A Troubled Profession? Episcopal Clergy and Vocation at the Turn of the Millennium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Korean-American Methodists' Response to the UMC Debate Over

religions Article Loving My New Neighbor: The Korean-American Methodists’ Response to the UMC Debate over LGBTQ Individuals in Everyday Life Jeyoul Choi Department of Religion, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA; [email protected] Abstract: The recent nationwide debate of American Protestant churches over the ordination and consecration of LGBTQ clergymen and laypeople has been largely divisive and destructive. While a few studies have paid attention to individual efforts of congregations to negotiate the heated conflicts as their contribution to the denominational debate, no studies have recounted how post-1965 immigrants, often deemed as “ethnic enclaves apart from larger American society”, respond to this religious issue. Drawing on an ethnographic study of a first-generation Korean Methodist church in the Tampa Bay area, Florida, this article attempts to fill this gap in the literature. In brief, I argue that the Tampa Korean-American Methodists’ continual exposure to the Methodist Church’s larger denominational homosexuality debate and their personal relationships with gay and lesbian friends in everyday life together work to facilitate their gradual tolerance toward sexual minorities as a sign of their accommodation of individualistic and democratic values of American society. Keywords: homosexuality and LGBTQ people; United Methodist Church; post-1965 immigrants; Korean-American evangelicals Citation: Choi, Jeyoul. 2021. Loving My New Neighbor: The Korean-American Methodists’ Response to the UMC Debate over 1. Introduction LGBTQ Individuals in Everyday Life. The discourses of homosexuality and LGBTQ individuals in American Protestantism Religions 12: 561. https://doi.org/ are polarized by the research that enunciates each denomination’s theological stance 10.3390/rel12080561 and conflicts over the case studies of individual sexual minorities’ struggle within their congregations. -

Clergy Personnel Manual Archdiocese of Portland Preface to the 2014 Edition of the Clergy Personnel Manual

CLERGY PERSONNEL MANUAL ARCHDIOCESE OF PORTLAND PREFACE TO THE 2014 EDITION OF THE CLERGY PERSONNEL MANUAL On December 8, 1979 Archbishop Cornelius Power promulgated the Clergy Personnel Manual. This Manual was the product of extensive study and consultation by the Clergy Personnel Board and finally a vote of the entire presbyterate. Since the original promulgation of the Manual, some chapters have been revised. This edition prints all the chapters in a uniform format. The organization and position titles within the Pastoral Center have changed. This edition references positions of offices that coincide with our current Pastoral Center organization. This 2014 edition of the Clergy Personnel Manual reflects our current personnel policies and structure. Members of the Clergy Personnel Board: Rev. Todd Molinari, Most Rev. Alexander K. Sample, Most Rev. Peter Smith, Rev. Jeff Eirvin, Rev. James Coleman, Rev. Ronald Millican, Rev. Richard Thompson, Rev. Michael Vuky, Rev. Angelo Te. Vicar for Clergy: Rev. Todd Molinari Archbishop of the Archdiocese of Portland: Most Rev. Alexander K. Sample i PREFACE TO THE 1995 EDITION OF THE CLERGY PERSONNEL MANUAL On December 8, 1979, Archbishop Power promulgated the Clergy Personnel Manual. This Manual was the product of extensive study and consultation by the Clergy Personnel Board and finally a vote of the entire presbyterate. Since the original promulgation of the Clergy Personnel Manual, some chapters, like the one on area vicars, have been added; others, like the one on pastors, have been revised. This edition prints all the chapters in a uniform format and notes the date each chapter was promulgated or revised. -

When You Consider Ordination

WHEN YOU CONSIDER ORDINATION CONSERVATIVE CONGREGATIONAL CHRISTIAN CONFERENCE April 2017 CONTENTS Ff When Considering Ordination • What is the call to Christian Ministry? • Who Should be Ordained? • The Local Church’s Responsibility The Candidate for Ordination • Preparation of Ordination Paper • Recommended Resources for Theological Development The Examination by the Vicinage Council • Some Suggested Forms WHEN CONSIDERING ORDINATION TO CHRISTIAN MINISTRY Ff It is a great and awesome privilege to be ordained or to help someone prepare for ordination. This pamphlet has been designed with candidates for ordination and ordaining churches in mind to help them understand what is involved in the ordina- tion process. To candidates, God’s Word says, “If anyone sets his heart on being an overseer, he desires a noble task” (I Tim.3:1). Our prayer is that God would raise up and call many into His service who are scripturally qualified, Spirit-filled, and zealous for His name. To churches, God’s Word says, “Everything should be done in a fitting and orderly way” (I Cor. 14:40). When we follow this Biblical admonition, we are a model to the candidate, and we reflect the importance we place on ordination. According to By-law VI, Section 2 of our Constitution and By-laws, “A candidate for Ordination to the Christian Ministry and subsequent ministerial membership in this Conference will be expected to have a life which is bearing the fruit of the Spirit, and which is marked by deep spirituality and the best of ethical practices. The candidate may be disqualified by any habits or WHEN YOU CONSIDER ORDINATION practices in his life which do not glorify God in his body, which belongs to God, or which might cause any brother in Christ to stumble.” By-law IV, Section 2, states: “A ministerial standing in this Conference shall require: (1) A minimum academic attainment of a diploma from an accredited Bible institute or the equivalent in formal education or Christian service. -

