Determinants of SARS-Cov-2 Infection in Italian Healthcare Workers: a Multicenter Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postgraduate Courses Undergraduate and Five Schools: Mathematical, Physical and Graduate Levels

unige.it STUDENT FACULTY ENROLLMENT More than 1,300 More than 30,000 faculty members students at both distribuited over Postgraduate courses undergraduate and five schools: Mathematical, Physical and graduate levels. Natural Sciences 2018/2019 Medical and Pharmaceutical Sciences Polytechnic Social Sciences Humanities Università di Genova The University of Genoa (UNIGE) is vides a truly multi-disciplinary international companies (e.g. IIT). Via Balbi 5 - 16126 Genova one of the most ancient of the Euro- teaching offer. • UNESCO Chair “Anthropology of pean large universities; with about 280 • The “Scuola superiore dell’Università Health. Biosphere and Healing Sys- +39 010 20991 educational paths distributed in the degli Studi di Genova (IANUA)” tems” established in 2014 headquarters in Genoa and the learn- encourages advanced educational LIBRARIES unige.it ing centres of Imperia, Savona and La paths of didactic and scientific ex- The University Library and the City Spezia, it comes up to the community cellences for worthy students se- Library System of Genoa have merged as a well-established reality through- lected by public contest. their services to create a single Inte- out the region. grated Library System. The broad ar- Located at the heart of a superb city, RESEARCH ray of services offered by the Univer- offering splendors of its medieval and sity Library includes both traditional @unigenova baroque heritage and site of the largest • Worldwide experts in all domains involving the sea: its habitat, its text consultation and innovative, high and most productive harbour in Eu- tech services. rope, the University of Genoa is one of economy, its exploitation. the most renowned multidisciplinary public universities in Italy, with peaks • Tight connections with one of the CAMPUS of excellence in several scientific and biggest oncological research hospi- • The oldest Campus, site of the Social technological domains. -

Curriculum Vitae

C URRICULUM V ITAE - A NNA D E G RASSI PERSONAL INFORMATION Surname Name De Grassi Anna Date of birth 03-02-1976 Department Bioscienze, Biotecnologie e Biofarmaceutica Institution Università degli Studi di Bari “Aldo Moro” Street Address Via Orabona 4, 70125 Bari - Italy. Phone/Fax +39 080 5443614/ +39 080 5442770 E-mail address [email protected] Researcher Orcid Identifier https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7273-4263 EDUCATION 2007 PhD in Genetics and Molecular Evolution, University of Bari – Italy 2004 Master Diploma in Bioinformatics, University of Turin – Italy, 110/110 2003 Qualification to practice the profession of Biologist 2002 University Diploma in Biological Sciences, University of Bari – Italy, 110/110 cum laude 1994 Secondary School Diploma, Liceo Classico Q. Orazio Flacco, Bari – Italy, 60/60 RESEARCH ACTIVITY IN ITALY From October 2012 Assistant Professor (BIO/13), Department of Biosciences, Biotechnology and Biopharmaceutics, University of Bari, Computational Genomics applied to Cancer and Rare Diseases 2007-2011 Post-Doc and Staff Scientist, Department of Experimental Oncology, European Institute of Oncology, Milan, Deep-Sequencing and Evolution of Cancer Genomes 2004-2007 PhD student, CNR – Institute of Biomedical Technologies (ITB), Bari, Comparative Genomics of gene families in vertebrates and Microarray Analysis of Human Cancer Cell Models 2003-2004 Master Diploma Student, Department of Clinical and Biological Sciences, University of Turin, Detection and Analysis of Genes Involved in Breast Tumor Progression in the her/neut Mouse Model Using Expression Microarrays 2003 Graduate Student, Cavalieri Ottolenghi Foundation, Turin, Actin-Tubulin Interaction in D. melanogaster Embryonic Cell Lines 2001-2002 Undergraduate Student, Department of Genetics, University of Bari, Evolution of Stellate-like and Crystal-like Sequences in the Genus Drosophila RESEARCH ACTIVITY ABROAD Dec. -

