Path of Least Resistence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slave Housing Data Base

Slave Housing Data Base Building Name: Howard’s Neck, Quarter B Evidence Type: Extant Historical Site Name: Howard's Neck City or Vicinity: Pemberton (near Cartersville, and Goochland C.H.) County: Goochland State: Virginia Investigators: Douglas W. Sanford; Dennis J. Pogue Institutions: Center for Historic Preservation, UMW; Mount Vernon Ladies' Association Project Start: 8/7/08 Project End: 8/7/08 Summary Description: Howards’ Neck Quarter B is a one-story, log duplex with a central chimney and side-gable roof, supported by brick piers, and is the second (or middle) of three surviving currently unoccupied quarters arranged in an east-west line positioned on a moderately western sloping ridge. The quarters are located several hundred yards southwest of the main house complex. The core of the structure consists of a hewn log crib, joined at the corners with v-notches, with a framed roof (replaced), and a modern porch on the front and shed addition to the rear. Wooden siding currently covers the exterior walls, but the log rear wall enclosed by the shed is exposed; it is whitewashed. The original log core measures 31 ft. 9 in. (E-W) x 16 ft. 4 in. (N-S); the 20th-century rear addition is 11 ft. 8 in. wide (N-S) x 31 ft. 9 in. long (E-W). A doorway allows direct access between the two main rooms, which may be an original feature; a doorway connecting the log core with the rear shed has been cut by enlarging an original window opening in Room 1. As originally constructed, the structure consisted of two first-floor rooms, with exterior doorways in the south facade and single windows opposite the doorways in the rear wall. -

U.S. EPA, Pesticide Product Label, ARCH OIT 45, 01/15/2009

c (' UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY ro WASHINGTON, D.C. · 20460 JAN 1 5 2009 &EPA'~;;:IPttiectioo Office of Pesticide Programs Arch Chemical, Inc. 1955 Lake Park Drive, Suite 100 Smyrna, GA 30080 . Attention: Garret B. Schifilliti Senior Regulatory Manager Subject: Arch OIT 45 EPA Registration No. 1258-1323 Your Amendment Dated December 16,2008 This will acknowledge receipt of your notification of changes to the Storage and Disposal Statements for the "Container Rule", submitted under the provisions of FIFRA Section 3(c)(9). Based on a review of the submitted material, the following comments apply. The Notification dated December 18, 2008 is in compliance with PR Notice 98-10 and is acceptable. This Notification has been added to your file. If you have any questions concerning this letter, please contact Martha Terry at (703) 308-6217. Sincerely ~h1'b Marshall Swindell ~ Product Manager (33) Regulatory Management Branch 1 Antimcrobials Division (7510C) ( ( Forrt., _oroved. O. _No. 2070-0060 . emir.. 2·28·95 United States Registration OPP Identifier Number &EPA Environmental Protection Agency Amendment Washington, DC 20460 @.;. Other· Application for Pesticide - Section I 1. Company/Product Number 2. EPA Product Manager 3. Proposed Classification 1258-1323 Marshall Swindell [2] None D Restricted 4. Company/Product (Name) PM' Arch OIT 45 5. Nama and Address of Applicant (Include ZIP Code) 6. Expedited Reveiw. In accordance with FIFAA Section 3(c)(3) Arch Chemicals, Inc. (b)(il. my product is similar or identical in composition and labeling to: 1955 Lake Park Drive EPA Reg. No. ________________________________ Smyrna, GA 30080 D Check if this is a neW address Product Name Section - II Amendment - Explain below. -

