Baptist Connections and Heritage at Wake Forest University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlantic Coast Conference

ATLANTIC COAST CONFERENCE OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER 2011 Atlantic Coast Conference Early Season Football Television Schedule Release (All times Eastern) Date ............. Game ...................................................... .................. Network ................................ Gametime Sept. 1 ........... Western Carolina at Georgia Tech ... ..................... ESPN3.com ................................. 7:30 pm Sept. 3 ........... Northwestern at Boston College ....... ..................... ESPNU .......................................... Noon Sept. 3 ........... Appalachian State at Virginia Tech .. ..................... ACC Network ............................... 12:30 pm Sept. 3 ........... Troy at Clemson ........................................ ..................... ESPN3.com ................................... 3:30 pm Sept. 3 ........... Louisiana Monroe at Florida State ... ..................... ESPNU ........................................... 3:30 pm Sept. 3 ........... James Madison at North Carolina ..... ..................... RSN ..... ........................................... 3:30 pm Sept. 3 ........... Liberty at NC State ................................... ..................... ESPN3.com ................................. 6 pm Sept. 3 ........... William & Mary at Virginia .................. ..................... ESPN3.com ................................. 6 pm Sept. 3 ........... Richmond at Duke ................................... ..................... ESPN3.com ................................. 7 pm -

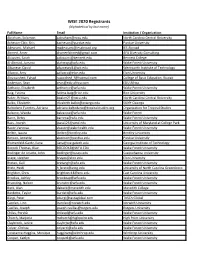

WISE 2020 Registrants

WISE 2020 Registrants (alphabetical by last name) Full Name Email Institution / Organization Abraham, Solomon [email protected] North Carolina Central University Acheson-Clair, Kris [email protected] Purdue University Adewumi, Michael [email protected] IES Abroad Ahmed, Amer [email protected] AFA Diversity Consulting Akiwumi, Sarah [email protected] Bennett College Al-Ahmad, Jumana [email protected] Wake Forest University Albanese, David [email protected] Wentworth Institute of Technology Allocco, Amy [email protected] Elon University Alruwaished, Fahad [email protected] College of Basic Education, Kuwait Anderson, Sean [email protected] EDU Africa Anthony, Elizabeth [email protected] Wake Forest University Baig, Fatima [email protected] Rice University Baker, Brittany [email protected] North Carolina Central University Balko, Elizabeth [email protected] SUNY-Oswego Baltodano Fuentes, Adriana [email protected] Organization for Tropical Studies Balzano, Wanda [email protected] Wake Forest Barre, Betsy [email protected] Wake Forest University Bass, Joseph [email protected] University of Maryland at College Park Baute,Vanessa [email protected] Wake Forest University Beltre, Isaura [email protected] Bentley University Benson, Annette [email protected] Purdue University Blumenfeld-Gantz, Ilana [email protected] Georgia Institute of Technology Bocook Thomas, Blair [email protected] Wake Forest University Bodinger de Uriarte, John [email protected] Susquehanna University braye, stephen -

Civil Rights Activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, 1960-1963

SUTTELL, BRIAN WILLIAM, Ph.D. Campus to Counter: Civil Rights Activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, 1960-1963. (2017) Directed by Dr. Charles C. Bolton. 296 pp. This work investigates civil rights activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, in the early 1960s, especially among students at Shaw University, Saint Augustine’s College (Saint Augustine’s University today), and North Carolina College at Durham (North Carolina Central University today). Their significance in challenging traditional practices in regard to race relations has been underrepresented in the historiography of the civil rights movement. Students from these three historically black schools played a crucial role in bringing about the end of segregation in public accommodations and the reduction of discriminatory hiring practices. While student activists often proceeded from campus to the lunch counters to participate in sit-in demonstrations, their actions also represented a counter to businesspersons and politicians who sought to preserve a segregationist view of Tar Heel hospitality. The research presented in this dissertation demonstrates the ways in which ideas of academic freedom gave additional ideological force to the civil rights movement and helped garner support from students and faculty from the “Research Triangle” schools comprised of North Carolina State College (North Carolina State University today), Duke University, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Many students from both the “Protest Triangle” (my term for the activists at the three historically black schools) and “Research Triangle” schools viewed efforts by local and state politicians to thwart student participation in sit-ins and other forms of protest as a restriction of their academic freedom. -

