CAVES and KARST Research in Speleology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats, and Tunnels in Afghanistan: an Annotated Bibliography by R

Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats, and Tunnels in Afghanistan: An Annotated Bibliography by R. Lee Hadden Topographic Engineering Center November 2005 US Army Corps of Engineers 7701 Telegraph Road Alexandria, VA 22315-3864 Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats, and Tunnels In Afghanistan Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE 30-11- 2. REPORT TYPE Bibliography 3. DATES COVERED 1830-2005 2005 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER “Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats and Tunnels 5b. GRANT NUMBER In Afghanistan: An Annotated Bibliography” 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER HADDEN, Robert Lee 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT US Army Corps of Engineers 7701 Telegraph Road Topographic Alexandria, VA 22315- Engineering Center 3864 9.ATTN SPONSORING CEERD / MONITORINGTO I AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

Airborne Microorganisms in Lascaux Cave (France) Pedro M

International Journal of Speleology 43 (3) 295-303 Tampa, FL (USA) September 2014 Available online at scholarcommons.usf.edu/ijs/ & www.ijs.speleo.it International Journal of Speleology Off icial Journal of Union Internationale de Spéléologie Airborne microorganisms in Lascaux Cave (France) Pedro M. Martin-Sanchez1, Valme Jurado1, Estefania Porca1, Fabiola Bastian2, Delphine Lacanette3, Claude Alabouvette2, and Cesareo Saiz-Jimenez1* 1Instituto de Recursos Naturales y Agrobiología de Sevilla, IRNAS-CSIC, Apartado 1052, 41080 Sevilla, Spain 2UMR INRA-Université de Bourgogne, Microbiologie du Sol et de l’Environnement, BP 86510, 21065 Dijon Cedex, France 3Université de Bordeaux, I2M, UMR 5295, 16 Avenue Pey-Berland, 33600 Pessac, France Abstract: Lascaux Cave in France contains valuable Palaeolithic paintings. The importance of the paintings, one of the finest examples of European rock art paintings, was recognized shortly after their discovery in 1940. In the 60’s of the past century the cave received a huge number of visitors and suffered a microbial crisis due to the impact of massive tourism and the previous adaptation works carried out to facilitate visits. In 1963, the cave was closed due to the damage produced by visitors’ breath, lighting and algal growth on the paintings. In 2001, an outbreak of the fungus Fusarium solani covered the walls and sediments. Later, black stains, produced by the growth of the fungus Ochroconis lascauxensis, appeared on the walls. In 2006, the extensive black stains constituted the third major microbial crisis. In an attempt to know the dispersion of microorganisms inside the cave, aerobiological and microclimate studies were carried out in two different seasons, when a climate system for preventing condensation of water vapor on the walls was active (September 2010) or inactive (February 2010). -

Underwater Speleology Journal of the Cave Diving Section of the National Speleological Society CONTENTS

Underwater Speleology Journal of the Cave Diving Section of the National Speleological Society CONTENTS Jackson Blue Springs. Photographer: Mat Bull...........................................Cover From the Chairman.....................................................................................3 Little Hole, Big Finds: Diving Tulum’s Chan Hol..........................................4 Agnes Milowka Memorial...........................................................................11 Skills, tips & Techniques............................................................................12 Wes Skiles Peacock Springs Interpretive Trail..........................................14 Cave diving Milestones.............................................................................17 Visit With A Cave: Madison Blue Springs..................................................18 Conservation Corner.................................................................................21 Australia: Down Under Diary.....................................................................22 Workshop 2011.........................................................................................29 News Reel.................................................................................................30 from the Chairman gene melton “The root of joy, as of duty, is to put all of one’s powers towards some great end.” - Oliver Wendell Holmes. Throughout all of our experiences, we sometimes find ourselves standing on a knife edge. We can fall off one side due to over -

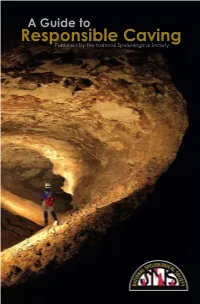

A Guide to Responsible Caving Published by the National Speleological Society a Guide to Responsible Caving

