Analysis of RMA Plans and Issues Arising from the Tenure Review Process for Crown Pastoral Leases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

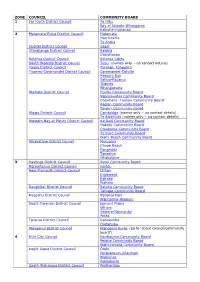

Zone Council Community Board 1 Far North District Council Te Hiku Bay

Zone Council Community Board 1 Far North District Council Te Hiku Bay of Islands-Whangaroa Kaikohe-Hokianga 2 Opotiki District Council Coast Otorohanga District Council Kawhia Otorohanga Rotorua District Council Rotorua Lakes South Waikato District Council Tirau Taupo District Council Turangi-Tongariro Thames-Coromandel District Council Coromandel-Colville Mercury Bay Tairua-Pauanui Thames Whangamate Waikato District Council Huntly Community Board Ngaruawahia Community Board Onewhero-Tuakau Community Board Raglan Communtiy Board Taupiri Community Board Waipa District Council Cambridge Te Awamutu Western Bay of Plenty District Council Katikati Community Board Maketu Community Board Omokoroa Community Board Te Puke Community Board Waihi Beach Community Board Whakatane District Council Murupara Ohope Beach Rangitaiki Taneatua Whakatane 3 Hastings District Council Rural Community Board Horowhenua District Council Foxton New Plymouth District Council Clifton Inglewood Kaitake Waitara Rangitiki District Council Ratana Community Board Taihape Community Board Ruapehu District Council National Park Waimarino-Waiouru South Taranaki District Council Egmont Plains Eltham Hawera-Normanby Patea Tararua District Council Dannevirke Eketahuna Wanganui District Council Wanganui Rural 4 Hutt City Council Eastbourne Community Board Petone Community Board Wainuiomata Community Board Kapiti Coast District Council Otaki Paraparaumu/Raumati Waikanae Paekakariki South Wairarapa District Council Featherston Greytown Martinborough Wellington City Council Makara-Ohariu -

Meeting Minutes

Meeting Minutes Meeting Name IPWEA Northern South Island Branch Meeting Meeting Venue CBay, Timaru Meeting Date 19 August, 10.00am Chair John Mackie Recorder Marieke van Genugten Attendees: 25 as listed Apologies: 5 as listed Welcome New Branch Chairman John Mackie opened the meeting and welcomed everyone at CBay in Timaru. Ashely Harper, Group Manager District Services at Timaru District Council, introduced himself and the Timaru District Council. Ashley took the opportunity to acknowledge that Timaru had won two IPWEA NZ Excellence Awards this year: Excellence in Strategic Planning – Winner o Timaru District-wide Wastewater Strategy - Timaru District Council, CH2M Beca Excellence in Maximising Asset Performance – Winner o Badhams Bridge Widening - Timaru District Council, Opus International Consultants, Whitestone Contracting IPWEA NZ Board Update John presented the new Board and invited everyone to consider upcoming IPWEA events, forums and training opportunities with a view to incorporating these into staff or self-development initiatives. After outlining the meeting agenda the chairman acknowledged and thanked the sponsors for the accommodation and for catering. Presentations 1. Waste Minimisation, 10 years on, by Ruth Clarke Ruth Clarke, Waste Minimisation Manager at Timaru District Council, outlined the work she and the Council have been undertaking for waste minimisation in Timaru and district. Ruth took us through the steps they’ve taken over the last 10 years to achieve today’s results. Recent customer research indicates a high level of satisfaction with waste minimisation services, specifically kerbside collections and transfer stations. The presentation was followed by Q&A and acknowledged with acclamation. 2. Waitaki river Bridges and Badhams Bridge Widening by Teresa Allen Teresa Allen’s, Senior Engineer, first presentation focused on the replacement of two single lane, 133 year old timber bridges over the Waitaki river. -