ASPO 2018 – Roosevelt Hotel, New York, NY

ASPO 2018 – Roosevelt Hotel, New York, NY SATURDAY, MARCH 10, 2018 Noon – 3:00pm Mock Study Section (limited to 20 participants) Cancer Prevention & Control Associate Directors/Program Leaders Meeting - 3:00pm – 7:00pm Part 1 (Invitation only) Organizer: Electra Paskett, PhD, Ohio State University SUNDAY, MARCH 11, 2018 8:00am – 5:00pm Registration Cancer Prevention & Control Associate Directors/Program Leaders Meeting - 8:00am – Noon Part 2 (Invitation only) Organizer: Electra Paskett, PhD, Ohio State University 9:00am – Noon New Investigators Workshop (Invited Applicants Only) Organizer: Judith Jacobson, DrPH, MPH, Columbia University 12:30pm – 3:30pm Working Lunch Meeting of the ASPO Executive Committee (invitation only) 1:00pm – 3:45pm ASPO Junior Members Sessions Session 1: Negotiation: Strategies and Best Practices Co-Chairs: Alexandra White, PhD, National Inst of Environmental Health Alicia Best, PhD, University of South Florida Session 2: Industry vs. Academia: Making a Decision for the Next Step in Your Career Co-chairs: Adriana Coletta, PhD, UT MD Anderson Cancer Center, and Heather Leach, PhD, Colorado State University 3:00pm – 3:45pm Meeting of NCI R25T& T32 Training Program Principal Investigators Organizer: Shine Chang, PhD, UT M.D. Anderson Cancer Center 4:00pm – 4:30pm Opening Session of the ASPO General Meeting ASPO Welcome President: Peter Kanetsky, PhD, MPH, Moffitt Cancer Center 4:30pm – 5:00pm Cullen Tobacco Address Thomas H. Brandon, PhD, Director, Tobacco Reesearch & Intervention Program, Moffitt Cancer Center Tobacco -

Laboratorio Di Ontologia

UNIVERSITÀ LABORATORIO DEGLI STUDI DI ONTOLOGIA DI TORINO estroverso.com Società Italiana di FILOSOFIA TEORETICA INTERNATIONAL CHAIR OF PHILOSOPHY JACQUES DERRIDA / LAW AND CULTURE FOURTH EDITION. POST-TRUTH, NEW REALISM, DEMOCRACY October 23rd October 24th Morning session Morning session 9.20 - 10.00 Greetings 10.00 - 10.30 Sanja Bojanic (University of Rijeka) Gianmaria Ajani (Rector, University of Turin) What Mocumentaries Tell Us about Truth? Renato Grimaldi (Director of the Department of Philosophy 10.30 - 11.00 Sebastiano Maffettone (LUISS Guido Carli University) and Educational Sciences, University of Turin) Derrida and the Political Culture of Post-colonialism Pier Franco Quaglieni (Director of Centro Pannunzio, Turin) Tiziana Andina (Director of LabOnt, University of Turin) 11.00 - 11.30 Coffee break 10.00 - 10.20 Prize Award Ceremony 11.30 - 12.00 Elisabetta Galeotti (University of Eastern Piedmont) Maurizio Ferraris (President of LabOnt, University of Turin) Types of Political Deception 10.20 - 11.10 Lectio Magistralis by Günter Figal (University of Freiburg) On Freedom Afternoon session 11.10 - 11.30 Coffee break 14.30 - 15.00 Jacopo Domenicucci (École Normale Supérieure, Paris) The Far We(b)st. Making Sense of Trust in Digital Contexts 11.30 - 12.00 Angela Condello (University of Roma Tre, University of Turin) 15.00 - 15.30 Davide Pala (University of Turin) Post-truth and Socio-legal Studies Citizens, Post-truth and Justice 12.00 - 12.30 Maurizio Ferraris (President of LabOnt, University of Turin) Deconstructing Post-truth 15.30 - 16.00 Break Afternoon session 16.00 - 16.30 Sara Guindani (Fondation Maison des sciences de l’homme, Paris) Derrida and the Impossible Transparency - Aesthetics and Politics 15.00 - 15.30 Luca Illetterati (University of Padua) Post-truth and Authority. -

The Packaging Machinery Cluster in Bologna

Collective Goods in the Local Economy: The Packaging Machinery Cluster in Bologna Paper by Henry Farrell and Ann-Louise Lauridsen March 2001 The debate about the industrial districts of central and north-eastern Italy has evolved over the last 25 years. Initially, many saw them as evidence that small firms could prosper contrary to the arguments of the proponents of big industry. Debate focussed on whether small firm industrial districts had a genuine independent existence, or were the contingent result of large firms’ outsourcing strategies (Brusco 1990, Bagnasco 1977, Bagnasco 1978). This spurred discussion about the role of local and regional government and political parties – small firm success might need services from government, associations, or local networks (Brusco 1982, Trigilia 1986). The difficulties that many industrial districts experienced in the late 1980s and early 1990s, together with the greater flexibility of large firms, led to a second wave of research, which asked whether industrial districts had long term prospects (Harrison 1994, Trigilia 1992, Bellandi 1992, Cooke and Morgan 1994). The most recent literature examines the responses of industrial districts to these challenges; it is clear that many industrial districts have adapted successfully to changing market conditions, but only to the extent that they have changed their modes of internal organisation, and their relationship with the outside world (Amin 1998, Bellandi 1996, Dei Ottati 1996a, Dei Ottati 1996b, Burroni and Trigilia 2001). While these debates have generated important findings, much basic conceptual work remains unfinished. There is still no real consensus about what forces drive evolution in industrial districts and lead to their success or failure. -