A Guide to Responsible Caving Published by The National Speleological Society A Guide to Responsible Caving National Speleological Society 2813 Cave Avenue Huntsville, AL 35810 256-852-1300 [email protected] www.caves.org Fourth Edition, 2009 Text: Cheryl Jones Design: Mike Dale/Switchback Design Printing: Raines This publication was made possible through a generous donation by Inner Mountain Outfitters. Copies of this Guide may be obtained through the National Speleological Society Web site. www.caves.org © Copyright 2009, National Speleological Society FOREWORD We explore caves for many reasons, but mainly for sport or scientific study. The sport caver has been known as a spelunker, but most cave explorers prefer to be called cavers. Speleology is the scientific study of the cave environment. One who studies caves and their environments is referred to as a speleologist. This publication deals primarily with caves and the sport of caving. Cave exploring is becoming increasingly popular in all areas of the world. The increase in visits into the underground world is having a detrimental effect on caves and relations with cave owners. There are many proper and safe caving methods. Included here is only an introduction to caves and caving, but one that will help you become a safe and responsible caver. Our common interests in caving, cave preservation and cave conservation are the primary reasons for the National Speleological Society. Whether you are a beginner or an experienced caver, we hope the guidelines in this booklet will be a useful tool for remembering the basics which are so essential to help preserve the cave environment, to strengthen cave owner relations with the caving community, and to make your visit to caves a safe and enjoyable one. -

Caves in New Mexico and the Southwest Issue 34

Lite fall 2013 Caves in New Mexico and the Southwest issue 34 The Doll’s Theater—Big Room route, Carlsbad Cavern. Photo by Peter Jones, courtesy of Carlsbad Caverns National Park. In This Issue... Caves in New Mexico and the Southwest Cave Dwellers • Mapping Caves Earth Briefs: Suddenly Sinkholes • Crossword Puzzle New Mexico’s Most Wanted Minerals—Hydromagnesite New Mexico’s Enchanting Geology Classroom Activity: Sinkhole in a Cup Through the Hand Lens • Short Items of Interest NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF GEOLOGY & MINERAL RESOURCES A DIVISION OF NEW MEXICO TECH http://geoinfo.nmt.edu/publications/periodicals/litegeology/current.html CAVES IN NEW MEXICO AND THE SOUTHWEST Lewis Land Cave Development flowing downward from the surface. Epigenic A cave is a naturally-formed underground cavity, usually caves can be very long. with a connection to the surface that humans can enter. The longest cave in the Caves, like sinkholes, are karst features. Karst is a type of world is the Mammoth landform that results when circulating groundwater causes Cave system in western voids to form due to dissolution of soluble bedrock. Karst Kentucky, with a surveyed terrain is characterized by sinkholes, caves, disappearing length of more than 400 streams, large springs, and underground drainage. miles (643 km). The largest and most common caves form by dissolution of In recent years, limestone or dolomite, and are referred to as solution caves. scientists have begun to Limestone and dolomite rock are composed of the minerals recognize that many caves calcite (CaCO ) and dolomite (CaMg(CO ) ), which are 3 3 2 are hypogenic in origin, soluble in weak acids such as carbonic acid (H CO ), and are 2 3 meaning that they were thus vulnerable to dissolution by groundwater. -

Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Dark

World Heritage 43 COM Patrimoine mondial Paris, 23 November 2018 Original: English / français UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L'EDUCATION, LA SCIENCE ET LA CULTURE CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE CONVENTION CONCERNANT LA PROTECTION DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL, CULTUREL ET NATUREL WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE / COMITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL Forty-third session / Quarante-troisième session Baku, Azerbaijan / Bakou, Azerbaidjan 30 June - 10 July 2019 / 30 juin - 10 juillet 2019 Item 7 of the Provisional Agenda: State of conservation of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List and/or on the List of World Heritage in Danger Point 7 de l’Ordre du jour provisoire: Etat de conservation de biens inscrits sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial et/ou sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial en péril MISSION REPORT / RAPPORT DE MISSION Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park (Viet Nam) (951bis) Parc national de Phong Nha-Ke Bang (Viet Nam) (951 bis) 11-20 July 2018 Report on the Joint WHC/IUCN Reactive Monitoring Mission to Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park (11-20 July 2018) REPORT ON THE JOINT WORLD HERITAGE CENTRE/IUCN REACTIVE MONITORING MISSION TO PHONG NHA-KE BANG NATIONAL PARK (VIET NAM) FROM 11 TO 20 JULY 2018 Photo © IUCN / Remco van Merm July 2018 2 Report on the Joint WHC/IUCN Reactive Monitoring Mission to Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park (11-20 July 2018) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................................5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY, OVERALL APPRAISAL AND LIST OF RECOMMENDATIONS ................6 1 BACKGROUND TO THE MISSION ............................................................................................ 14 1.1 Inscription History ........................................................................................................... -

