Aesthetic Investigations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 20, 2017 Movie Year STAR 351 P Acu Lan E, Bish Op a B Erd

Movie Year STAR 351 Pacu Lane, Bishop Aberdeen Aberdeen Restaurant, Olancha Airflite Diner, Alabama Hills Ranch Anchor Alpenhof Lodge, Mammoth Lakes Benton Crossing Big Pine Bishop Bishop Reservation Paiute Buttermilk Country Carson & Colorado Railroad Gordo Cerro Chalk Bluffs Inyo Convict Lake Coso Junction Cottonwood Canyon Lake Crowley Crystal Crag Darwin Deep Springs Big Pine College, Devil's Postpile Diaz Lake, Lone Pine Eastern Sierra Fish Springs High Sierras High Sierra Mountains Highway 136 Keeler Highway 395 & Gill Station Rd Hoppy Cabin Horseshoe Meadows Rd Hot Creek Independence Inyo County Inyo National Forest June Lake June Mountain Keeler Station Keeler Kennedy Meadows Lake Crowley Lake Mary 2012 Gold Rush Expedition Race 2013 DOCUMENTARY 2013 Gold Rush Expedition Race 2014 DOCUMENTARY 2014 Gold Rush Expedition Race 2015 DOCUMENTARY 26 Men: Incident at Yuma 1957 Tristram Coffin x 3 Bad Men 1926 George O'Brien x 3 Godfathers 1948 John Wayne x x 5 Races, 5 Continents (SHORT) 2011 Kilian Jornet Abandoned: California Water Supply 2016 Rick McCrank x x Above Suspicion 1943 Joan Crawford x Across the Plains 1939 Jack Randall x Adventures in Wild California 2000 Susan Campbell x Adventures of Captain Marvel 1941 Tom Tyler x Adventures of Champion, The 1955-1956 Champion (the horse) Adventures of Champion, The: Andrew and the Deadly Double1956 Champion the Horse x Adventures of Champion, The: Crossroad Trail 1955 Champion the Horse x Adventures of Hajji Baba, The 1954 John Derek x Adventures of Marco Polo, The 1938 Gary Cooper x Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok 1951-1958 Guy Madison Affairs with Bears (SHORT) 2002 Steve Searles Air Mail 1932 Pat O'Brien x Alias Smith and Jones 1971-1973 Ben Murphy x Alien Planet (TV Movie) 2005 Wayne D. -

Stirling Silliphant Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2f59n87r No online items Finding Aid for the Stirling Silliphant Papers, ca. 1950-ca. 1985 PASC.0134 Finding aid prepared by Processed by UCLA Library Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by D.MacGill UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] Online finding aid last updated 14 August 2017 Finding Aid for the Stirling PASC.0134 1 Silliphant Papers, ca. 1950-ca. 1985 PASC.0134 Title: Stirling Silliphant papers Identifier/Call Number: PASC.0134 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 27.0 linear feet65 boxes. Date (inclusive): ca. 1950-ca. 1985 Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Stirling Silliphant Papers (Collection Number PASC 134). -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Ludacris – Red Light District Brothers in Arms the Pacifier

Pickwick's Video/DVD Rentals – New Arrivals 19. Sept. 2005 Marc Aurel Str. 10-12, 1010 Vienna Tel. 01-533 0182 – open daily – http://www.pickwicks.at/ __________________________________________________________________ Ludacris – Red Light District Genre: Music Synopsis: Live concert from Amsterdam plus three music videos. Brothers In Arms Genre: Action Actors: David Carradine, Kenya Moore, Gabriel Casseus, Antwon Tanner, Raymond Cruz Director: Jean-Claude La Marre Synopsis: A crew of outlaws set out to rob the town boss who murdered one of their kinsmen. Driscoll is warned so his thugs surround the outlaws and soon there is a shootout. Set in the American West. The Pacifier Genre: Comedy Actors: Vin Diesel, Lauren Graham, Faith Ford, Brittany Snow, Max Theriot, Carol Kane, Brad Gardett Director: Adam Shankman Synopsis: The story of an undercover agent who, after failing to protect an important government scientist, learns the man's family is in danger. In an effort to redeem himself, he agrees to take care of the man's children only to discover that child care is his toughest mission yet. Pickwick's Video/DVD Rentals – New Arrivals 19. Sept. 2005 Marc Aurel Str. 10-12, 1010 Vienna Tel. 01-533 0182 – open daily – http://www.pickwicks.at/ __________________________________________________________________ The Killer Language: Japanese Genre: Action Actors: Chow Yun Fat Director: John Woo Synopsis: The story of an assassin, Jeffrey Chow (aka Mickey Mouse) who takes one last job so he can retire and care for his girlfriend Jenny. When his employers betray him, he reluctantly joins forces with Inspector Lee (aka Dumbo), the cop who is pursuing him. -

Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pg3z8fg Author Chien, Irene Y. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Kristen Whissel Professor Greg Niemeyer Professor Abigail De Kosnik Spring 2015 Abstract Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair Programmed Moves examines the intertwined history and transnational circulation of two major videogame genres, martial arts fighting games and rhythm dancing games. Fighting and dancing games both emerge from Asia, and they both foreground the body. They strip down bodily movement into elemental actions like stepping, kicking, leaping, and tapping, and make these the form and content of the game. I argue that fighting and dancing games point to a key dynamic in videogame play: the programming of the body into the algorithmic logic of the game, a logic that increasingly organizes the informatic structure of everyday work and leisure in a globally interconnected information economy. -

Sam Urdank, Resume JULY

SAM URDANK Photographer 310- 877- 8319 www.samurdank.com BAD WORDS DIRECTOR: Jason Bateman CAST: Jason Bateman, Kathryn Hahn, Rohan Chand, Philip Baker Hall INDEPENDENT FILM Allison Janney, Ben Falcone, Steve Witting COFFEE TOWN DIRECTOR: Brad Campbell INDEPENDENT FILM CAST: Glenn Howerton, Steve Little, Ben Schwartz, Josh Groban Adrianne Palicki TAKEN 2 DIRECTOR: Olivier Megato TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX (L.A. 1st Unit) CAST: Liam Neeson, Maggie Grace,,Famke Janssen, THE APPARITION DIRECTOR: Todd Lincoln WARNER BRO. PICTURES (L.A. 1st Unit) CAST: Ashley Greene, Sebastian Stan, Tom Felton SYMPATHY FOR DELICIOUS DIRECTOR: Mark Ruffalo CORNER STORE ENTERTAINMENT CAST: Christopher Thornton, Mark Ruffalo, Juliette Lewis, Laura Linney, Orlando Bloom, Noah Emmerich, James Karen, John Caroll Lynch EXTRACT DIRECTOR: Mike Judge MIRAMAX FILMS CAST: Jason Bateman, Mila Kunis, Kristen Wiig, Ben Affleck, JK Simmons, Clifton Curtis THE INVENTION OF LYING DIRECTOR: Ricky Gervais & Matt Robinson WARNER BROS. PICTURES CAST: Ricky Gervais, Jennifer Garner, Rob Lowe, Lewis C.K., Tina Fey, Jeffrey Tambor Jonah Hill, Jason Batemann, Philip Seymore Hoffman, Edward Norton ROLE MODELS DIRECTOR: David Wain UNIVERSAL PICTURES CAST: Seann William Scott, Paul Rudd, Jane Lynch, Christopher Mintz-Plasse Bobb’e J. Thompson, Elizabeth Banks WITLESS PROTECTION DIRECTOR: Charles Robert Carner LIONSGATE CAST: Larry the Cable Guy, Ivana Milicevic, Yaphet Kotto, Peter Stomare, Jenny McCarthy, Joe Montegna, Eric Roberts DAYS OF WRATH DIRECTOR: Celia Fox FOXY FILMS/INDEPENDENT -

Actors' Stories Are a SAG Awards® Tradition

Actors' Stories are a SAG Awards® Tradition When the first Screen Actors Guild Awards® were presented on March 8, 1995, the ceremony opened with a speech by Angela Lansbury introducing the concept behind the SAG Awards and the Actor® statuette. During her remarks she shared a little of her own history as a performer: "I've been Elizabeth Taylor's sister, Spencer Tracy's mistress, Elvis' mother and a singing teapot." She ended by telling the audience of SAG Awards nominees and presenters, "Tonight is dedicated to the art and craft of acting by the people who should know about it: actors. And remember, you're one too!" Over the Years This glimpse into an actor’s life was so well received that it began a tradition of introducing each Screen Actors Guild Awards telecast with a distinguished actor relating a brief anecdote and sharing thoughts about what the art and craft mean on a personal level. For the first eight years of the SAG Awards, just one actor performed that customary opening. For the 9th Annual SAG Awards, however, producer Gloria Fujita O'Brien suggested a twist. She observed it would be more representative of the acting profession as a whole if several actors, drawn from all ages and backgrounds, told shorter versions of their individual journeys. To add more fun and to emphasize the universal truths of being an actor, the producers decided to keep the identities of those storytellers secret until they popped up on camera. An August Lineage Ever since then, the SAG Awards have begun with several of these short tales, typically signing off with his or her name and the evocative line, "I Am an Actor™." So far, audiences have been delighted by 107 of these unique yet quintessential Actors' Stories. -