California Licensed Contractor ©

WINTER/SPRING 2011 California © Licensed Contractor Stephen P. Sands, Registrar | Edmund G. Brown Jr., Governor 2011 Contracting Laws That Affect You CSLB Has an Licenses for Limited Liability Companies (LLCs) Coming App for That The passage of Senate Bill 392 (and various provisions of the Contractors State License Law CSLB recently including B&P Code Sections 7071.65 and 7071.19) authorizes CSLB to issue contractor launched its new licenses to limited liability companies (LLCs). The law says that CSLB shall begin processing “CSLB mobile” LLC applications no later than January 1, 2012. The LLC will be required to maintain website: www.cslb. liability insurance of between $1,000,000 and $5,000,000, and post a $100,000 surety ca.gov/mobile. bond in addition to the $12,500 bond already required of all licensees. (Senate Bill 392 is CSLB mobile now available at: www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/09-10/bill/sen/sb_0351-0400/sb_392_bill_20100930_ enables users to chaptered.pdf.) check a license, get CSLB office locations, However, do not apply for an LLC license yet; CSLB is not issuing licenses to LLCs at this time. sign up for e-mail alerts, and help report unlicensed activity right from their “smart” CSLB staff is developing new application procedures, creating applications, and putting in phone. place important technology programming changes that are necessary for this new feature. CSLB anticipates that it will be able to accept and process LLC applications late in 2011. “This is an exciting new step for CSLB,” said Registrar Steve Sands. “This application The best way to receive future updates is to sign up for CSLB E-Mail Alerts at www.cslb.ca.gov. -

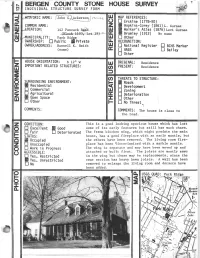

ACCESSIBLE:^^ Byes, Unrestricted

ACCESSIBLE:^^ BYes, Unrestricted CONSTRUCTION DATE/SOURCE: NUMBER OF STORIES: 1-1/2 c. 1770-1810/Architectural evidence CELLAR: B Yes —43 No DC BUILDER: An Ackerson, probably John. CHIMNEY FOUNDATION: O D Stone Arch V) FORM/PLAN TYPE: • Brick Arch, Stone Foundation 111 "F", 5 bay, center hall, 2 rooms deep D Other (32 f 6" x 43'8"). Frame addition Q added as kitchen. FLOOR JOISTS: 6-7" x 9" deep, 23-24" between, 1235-13" floorboards. FRAMING SYSTEM: FIRST FLOOR CEILING HEIGHT: 8'4" ~ In ermed late Bearing Wall FIRST FLOOR WALL THICKNESS: Clear Span 24" L Other GARRET FLOOR JOISTS: Not visible. EXTERIOR MALL FABRIC: GARRET: Well cut red sandstone all around, Unfinished Space except some rubble on west end. B Finished Space ROOF: FENESTRATION: Gable (wing) Not original. 32" x 58" in front, • Gambrel trapezoidal lintels. D Curb D Other ENTRANCE LOCATION/TYPE: EAVE TREATMENT: Plain entrance door in center 37" x 7*5", Sweeping Overhang not original. Supported Overhang (in front) No Overhang D Boxed Gutter D Other This house Is significant for its architecture and its association with the exploration and settlement of the Bergen County, New Jersey area. It is a reasonably well preserved example of the Form/Plan Type as shown and more fully described herein. As such, it is included in the Thematic Nomination to the National Register of Historic Places for the Early Stone Houses of Bergen County, New Jersey. FLOOR PLANS Howard I. Durie believes this house to have been built about 1775 for John G. Eckerson, son of Garret Eckerson, on land Garret and his 0s! cousin Garret Haring purchased on May 4, 1759 from Rev. -

