevor William Sudbury, Suffolk, CO10 9BN WATKINS 3 The Glebe, Old Bury Road, Ken Alpheton, Sudbury, Suffolk, CO10 9BS Dated Friday 10 April 2015 Charlotte Adan Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Corks Lane, Hadleigh, Ipswich, Suffolk, IP7 6SJ NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Parish Councillors for Assington on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Assington. -

Alan Mackley, 'The Construction of Henham Hall', the Georgian Group

Alan Mackley, ‘The Construction of Henham Hall’, The Georgian Group Jounal, Vol. VI, 1996, pp. 85–96 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 1996 THE CONSTRUCTION OF HENHAM HALL Alan Mackley uring the night of Saturday 8 May 1773, Henham Hall in east Suffolk was destroyed by fire, the result, it was said, of the carelessness of a drunken butler whose candle fell whilst he robbed the wine cellar during his master’s absence in Italy.1 The uninsured loss was Dreported to be £30,000.2 This was a serious blow for the 23-year old sixth baronet, Sir John Rous, who had succeeded his father just two years before. The loss represented at least eight years’ rental income from his landed estate.3 Almost twenty years elapsed before rebuilding began. John Rous’s surviving letters and accounts throw a revealing light on the reasons for the delay. Additionally, the survival of detailed building accounts and his clerk of works’s reports permit the almost total reconstruction of the building process at Henham in the 1790s.4 The existence of plans dated 1774 by James Byres indicate an early interest in rebuilding, but Rous’s letters in the 1780s, before he married, reveal an equivocal attitude to investment in his estate, concern about his financial position, and pessimism about the future.5 His views were not untypical of that generation of landowners who lived through the dramatic collapse of land and farm prices at the end of the war of American Independence. Rous had little income beyond the £3,600 generated annually by his Suffolk estate. -

Notice of Poll Babergh

Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF COUNTY COUNCILLOR FOR THE BELSTEAD BROOK DIVISION NOTICE OF POLL NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT :- 1. A Poll for the Election of a COUNTY COUNCILLOR for the above named County Division will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 7:00am and 10:00pm. 2. The number of COUNTY COUNCILLORS to be elected for the County Division is 1. 3. The names, in alphabetical order and other particulars of the candidates remaining validly nominated and the names of the persons signing the nomination papers are as follows:- SURNAME OTHER NAMES IN HOME ADDRESS DESCRIPTION PERSONS WHO SIGNED THE FULL NOMINATION PAPERS 16 Two Acres Capel St. Mary Frances Blanchette, Lee BUSBY DAVID MICHAEL Liberal Democrats Ipswich IP9 2XP Gifkins CHRISTOPHER Address in the East Suffolk The Conservative Zachary John Norman, Nathan HUDSON GERARD District Party Candidate Callum Wilson 1-2 Bourne Cottages Bourne Hill WADE KEITH RAYMOND Labour Party Tom Loader, Fiona Loader Wherstead Ipswich IP2 8NH 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the descriptions of the persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows:- POLLING POLLING STATION DESCRIPTIONS OF PERSONS DISTRICT ENTITLED TO VOTE THEREAT BBEL Belstead Village Hall Grove Hill Belstead IP8 3LU 1.000-184.000 BBST Burstall Village Hall The Street Burstall IP8 3DY 1.000-187.000 BCHA Hintlesham Community Hall Timperleys Hintlesham IP8 3PS 1.000-152.000 BCOP Copdock & Washbrook Village Hall London Road Copdock & Washbrook Ipswich IP8 3JN 1.000-915.500 BHIN Hintlesham Community Hall Timperleys Hintlesham IP8 3PS 1.000-531.000 BPNN Holiday Inn Ipswich London Road Ipswich IP2 0UA 1.000-2351.000 BPNS Pinewood - Belstead Brook Muthu Hotel Belstead Road Ipswich IP2 9HB 1.000-923.000 BSPR Sproughton - Tithe Barn Lower Street Sproughton IP8 3AA 1.000-1160.000 BWHE Wherstead Village Hall Off The Street Wherstead IP9 2AH 1.000-244.000 5. -