Clergy List Kunnamkulam - Malabar Diocese

CLERGY LIST KUNNAMKULAM - MALABAR DIOCESE PHONE NUMBER / E-Mail Sl No NAME PARISH NEDUVALLOOR CENTRE 1 Rev. Mathew Samuel 04998 286805/286806/285698(R) Mar Thoma College Mar Thoma College of Special Education 9946197386 Badiaduka, Peradale (PO) Kadamana Congregation Kasaragod - 671 551 [email protected] 2 Rev Lijo J George 0490-2412422 Kelakom Immanuel Mar Thoma Church 9447703289 Kelakom P O, Kannur 670 674 [email protected] Neduvaloor Bethel 3 Rev. Binu John 0460-2260220 St.Thomas School Bethel Mar Thoma Church 9846619668 Neduvaloor, Chuzhali (PO), Kannur 670 361 [email protected] Kannur Immanuel 4 Rev Isac P Johnson 0497-2761150 Immanuel M T Church South Bazar P. O, 9990141115 Kannur - 670 002 [email protected] 5 Rev.Febin Mathew Prasad 04602-228328 Arabi Arohanam Arohanam Mar Thoma Church 9847836016 Kolithattu Hermon Arabi P O [email protected] Ulickal (Via), Kannur - 670 705 Cherupuzha Jerusalem, 6 Rev. Reji Easow 0497-2802250 Payannur Bethel Mar Thoma Divya Nikethan 7746973639 Vilayamcodu P O, Pilathara Kannur - 670 504 [email protected] 7 Rev. A. G. Mathew, Rev Rajesh R 04994-280252 (R), 284612 (O) Kasargod St.Thomas Mar Thoma School of Deaf 9447259068, 9746819278 , Parappa Ebenezer Cherkala, Chengala [email protected] Mar Thoma Deaf School Kasragod - 671 541 PHONE NUMBER / E-Mail Sl No NAME PARISH KOZHIKODE CENTRE 8 Rev. Biju K. George 0495 - 2766555 Kozhikode St. Pauls St. Pauls M. T. Church 9446211811 Y M C A Road, Calicut - 673 001 [email protected] 9 Rev. Robin T Mathew 0496 2669449 Chengaroth Immanuel Immanuel M. T. Parsonage 9495372524 Chengaroth P.O, Peruvannamoozhy Anakkulam Sehion Calicut - 673 528 [email protected] 10 Rev. -

Catholic Clergy There Are Many Roles Within the Catholic Church for Both Ordained and Non-Ordained People

Catholic Clergy There are many roles within the Catholic Church for both ordained and non-ordained people. A non-ordained person is typically referred to as a lay person, or one who is not a member of the clergy. One who is ordained is someone who has received the sacrament of Holy Orders. In the Catholic Church only men may be ordained to the Clergy, which sets us apart from other Christian denominations. The reasoning behind this is fairly straightforward; Since God himself, in His human form of Jesus Christ, instituted the priesthood by the formation of the 12 Apostles which were all male, The Church is bound to follow His example. Once a man is ordained, he is not allowed to marry, he is asked to live a life of celibacy. However married men may become ordained Deacons, but if their wife passes away they do not remarry. It’s very rare, but there are instances of married men being ordained as priests within the Catholic Church. Most are converts from other Christian denominations where they served in Clerical roles, look up the story of Father Joshua Whitfield of Dallas Texas. At the top of the Catholic Clergy hierarchy is the Pope, also known as the Vicar of Christ, and the Bishop Rome. St. Peter was our very first Pope, Jesus laid his hands upon Peter and proclaimed “upon this rock I will build my church, and the gates of the netherworld shall not prevail against it.” ~MT 16:18. Our current Pope is Pope Francis, formally Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Argentina. -