Wake Forest University Fact Book 2013-2014 Twenty-Third Edition

2013‐2014 Fact Book Office of Institutional Research Wake Forest University Fact Book 2013-2014 Twenty-third Edition – April 2014 Reynolda Campus Wake Forest College, School of Business, School of Law, Graduate School, and Divinity School Bowman Gray Campus Wake Forest University School of Medicine (includes Physician Assistant Program) and Graduate School Office of Institutional Research Phil Handwerk, Director Adam Shick, Associate Director Sara Gravitt, Assistant Director Justin DeBenedetto, Graduate Assistant P. O. Box 7373 Reynolda Station, Winston-Salem, NC 27109 (336) 758-5244 Web site: http://www.wfu.edu/ir Table of Contents General Information History....................................................................................................................................1 Mission Statement ..................................................................................................................1 Statement of Principle on Diversity .......................................................................................2 Chronological History ............................................................................................................2 Accreditation ..........................................................................................................................3 Board of Trustees ...................................................................................................................4 Administration (Executive Council) ......................................................................................4 -

Curriculum Vitae Wayne Denton

Curriculum Vitae Wayne Denton March 27, 2015 General Information University address: Family and Child Sciences College of Human Sciences Sandels Building 0240 Florida State University Tallahassee, Florida 32306-1491 Phone: (850) 644-1412; Fax: (850) 644-3439 E-mail address: [email protected] Professional Preparation 1990 Ph.D., Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN. Major: Child Development and Family Studies. Marriage and Family Therapy. 1982 M.D., University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, Chicago, IL. Major: Medicine. 1978 B.A., Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN. Major: Psychology. With highest distinction. Nondegree Education and Training 1982–1986 Residency in Psychiatry, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC. Professional Credential(s) 2011–present Licensed Medical Doctor, Florida, ME 108940. 2005–present Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist, Texas, 5162. 1995–present Approved Supervisor, American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy. 1993–present Board Certified in Psychiatry, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Vita for Wayne Denton 1983–present Diplomate, National Board of Medical Examiners. Professional Experience 2010–present Professor of Marriage and Family Therapy, Family and Child Sciences, Florida State University. 2004–2010 Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Psychiatry, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. 1998–2004 Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Psychiatry, Wake Forest University School of Medicine. 1990–1998 Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Wake Forest University School of Medicine. 1986–1990 Psychiatrist, Wabash Valley Hospital. Visiting Professorship(s) 2006 Psychotherapist in Residence, Pastoral Counseling & Education Center, Dallas, TX. Honors, Awards, and Prizes Family Studies Center nominated for Outstanding Teaching Site Award, Psychiatry Residents Organization, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas (2009). -

2008-2009 Academic Catalog

ACADEMIC CATALOG 2008-2009 www.peace.edu A Liberal Arts & Sciences College for Women Raleigh, NC ACADEMIC CATALOG 2008–2009 Peace College does not discriminate in its admission of women students, regardless of race, creed, color, religion, age, national origin, sexual orientation, disability, or veteran status. In our employment practices, Peace College seeks to hire, promote, and retain the best qualified individuals, regardless of race, creed, color, religion, age, sex, national origin, sexual orientation, disability, or veteran status. This is done in accordance with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title IX of the Educational Amendments of 1972, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Americans with Disabilities Act. The college complies with the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act of 1974, as amended, regarding information on file and students’ access to their records. Directory information (name, address, class, and major) may be released, unless the student requests in writing that her information be withheld. Peace College is accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia, 30033-4097, telephone 404-679-4501) to award baccalaureate degrees. 2 LIST OF DEPARTMENTS Inquiries should be directed as indicated below. Call the campus receptionist at 919-508-2000 and ask to be connected to the appropriate individual: Academic Advising, Assistant Dean for Advising and Retention Academic Matters, Dean of Academic Affairs Academic Support Programs, -