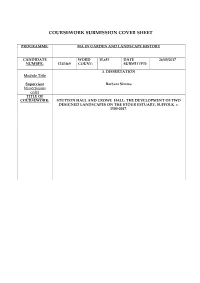

Coursework Submission Cover Sheet

COURSEWORK SUBMISSION COVER SHEET PROGRAMME: MA IN GARDEN AND LANDSCAPE HISTORY CANDIDATE WORD 15,653 DATE 26/09/2017 NUMBER: 1545469 COUNT: SUBMITTED: 3. DISSERTATION Module Title Supervisor Barbara Simms (dissertations only) TITLE OF COURSEWORK: STUTTON HALL AND CROWE HALL: THE DEVELOPMENT OF TWO DESIGNED LANDSCAPES ON THE STOUR ESTUARY, SUFFOLK. c. 1500-2017. STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP FORM Name: Patience Shone Course title: MA in Landscape and Garden History Essay title: Assignment 3.Dissertation. Stutton Hall and Crowe Hall: The Development of Two Designed Landscapes on the Stour Estuary, Suffolk.c.1500 to 2017 Name of tutor: Barbara Simms Due date: 27/09/2017 I declare that the attached essay/dissertation is my own work and that all sources quoted, paraphrased or otherwise referred to are acknowledged in the text, as well as in the list of ‘Works Cited’. Signature: Date submitted: 26/09/2017 Received by: (signature) Date submitted: 1 STUTTON HALL AND CROWE HALL: THE DEVELOPMENT OF TWO DESIGNED LANDSCAPES ON THE STOUR ESTUARY, SUFFOLK. c.1500-2017. Figure 1. The Stour Estuary from Stutton, by Gay Strutt, Stutton Hall. THE INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH MA IN GARDEN AND LANDSCAPE HISTORY MODULE 3, DISSERTATION STUDENT NUMBER : 1545469 Submitted 27/09/2017 2 CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 LIST OF FIGURES 6 (1,160 words) INTRODUCTION 11 CHAPTER ONE 16 LOCATION GEOLOGY 19 CLIMATE 21 CHAPTER TWO HISTORY OF SETTLEMENT 22 CHAPTER THREE ASPECT AND TOPOGRAPHY, THE SETTING 27 CHAPTER FOUR: STUTTON HALL 29 OWNERSHIP -

2A 2 93 92 9497 98

Babergh and Essex Services 2 2A 92 93 94 97 98 695 Your guide to our bus services from Ipswich into Babergh, Essex & Tendering Bus times from Sunday 29th August 2021 2/2A Clacton | Clacton Shopping Village | Weeley | Tendring | Manningtree | Mistley Mondays to Saturdays Service Number 2A ◆ 2◆ 2◆ 2◆ 2A ◆ 2◆ Clacton, Pier Avenue 0625 0830 1055 1300 1525 1735 Clacton, Rail Station 0627 0832 1057 1302 1527 1737 Clacton, Valley Road, The Range 0632 0837 1102 1307 1532 1742 Clacton, Shopping Village 0639 0844 1109 1314 1539 1749 Clacton, Lt Clacton Morrisons 0641 0846 1111 1316 1541 1751 Little Clacton, Blacksmiths Arms 0645 0850 1115 1320 1545 1755 2 Weeley, The Street 0651 0856 1121 1326 1551 1801 Tendring Heath, Hall Lane 0658 0903 1128 1333 1558 1808 Little Bentley, Bricklayers Arms — 0908 1133 1338 — 1813 Little Bromley, Post Office — 0918 1143 1348 — 1823 Lawford, Place — 0921 1146 1351 — 1826 Manningtree Rail Station — 0925 1150 1355 — 1830 Manningtree, High School — 0930 1155 1400 — 1835 Mistley Church — 0933 1158 1403 — 1838 Horsley Cross, Cross Inn 0702 — — — 1602 — Mistley Heath 0710 — — — 1610 — Mistley, Rigby Avenue 0713 0935 1200 1405 1613 1840 Code: ◆ - This journey is sponsored by Essex County Council No service on Sundays or Bank Holidays 2/2A Mistley | Manningtree | Tendring | Weeley | Clacton Shopping Village | Clacton Mondays to Saturdays Service Number 2◆ 2◆ 2A ◆ 2◆ 2◆ 2◆ Mistley, Rigby Avenue 0715 0940 1202 1410 1615 1845 Mistley Heath — — 1205 — — — Horsley Cross, Cross Inn — — 1213 — — — Mistley, Church 0718 0943 — 1413 -

