Issue 2: the Traffickers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcast Media Intervention in Mental Health Challenge in Edo State, Nigeria

O. S. Omoera & P. Aihevba– Broadcast Media Intervention in Mental Health Challenge Medical Anthropology 439 - 452 Broadcast Media Intervention in Mental Health Challenge in Edo State, Nigeria Osakue Stevenson Omoera1 and Peter Aihevba2 Abstract In most communities, especially in Africa, people with mental health challenges are denigrated; the society is not sympathetic with sufferers of mental illness. A lot of issues can trigger mental illness. These can be stress (economic stress, social stress, educational stress, etc); hereditary factors; war and aggression; rape; spiritual factors, to mention a few. Therefore, there is the need for understanding and awareness creation among the people as one of the ways of addressing the problem. Methodologically, this study deploys analytical, observation and interview techniques. In doing this, it uses the Edo State, Nigeria scenario to critically reflect, albeit preliminarily, on the interventionist role the broadcast media have played/are playing/should play in creating awareness and providing support systems for mentally challenged persons in urban and rural centres in Nigeria. The study argues that television and radio media are very innovative and their innovativeness can be deployed in the area of putting mental health issue in the public discourse and calling for action. This is because, as modern means of mass communication, radio and television engender a technologically negotiated reaching-out or dissemination of information which naturally flows to all manner of persons regardless of -

Country Advice Nigeria Nigeria – NGA40366– Political Assassinations – People’S Democratic Party (PDP) – Passports 29 May 2012

Country Advice Nigeria Nigeria – NGA40366– Political Assassinations – People’s Democratic Party (PDP) – Passports 29 May 2012 1. Deleted. 2. Please provide general information relating to the Egor Local Government area in Benin City, including any information relating to political assassinations, other suspicious murders, corruption, connections to criminal gangs etc. The Local Government area of Egor is located within Edo State, in central-southern Nigeria. Its headquarters are in the town of Uselu, which according to Google Maps is approximately 10.2 kilometres from Benin City.1 The last census from 2006 estimated the population of the Egor Local Government area to be 339,899.2 It is noted that while Benin City does not fall within the Egor Local Government area3, given the areas proximity to the capital city many sources that discuss Egor Local Government area also make reference to Benin City. Figure 1: Map Showing Local Government Areas of Edo State, Nigeria4 Egor Local Government Area Uselu Benin City 1 Google Maps n.d., Uselu to Benin City <http://maps.google.com/maps?saddr=benin+city&daddr=Uselu,+Benin+City,+Nigeria&hl=en&ll=6.33236,5.62671 7&spn=0.275712,0.393791&sll=6.409056,5.614256&sspn=0.008615,0.012306&geocode=FQi6YAAdctpVACnxrM 95YtNAEDGg31hXwBCqhA%3BFWDLYQAdsKpVAA&mra=ls&t=m&z=12> Accessed 25 May 2012 2 Edo Heritage n.d., Egor <http://edoheritage.com/egor.html> Accessed 24 May 2012 3 Benin City falls within the Oredo Local Government area. 4 Nigerian Muse n.d., April 2007 Elections in Nigeria <http://www.nigerianmuse.com/20071205131228zg/nm- projects/electoral-reform-project/star-information-april-2007-elections-in-nigeria-the-case-of-edo-gubernatorial- elections/> Accessed 28 May 2012 Page 1 of 10 Reports were located of three political assassinations in Benin City in 2005 and 2000, two of which involved PDP members. -