Senator Smith. Referred To

GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 2007 S D SENATE JOINT RESOLUTION DRSJR55173-LG-297 (02/28) Sponsors: Senator Smith. Referred to: 1 A JOINT RESOLUTION HONORING THE WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY 2 FOOTBALL TEAM ON WINNING THE 2006 ATLANTIC COAST 3 CONFERENCE CHAMPIONSHIP. 4 Whereas, on December 2, 2006, Wake Forest University's football team won 5 the 2006 Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) championship, defeating Georgia Tech by a 6 score of 9-6 in Jacksonville, Florida; and 7 Whereas, this victory earned Wake Forest a berth in the Bowl Championship 8 Series and a bid to the 2007 FedEx Orange Bowl; and 9 Whereas, Wake Forest was the first team from North Carolina to earn a berth 10 in one of the top five bowls (Orange, Fiesta, Rose, Sugar, and Cotton) since 1961; and 11 Whereas, this championship gave Wake Forest its second ACC title, having 12 won its first title in 1970; and 13 Whereas, Wake Forest finished the 2006 football season with an 11-3 record, 14 shattering the previous school record of eight wins captured in 1944, 1979, and 1992; 15 and 16 Whereas, Wake Forest's five wins in September 2006 marked the most 17 victories in any month of the year in Demon Deacon football history; and 18 Whereas, Wake Forest won six ACC games for the first time in school history 19 and won the ACC's Atlantic Division after being picked to finish last by the league's 20 media in the preseason; and 21 Whereas, Wake Forest was the most improved team in America, based upon 22 win differential; and 23 Whereas, Wake Forest was the first team in ACC history -

Wake Forest University Department of Engineering a Welcome from the Chair

WAKE DWNTWN / W-S WFU WAKE 1834 / 1956 2017 WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF ENGINEERING A WELCOME FROM THE CHAIR Welcome to Wake Forest’s Department of Engineering! We are delighted by your interest in our innovative and collaborative program, and we hope you find this booklet informative as you explore how we are reimagining undergraduate engineering education. At Wake Forest Engineering, our mission is to educate the whole engineer. The world today is a complex place, and the needs of society are ever-changing. We need a new generation of engineers to deliver sustainable solutions to humanity’s most pressing challenges. Through collaborative project-based work and real-world applications, we are committed to producing fearless problem solvers who are prepared to tackle these challenges. Our engineers will bring their broad perspectives, entrepreneurial mindsets, unyielding agility and virtuous characters to the task. We invite you to learn more about who we are and join us on our unique journey to educating the next generation of engineers. Sincerely, Olga Pierrakos, Ph.D. Founding Chair and Professor Department of Engineering 2 // WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY WHY A B.S. ENGINEERING DEGREE? This is the number one question we get — as well as the one we are most excited to answer. Wake Forest is pioneering a new path for engineering education, with the nation’s only B.S. program offered by an undergraduate-only department with a curriculum grounded in the liberal arts tradition at a research university. Our students strive for the best -

Operation Exporting Freedom: the Quest for Democratization Via United States Military Operations

Operation Exporting Freedom: The Quest for Democratization via United States Military Operations by John A. Tures The wave of the future is not the conquest of the world by a single dogmatic creed, but the liberation of the diverse energies of free nations and free men. —President John F. Kennedy, University of California at Berkeley Address, March 23, 1962 INTRODUCTION1 Since September 11, 2001, the United States has launched military operations against Afghanistan and Iraq. The names of these operations, Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom, imply that at least part of the mission will be devoted to promoting democracy in these countries. Proponents of exporting freedom extol the virtues of such policies, pointing to success stories in Germany and Japan after World War II, as well as more recent cases, such as Panama after 1989. Critics assail America’s track record of using military force to promote democratization, citing failures in Somalia and Haiti, as well as incomplete efforts such as Bosnia. The question before us is whether Afghanistan and Iraq will look more like the former group, or begin to resemble the latter group. The answer is critical for the future of American foreign policy. Other “Axis of Evil” states are awaiting confrontation with the United States. People in Central Asia, the Middle East, East Asia, and Africa could find themselves along the battle lines in the “War on Terrorism.” Furthermore, Americans, who are being asked to sacrifice the things they hold dear, are anxious about the outcome. If the United States can effectively promote democratization, others might support the spread of freedom. -