Election of County Councillor

Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF COUNTY COUNCILLOR FOR THE BELSTEAD BROOK DIVISION NOTICE OF POLL NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT :- 1. A Poll for the Election of a COUNTY COUNCILLOR for the above named County Division will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 7:00am and 10:00pm. 2. The number of COUNTY COUNCILLORS to be elected for the County Division is 1. 3. The names, in alphabetical order and other particulars of the candidates remaining validly nominated and the names of the persons signing the nomination papers are as follows:- SURNAME OTHER NAMES IN HOME ADDRESS DESCRIPTION PERSONS WHO SIGNED THE FULL NOMINATION PAPERS 16 Two Acres Capel St. Mary Frances Blanchette, Lee BUSBY DAVID MICHAEL Liberal Democrats Ipswich IP9 2XP Gifkins CHRISTOPHER Address in the East Suffolk The Conservative Zachary John Norman, Nathan HUDSON GERARD District Party Candidate Callum Wilson 1-2 Bourne Cottages Bourne Hill WADE KEITH RAYMOND Labour Party Tom Loader, Fiona Loader Wherstead Ipswich IP2 8NH 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the descriptions of the persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows:- POLLING POLLING STATION DESCRIPTIONS OF PERSONS DISTRICT ENTITLED TO VOTE THEREAT BBEL Belstead Village Hall Grove Hill Belstead IP8 3LU 1.000-184.000 BBST Burstall Village Hall The Street Burstall IP8 3DY 1.000-187.000 BCHA Hintlesham Community Hall Timperleys Hintlesham IP8 3PS 1.000-152.000 BCOP Copdock & Washbrook Village Hall London Road Copdock & Washbrook Ipswich IP8 3JN 1.000-915.500 BHIN Hintlesham Community Hall Timperleys Hintlesham IP8 3PS 1.000-531.000 BPNN Holiday Inn Ipswich London Road Ipswich IP2 0UA 1.000-2351.000 BPNS Pinewood - Belstead Brook Muthu Hotel Belstead Road Ipswich IP2 9HB 1.000-923.000 BSPR Sproughton - Tithe Barn Lower Street Sproughton IP8 3AA 1.000-1160.000 BWHE Wherstead Village Hall Off The Street Wherstead IP9 2AH 1.000-244.000 5. -

Babergh District Council Work Completed Since April

WORK COMPLETED SINCE APRIL 2015 BABERGH DISTRICT COUNCIL Exchange Area Locality Served Total Postcodes Fibre Origin Suffolk Electoral SCC Councillor MP Premises Served Division Bildeston Chelsworth Rd Area, Bildeston 336 IP7 7 Ipswich Cosford Jenny Antill James Cartlidge Boxford Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 185 CO10 5 Sudbury Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Bures Church Area, Bures 349 CO8 5 Sudbury Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Clare Stoke Road Area 202 CO10 8 Haverhill Clare Mary Evans James Cartlidge Glemsford Cavendish 300 CO10 8 Sudbury Clare Mary Evans James Cartlidge Hadleigh Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 255 IP7 5 Ipswich Hadleigh Brian Riley James Cartlidge Hadleigh Brett Mill Area, Hadleigh 195 IP7 5 Ipswich Samford Gordon Jones James Cartlidge Hartest Lawshall 291 IP29 4 Bury St Edmunds Melford Richard Kemp James Cartlidge Hartest Hartest 148 IP29 4 Bury St Edmunds Melford Richard Kemp James Cartlidge Hintlesham Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 136 IP8 3 Ipswich Belstead Brook David Busby James Cartlidge Nayland High Road Area, Nayland 228 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Maple Way Area, Nayland 151 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Church St Area, Nayland Road 408 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Bear St Area, Nayland 201 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 271 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Shotley Shotley Gate 201 IP9 1 Ipswich -