International Students Applications Enrolling in Master’S Degree Programmes A.Y

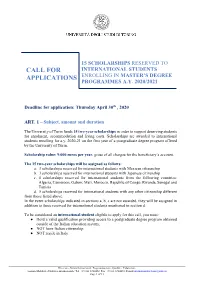

15 SCHOLARSHIPS RESERVED TO CALL FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS APPLICATIONS ENROLLING IN MASTER’S DEGREE PROGRAMMES A.Y. 2020/2021 Deadline for application: Thursday April 30th , 2020 ART. 1 – Subject, amount and duration The University of Turin funds 15 two-year scholarships in order to support deserving students for enrolment, accommodation and living costs. Scholarships are awarded to international students enrolling for a.y. 2020-21 on the first year of a postgraduate degree program offered by the University of Turin. Scholarship value: 9,000 euros per year, gross of all charges for the beneficiary’s account. The 15 two-year scholarships will be assigned as follows: a. 3 scholarships reserved for international students with Mexican citizenship b. 3 scholarships reserved for international students with Japanese citizenship c. 4 scholarships reserved for international students from the following countries: Algeria, Cameroon, Gabon; Mali, Morocco, Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Senegal and Tunisia d. 5 scholarships reserved for international students with any other citizenship different from those listed above. In the event scholarships indicated in sections a, b, c are not awarded, they will be assigned in addition to those reserved for international students mentioned in section d. To be considered an international student eligible to apply for this call, you must: ● Hold a valid qualification providing access to a postgraduate degree program obtained outside of the Italian education system; ● NOT have Italian citizenship; ● NOT reside in Italy. _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Direzione Attività Istituzionali, Programmazione, Qualità e Valutazione Sezione Mobilità e Didattica internazionale; Tel. +39 011 6704452; Fax +39 011 6704494; E-mail [email protected] Page 1 of 11 ART. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Welcome Message from the General Chair.......................................................... 2 M&N 2019 Organizers .......................................................................................... 3 Sponsors .............................................................................................................. 6 Patrons ................................................................................................................. 7 Exhibitors ............................................................................................................ 10 Monday, July 8 ....................................................................................................12 Tuesday, July 9 ................................................... ................................................19 Wednesday, July 10 ........................................................................................... 26 1 Welcome Message from the General Co-Chairs Dear colleagues and friends, On behalf of the entire Conference Committee, we are pleased to welcome you to the 5th IEEE International Symposium on Measurements and Networking (M&N 2019), which is held in Catania and hosted in Museo Diocesano in the heart of the city. The Symposium is mainly promoted by the IEEE IMS TC-37 Measurements and Networking, the IEEE IM Italy Chapter and by the IEEE Italy Section Systems Council Chapter. IEEE M&N is a privileged forum for the discussion of current and emerging trends on measurements, communications, computer science, -

ITINERARY: Milan, Bologna, Tuscany, Rome

ITINERARY: Milan, Bologna, Tuscany, Rome 13 May - 25 May 2018 UVU Culinary Arts Institute Day 1, May 13: USA / Milan, Italy Meals: D Arrival: Welcome to italy, one of the most famous travel destinations in the world! Prepare for an incredible journey as you experience everything Italy has to offer from the treasured cultural and historic sites to the world famous cuisine -arguably the most influential component of italian culture. From the aromatic white truffles of Montone to the rich seafood of the Cinque Terre coast, each province and region of Italy offers culinary treats for the most experienced of palates. Our journey will begin in Milan, one of the most prominent Italian cities located at the northernmost tip of Italy. Afternoon: The group will arrive at the Milan MXP (Milan Malpensa International Airport), where upon clearing customs and immigration your private driver and guide will greet the group and assist with the transfer to your hotel. Your group will be staying at the Kilma Hotel in Milan, a stylish modern 4-star hotel located 30 minutes from the airport. Upon arrival, the group will check-in to the hotel and prepare for the start of the experience. Evening: Once the entire group has arrived, we will have a delicious welcome dinner at a local favorite restaurant where we will sample some of the culinary flavors of Northern italy. After a delicious meal the group will retire for the evening. Kilma Hotel Milan Fiere Address: Via Privata Venezia Giulia, 8, 20157 Milano MI, Italy Phone: +39 02 455 0461 Day 2, May 14: Milan, Italy Meals: B, D Breakfast: Before setting out to explore the city of Milan, the group will have a delicious breakfast at the hotel where the group will be able to sample a variety of cheeses, charcuterie, and other traditional breakfast items. -