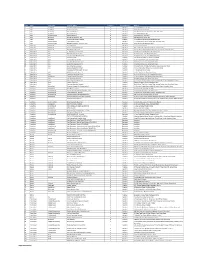

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address 1 Abia AbaNorth John Okorie Memorial Hospital D Medical 12-14, Akabogu Street, Aba 2 Abia AbaNorth Springs Clinic, Aba D Medical 18, Scotland Crescent, Aba 3 Abia AbaSouth Simeone Hospital D Medical 2/4, Abagana Street, Umuocham, Aba, ABia State. 4 Abia AbaNorth Mendel Hospital D Medical 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA. 5 Abia UmuahiaNorth Obioma Hospital D Medical 21, School Road, Umuahia 6 Abia AbaNorth New Era Hospital Ltd, Aba D Medical 212/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba 7 Abia AbaNorth Living Word Mission Hospital D Medical 7, Umuocham Road, off Aba-Owerri Rd. Aba 8 Abia UmuahiaNorth Uche Medicare Clinic D Medical C 25 World Bank Housing Estate,Umuahia,Abia state 9 Abia UmuahiaSouth MEDPLUS LIMITED - Umuahia Abia C Pharmacy Shop 18, Shoprite Mall Abia State. 10 Adamawa YolaNorth Peace Hospital D Medical 2, Luggere Street, Yola 11 Adamawa YolaNorth Da'ama Specialist Hospital D Medical 70/72, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola, Adamawa State. 12 Adamawa YolaSouth New Boshang Hospital D Medical Ngurore Road, Karewa G.R.A Extension, Jimeta Yola, Adamawa State. 13 Akwa Ibom Uyo St. Athanasius' Hospital,Ltd D Medical 1,Ufeh Street, Fed H/Estate, Abak Road, Uyo. 14 Akwa Ibom Uyo Mfonabasi Medical Centre D Medical 10, Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 15 Akwa Ibom Uyo Gateway Clinic And Maternity D Medical 15, Okon Essien Lane, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. 16 Akwa Ibom Uyo Fulcare Hospital C Medical 15B, Ekpanya Street, Uyo Akwa Ibom State. 17 Akwa Ibom Uyo Unwana Family Hospital D Medical 16, Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 18 Akwa Ibom Uyo Good Health Specialist Clinic D Medical 26, Udobio Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. -

Human Trafficking Between Nigeria and the UK: Addressing a Shared Challenge

Human Trafficking Between Nigeria and the UK: Addressing a Shared Challenge Cover Photo: Devatop Centre for Africa Development Team with Delegation in Abuja on the 16 February 2018 Credit: Devatop Centre for Africa Development Contents Introduction 2 The Journey to Europe 4 The UK and Trafficking from Nigeria 7 The Challenges of Returning 9 Responses and Key Institutions 12 Recommended Approaches to Support Anti - Trafficking Efforts 19 Acknowledgments 2 1 Appendix: Nigeria APPG Visit Itinerary 2 2 1 estimate d that approximately 1 .4 million Introduction Nigerians, or around 0.7 per cent of the country’s total population , 1 are living in a state of modern In February 2018 , a delegation of the All - Party slavery. Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Nigeria visited the country on a fact - finding mission to examine Most of those affected are found in Nigeria and initiatives to combat human trafficking from in countries where there is a settled Nigerian Nigeria to the UK , and explore areas of current diaspora . The country’s rapid population growth , and potential cooperation. The visit aimed to a struggling education system and a lack of youth increase UK parliamentary understanding of employment opportunities are contributing human trafficking from Nigeria, to highlight the factors to the problem . issue in both countries , and to further cement According to United Na tions data, Nigeria’s link s between parliamentarians and their population in 2017 was 191 million . 2 By 2050, coun terparts in the National Assembly of the UN projects that that figure will reach over Nigeria. 400 million, behind only India and China . -

Nigeria – Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 22 October 2010 Information on the Followi

Nigeria – Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 22 October 2010 Information on the following: 1. The similarities (if any) between Urhobo (alternatively “Sobo”) and Itsekiri (alt. “Isekiri”; “Ishekiri”; etc.) language; 2. The similarities (if any) between Urhobo and Itsekiri ethnicities/cultures/customs; 3. The distribution of Urhobo and Itsekiri populations; including whether these groups live in the same towns/regions of Nigeria; 4. Whether there is any information on whether Itsekiri speakers can or do speak Urhobo, and vice versa. 5. Whether there is conflict/co-operation between Urhobo and Itsekiri people (groups or individuals), and to what extent. A page on the Delta State Tourism website states: “There are five ethnic groups in Delta State, namely Anioma, Ijaw, Isoko, Itsekiri and Urhobo. Deltans speak a variety of languages and dialects but have nearly identical customs, culture and occupations. These are easily identified in the courts of most traditional rulers across the state.” (Delta State Tourism (undated) Delta State: The Big Heart) An entry on the Urhobo in The Peoples of Africa – An Ethnohistorical Dictionary states: “The Urhobo (Uhrobo, Biotu, and the pejorative Sobo) people live in Bendel State in Nigeria, primarily in the Western and Eastern Urhobo divisions. They are closely related to the neighboring Edo people.” (Olson, James S. (1996) The Peoples of Africa – An Ethnohistorical Dictionary. Westport, Greenwood Press. p.578) A page on the Urhobo Association of New York, New Jersey & Connecticut website, in a paragraph headed “People”, states: “The Urhobo people are located in the present Delta State of Nigeria. -

