A Historical Demography of the Headwaters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chartbook, 2018 Update Growth by Region and Practice, 2013–2018

New York PCMH Chartbook, 2018 Update Growth by Region and Practice, 2013–2018 Introduction This chartbook accompanies a UHF issue brief (Patient-Centered Medical Homes in New York, 2018 Update: Drivers of Growth and Challenges for the Future) reviewing broad trends in the adoption of the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) model in New York, noting the remarkable growth in the number of PCMH clinicians between 2017 and 2018—and the contribution of Performing Provider Systems (PPSs) participating in the state’s Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program to that growth. Additionally, the brief describes variation in PCMH adoption by region and type of primary care practice. This chartbook more fully describes that variation. Data Sources The Office of Quality and Patient Safety (OQPS) within the New York State Department of Health (DOH) receives monthly data files from the National Council on Quality Assurance (NCQA) with information on all practices in New York State that have achieved NCQA PCMH recognition, and on the clinical staff (physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician’s assistants) working there. Each year for the past six years, OQPS has shared some of that information with UHF, which then analyzes the adoption of the PCMH model by region and practice type. The Regions As part of a 2015 initiative, the DOH divided the state into 11 regions (see Exhibit 1), funding regional planning agencies (Population Health Improvement Programs, or PHIPs) to develop plans for improving the health of their residents. Before 2015, UHF used New York’s insurance rating regions to analyze PCMH growth; since then we have used the PHIP regions. -

Welcome to The

Welcome to the June 3, 2015 8:00 am — 1:00 pm at the The Hayloft at Moonshine Farm* 6615 Buneo Rd. Port Leyden, NY 13343 Organized and hosted by the Lewis Sponsored by 5 Finger Lakes Lake 1:00 - 5:00 PM and Jefferson County Soil and Water Ontario Watershed Protection Afternoon Field Trip Conservation Districts, NYS Tug Hill Alliance Counties: Lewis, Jefferson, Sponsored by the Commission and the New York State Herkimer, Oneida and Hamilton Department of Environmental Beaver River Advisory Council Conservation Region 6. 8:00 am - 8:20 am Sign in and Refreshments 8:20 am - 8:30 am Welcome and Introduction ~ Nichelle Billhardt, Lewis County Soil and Water Conservation District Morning Session Invasive Species Watercraft Inspection Program ~ Dr. Eric Holmlund, Watershed Stewardship Program 8:30 am - 9:20 am at the ADK Watershed Institute of Paul Smith’s College Project Updates ~ Jennifer Harvill, NYS Tug Hill Commission; Emily Sheridan, NYS DEC; Frank Pace, 9:20 am - 9:50 am Lewis County Eco Dev & Planning; Mike Lumbis, City of Watertown Planning and others Community Resiliency & Green Infrastructure - Green Innovation Grant Program ~ Tana Bigelow, 9:50 am - 10:40 am Green Infrastructure Coordinator, Environmental Facilities Corporation 10:40 am - 10:55 am Break Stormwater MS4 Update ~ Christine Watkins, Jefferson County SWCD & Katie Malinowski, NYS Tug 10:55 am - 11:10 am Hill Commission Nutrient Management 101 ~ Karl Czymmek, Nutrient/CAFO/Environmental Management, Cornell 11:10 am - Noon University Noon Lunch - Soup, Salad, Wraps and Deli -

Regional Planning Consortium QUARTER THREE UPDATE JULY 1 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 Table of Contents