Print Special Issue Flyer

IMPACT CITESCORE FACTOR 2.4 2.847 SCOPUS an Open Access Journal by MDPI Anaerobic Digestion Processes Guest Editors: Message from the Guest Editors Dr. Pietro Bartocci This Special Issue on "Anaerobic Digestion Processes" aims CRB Italian Biomass Research to curate novel advances in biogas production and use, Centre, University of Perugia, focusing both on modeling and experimental campaigns. 06100 Perugia, Italy Topics include, but are not limited to, the following: [email protected] Modeling of anaerobic digestion and biogas Prof. Qing Yang John A. Paulson School of production; Engineering and Applied Organic substrate characterization and pre- Sciences, Harvard University, treatment; Cambridge, MA 02138, USA Biogas purification and biomethane production [email protected] and use; Biogas combustion in engines and turbines. Prof. Francesco Fantozzi Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Perugia, Via G. Duranti 67, 06125 Perugia, Italy [email protected] Deadline for manuscript submissions: 30 November 2021 mdpi.com/si/30853 SpeciaIslsue IMPACT CITESCORE FACTOR 2.4 2.847 SCOPUS an Open Access Journal by MDPI Editor-in-Chief Message from the Editor-in-Chief Prof. Dr. Giancarlo Cravotto Processes (ISSN 2227-9717) provides an advanced forum Department of Drug Science and for process/system-related research in chemistry, biology, Technology, University of Turin, material, energy, environment, food, pharmaceutical, Via P. Giuria 9, 10125 Turin, Italy manufacturing and allied engineering fields. The journal publishes regular research papers, communications, letters, short notes and reviews. Our aim is to encourage researchers to publish their experimental, theoretical and computational results in as much detail as necessary. There is no restriction on paper length or number of figures and tables. -

PERSONAL INFORMATION Daniele Ferrari, Piazza Di Pellicceria, N. 3/11

PERSONAL INFORMATION Daniele Ferrari, Piazza di Pellicceria, n. 3/11, 16121 Genova, [email protected] Sex Male - Date of birth 28/10/1984 – Nationality: Italian EDUCATION AND TRAINING 19 December 2014, PhD in Costitutional Law, University of Genoa, Faculty of Law, Supervisor: Professor Pasquale Costanzo, Subject: Costitutional Law – Ecclesiastical Law, Title: “La libertà di coscienza multilivello” 22 October 2008, Master Degree in Law, Vote: 110/110 with honors, University of Pisa, Faculty of Law, Supervisor: Professor R. Tarchi, Subject: Comparative Legal Systems - Ecclesiastical Law, Title: “Il principio di laicità e la libertà di manifestazione religiosa: itinerari di giurisprudenza nel contesto europeo” CURRENT POSITIONS Since 2017- Researcher in ecclesiastical and canon law, Department of Law, University of Siena, Italy Since 2017- Teaching assistant, Introduction to gender studies, Department of Law, University of Genoa, Italy Since 2016- Trainer, Ministry of Interior, Prefecture of Genoa Since 2016- Trainer, ARCI Association, Project “P.In. Pienamente Inclusivi” – Prog. 320 Fondo Asilo, Migrazione e Integrazione (FAMI) 2014-2020, Italy Since 2016- Post-doc researcher, Groupe Sociétés, Religions, Laïcités (GSRL), CNRS-EPHE, Paris Since 2016-Trainer Program “Immigrazione: ingresso e condizione degli stranieri in Italia”, Prefecture of Genoa, Italy Since 2016, Lawyer, Refugee Service, Association P.A. Croce Bianca Genovese, Genova, Italy Since 2015- Teaching Assistant, Public Law, Department of Political Science, University of Genoa, Italy Since 2012- Trainer, Order of Genoa lawyers, Italy Since 2011- Lawyer, Order of Genoa lawyers, Italy PREVIOUS POSITIONS 01.01.2010-19.12.2015- PhD Student, “Studi costituzionalistici italiani, europei e transnazionali”, XXV ciclo, University of Genoa, Department of Jurisprudence. -