Living Wage Report Urban Vietnam

Living Wage Report Urban Vietnam Ho Chi Minh City With focus on the Garment Industry March 2016 By: Research Center for Employment Relations (ERC) A spontaneous market for workers outside a garment factory in Ho Chi Minh City. Photo courtesy of ERC Series 1, Report 10 June 2017 Prepared for: The Global Living Wage Coalition Under the Aegis of Fairtrade International, Forest Stewardship Council, GoodWeave International, Rainforest Alliance, Social Accountability International, Sustainable Agriculture Network, and UTZ, in partnership with the ISEAL Alliance and Richard Anker and Martha Anker Living Wage Report for Urban Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam with focus on garment industry SECTION I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 3 1. Background ........................................................................................................................... 4 2. Living wage estimate ............................................................................................................ 5 3. Context ................................................................................................................................. 6 3.1 Ho Chi Minh City .......................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Vietnam’s garment industry ........................................................................................ 9 4. Concept and definition of a living wage ........................................................................... -

Download the Resource Guide

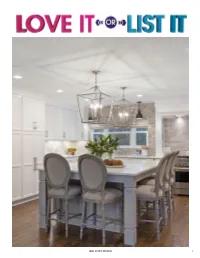

BIG COAT MEDIA 1 MICHAEL + BECKY Michael and Becky loved their sizeable lot and house when they first purchased it six years ago. Unfortunately, the finishes inside the house are artifacts of the 1970’s and their plans to update it have taken a back seat to their busy family life. Michael loves their large family room and bar, but Becky feels the entire floor plan is too cut off for entertaining, and simply dated and dysfunctional. She wants an open concept, updated house for her family and guests, but is determined to find a different house that better suits their needs. Michael is not ready to give up on their huge lot and great neighborhood, and hopes Hilary’s ex- pert designs can bring this time capsule of a house into the 21st century. Becky knows David will find them a house that Michael will love entertaining in for decades to come. BIG COAT MEDIA 2 KITCHEN General Contractor: Kusan Construction Lighting: Generation Lighting - Parker Place Mini Pendants | Savoy House - Townsend Pendants Counter Stools: Aidan Gray - Grace Counter Stools Cabinetry: 1st Choice Cabinetry - Perimeter: Bentley Maple White, Island: Bentley Maple Grit, Recessed Cabinetry: Bentley, Maple Grit | SMJ Cabinetry, LLC. Cabinetry Hardware: Schaub - Heathrow Round Knobs and Pulls Custom Roman Shade: Noble Design Home Studio Tile: Mosaic Home Interiors - Wooden White Honed Premium Marble Quartz: Absolute Stone Corporation - Pure Surfaces Calacatta Oro Quartz Appliances: Garner Appliance & Mattress Plumbing Fixtures: Vault Undermount Sinks, Simplice Faucet, HiRise -

EDWARD MOONEY HOUSE (18 BOWERY BUILDING) 1 Borough of Manhattan

~ndmarks Preservation Commission August 23, 19661 Number 1 LP-D084 EDWARD MOONEY HOUSE (18 BOWERY BUILDING) 1 Borough of Manhattan. Built between 1785 and 1789; architect unknown. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 162, Lot 53. On October 19, 1965, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Edward Mooney House (the 18 Bowery Building) and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site. (Item No, 56). The hearing had been du~ advertised in accordance ~th the provisions of Law. Two witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS This is the· only know town house surviving in Manhattan which dates from the period of the American Revolution. It was built between 1785 - a scant two years after the British evacuation of the City- and 1789, the year George Washington was inaugurated as first President of the United States and New York City became the first Capital of the nation. The house stands on its original site, at the southeast corner of Pell Street and the Bower,y, and its red brick facade above the street-floor level is in a remarkably good state of preservation, A brick extension, equalling the size of the original structure,. was added in l80J. l The architectural style of the house is EarlY Federal, reflecting strongly its Georgian antecedents in construction, proportions and design details. It is three stories in height, with s finished-garret beneath a gambrel roof, Two features of special note which verif,y the documented age of the building are the hand-hewn timbers framing the roof and the broad width of the front windows in proportion to their height. -

A K Young Assoc Po Box 201265 Austin, Tx 78720-1265 Aan Garret-Coleman & Associates Inc 9890 Silver Mountain Dr Austin, T