Regional Planning Consortium QUARTER THREE UPDATE JULY 1 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 Table of Contents RPC Mission & Purpose 2020 RPC Areas of Focus ◦ VBP/Managed Care: PC Integration ◦ SDOH/Care Transitions & Co- Occurring Integration ◦ Peer/Behavioral Health Workforce ◦ Children & Families Capital Region Central NY Finger Lakes Long Island Mid-Hudson Mohawk Valley North Country Southern Tier Tug Hill Western NY 2 RPC Mission & Purpose Who We Are: The Regional Planning Consortium (RPC) is a network of 11 regional boards, community stakeholders, and Managed Care Organizations that work closely with our State partners to guide behavioral health policy in the regions to problem-solve and develop lasting solutions to service delivery challenges. RPC Mission Statement: The RPC is where collaboration, problem solving and system improvements for the integration of mental health, addiction treatment services and physical healthcare can occur in a way that is data informed, person and family centered, cost efficient and results in improved overall health for adults and children in our communities. About this Report: The content of this Report targets Quarter 3 (Q3) (July 1 – September 30, 2020) activities conducted by the rest-of-state RPC by Region. Click HERE to return to Table of Contents 3 2020 RPC Areas of Focus In Q3, from a statewide perspective, the RPC continued to develop our four Areas of Focus in 2020. In cooperation with the impactful work occurring within our Boards across the state, common statewide drivers continue to evolve and the RPC -

The Roads Less Traveled: Minimum Maintenance Roads April 2017

ISSUE PAPER SERIES The Roads Less Traveled: Minimum Maintenance Roads April 2017 NEW YORK STATE TUG HILL COMMISSION DULLES STATE OFFICE BUILDING · 317 WASHINGTON STREET · WATERTOWN, NY 13601 · (315) 785-2380 · WWW.TUGHILL.ORG The Tug Hill Commission Technical and Issue Paper Series are designed to help local officials and citizens in the Tug Hill region and other rural parts of New York State. The Tech- nical Paper Series provides guidance on procedures based on questions frequently received by the Commis- sion. The Issue Paper Series pro- vides background on key issues facing the region without taking advocacy positions. Other papers in each se- ries are available from the Tug Hill Commission. Please call us or vis- it our website for more information. The Roads Less Traveled: Minimum Maintenance Roads Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 What are minimum maintenance roads? .................................................................................................... 1 What is the legal status of minimum maintenance road designations? .................................................... 2 What does the proposed legislation do?..................................................................................................... 3 What does minimum maintenance mean? ................................................................................................. 3 What is the difference between -

Tug Hill Invasive Species Prevention Zone (ISPZ) SLELO-PRISM Early Detection Surveillance

St. Lawrence Eastern Lake Ontario Partnership for Regional Invasive Species Management 2016 Field Survey Tug Hill Invasive Species Prevention Zone (ISPZ) SLELO-PRISM Early Detection Surveillance August 9th, 10th, 11th, and 15th, 2016 Report prepared by Ashley Gingeleski and Ben Hansknecht on August 26th, 2016 Figure 1. Picture of Tug Hill ISPZ at Site 085. Photo by Ashley Gingeleski. Introduction and Background1 New York State's Tug Hill Region is a 2,100 square mile area situated between Eastern Lake Ontario and the Black River Valley, and includes lands in Jefferson, Lewis, Oneida and Oswego counties. The largely undeveloped area includes important wetland and forested habitats, as well as an abundance of ponds and lakes. Numerous streams and rivers have their headwaters located within the Tug Hill, and Tug Hill's watersheds are important sources of clean water for Oneida Lake and Lake Ontario in addition to themselves providing high-quality aquatic and riparian habitats (Figure 1). Within the larger Tug Hill region lies the Tug Hill Core Forest, comprised of nearly 150,000 acres of nearly contiguous forested lands. This large forested tract provides a variety of recreational opportunities, and managed forestry operations on both public and privately held lands, provides employment and helps support the area's rural economy. The core forest also provides valuable habitat for a variety of game species, as well as 29 rare animals and 70 rare plant species. The Tug Hill Core Forest remains an area dominated by native species with relatively little impacts from many invasive species. Because of this, an Invasive Species Prevention Zone (ISPZ) was established to monitor and prevent the establishment of high-priority invasive species within the Tug Hill Core Forest (Figure 2). -

Welcome to Lewis County the Adirondacks Tug Hill Region!