The Journey of Saving Not Just Land – but a Whole Island

The journey of saving not just land – but a whole island What was once an environmental hazard and wasteland is now a restored conservation area thanks to the determination and vision of a community group. Kurow Island is a ten-hectare island which sits within the mighty Waitaki River braided system. The island is Crown land and falls equally between the Waitaki and Waimate District Councils. Access to the island is by the way of State Highway 82 where the original historic twin bridges linked South Canterbury and North Otago. From the early 1900s to 1996 the central area of the island was used as a Waitaki District landfill. Following the closure of the landfill in 1996 the area became an illegal dumping site, a fire hazard and a wasteland covered in weeds. It was infested with pests, gorse and broom which was up to two metres high. Amongst the mess were dumped cars and animal carcasses and this was all visible from the road and bridges. In 2001 Meridian Energy announced their plans for Project Aqua which set to divert three quarters of the water from the Waitaki River to generate hydroelectricity, with the intention to create a recreational reserve with a lake on Kurow Island. In 2004 Project Aqua was abandoned and consequently so was the land proposal. This meant the island was left in its messy state. A group of Kurow locals came together to explore the idea of cleaning it up, to create a recreational and ecological area that benefited people, wildlife, and the environment. Sandy Cameron was a leader in this initiative and said what started out as an idea formed into a significant project. -

New Zealand National Climate Summary 2011: a Year of Extremes

NIWA MEDIA RELEASE: 12 JANUARY 2012 New Zealand national climate summary 2011: A year of extremes The year 2011 will be remembered as one of extremes. Sub-tropical lows during January produced record-breaking rainfalls. The country melted under exceptional heat for the first half of February. Winter arrived extremely late – May was the warmest on record, and June was the 3 rd -warmest experienced. In contrast, two significant snowfall events in late July and mid-August affected large areas of the country. A polar blast during 24-26 July delivered a bitterly cold air mass over the country. Snowfall was heavy and to low levels over Canterbury, the Kaikoura Ranges, the Richmond, Tararua and Rimutaka Ranges, the Central Plateau, and around Mt Egmont. Brief dustings of snow were also reported in the ranges of Motueka and Northland. In mid-August, a second polar outbreak brought heavy snow to unusually low levels across eastern and alpine areas of the South Island, as well as to suburban Wellington. Snow also fell across the lower North Island, with flurries in unusual locations further north, such as Auckland and Northland. Numerous August (as well as all-time) low temperature records were broken between 14 – 17 August. And torrential rain caused a State of Emergency to be declared in Nelson on 14 December, following record- breaking rainfall, widespread flooding and land slips. Annual mean sea level pressures were much higher than usual well to the east of the North Island in 2011, producing more northeasterly winds than usual over northern and central New Zealand. -

Nohoanga Site Information Sheet Waianakarua (Glencoe Reserve)

Updated August 2020 NOHOANGA SITE INFORMATION SHEET WAIANAKARUA (GLENCOE RESERVE), NORTH OTAGO Getting there • The site is just west of Herbert, approximately 30 minutes south of Oamaru. • From Herbert township on State Highway 1, take Cullen Street to Monk Street, then head south to the end of Monk Street and west onto Glencoe Road. • Follow Glencoe Road, it will run onto Tulliemet Road. • Turn left at Camp Iona and follow the gravel road to the nohoanga site which is within the Department of Conservation camping site. The nohoanga site is on the right side of the entrance. • There is signage on site. For further information phone 0800 NOHOANGA or email [email protected] Page 1 of 5 Updated August 2020 Physical description • The nohoanga is not as large as other sites, but is flat and well-sheltered. • The site is an excellent area for camping. Vehicle access and parking • The site has excellent two wheel drive vehicle access right onto the site and is suitable for caravan and campervan use. • All vehicles should be parked on the nohoanga site and not the adjacent public camping area. Facilities and services • Nohoanga site users have permission to use the toilets and water located on the adjoining Department of Conservation camping area. As these facilities are shared with the public, always show consideration in accordance with the general information sheet. • The are no other facilities on the Waianakarua (Glencoe Reserve) nohoanga site. Site users need to provide their own shower facilities. • Water should be boiled at all times. • There is limited cell phone reception on this site. -