Access Bank Branches Nationwide

LIST OF ACCESS BANK BRANCHES NATIONWIDE ABUJA Town Address Ademola Adetokunbo Plot 833, Ademola Adetokunbo Crescent, Wuse 2, Abuja. Aminu Kano Plot 1195, Aminu Kano Cresent, Wuse II, Abuja. Asokoro 48, Yakubu Gowon Crescent, Asokoro, Abuja. Garki Plot 1231, Cadastral Zone A03, Garki II District, Abuja. Kubwa Plot 59, Gado Nasko Road, Kubwa, Abuja. National Assembly National Assembly White House Basement, Abuja. Wuse Market 36, Doula Street, Zone 5, Wuse Market. Herbert Macaulay Plot 247, Herbert Macaulay Way Total House Building, Opposite NNPC Tower, Central Business District Abuja. ABIA STATE Town Address Aba 69, Azikiwe Road, Abia. Umuahia 6, Trading/Residential Area (Library Avenue). ADAMAWA STATE Town Address Yola 13/15, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola. AKWA IBOM STATE Town Address Uyo 21/23 Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom. ANAMBRA STATE Town Address Awka 1, Ajekwe Close, Off Enugu-Onitsha Express way, Awka. Nnewi Block 015, Zone 1, Edo-Ezemewi Road, Nnewi. Onitsha 6, New Market Road , Onitsha. BAUCHI STATE Town Address Bauchi 24, Murtala Mohammed Way, Bauchi. BAYELSA STATE Town Address Yenagoa Plot 3, Onopa Commercial Layout, Onopa, Yenagoa. BENUE STATE Town Address Makurdi 5, Ogiri Oko Road, GRA, Makurdi BORNO STATE Town Address Maiduguri Sir Kashim Ibrahim Way, Maiduguri. CROSS RIVER STATE Town Address Calabar 45, Muritala Mohammed Way, Calabar. Access Bank Cash Center Unicem Mfamosing, Calabar DELTA STATE Town Address Asaba 304, Nnebisi, Road, Asaba. Warri 57, Effurun/Sapele Road, Warri. EBONYI STATE Town Address Abakaliki 44, Ogoja Road, Abakaliki. EDO STATE Town Address Benin 45, Akpakpava Street, Benin City, Benin. Sapele Road 164, Opposite NPDC, Sapele Road. -

Delineation of Built-Up Areas Liable to Flood in Yola, Adamawa State, Nigeria Using Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System Technologies

FUTY Journal of the Environment Vol.8 No. 1, June 2014 20 Delineation of Built-up Areas Liable to Flood in Yola, Adamawa State, Nigeria Using Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System Technologies 1Isa, Muhammad Zumo and 2Musa A. A. 1 Dept of Surveying & Geoinformatics, Federal Polytechnic Damaturu, Yobe State, Nigeria 2 Dept of Surveying & Geoinformatics, Modibbo Adama University of Tech Yola Adamawa St. Nigeria 1GSM: 08066011217 2GSM:08036127598 Abstract This study used the techniques of Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System (GIS) to identify the built up areas within Jimeta/Yola town that are liable to flood. Ikonos image and a topographic map covering the study area were used. Built up area was extracted from the image while an elevation model was created from the topographical map. The built up area was overlaid on the elevation model. Those within the flood plain are liable to flood while those outside the floodplain are not liable to flood. The result shows that Jambutu area in Jimeta has the highest risk of flooding; the flooded area covers 12.296 hectares. In Yola, most portion of Damare area is a flood vulnerable area. It covers an area of 1.759 hectares. The total area likely to get flooded in Jimeta/Yola town is 15.636 hectares. Keywords: Built-up area, Flood, Floodplain, Georeference, River Benue, Yola-Jimeta 1.0 Introduction Flooding is one of the numerous natural disasters that affect lives and properties. Over the past decades, the pattern of floods across all continents has been changing, becoming more frequent, intense and unpredictable for local communities, particularly as issues of development and poverty have led more people to live in areas vulnerable to flooding (Dabara, 2012). -