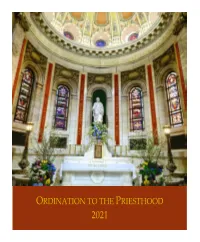

ORDINATION 2021.Pdf

WELCOME TO THE CATHEDRAL OF SAINT PAUL Restrooms are located near the Chapel of Saint Joseph, and on the Lower Level, which is acces- sible via the stairs and elevator at either end of the Narthex. The Mother Church for the 800,000 Roman Catholics of the Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, the Cathedral of Saint Paul is an active parish family of nearly 1,000 households and was designated as a National Shrine in 2009. For more information about the Cathedral, visit the website at www.cathedralsaintpaul.org ARCHDIOCESE OF SAINT PAUL AND MINNEAPOLIS SAINT PAUL, MINNESOTA Cover photo by Greg Povolny: Chapel of Saint Joseph, Cathedral of Saint Paul 2 Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis Ordination to the Priesthood of Our Lord Jesus Christ E Joseph Timothy Barron, PES James Andrew Bernard William Duane Duffert Brian Kenneth Fischer David Leo Hottinger, PES Michael Fredrik Reinhardt Josh Jacob Salonek S May 29, 2021 ten o’clock We invite your prayerful silence in preparation for Mass. ORGAN PRELUDE Dr. Christopher Ganza, organ Vêpres du commun des fêtes de la Sainte Vierge, op. 18 Marcel Dupré Ave Maris Stella I. Sumens illud Ave Gabrielis ore op. 18, No. 6 II. Monstra te esse matrem: sumat per te preces op. 18, No. 7 III. Vitam praesta puram, iter para tutum: op. 18, No. 8 IV. Amen op. 18, No. 9 3 HOLY MASS Most Rev. Bernard A. Hebda, Celebrant THE INTRODUCTORY RITES INTROITS Sung as needed ALL PLEASE STAND Priests of God, Bless the Lord Peter Latona Winner, Rite of Ordination Propers Composition Competition, sponsored by the Conference of Roman Catholic Cathedral Musicians (2016) ANTIPHON Cantor, then Assembly; thereafter, Assembly Verses Daniel 3:57-74, 87 1. -

Three-Warnings-Of-Jesus-To-Clergy

Rev. Kyewoon Choi, ManahawkinMethodist.org, Manahawkin, NJ 08050 August 1, 2021 Three Warnings of Jesus to Clergy Mark 12:38-40 (New American Standard Bible) 38 And in His teaching He was saying: “Beware of the scribes who like to walk around in long robes, and like personal greetings in the marketplaces, 39 and seats of honor in the synagogues, and places of honor at banquets, 40 who devour widows’ houses, and for appearance’s sake offer long prayers. These will receive all the more condemnation.” Introduction Disclaimer: this morning’s message is mainly for me, a pastor and member of clergy. In view of God’s mercy, I pray that all clergy take Jesus’ warnings to them as seriously as I do. Thirty some years ago, as I entered parish ministry, a wise counsel advised me to beware of three ministry killers, a.k.a. three “S”s. Silver, Sex, and Sloth. Since then, I am very mindful of such dangers in ministry. In today’s text, Jesus also warns clergy to beware of three things: the desire of recognition, the love of money, and hypocrisy. Content When you read the Bible, sometimes you feel that the words are jumping out of the page and directly speaking to you. That’s how I felt one day as I was reading today’s text. I felt Jesus was directly speaking to me, warning me of three dangers lurking in the path to faithful ministry. Beware, He commanded me, of the three sins that I as pastor can easily commit without knowing. -

The Abrahamic Faiths

8: Historical Background: the Abrahamic Faiths Author: Susan Douglass Overview: This lesson provides background on three Abrahamic faiths, or the world religions called Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. It is a brief primer on their geographic and spiritual origins, the basic beliefs, scriptures, and practices of each faith. It describes the calendars and major celebrations in each tradition. Aspects of the moral and ethical beliefs and the family and social values of the faiths are discussed. Comparison and contrast among the three Abrahamic faiths help to explain what enabled their adherents to share in cultural, economic, and social life, and what aspects of the faiths might result in disharmony among their adherents. Levels: Middle grades 6-8, high school and general audiences Objectives: Students will: Define “Abrahamic faith” and identify which world religions belong to this group. Briefly describe the basic elements of the origins, beliefs, leaders, scriptures and practices of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Compare and contrast the basic elements of the three faiths. Explain some sources of harmony and friction among the adherents of the Abrahamic faiths based on their beliefs. Time: One class period, or outside class assignment of 1 hour, and ca. 30 minutes class discussion. Materials: Student Reading “The Abrahamic Faiths”; graphic comparison/contrast handout, overhead projector film & marker, or whiteboard. Procedure: 1. Copy and distribute the student reading, as an in-class or homework assignment. Ask the students to take notes on each of the three faith groups described in the reading, including information about their origins, beliefs, leaders, practices and social aspects. They may create a graphic organizer by folding a lined sheet of paper lengthwise into thirds and using these notes to complete the assessment activity. -