Council Agenda Extraordinary Meeting

MASTERTON DISTRICT COUNCIL COUNCIL AGENDA EXTRAORDINARY MEETING MONDAY 30 AUGUST 2021 4.30PM MEMBERSHIP Her Worship (Chairperson) Cr G Caffell Cr B Gare Cr D Holmes Cr B Johnson Cr G McClymont Cr F Mailman Cr T Nelson Cr T Nixon Cr C Peterson Cr S Ryan Noce is given that an extraordinary meeng of the Masterton District Council will be held at 4.30pm on Monday 30 August 2021 . RECOMMENDATIONS IN REPORTS ARE NOT TO BE CONSTRUED AS COUNCIL POLICY UNTIL ADOPTED 26 August 2021 Values 1. Public interest: members will serve the best interests of the people within the Masterton district and discharge their duties conscientiously, to the best of their ability. 2. Public trust: members, in order to foster community confidence and trust in their Council, will work together constructively and uphold the values of honesty, integrity, accountability and transparency. 3. Ethical behaviour: members will not place themselves in situations where their honesty and integrity may be questioned, will not behave improperly and will avoid the appearance of any such behaviour. 4. Objectivity: members will make decisions on merit; including appointments, awarding contracts, and recommending individuals for rewards or benefits. 5. Respect for others: will treat people, including other members, with respect and courtesy, regardless of their ethnicity, age, religion, gender, sexual orientation, or disability. Members will respect the impartiality and integrity of Council staff. 6. Duty to uphold the law: members will comply with all legislative requirements applying to their role, abide by this Code, and act in accordance with the trust placed in them by the public. -

Waste Disposal Facilities

Waste Disposal Facilities S Russell Landfill ' 0 Ahipara Landfill ° Far North District Council 5 3 Far North District Council Claris Landfill - Auckland City Council Redvale Landfill Waste Management New Zealand Limited Whitford Landfill - Waste Disposal Services Tirohia Landfill - HG Leach & Co. Limited Hampton Downs Landfill - EnviroWaste Services Ltd Waiapu Landfill Gisborne District Council Tokoroa Landfill Burma Road Landfill South Waikato District Council Whakatane District Council Waitomo District Landfill Rotorua District Sanitary Landfill Waitomo District Council Rotorua District Council Broadlands Road Landfill Taupo District Council Colson Road Landfill New Plymouth District Council Ruapehu District Landfill Ruapehu District Council New Zealand Wairoa - Wairoa District Council Waiouru Landfill - New Zealand Defence Force Chatham Omarunui Landfill Hastings District Council Islands Bonny Glenn Midwest Disposal Limited Central Hawke's Bay District Landfill S ' Central Hawke's Bay District Council 0 ° 0 4 Levin Landfill Pongaroa Landfill Seafloor data provided by NIWA Horowhenua District Council Tararua District Council Eves Valley Landfill Tasman District Council Spicer Valley Eketahuna Landfill Porirua City Council Silverstream Landfill Tararua District Council Karamea Refuse Tip Hutt City Council Buller District Council Wainuiomata Landfill - Hutt City Council Southern Landfill - Wellington City Council York Valley Landfill Marlborough Regional Landfill (Bluegums) Nelson City Council Marlborough District Council Maruia / Springs -

Development of Bird Population Monitoring in New Zealand: Proceedings of a Workshop

Development of Bird Population Monitoring in New Zealand: Proceedings of a Workshop Eric B. Spurr Landcare Research C. John Ralph US Forest Service Landcare Research Science Series No. 32 Development of Bird Population Monitoring in New Zealand: Proceedings of a Workshop Eric B. Spurr Landcare Research C. John Ralph US Forest Service (Compilers) Landcare Research Science Series No. 32 Lincoln, Canterbury, New Zealand 2006 © Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd 2006 This information may be copied or reproduced electronically and distributed to others without limitation, provided Landcare Research New Zealand Limited is acknowledged as the source of information. Under no circumstances may a charge be made for this information without the express permission of Landcare Research New Zealand Limited. CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Spurr, E.B. Development of bird population monitoring in New Zealand: proceedings of a workshop / Eric B. Spurr and C. John Ralph, compilers – Lincoln, N.Z. : Manaaki Whenua Press, 2006. (Landcare Research Science series, ISSN 1172-269X; no. 32) ISBN-13: 978-0-478-09384-1 ISBN-10: 0-478-09384-5 1. Bird populations – New Zealand. 2. Birds – Monitoring – New Zealand. 3. Birds – Counting – New Zealand. I. Spurr, E.B. II. Series. UDC 598.2(931):574.3.087.001.42 Edited by Christine Bezar Layout design Typesetting by Wendy Weller Cover design by Anouk Wanrooy Published by Manaaki Whenua Press, Landcare Research, PO Box 40, Lincoln 7640, New Zealand. 3 Contents Summary ..............................................................................................................................4 -