A K Young Assoc Aan Garret-Coleman & Associates Inc Accessology Too Llc Po Box 201265 9890 Silver Mountain Dr 301 W. Louisiana St. Austin, Tx 78720-1265 Austin, Tx 78737 Mckinney, Tx 75069 Adisa Public Relations Aguirre & Fields Lp Alan Y Taniguchi Architect & Assoc Inc 506 W 12th Street 12708 Riata Vista Circle Ste A-109 1609 W 6th St Austin, Tx 78701 Austin, Tx 78727 Austin, Tx 78703-5059 Alliance-Texas Engineering Company Altura Solutions L P Ana D Gallo 11500 Metric Blvd Bldg M1, Ste 150 4111 Medical Parkway, Suite 301 1501 Barton Springs Rd #230 Austin, Tx 78758 Austin, Tx 78756 Austin, Tx 78704 Andrew A Rodriguez Apex Cost Consultants Inc Appliedtech Group L L C 8137 Osborne Dr 707 West Vickory Blvd Suite 102a 12059 Lincolnshire Dr Austin, Tx 78729-8074 Fort Worth, Tx 76104 Austin, Tx 78758-2217 Aptus Engineering Llc Ark Engineer And Consultants, Inc. Armor Affiliates Inc 1919 S 1st Street Building B 2214 Whirlaway Drive 4257 Gattis School Rd Austin, Tx 78704 Stafford, Tx 77477 Round Rock, Tx 78664 Asakura Robinson Company L L C Asd Consultants Inc Austin Architecture Plus Inc 816 Congress Avenue, Suite 1270 8120 N Ih 35 1907 N Lamar Blvd Ste 260 Austin, Tx 78701 Austin, Tx 78753 Austin, Tx 78705-4900 Aviation Alliance Inc Axiom Engineers Inc Ays Engineering, Llc Po Box 799 13276 Research Blvd Ste 208 203 E. Main Street Ste 204 Colleyville, Tx 76034-0799 Austin, Tx 78750 Round Rock, Tx 78664 Amaterra Environmental, Inc. Amanda H Tulos Azcarate & Associates Consulting Engineers, Llc 4009 Banister Lane, Ste. -

Town of Marbletown Historic Preservation Commission MARBLETOWN LANDMARK DESIGNATION APPLICATION

Town of Marbletown Historic Preservation Commission MARBLETOWN LANDMARK DESIGNATION APPLICATION This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10- 900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Bevier Stone House other names/site number Van Leuven-Bevier Stone House 2. Location street & number 2682 NY Route 209 not for publication city or town Marbletown vicinity state New York code NY county Ulster code 111 zip code 12401 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Signature of certifying official/Title Date State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. Signature of commenting official Date Title State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government 4. -

Garret Cottage, Whiting Bay

Garret Cottage, Whiting Bay Invercloy House, Brodick, Isle of Arran KA27 8AJ 01770 302310 | [email protected] www.arranestateagents.co.uk GARRET COTTAGE, WHITING BAY, KA27 8PZ IN BRIEF • Charming detached cottage • Desirable village location • Walk-in condition • Off-road parking • Unrestricted sea views • Ideal retiral or starter home DESCRIPTION Garret Cottage is a detached cottage villa which has been lovingly renovated to create a spacious, light and bright home. It enjoys the ideal village location, close to all the amenities of Whiting Bay and enjoys stunning sea views across to the Ayrshire coast. Accommodation comprises entrance porch, fitted kitchen with breakfasting area, double bedroom with built in wardrobe, bathroom and a large storage cupboard. On the upper floor there is a spacious lounge with dining area, enjoying plenty of light from the front facing triple aspect dormer window and two roof windows. DIRECTIONS From Brodick Pier turn left and proceed south through Lamlash to Whiting Bay. On entering the village, pass the Sandbraes playing field on the left, Garret Cottage is the first property on the right, immediately after the Bay Stores. GARDEN Access from the road is by means of a gravel driveway that leads up to the property, where there is ample space for parking and turning. At the front the cottage there is a paviour walk way and a patio area for alfresco dining - the perfect spot for enjoying a morning coffee and the peaceful seaside views. To the rear, a few steps lead to the securely fenced terraced lawn area with a small paviour patio area and drying green. -