April 2010 Bboxfoord • Xedwardsrtone • Igrovton •Elitrtle Walndingfieled • Nwewton Sgreen Vol 10 No 4 BBC SHOWCASE for BOXFORD BAND FINLAY HUNTERS ACHIEVEMENT AWARD

April 2010 BBoxfoord • xEdwardsRtone • iGrovton •eLitrtle WalNdingfieled • Nwewton sGreen Vol 10 No 4 BBC SHOWCASE FOR BOXFORD BAND FINLAY HUNTERS ACHIEVEMENT AWARD Left to right: Mark Willis, Chris Athorne, Robert Lait and Lee Wilkins Boxford band This Boy Wonders featured on the BBC Introducing series on Radio Suffolk last month, playing two songs live. The show, broadcast from The Fleece, was hosted by presenters Graeme Mac and Richard Haugh. The four piece band featuring Chris Athorne (Vocals & Lead Guitar), Lee Wilkins (Rhythm Guitar), Robert Lait (Bass) and Mark Willis Above: Finlay receiving his award from Robert Audley, Chairman of Prolog (Drums) also played a 45 minute set on the night which was recorded by (sponsors) and Jennie Jenkins, Chair of Babergh District Council. BBC engineers for broadcast on the show later this year. All band Finlays citation read:- members are resident in the village. FINLAY has worked tirelessly to restore the Village Hall for the benefit This Boy Wonders were joined on the night by Haverhill outfit, of the village. Over the years the Hall had deteriorated and Finlay was Umbrella Assassins, whose sound harked back to the thrash punk of the instrumental in getting it re-decorated in order to secure further 1980’s. bookings. His greatest achievement was over the past year where, The BBC show marked a high point for the Boxford band, who were supported by his committee, he led a costly project to construct a new formed at the end of 2008. The two songs broadcast, ‘All I Know’ and roof on the hall which involved renewing all the electrics. -

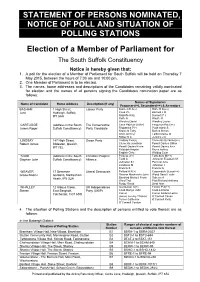

Statement of Persons Nominated & Notice of Poll & Situation of Polling

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED, NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS Election of a Member of Parliament for The South Suffolk Constituency Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a Member of Parliament for South Suffolk will be held on Thursday 7 May 2015, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. One Member of Parliament is to be elected. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors BASHAM 1 High Street, Labour Party Dunnett E A(+) Rolfe R D(++) Jane Hadleigh, Suffolk, Cook P F Barford J M IP7 5AH Ratcliffe Katy Dunnett P J Rolfe A Woulfe K Wordley David Wordley Louise CARTLIDGE (address in the South The Conservative Cave Patricia G M(+) Ferguson Paul(++) James Roger Suffolk Constituency) Party Candidate Fitzpatrick P H Pugh Alaric S Kramers Toby Barrett Simon Antill Jennifer Talbot Clarke D Ridley N A Jenkins J A LINDSAY 147 High Street, Green Party Lindsay Eva(+) Clements Suzanne(++) Robert James Bildeston, Ipswich, Clements Jonathan Powell Davies Gillian IP7 7EL Powell Davies Kevin Powell Davies Alex Biddulph Angela Bruce Ashley English Chloe Widdup Colin TODD (address in the South Christian Peoples Pickess J(+) Tuttlebury M(++) Stephen John Suffolk Constituency) Alliance Todd A Johnston Elizabeth M Johnston S L Percival Julie Landman M Johnston