OPPORTUNITIES Intergraph 2010 NEW ZEALAND 14 - 15 SEPTEMBER USERS’ COMMUNITY CONFERENCE

INTERGRAPH 2010 NEW ZEALAND USERS’ COMMUNITY CONFERENCE 14-15 September 2010 Rendezvous Hotel, Auckland86% Loaded A WORLD OF OPPORTUNITIES INTERGRAPH 2010 NEW ZEALAND 14 - 15 SEPTEMBER USERS’ COMMUNITY CONFERENCE DAY ONE KEYNOTES Time Keynotes 8.30am Registration Opens 9.30am Welcome Address Government Keynote 9.45am David Shearer, New Zealand Labour Party Spokesperson for Research, Science and Technology and Associate Spokesperson for the Environment 10.30am Morning Tea Intergraph Corporate Keynote 10.50am Andrew Munro, General Manager, Southeast Asia, Utilities, Communications, Government and Transportation, Intergraph New Zealand Geospatial Office Keynote 11.35am Kevin Sweeney, Geospatial Custodian, New Zealand Geospatial Office, Land Information New Zealand General Sales Update 12.20pm Richard Vernon, Business Development Manager, Intergraph 12.50pm Lunch DAY ONE SESSIONS Time Government and Transportation Utilities and Communications SDI Portal G/Technology Roadmap 1.50pm Robert Parsons, Intergraph Simon Feneyhough, Intergraph G/Technology 10.1 Upgrade Customer Presentation 2.20pm Chris Axford, Orion NZ Limited and Adrian Buddle, Southland District Council Martin Byrne, Intergraph Spatial Roadmap Fibre Update 2:50pm Anton van Wyk, Intergraph Ken Mathers, Intergraph 3.20pm Afternoon Tea A Checklist of Good Practices Customer Presentations 3.40pm Bryan Clarke and Shelley Sutcliffe, Lauren Scott and Nimisha Patel, Top Energy Christchurch City Council Customer Presentation SmartGrid 4.20pm Kyle Dow, Christchurch City Council Simon Ferneyhough, -

Waitaki Short and Long-Term Rental Accommodation

Waitaki short and long-term rental accommodation Building Better Homes, Towns & Cities: Thriving Regions Working Paper: 20-08b August 2020 Malcolm Campbell1, Nick Taylor2 & Mike Mackay3 1. The University of Canterbury 2. Nick Taylor and Associates 3. AgResearch Limited ISSN (online) 2624-0750 Title Waitaki Short and Long-Term Rental Accommodation ISSN (online) 2624-0750 Author(s) Malcolm Campbell, Nick Taylor and Mike Mackay Series Working Paper 20-08b Author Contact Details Malcolm Campbell The University of Canterbury [email protected] Nick Taylor Nick Taylor and Associates [email protected] Mike Mackay AgResearch [email protected] Acknowledgements We acknowledge funding from the Building Better Homes, Towns and Cities National Science Challenge. We also acknowledge collaboration with the Waitaki Housing Task Force and Safer Waitaki and the questions they have raised around housing in the district. None of these organisations is responsible for the information in this paper. Every effort has been made to ensure the soundness and accuracy of the opinions and information expressed in it. While we consider statements in the report are correct, no liability is accepted for any incorrect statement or information. Recommended citation Campbell, M., Taylor, N. and Mackay, M. 2020. Waitaki Short and Long-Term Rental National Science Challenge: Building Better Homes, Towns and Cities: Ko ngā wā kāinga hei whakamāhorahora (BBHTC). Wellington, New Zealand. https://www.buildingbetter.nz/research/thriving_regions.html © 2020 Building Better Homes, Towns and Cities National Science Challenge and the authors. Short extracts, not exceeding two paragraphs, may be quoted provided clear attribution is given. -