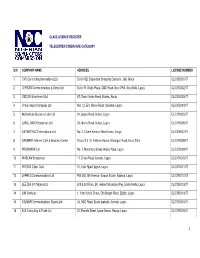

S/N Company Name Address License Number 1 Cvs

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER TELECENTER/CYBERCAFÉ CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/CYB/001/07 2 CHYSAN Communications & Books Ltd Suite 19, Oadis Plaza, CMD Road, Ikosi GRA, Ikosi-Ketu, Lagos CL/CYB/002/07 3 GIDSON Investment Ltd 67, Gado Nasko Road, Kubwa, Abuja CL/CYB/003/07 4 Virtual Impact Company Ltd NO. 12, Eric Moore Road, Surulere, Lagos CL/CYB/004/07 5 Multicellular Business Links Ltd 91, Ijegun Road, Ikotun, Lagos CL/CYB/005/07 6 LAFAL (NIG) Enterprises Ltd 25, Idumu Road, Ikotun, Lagos CL/CYB/006/07 7 DATASTRUCT International Ltd No. 2, Chime Avenue, New Haven, Enugu CL/CYB/007/07 8 SADMART Internet Café & Business Center Shops 9 & 10, Kaltume House, Maiduguri Road, Kano State CL/CYB/008/07 9 PRADMARK Ltd No. 7, Moronfolu Street, Akoka-Yaba, Lagos CL/CYB/009/07 10 WABLAM Enterprises 17, Oriwu Road, Ikorodu, Lagos CL/CYB/010/07 11 FETSAS Cyber Café 10, Isolo Rpad, Ijegun, Lagos CL/CYB/011/07 12 JARRED Communications Ltd Plot 450, 5th Avenue, Gowon Estate, Egbeda, Lagos CL/CYB/012/07 13 LEETDA Int'l Nigeria Ltd 2nd & 3rd Floor, 58, Herbert Macaulay Way, Ebute-Metta, Lagos CL/CYB/013/07 14 JINI Ventures 1, Yomi Ishola Street, Off Ailegun Road, Ejigbo, Lagos CL/CYB/014/07 15 FALMUR Communications Nigeria Ltd 34, NBC Road, Ebute-Ipakodo, Ikorodu, Lagos CL/CYB/015/07 16 KJS Consulting & Trade Ltd 22, Ewenla Street, Iyana-Oworo, Bariga, Lagos CL/CYB/016/07 1 17 Network Excel Company Ltd 62, Akowonjo Road, Shop 13 & 14, Summit Guest House Complex, Egbeda, Lagos CL/CYB/017/07 18 SHEDDY Communications 25B, Irone Avenue, Aguda, Surulere, Lagos CL/CYB/018/07 19 Leader Tech Communications Ltd 7, Gbogan Road, Oshogbo, Osun State CL/CYB/019/07 20 MAGBUS Ventures 1, Owolabi Rabiu Close, Off Isawo Road, Agric, Owutu, Ikorodu, Lagos CL/CYB/020/07 21 Netwrok Packet Standard Co. -

Data Analysis of Land Use Change and Urban and Rural Impacts in Lagos State, Nigeria

data Article Data Analysis of Land Use Change and Urban and Rural Impacts in Lagos State, Nigeria Olalekan O. Onilude 1 and Eric Vaz 2,* 1 Environmental Applied Science and Management-Yeates School of Graduate Studies, Ryerson University, Toronto, ON M5B 2K3, Canada; [email protected] 2 Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Ryerson University, Toronto, ON M5B 2K3, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 May 2020; Accepted: 9 August 2020; Published: 11 August 2020 Abstract: This study examines land use change and impacts on urban and rural activity in Lagos State, Nigeria. To achieve this, multi-temporal land use and land cover (LULC) datasets derived from the GlobeLand30 product of years 2000 and 2010 for urban and rural areas of Lagos State were imported into ArcMap 10.6 and converted to raster files (raster thematic maps) for spatial analysis in the FRAGSTATS situated in the Patch Analyst. Thus, different landscape metrics were computed to generate statistical results. The results have shown that fragmentation of cultivated lands increased in the rural areas but decreased in the urban areas. Also, the findings display that land-use change resulted in incremental fragmentation of forest in the urban areas, and reduction in the rural areas. The fragmentation measure of diversity increased in the urban areas, while it decreased in the rural areas during the period of study. These results suggest that cultivated land fragmentation is a complex process connected with socio-economic trends at regional and local levels. In addition, this study has shown that landscape metrics can be used to understand the spatial pattern of LULC change in an urban-rural context. -