67Th Economic Policy Panel

67th Economic Policy Panel Hosted by the Swiss National Bank Venue: Great Guild Hall, 2nd Floor, Zunfthaus zur Zimmerleuten Limmatquai 40, 8001 Zurich, Switzerland 12-13 April 2018 Programme Each session is 70 minutes in duration Author: 25 mins | Discussant: 15 mins (each) | Panel discussion: 15 mins * indicates presenting author Thursday 12 April 14:00 Registration and coffee on arrival 14:30 – 14:45 Opening Remarks Mr Thomas Moser, Alternate Member of the Governing Board, Swiss National Bank 14:45 – 15:55 Can Education Compensate the Effect of Population Aging on Macroeconomic Performance? Evidence from Panel Data Rainer Kotschy (LMU Munich) * Uwe Sunde (LMU Munich) Discussants: Francesco Drago (University of Messina) Pietro Biroli (University of Zurich) 15:55 – 17:05 Monetary Policy and Bank Profitability in a Low Interest Rate Environment * Carlo Altavilla (European Central Bank) Miguel Boucinha (European Central Bank) José-Luis Peydró (ICREA-UPF, CREI & BGSE) Discussants: Ralph De Haas (EBRD) Vasso Ioannidou (University of Lancaster) 17:05 – 17:20 coffee break 17:20 – 18:30 The Walking Dead?: Zombie Firms and Productivity Performance in OECD Countries Müge Adalet McGowan (OECD) Dan Andrews (OECD) * Valentine Millot (OECD) Discussants: Martin Brown (University of St.Gallen) Elena Carletti (Bocconi University) 20:00 Conference dinner at The Ballroom of the Savoy Hotel Baur en Ville Address: Poststrasse 12, 8001 Zurich Welcome address by Ms Andréa M. Maechler, Member of the Governing Board, Swiss National Bank Friday 13 April 08:30 – 09:40 Where Do People Get Their News? * Patrick Kennedy (Columbia University) Andrea Prat (Columbia University) Discussants: Roberto Galbiati (Sciences Po) David Hémous (University of Zurich) 09:40 – 10:50 Populism and Civil Society * Tito Boeri (Bocconi University) Prachi Mishra (IMF) Chris Papageorgiou (IMF) Antonio Spilimbergo (IMF) Discussants: Christina Gathmann (Heidelberg University) 10:50 – 11:10 Coffee break 11:10 – 12:20 The Gains from Economic Integration David Comerford (University of Strathclyde) * José V. -

Monday, 4Th November 2019 Cohort Updates Progress in ACC Research

PROGRAM 2019 ANNUAL MEETING OF ACC – ILCEC: ONCOLOGY RESEACH & APPLICATION OF BIOBANK Vinmec International Clinic, Hanoi 4th – 6th November 2019 Time Topic Presenter Monday, 4th November 2019 8:00 – 10:00 ACC Executive Committee (closed meeting) ACC Executive Committee members 9:30-10:00 Registration Opening Prof. Paolo Boffetta 10:00 – 10:30 Welcome; Opening remarks Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, USA Manami Inoue, Eiko Saito, Sarah K. Abe, 10:30 – 11:00 Update of the ACC Coordinating Center Rashedul Islam National Cancer Center, Japan Cohort Updates Dr. Arash Etemadi 11:00 – 11:15 Persian Cohort National Cancer Institute, NIH Dr. Yi-Ling Lin 11:15 – 11:30 Taiwan Biobank update Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Academia Sinica, Taiwan Dr. Xifeng Wu 11:30 – 11:45 Taiwan cohort Prof. Rui Lin 11:45 – 12:00 Guangxi Cohort Guangxi Medical University, China 12:00 – 13:30 Lunch (Visit to Vinmec Hospital) Prof. Keun-Young Yoo 13:30-14:00 Plenary lecture Seoul National University College of Medicine, Korea Progress in ACC research (15 min each) Acute effect of ambient air pollution on health in PhD. Nguyen Thi Trang Nhung 14:00 – 14:15 Northern Vietnam Hanoi University of Public Health, Vietnam PM concentration mapping from satellite images PhD. Nguyen Thi Nhat Thanh 14:15 – 14:30 for health impact assessment in Vietnam Vietnam National University Dr. George Downward Long-term ambient air pollution and mortality in 14:30 – 14:45 Institute for Risk Assessment Sciences, Utrecht the ACC, project update University, Netherlands Household Air Pollution Consortium (HAPCO) A/Prof. Dean Hosgood 14:45 – 15:00 updates Albert Einstein College of Medicine, USA 15:00 – 15:30 Coffee break (Poster session) Lifetime Overweight and Obesity: Impact on Dr.