Welcome to Lewis County the Adirondacks Tug Hill Region! Lewis County is one of two counties in New York categorized “ru- ral,” with nearly 20% of the land being used for agriculture. They are proud to claim that there are more cows in Lewis County than people—over 28,000 cows and approximately 27,000 people—and this has probably been true for a long, long time. The area also ac- counts for 13% of the maple syrup produced in New York State— nearly 29,000 gallons! Lewis County has unique geography. In a drive of 30 miles you can travel from the Tug Hill Plateau, home of the greatest snow fall in the eastern United States, through the Black River Valley’s fertile farm lands, and into the western edge of the Adirondack Mountains. In a short drive you will find over 500 miles of snowmobile trails, the only permitted ATV trail system in the state, and ample places to ski, horse- back ride, bike, canoe, kayak, fish, and hunt. We invite you to stray a little from the beaten path and visit us here in the Adirondacks Tug Hill Region. Averaging about 200 inches of snow annually, Lewis County is the place for winter enthusiasts! This is snowmobile paradise as there are over 600 miles of trails. Lake-effect snowstorms cover this area in a canvas of white, waiting to capture the traces of your winter adventure. The American Maple Museum in downtown Croghan conducts demonstrations of techniques used to produce this syrup. Beyond the wet muddy springs are warm, breezy summers, and crisp, fresh autumns— making Lewis County a great place to ride! Hundreds of miles of trails and off-season roads offer a different terrain for every preference. -

Soils in Tug Hill, NY

Acknowledgements The Cornell Team would like to thank the following individu- als, agencies, and organizations for their advice, assistance, and expertise: Linda Garrett, Tug Hill Tomorrow Land Trust; Bob Quinn, SUNY Environmental School of Foresty; John Bartow, Tug Hill Commission; Katie Malinowski, Tug Hill Commission; Phil Street, Tug Hill Commission; Michelle Peach, The Nature Conservancy; Jonathan Sinker; Dr. Charles Smith, Depart- ment of Natural Resources, Cornell University; Steve Smith, IRIS, Cornell University; David Gross, Department of Natural Resources, Cornell University; George Franz and Dr. Richard Booth, Department of City and Regional Planning, Cornell University; Jeff Milder, PhD Candidate, Department of Natu- ral Resources, Cornell University; Dr. Kent Messer, Applied Economics and Management, Cornell University; Melissa Reichert and Michael Liu, Green Mountain & Finger Lakes Pictured, L-R: Sophie Mintier, Josh Lathan, James Cornwell, Chelsey National Forests; Michael Bourcy, Jefferson County Planning Norton, Ole Amundsen III, Aaron Beaudette, Julia Svard, Heather Mar- Department; Ramona Salmon, Lewis County Real Property ciniec, Evan Duvall, Ann Dillemuth, Conor Semler, Jetal Bhakta, Aatisha Services; Guy Sassaman, Oneida County Finance Depar- Singh, Himalay Verma, Camille Barchers, Jessica Daniels. ment; Charlotte Beagle; Jordan Suter, Applied Economics and Management Department, Cornell University; Patricia Box, Town of Lee Assessors Office; Mark Twentyman, New York State Office of Real Property Services; Nicholas Conrad, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation; William Johnson, New York State Office of Cyber Security and Critical Infrastructure Coordination; Christina Croll, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preserva- tion. Foreword December 2006 Dear Friends: The City and Regional Planning Department at Cornell University has helped nonprofit organizations overcome planning challenges with technical assistance provided in client-based workshops. -

Do You Own Forest Land?