Economic Development in Urban Nigeria

RESEARCH REPORT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN URBAN NIGERIA JULY 2015 ROBIN BLOCH NAJI MAKAREM ICF International Univeristy College London MOHAMMED-BELLO YUNUSA NIKOLAOS PAPACHRISTODOULOU Ahmadu Bello University ICF International MATTHEW CRIGHTON ICF International i Rights and Permissions Except expressly otherwise noted or attributed to a third party, this report is © 2014 ICF International, under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial- ShareAlike CC BY-NC-SA. Please cite as follows: Bloch R., Makarem N., Yunusa M., Papachristodoulou N., and Crighton, M. (2015) Economic Development in Urban Nigeria. Urbanisation Research Nigeria (URN) Research Report. London: ICF International. Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike CC BY-NC-SA. Comments or enquiries related to this report or its datasets, which are available on request, should be addressed to [email protected] Cover photo: Nikolaos Papachristodoulou. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................... ii ACRONYMS .......................................................................................... iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 4 NIGERIA’S ECONOMY TODAY ................................................................. 6 KEY MACROECONOMIC TRENDS ................................................................... 6 NATIONAL INDUSTRIAL COMPOSITION -

Perceptions, Attitudes and Practices on Achistosomiasis in Delta State, Nigeria

289 Tanzania Journal of Health Research Volume 12, Number 4, October 2010 Perceptions, Attitudes and Practices on Achistosomiasis in Delta State, Nigeria NKECHI G. ONYENEHO7*1, PAUL YINKORE2, JOHN EGWUAGE3 and EMMANUEL EMUKAH4 1Department of Sociology/Anthropology, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria 2Ministry of Health, Asaba, Delta State, Nigeria 3Carter Center, Edo/Delta, Benin City, Nigeria 4Carter Center, Jos, Nigeria, Nigeria Abstract: Urinary schistosomiasis, which is one of the commonest forms of the parasitic disease is a major debilitating disease characterized by blood in urine. The main objective of the study reported here was to assess the knowledge, attitude/perception and practices of the people in Oshimili South and Ndokwa Northeast Local Government Areas of Delta State in Nigeria. A cross-sectional study of 400 randomly selected persons aged ≥15 years was undertaken using a uniform set of structured interview schedule administered by trained field assistants. This was supported with some qualitative data collected from in-depth interview with community leaders and school teachers as well as focus group discussions with community members. One-third of the people interviewed were aware of the schistosomiasis. For a majority however, the perceived causes of the disease included witchcraft and sexual or body contact with infected persons. For some of the respondents, the disease is not serious since it does not harm or prevent the victim from eating. In many cases the disease was not treated because of the belief that there is no effective cure for it and that it reoccurs after treatment. But perhaps more importantly, the infection is not treated because it is considered a normal growing up process, which the infected person outgrows. -

(ISWG) Meeting Yola, Adamawa State, Nigeria. Agenda Items/Discussions Responsible/Time

Minutes of Inter-Sector Working Group (ISWG) Meeting Yola, Adamawa State, Nigeria. ISWG Lead Moseray Sesay +2347031718734 [email protected] ISWG Co- Lead Momsiri W. Gambo +2347060486940 [email protected] Date and Location 23 January 2019/OCHA/IOM Conference Room Attendance UNHCR, OCHA, IOM, UNFPA, UNOCHA, ADSEMA, UNICEF, WHO, UNOHCR Agenda Items/Discussions Responsible/Timeline/Action Points Opening and Introductions N/A OCHA welcomed the partners Review of the December 2018 action point WASH water point not functional at Daware camp UNICEF has responded to the water needs at Daware camp Filled latrine in Malkohi camp No accredited vendor in Adamawa state. The previous was in OCHA urged UNICEF to get local vendors from Adamawa to carry out conjunction with FMC. Ministry of environment was to sort it their projects. OCHA to follow up with NEMA to get approval to dig a latrine at out as they are supported by UNICEF Malkohi camp NEMA disapproved digging a new latrine Lack of wash facility in Chikamidere and Wuro yanka. UNICEF to trigger the IDPs to construct their latrines Partners do not have capacity to respond to WASH needs in Girei UNICEF only build latrines in formal camps hence unable to build latrine at informal settlements for IDPs HEALTH Cases of Gonorrhoea, Hepatitis B and Malaria in the camps WHO Funding wasn’t secured to respond to the cases in the OCHA to advocate funding to Adamawa state. IDP camps in relation to Gonorrhoea, Hepatitis etc. Issues was raised in Maiduguri and their response was that they are structural issues. Save one million lives is a world bank funded project which will New way of working is being adopted to Cather for the be used to solve the issues related to STIs in the state.