Guide to Responsible Caving

Published by the National Speleological Society Photo by Ryan Maurer 1 A Guide to Responsible Caving National Speleological Society 6001 Pulaski Pike Huntsville, AL 35810-1122 256-852-1300 • [email protected] www.caves.org Fifth Edition, 2016 Text: Cheryl Jones Design: Mike Dale/Switchback Design Photos: Selected from those accepted for show in the 2015 NSS Photo Salon Printing: Terry Raines Copies of this Guide may be obtained through the National Speleological Society website. www.caves.org © Copyright 2016, National Speleological Society FOREWORD aving can be a rewarding, safe, and fun activity when you are properly trained, equipped, and Cprepared. But there is more to being a “real” caver than having the correct skills and gear: you also must be a responsible caver. This means you show respect for the cave, and its challenges, environment, and creatures, as well as for cave owners and their property. This is critical to preserving the cave wilderness and keeping caves open to cavers for years to come. In this booklet, the National Speleological Society (NSS) provides an introduction to becoming a responsible caver. We hope these guidelines will help make your ventures underground safe and enjoyable, and pave the way for you to become a respected member of the caving community. I encourage you to join a local chapter of the NSS to develop your skills and knowledge with experienced cavers and speleologists, and become a part of the caving community. This is the fifth edition of my original booklet, A Guide to Responsible Caving. A special thank-you to my fellow cavers for their hard work and dedication: Cheryl Jones for revising and editing this publication and Michael Dale for the design and layout. -

The Prehistoric Cave Art and Archaeology of Dunbar Cave, Montgomery County, Tennessee

J.F. Simek, S.A. Blankenship, A. Cressler, J.C. Douglas, A. Wallace, D. Weinand, and H. Welborn – The prehistoric cave art and archaeology of Dunbar Cave, Montgomery County, Tennessee. Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, v. 74, no. 1, p. 19–32. DOI: 10.4311/ 2011AN0219 THE PREHISTORIC CAVE ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY OF DUNBAR CAVE, MONTGOMERY COUNTY, TENNESSEE JAN F. SIMEK1*,SARAH A. BLANKENSHIP1,ALAN CRESSLER2,JOSEPH C. DOUGLAS3,AMY WALLACE4, DANIEL WEINAND1, AND HEATHER WELBORN1 Abstract: Dunbar Cave in Montgomery County, Tennessee has been used by people in a great variety of ways. This paper reports on prehistoric uses of the cave, which were quite varied. The vestibule of the cave, which is today protected by a concrete slab installed during the cave’s days as an historic tourist showplace, saw extensive and very long term occupation. Diagnostic artifacts span the period from Late Paleo-Indian (ca.10,000-years ago) to the Mississippian, and include Archaic (10,000 to 3,000-years ago) and Woodland (3,000–1,000-years ago) cultural materials. These include a paleoindian Beaver Lake Point, Kirk cluster points, Little River types, Ledbetter types, numerous straight-stemmed point types, Hamilton and Madison projectile points. Woodland period ceramics comprise various limestone tempered forms, all in low quantities, and cord-marked limestone tempered wares in the uppermost Woodland layers. Shell-tempered ceramics bear witness to a rich Mississippian presence at the top of the deposit. Given this chronological span, the Dunbar Cave sequence is as complete as any in eastern North America. However, problems with previous excavation strategies make much of the existing archaeological record difficult to interpret. -

Occurrence and Absence of Lava Tube Caves with Some Other Volcanic Cavities; a Consideration of Hu- Man Habitation Sites on Mars

43rd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2012) 1613.pdf Occurrence and Absence Of Lava Tube Caves With Some Other Volcanic Cavities; a Consideration of Hu- man Habitation Sites on Mars. W.R. Halliday (1,2), G. Favre (1,3), A. Stefansson (4), P. Whitfield (5) and N. Banks (6). 1) Commission on Volcanic Caves of the International Union of Speleology, 2) Hawaii Speleological Survey of the National Speleological Society, 3) Swiss Speleological Society, 4) Thrihnukar e.h.f., 5) British Colum- bia Speleological Federation and 6) US Geological Survey (retired). [email protected], 6530 Cornwall Court, Nashville, TN 37205 USA In 1839, American missionaries in the Kingdom of ern pit crater was seen to be much like the western ex- Hawaii showed professor-to-be James Dana some lo- ample, plus a small alcove at its base. Its walls contain cally celebrated pit craters on the east rift zone of Ki- three rudimentary lava tubes much like those in the lauea Volcano (1). Dana recognized them as rem- western pit crater, but it does not connect to any lava nants of circular pools of molten lava with subsequent tube feeding system, and as Favre remarked (5), it does withdrawal of their lava column. Other pit craters were not “open out into a vast underground system”. De- found around the world, perhaps most notably on the spite published statements to the contrary, no terrestrial rift zones of Hawaii’s Hualalai Volcano where they are pit crater has been documented as a skylight of any so isolated that few have been investigated. -