Recommended Reading

RECOMMENDED READING The following books are highly recommended as supplements to this manual. They have been selected on the basis of content, and the ability to convey some of the color and drama of the Chinese martial arts heritage. THE ART OF WAR by Sun Tzu, translated by Thomas Cleary. A classical manual of Chinese military strategy, expounding principles that are often as applicable to individual martial artists as they are to armies. You may also enjoy Thomas Cleary's "Mastering The Art Of War," a companion volume featuring the works of Zhuge Liang, a brilliant strategist of the Three Kingdoms Period (see above). CHINA. 9th Edition. Lonely Planet Publications. Comprehensive guide. ISBN 1740596870 CHINA, A CULTURAL HISTORY by Arthur Cotterell. A highly readable history of China, in a single volume. THE CHINA STUDY by T. Colin Campbell,PhD. The most comprehensive study of nutrition ever conducted. ISBN 1-932100-38-5 CHINESE BOXING: MASTERS AND METHODS by Robert W. Smith. A collection of colorful anecdotes about Chinese martial artists in Taiwan. Kodansha International Ltd., Publisher. ISBN 0-87011-212-0 CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS TRAINING MANUALS (A Historical Survey) by Brian Kennedy and Elizabeth Guo CHRONICLES OF TAO, THE SECRET LIFE OF A TAOIST MASTER by Deng Ming-Dao. Harper San Francisco, Publisher ISBN 0-06-250219-0 (Note: This is an abridged version of a three- volume set: THE WANDERING TAOIST (Book I), SEVEN BAMBOO TABLETS OF THE CLOUDY SATCHEL (Book II), and GATEWAY TO A VAST WORLD (Book III)) CLASSICAL PA KUA CHANG FIGHTING SYSTEMS AND WEAPONS by Jerry Alan Johnson and Joseph Crandall. -

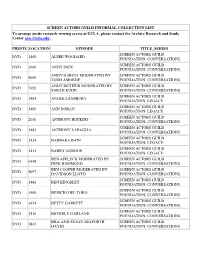

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST to Arrange Onsite Research Viewing Access at UCLA, Please Contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected]

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST To arrange onsite research viewing access at UCLA, please contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected] . PREFIX LOCATION EPISODE TITLE_SERIES SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1460 ALFRE WOODARD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1669 ANDY DICK FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY GARCIA MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8699 TODD AMORDE FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY RICHTER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7020 SARAH KUHN FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1484 ANGLE LANSBURY FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1409 ANN DORAN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 2010 ANTHONY HOPKINS FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1483 ANTHONY LAPAGLIA FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1434 BARBARA BAIN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1413 BARRY GORDON FOUNDATION: LEGACY BEN AFFLECK MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 6348 PETE HAMMOND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BEN COOPER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8697 DAVIDSON LLOYD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1486 BEN KINGSLEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1500 BENICIO DEL TORO FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1674 BETTY GARRETT FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1416 BEVERLY GARLAND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL AND SUSAN SEAFORTH SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1843 HAYES FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL PAXTON MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7019 JENELLE RILEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS -

Emmy Nominations

69th Emmy Awards Nominations Announcements July 13, 2017 (A complete list of nominations, supplemental facts and figures may be found at Emmys.com) Emmy Noms to date Previous Wins to Category Nominee Program Network 69th Emmy Noms Total (across all date (across all categories) categories) LEAD ACTRESS IN A DRAMA SERIES Viola Davis How To Get Away With Murder ABC 1 3 1 Claire Foy The Crown Netflix 1 1 NA Elisabeth Moss The Handmaid's Tale Hulu 1 8 0 Keri Russell The Americans FX Networks 1 2 0 Evan Rachel Wood Westworld HBO 1 2 0 Robin Wright House Of Cards Netflix 1 6 0 LEAD ACTOR IN A DRAMA SERIES Sterling K. Brown This Is Us NBC 1 2 1 Anthony Hopkins Westworld HBO 1 5 2 Bob Odenkirk Better Call Saul AMC 1 11 2 Matthew Rhys The Americans FX Networks 2* 3 0 Liev Schreiber Ray Donovan Showtime 3* 6 0 Kevin Spacey House Of Cards Netflix 1 11 0 Milo Ventimiglia This Is Us NBC 1 1 NA * NOTE: Matthew Rhys is also nominated for Guest Actor In A Comedy Series for Girls * NOTE: Liev Schreiber also nominamted twice as Narrator for Muhammad Ali: Only One and Uconn: The March To Madness LEAD ACTRESS IN A LIMITED SERIES OR A MOVIE Carrie Coon Fargo FX Networks 1 1 NA Felicity Huffman American Crime ABC 1 5 1 Nicole Kidman Big Little Lies HBO 1 2 0 Jessica Lange FEUD: Bette And Joan FX Networks 1 8 3 Susan Sarandon FEUD: Bette And Joan FX Networks 1 5 0 Reese Witherspoon Big Little Lies HBO 1 1 NA LEAD ACTOR IN A LIMITED SERIES OR A MOVIE Riz Ahmed The Night Of HBO 2* 2 NA Benedict Cumberbatch Sherlock: The Lying Detective (Masterpiece) PBS 1 5 1 -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................