Invercargill CITY COUNCIL

Invercargill CITY COUNCIL NOTICE OF MEETING Notice is hereby given of the Meeting of the Regulatory Services Committee to be held in the Council Chamber, First Floor, Civic Administration Building, 101 Esk Street, Invercargill on Tuesday 2 July 2013 at 4.00 pm His Worship the Mayor Mr TR Shadbolt JP Cr 0 J Ludlow (Chair) Cr G J Sycamore (Deputy Chair) CrC G Dean CrA G Dennis Cr I L Esler CrG D Lewis Cr IR Pottinger Cr L S Thomas EIRWEN HARRIS MANAGER, SECRETARIAL SERVICES Finance and Corporate Services Directorate Civic Administration Building • 101 Esk Street • Private Bag 90104 Invercargill • 9840 • New Zealand DX No. YA90023 • Telephone 032111777. Fax 03 211 1433 AGENDA Page 1. APOLOGIES Cr GJ Sycamore. 2. PUBLIC FORUM 3. SUBMISSIONS TO INVERCARGILL CITY COUNCIL BYLAW I 2013/2 − KEEPING OF ANIMALS, POULTRY AND BEES Appendix 1 5 Appendix 2 7 Appendix 3 105 Appendix 4 133 4 MONITORING OF SERVICE PERFORMANCES 141 4.1 LEVELS OF SERVICE 142 4.1.1 Animal Control 143 4.1.2 Building Consents 144 4.1.3 Compliance 145 4.1.4 Environmental Health 145 4.1.5 Resource Management 148 4.1.6 Valuation 5. MONITORING OF FINANCIAL PERFORMANCES 149 5.1 DIRECTORATE OVERVIEW 149 5.2 ADMINISTRATION 149 5.3 ANIMAL CONTROL 5.4 ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH 150 5.5 BUILDING 150 5.6 LIQUOR LICENSING 150 5.7 VALUATION 150 5.8 COMPLIANCE 150 5.9 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT 150 5.10 FINANCIAL SUMMARY 151 6 ACTIVITY PLAN REVIEW N/A. 7 DEVELOPMENT OF POLICIES/BYLAWS N/A. -

CB List by Zone and Council

ZONE COUNCIL COMMUNITY BOARD 1 Far North District Council Te Hiku Bay of Islands-Whangaroa Kaikohe-Hokianga 2 Matamata-Piako District Council Matamata Morrinsville Te Aroha Opotiki District Council Coast Otorohanga District Council Kawhia Otorohanga Rotorua District Council Rotorua Lakes South Waikato District Council Tirau (names only – no contact details) Taupo District Council Turangi- Tongariro Thames-Coromandel District Council Coromandel-Colville Mercury Bay Tairua-Pauanui Thames Whangamata Waikato District Council Huntly Community Board Ngaruawahia Community Board Onewhero -Tuakau Community Board Raglan Community Board Taupiri Community Board Waipa District Council Cambridge (names only – no contact details) Te Awamutu (names only – no contact details) Western Bay of Plenty District Council Katikati Community Board Maketu Community Board Omokoroa Community Board Te Puke Community Board Waihi Beach Community Board Whakatane District Council Murupara Ohope Beach Rangitaiki Taneatua Whakatane 3 Hastings District Council Rural Community Board Horowhenua District Council Foxton New Plymouth District Council Clifton Inglewood Kaitake Waitara Rangitikei District Council Ratana Community Board Taihape Community Board Ruapehu District Council National Park Waimarino-Waiouru South Taranaki District Council Egmont Plains Eltham Hawera-Normanby Patea Tararua District Council Dannevirke Eketahuna Wanganui District Council Wanganui Rural (go to ‘about council/community board’) 4 Hutt City Council Eastbourne Community Board Petone Community Board