Buildings and Grounds 1

Buildings and Grounds 1 Computer Science in Manchester Hall and the Departments of Politics BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS and International Affairs, Economics and Sociology in Kirby Hall. The Reynolda Campus of Wake Forest, which opened in the summer of Farrell Hall, named for Wake Forest parents and benefactors Michael (LLD 1956 upon the institution's move from its original home near Raleigh, ’13, P ’10) and Mary (P ’10) Farrell, broke ground in April 2011 and is home is situated on approximately 340 acres. Its physical facilities consist to the School of Business. It hosted its first classes in July 2013 and was of more than 80 buildings, most of which are of modified Georgian formally dedicated in November 2013. architecture and constructed of Old Virginia brick trimmed in granite and William B. Greene Jr. Hall, named for alumnus and benefactor Bill Greene limestone. ('59), houses the Departments of Psychology, German and Russian, and The main Quadrangle, Hearn Plaza, is named for Wake Forest’s 12th Romance Languages. president, Thomas K. Hearn Jr., who served from 1983 to 2005. James R. Scales Fine Arts Center, named for James Ralph Scales, Wake Manchester Plaza, named for benefactors and Wake Forest parents Doug Forest's 11th president, supports the functions of studio art, theatre, Manchester (P ’03, P ’06) and Elizabeth Manchester (P ’03, P ’06), is musical and dance performances and instruction in art history, drama located on south campus. The Reynolda Gardens complex, consisting and music. Off its main lobby is the Charlotte and Philip Hanes Gallery, of about 128 acres and including Reynolda Woods, Reynolda Village, a facility for special exhibitions. -

Wake Forest Magazine Explores the Future

WAKE FOREST’S NEW FRONTIER AT INNOVATION QUARTER / FATE OF THE AMAZON / FUTURE CITIZENS FALL 2016 THE MAGAZINE OF WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY 20 WAKE FOREST’S FEATURES NEW FRONTIER By Carol L. Hanner Photography by Ken Bennett At Innovation Quarter, the University is staking a claim in downtown Winston-Salem and expanding education beyond the bubble. 2 54 BREAKTHROUGHS THE FATE OF THE AMAZON By Kerry M. King (’85) By Kerry M. King (’85) From physics to philosophy, faculty A new research center in Peru aims to reduce gold- say the past informs the future for mining-related environmental degradation. their fields. 12 62 THE MAKING OF TIME CAPSULE FUTURE CITIZENS By Cherin C. Poovey (P ’08) By Maria Henson (’82) Books, photos, high-top Chucks, a Cook-Out cup There’s good news about politics: and a tambourine. Don’t open until 2116. Democracy Fellows remain engaged participants in the process. 70 18 GLOBAL MICROEXPERIENCES THE FUTURE OF By Dean Franco HIGHER EDUCATION At Mother, so dear, new students, curriculum and models Four questions for President Nathan for study abroad. One English professor describes his O. Hatch. class’ journey to Venice, a crossroads of Jewish culture. 10 0 46 CONSTANT & TRUE WORLD’S FAIR WITH By Jim O’Connell (’13) A WAKE FOREST FLAIR My mother’s name is Kathy, and my father’s name is By Kerry M. King (’85) Reproductive Sample No. 119. The students’ challenge? Plan the 2025 World’s Fair. DEPARTMENTS 76 | Around the Quad 79 | Remember When? 78 | Philanthropy 80 | Class Notes WAKEFOREST FROM theh PRESIDENT MAGAZINE with this edition, Wake Forest Magazine explores the future. -

Wake Forest Vs Clemson (10/11/1975)

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1975 Wake Forest vs Clemson (10/11/1975) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "Wake Forest vs Clemson (10/11/1975)" (1975). Football Programs. 117. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/117 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ideally situated to save you time and money. When Eastern meets your distribution needs, you have an experienced group working for you in two ideal locations: Greenville, South Carolina, and Jacksonville, Florida. The recent addition of two brand new distribution centers in Imeson Park at Jacksonville gives us total floor space of 1 ,167,000 sq. ft., with more projected. Our materials handling and warehouse maintenance equipment is the finest. Our personnel hand picked. Our responsiveness to your instructions quick enough to move goods on a same-day basis.