1 Before the District Council for Montgomery County

BEFORE THE DISTRICT COUNCIL FOR MONTGOMERY COUNTY, MARYLAND IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATION * OF EYA DEVELOPMENT LLC AND * BL STRATHMORE LLC * FOR REZONING TO THE * Zoning Application No. H-______ CRNF 0.75, C 0.25, R 0.75, H 50 * ZONE CLASSIFICATION * STATEMENT OF JUSTIFICATION The Applicants, EYA Development LLC (“EYA”) and BL Strathmore LLC (“Brandywine”) (collectively, the “Applicants”), by and through their attorneys, Miles & Stockbridge, P.C., are applying for a local map amendment requesting the rezoning of a portion of the property located at 4920 Strathmore Avenue, more particularly known as Parcel No. N045, Parcel B, Garrett Park Academy of the Holy Cross, as shown on Plat No. 208241, and all of the property located at 4910 Strathmore Avenue, more particularly known as Parcel N875, Parcel A, Garret Park- Holy Cross Convent, as shown on Plat No. 9347 (collectively, the “Property”), to the CRNF 0.75, C 0.25, R 0.75, H 50 (Commercial Residential Neighborhood- Floating) zoning classification (the “Application”). The Application seeks to allow for the future redevelopment of the Property, which is located within approximately ½ mile of both the Grosvenor Metro Station and the Garrett Park Marc Station, with up to 125 single family dwelling units and a 145 bed residential care facility (the “Project”). As discussed more fully below, the Application complies with all applicable review requirements and criteria necessary for approval. I. Background The Property consists of a total of approximately 15.36 acres and is currently improved with the vacant St. Angela Hall retirement home and open space/ surplus frontage associated with the Academy of the Holy Cross. -

406 11Th Ave SE Staff Report

CPED STAFF REPORT Prepared for the Heritage Preservation Commission HPC Agenda Item #09 April 7, 2020 PLAN10470 HERITAGE PRESERVATION APPLICATION SUMMARY Property Location: 406 11th Avenue SE Project Name: 406 11th Avenue SE Demolition Prepared By: Rob Skalecki, City Planner, (612) 673-5179 Applicant: Garret Duncan, NorthBay Companies Project Contact: Garret Duncan Ward: 3 Neighborhood: Marcy-Holmes Neighborhood Request: To demolish the existing building at 406 11th Avenue SE. Required Applications: Demolition of Historic To demolish the existing building at 406 11th Ave SE. Resource HISTORIC PROPERTY INFORMATION Current Name House Historic Name House Historic Address 406 11th Avenue SE Original Construction 1901 Date Original Architect William Kenyon Original Builder Edward James Davis Original Owner Mary Lochren Historic Use Single-Family Dwelling Current Use Multiple-Family Dwelling Date Application Deemed Complete February 3, 2020 Date Extension Letter Sent February 25, 2020 End of 60-Day Decision Period April 3, 2020 End of 120-Day Decision Period June 2, 2020 Department of Community Planning and Economic Development PLAN10470 SUMMARY BACKGROUND. The property contains a two-and-one half story Queen Anne style home constructed in 1901. The property was designed by William Kenyon and built by Edward James Davis for Mary Lochren. Ms. Lochren lived near these properties with her husband and purchased several lots on this corner for development by William Kenyon and Edward Davis. She was the only person listed on the deed and as the owner on the building permits and appears to have built the homes for investment purposes as single-family dwellings. However due to the homes size and location, they quickly became multiple-family residences and attracted Sorority and Fraternity groups.