Cornell Cooperative Extension and New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Master Forest Owner Volunteers - DIVISION OF LANDS AND FORESTS - Do you own forest land? Call any of the following Cornell Cooperative Extension offices for Website: www.dec.state.ny.us/website/dlf educational assistance with your woodlot: County ........... Phone County ...........Phone REGION 1 (SUFFOLK, NASSAU ) As a forest owner, are you ... Albany .............518-765-3500 Onondaga .......315-424-9485 SUNY Stony Brook...... 631-444-0285 Allegany ..........716-699-2377 Ontario ............585-394-3977 Broome............607-772-8954 Orange............845-344-1234 REGION 2 (MANHATTAN, BRONX, QUEENS, BROOKLYN, STATEN Prepared Cattaraugus.....716-699-2377 Orleans ...........585-589-5561 ISLAND) Cayuga............315-255-1183 Oswego...........315-963-7286 Long Island City........... 718-482-4942 Chautauqua.....716-664-9502 Otsego ............607-547-2536 Knowledgeable Chenango........607-334-5841 Rensselaer......518-272-4210 REGION 3 (DUTCHESS, ORANGE, PUTNAM, ROCKLAND, SULLIVAN, Columbia.........518-828-3346 St. Lawrence...315-379-9192 ULSTER, WESTCHESTER) Delaware.........607-865-6531 Saratoga .........518-885-8995 Wappingers Falls......... 845-831-8780 Uncertain Erie..................716-652-5400 Schenectady ...518-372-1622 New Paltz .................... 845-256-3076 Essex .............518-962-4810 Schoharie........518-234-4303 Franklin ...........518-483-7403 Schuyler..........607-535-7161 REGION 4 (ALBANY, COLUMBIA, DELAWARE, GREENE, MONTGOMERY, -

Fish Creek East Branch

wild and scenic river study november 1982 FISH CREEK EAST BRANCH NEW YORK WILD AND SCENIC RIVER STUDY East Branch of Fish Creek New York Denver Service Center North Atlantic Region National Park Service United States Department of the Interior CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v SUMMARY OF FINDINGS AND CONCULSIONS 1 PURPOSES OF THE WILD AND SCENIC RIVERS ACT AND THE STUDY 4 STUDY BACKGROUND 5 Past Studies of the East Branch 5 Authorization of the Fish Creek Study 5 CONDUCT OF THE STUDY/PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT 7 DESCRIPTION OF FISH CREEK STUDY AREA 9 Regional Setting 9 Socioeconimic Overview 9 Landownership and Use 10 Natural and Cultural Attributes 11 FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS 16 Wild and Scenic River Eligibility 16 Suitability for Designation 20 Trends and Potential Changes Along the East Branch 21 Conservation Through State and Local Efforts 24 APPENDIXES 35 A: Classification Criteria for Wild, Scenic, and Recreational River Areas 37 B: Additional Information on Local and State Programs and Legal Authorities 39 C: General Background Information on Resource Management and Land Use Control Techniques 55 D: Public and Agency Comments on the Study 57 REFERENCES CITED 80 STUDY PARTICIPANTS 81 iii MAPS East Branch of Fish Creek Study Area 3 Past Study Recommendations for Eligibility / Classification 6 River Segment Eligibility and Potential Classification 17 TABLES 1. Study Area Town Population 10 2. East Branch of Fish Creek - Segment Length , Eligibility, Values, and Potential Classification 18 3. Major Land Use Control Provisions for Martinsburg, West Turin, and Osceola 26 4. Major Land Use Control Provisions for Lewis and Lee 28 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The National Park Service appreciates assistance received from the staffs of the Tug Hill Commission and the Tug Hill Cooperative Planning Board during this study effort. -

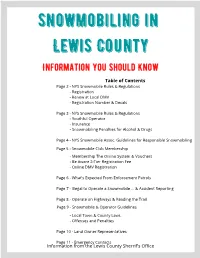

Snowmobile Rules & Regulations - Registration - Renew at Local DMV - Registration Number & Decals