Spelunking: Safety Activity Checkpoints

Spelunking: Safety Activity Checkpoints Spelunking” (speh-LUNK-ing) or caving, is an exciting, hands-on way to learn about speleology (spee-lee-AH-luh-gee), the study of caves, as well as paleontology (pay-lee- en-TAH-luh-gee), the study of life from past geologic periods by examining plant and animal fossils. As a sport, caving is similar to rock climbing, and often involves using ropes to crawl and climb through cavern nooks and crannies. These checkpoints do not apply to groups taking trips to tourist or commercial caves, which often include safety features such as paths, electric lights, and stairways. Caving is not permitted for Girl Scout Daisies and Brownies. Never go into a cave alone. Never go caving with fewer than 4 in your group. Appoint a reliable, experienced caver, as the “trail guide” or “sweeper” whose job it is to keep the group together. When climbing in a cave, always use three points of contact, hands, feet knees and possibly, the seat of your pants (the cave scoot). Know where to go spelunking. Connect with your Girl Scout council for site suggestions. Also, the National Speleological Society provides an online search tool for U.S. caving clubs, and the National Park Service provides information about National Park caves. www.nps.gov Include girls with disabilities. Communicate with girls with disabilities and/or their caregivers to assess any needs and accommodations. Learn more about the resources and information that the National Center on Health, Physical Activities and Disabilities provides to people with disabilities. -

Three-Dimensional Mapping of an Ancient Cave Paintings Using Close-Range Photogrammetry and Terrestrial Laser Scanning Technologies

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLII-2/W3, 2017 3D Virtual Reconstruction and Visualization of Complex Architectures, 1–3 March 2017, Nafplio, Greece THREE-DIMENSIONAL MAPPING OF AN ANCIENT CAVE PAINTINGS USING CLOSE-RANGE PHOTOGRAMMETRY AND TERRESTRIAL LASER SCANNING TECHNOLOGIES a a a a a a b b Z. Majid , M. F. M. Ariff , K. M. Idris , A. R. Yusoff , K.M. Idris , A. Aspuri , M.A.Abbas , K. Zainuddin , A. R. A. c c, Ghani , Ardi * a Geospatial Imaging and Information Research Group, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, MALAYSIA – zulkeplimajid, mfaridma, [email protected] b Universiti Teknologi MARA, Arau, Perlis, MALAYSIA – [email protected], [email protected] c Department Of National Heritage, MALAYSIA – ardi, [email protected] Commission II KEYWORDS: three-dimensional, cave painting, terrestrial laser scanning, close-range photogrammetry, non-contact ABSTRACT: The paper describes the used of close-range photogrammetry and terrestrial laser scanning technologies as an innovative technology for acquiring the three-dimensional data of an ancient cave paintings. The close-range photogrammetry technology used in the research was divided in two categories which are the UAV-based close-range photogrammetry and the terrestrial- based close-range photogrammetry. The UAV-based technology involved with the used of calibrated Phantom 4 System while the terrestrial-based technology involved with the calibrated Sony F828 digital camera and pPhotoModeler software. Both stereo and convergent image acquisition techniques were used to acquire the images of the paintings. The ancient cave paintings were also recorded using terrestrial laser scanning technology. In the research, the FARO Focus 3D terrestrial laser scanner was used to capture the three-dimensional point clouds and images of the paintings. -

Anthropogenic Infilling of a Bermudian Sinkhole and Its Impact on Sedimentation and Benthic Foraminifera in the Adjacent Anchialine Cave Environment Jacquelyn N

International Journal of Speleology 46 (3) 409-425 Tampa, FL (USA) September 2017 Available online at scholarcommons.usf.edu/ijs International Journal of Speleology Off icial Journal of Union Internationale de Spéléologie Anthropogenic infilling of a Bermudian sinkhole and its impact on sedimentation and benthic foraminifera in the adjacent anchialine cave environment Jacquelyn N. Cresswell1, Peter J. van Hengstum2,3*, Thomas M. Iliffe1, Bruce E. Williams4, and Gil Nolan5 1Department of Marine Biology, Texas A&M University at Galveston, Galveston, Texas, 77554, USA 2Department of Marine Sciences, Texas A&M University at Galveston, Galveston, Texas, 77554, USA 3Department of Oceanography, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, 77843, USA 4Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences, Ferry Reach, St George’s Parish, GE 01, Bermuda 5Bermuda Zoological Society, Flatts, Hamilton Parish, FL BX, Bermuda Abstract: In the mid-20th century, an inland brackish pond from Bermuda, known as Eve’s Pond, was filled with marine sediment from an adjacent coastal lagoon. At this time, an eyewitness reported “…sediment billowing out of the Green Bay Cave for days…”, which is a marine- dominated anchialine cave located proximal to the former location of Eve’s Pond (~200 m). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the potential impact of this infilling event on cave sedimentation and benthic meiofaunal communities, as proxied by the unicellular protists foraminifera that remain preserved in the sediment record. Eight sediment cores were collected from an underwater passage in Green Bay Cave in a transect towards the location where Eve’s Pond was surveyed in 1901 CE. The sediment cores were analyzed for visual and density changes (photography, X-radiography), textural variability, benthic foraminifera fauna and diversity, and radiocarbon dating.