Engagement Guidelines: Orthodox Christian Leaders

Tip Sheets: Engaging Faith Communities V1.2 Engagement Guidelines: Orthodox Christian Leaders Religion Called: Orthodox Christianity Adherents Consider Themselves: Christian and are called Orthodox Christians House of Worship: Church or Cathedral First Point of Contact: Senior parish priest a.k.a. pastor Religious Leader: Priest or Deacon Spoken Direct Address: Use “Father” Physical Interaction: Handshake O.K. across sexes HOUSE OF WORSHIP Churches are local houses of worship. A parish refers to the congregation of a particular church. Parishes often have non-sacred spaces such as multipurpose rooms, schools, gyms, or offices. Cathedrals are large centers of worship for an entire regional area run by a Diocese or Archdiocese. Monasteries and convents house monks and nuns (respectively), and may include a chapel and areas for instruction/work. RELIGIOUS LEADERS Ordained/Commissioned/Licensed Leaders Orthodox Christian leadership is hierarchical with each national/ethnic branch having its own structure and leadership. Regional leadership generally falls to bishops (or archbishops, catholicos, or metropolitans). Priests and deacons provide sacramental and spiritual leadership; priests often are in charge of a local parish. Both priests and deacons are permitted to marry. Holy Orders and Lay Leaders Monks and nuns are non-ordained (lay) leaders (except for hiermonks who are ordained priests or deacons) who have usually taken a vow of poverty, celibacy, and obedience and often live an active vocation of both prayer and service. Many monks, nuns, and laypersons have important leadership positions —avoid assumptions based on title. Some U.S. parishes have lay administrators who take on many of the roles once the exclusive domain of clergy. -

Priesthood Ordination

Priesthood Ordination The most humbling task of a bishop, and at the same time a great joy and privilege, is to ordain a priest for service to the Church. It is humbling because it is a moment when the power of Jesus uses a weak human instrument to continue what Jesus did on the night before the died, insuring that his great sacrifice, offered once for all on the Cross on Good Friday, would continue to be with his people. So many of you here have helped bring these deacons to the altar of ordination today. To parents and other family members, to priests, teachers, seminary professors and schoolmates, to friends and associates, I express the thanks of the Archdiocese for your special role. Later, I shall speak in greater detail. Also, I want to call attention to a step that makes today’s Ordination Mass more like other Masses: there will be a collection, and the ordination class has determined that the collection will be divided into three parts, one-third for the education of future priests, one-third for our inner city schools, and one-third for the needs of the Cathedral Church we are privileged to use today. Those to be ordained today have chosen the readings from the word of God that give a color, a flavor, a sense of what is to happen here in the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen. The Church as well, through the extraordinary ministry of Pope John Paul H, to whom the deacons referred in their presentation to me, has made a contribution. -

Clergy Notes Offers a Glimpse of the Role Clergy Can Play in Teaching About Religion

VOLUME FOUR ISSUE ELEVEN JULY 2000 COLLEAGUES: Last month the Supreme Court ruled that student-led prayer at a Texas high school football game represented an unconstitutional establishment of religion. Is there any place left in the schools for religion? When I was serving as a university chaplain, an English department colleague told me, “If the chaplain was doing a better job, I wouldn’t have to work so hard.” He wasn’t weary of offering crisis counseling to students, or of preaching honesty at exam time. Instead, he bemoaned the fact that only a minority of his students knew the source or meaning of references to an exodus, to Goliath, or to 30 pieces of silver. The Supreme Court has never forbidden teaching about religion’s role in history and culture. This issue of Clergy Notes offers a glimpse of the role clergy can play in teaching about religion. You may be a key resource for a teacher who wants her students to learn about scriptural allusions in literature, or how religion has shaped art and music. Are you an authority in world religions? Clergy have been invited into the classroom to discuss religious stereotyping, territorial conflicts rooted in religion, and the meaning of religious holidays. Have you participated in historic events such as the civil rights movement? Can you discuss the role played by your particular tradition in formulating laws, or in founding public institutions? Football games may not have a prayer, but students still can learn about religion’s role on the larger playing field of American culture. -

Magisterial Reformers and Ordination P

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Faculty Publications Church History 1-2013 Magisterial Reformers and Ordination P. Gerard Damsteegt Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/church-history-pubs Part of the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Damsteegt, P. Gerard, "Magisterial Reformers and Ordination" (2013). Faculty Publications. Paper 55. http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/church-history-pubs/55 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Church History at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MAGISTERIAL REFORMERS AND ORDINATION By P. Gerard Damsteegt Seventh-day Adventists Theological Seminary, Andrews University 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. LUTHER AND ORDINATION ............................ Error! Bookmark not defined. Luther’s ordination views as a Roman Catholic priest ..................................... 3 Luther's break from sacramental view of ordination ........................................ 4 Equality of all believers and the function of priests and bishops ..................... 5 Biblical Ordination for Luther .......................................................................... 6 Implementing the biblical model of ordination ......................................... 8 Qualifications for ordination