Snowmobiling in Lewis County Information You Should Know Table of Contents Page 2 - NYS Snowmobile Rules & Regulations - Registration - Renew at Local DMV - Registration Number & Decals Page 3 - NYS Snowmobile Rules & Regulations - Youthful Operator - Insurance - Snowmobiling Penalties for Alcohol & Drugs Page 4 - NYS Snowmobile Assoc. Guidelines for Responsible Snowmobiling Page 5 - Snowmobile Club Membership - Membership The Online System & Vouchers - Be Aware 2-Tier Registration Fee - Online DMV Registration Page 6 - What's Expected From Enforcement Patrols Page 7 - Illegal to Operate a Snowmobile ... & Accident Reporting Page 8 - Operate on Highways & Reading the Trail Page 9 - Snowmobile & Operator Guidelines - Local Town & County Laws - Offenses and Penalties Page 10 - Land Owner Representatives Page 11 - Emergency Contacts Information from the Lewis County Sherrif's Office NYS Snowmobile Rules & Regulations Registration Each snowmobile operated in New York State must be properly registered, unless it is used only on its owner' property. If you are NOT a New York State Resident and your snowmobile's properly registered in another state, province, or country, your snowmobile must still be registered in New York State and the NY DMV yearly validation sticker and out of state registration numbers must be displayed while operating in New York State. If the snowmobile is not registered in any state, province, or country, you must register it in New York State and properly display the NY registration numbers and DMV yearly validation sticker. In cooperation with the Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, the Department of Motor Vehicles has been designated to provide all New York State snowmobile registrations. These are available through all DMV District Offices and are valid for one year. -

Land Ownership and Protected Lands in the Tug Hill Region November

Land Ownership and Protected Lands in the Tug Hill Region November 2015 TUG HILL COMMISSION ISSUE PAPER SERIES TUG HILL COMMISSION Dulles State Office Building 317 Washington Street Watertown, New York 13601-3782 315-785-2380/2570 or 1-888-785-2380 fax: 315-785-2574 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.tughill.org LAND OWNERSHIP AND PROTECTED LANDS IN THE TUG HILL REGION Introduction Protected lands are lands kept in their relatively natural forms for many purposes such as protecting open space and water quality, recreation, wildlife management, forest management or a variety of ecosystem services. These lands can be owned by a private individual or can be owned publicly. Protection can be provided in the form of fee (outright) ownership or through a conservation easement. Public agencies like the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) or private not-for-profits such as The Nature Conservancy, The Conservation Fund or local land trusts like Tug Hill Tomorrow Land Trust (THTLT) can own protected land or hold conservation easements. The purpose of this paper is to identify and describe protected lands in the Tug Hill region and to provide a baseline of the quantity of protected lands in the region. For the purposes of this paper, protected land will be considered property owned outright (in fee) by a public entity or a private land conservation organization for conservation purposes. It will also be considered protected land if a conservation easement exists for the property, which is held by a public agency or private organization in perpetuity as a third party, with the underlying ownership maintained by a private landowner. -

Air Pollution Impacts in the Tug Hill Region

Acid Deposition Impacts in the Tug Hill Region December 2009 TUG HILL COMMISSION ISSUE PAPER SERIES TUG HILL COMMISSION Dulles State Office Building 317 Washington Street Watertown, New York 13601-3782 315-785-2380/2570 or 1-888-785-2380 ~ fax: 315-785-2574 e-mail: [email protected] website: http://www.tughill.org Acid Deposition Impacts in the Tug Hill Region What is Acid Deposition? Acid deposition, sometimes referred to as ‘acid rain,’ is a result of chemical reactions between sulfur and nitrous oxides with other substances in the atmosphere. The reactions convert these pollutants into weak acids, which may return to earth as components of rain, fog, snow or dry particles. Acid deposition is just one type of atmospheric deposition, which can also include substances such as mercury, pesticides, and persistent toxic compounds that accumulate in the food chains of lakes and streams. Where Does Acid Deposition Come From? The pollutants that cause acid deposition are mainly a result of the burning of fossil fuels such as oil and coal. The United States discharges nearly 50 million tons of sulfur and nitrogen oxides every year into the air. Power plants burning coal, oil and natural gas account for about 70 percent of the sulfur dioxide emissions in the United States. Cars and trucks, coal-burning power plants and industrial boilers and heaters account for most of the nitrogen oxide emissions. Most of these sources are located west of New York State, with combustion products carried east with prevailing winds. What Are The Effects of Acid Deposition? Acid deposition has caused lakes and streams to become acidic and unsuitable for many fish, damaged forests, and caused deterioration of many man-made structures worldwide.