Romantic Topics in Elgar's Cello Concerto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOSVC Weblist 8: Erato Box 51

DOSVC Weblist 8: Erato Box 51 Label Serial No Composer, Work or Title Artists Record Condition notes Erato EPR 15554 Honegger Symphonie, Roussel Suite Munch, L'ORTF, Lamoreux Near Mint cutout notch UR Erato NUM 75106 Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique Conlon, Orch Nat de France Near Mint Gatefold album Erato NUM 75126 Schumann: Cello Concerto/Four Horns Lodeon/Devoyon/Guschlbauer Factory Sealed Cut Out notch Erato NUM 75146 Mahler/Strauss: Quartets for strings & piano Quatuor Ivaldi Near Mint Cut Out notch Erato NUM 75166 Corelli: Christmas Concerto Scimone, Solisti Veneti Factory Sealed Gatefold album Erato NUM 75167 Mozart: Sonata in D Major/C Minor/Fantasy Pires Factory Sealed Erato NUM 75168 Chopin Sonata 2 and 3 Duchable Factory Sealed Gatefold album, CO notch Erato NUM 75169 Handel: Alcina Gardiner, English Baroque Factory Sealed Gatefold album, CO notch 2 copies Erato NUM 75170 Offenbach/Cherubini/Saint-Saens/Godard Horne/Foster Factory Sealed Gatefold album, CO notch Erato NUM 75171 vocal by: Tosti/Rotoli/Brogi/Denza Raimondi/Scimone Factory Sealed Gatefold album, CO notch Erato NUM 75174 Delalande: Simphonies pour les Soupers du Roy Paillard Chamb Orch Factory Sealed Gatefold album, CO notch Erato NUM 75177 Liszt: Sonata in B Minor/Two Legends Duchable Factory Sealed Erato NUM 75178 Schumann: Scenes from Childhood/Forest Pires Factory Sealed Gatefold album, CO notch Erato NUM 75180 Mozart: Symphonies 38 & 39 Conlon , Scottish Chamber Near Mint Cut Out notch Erato NUM 75181 Motets of Vivaldi Scimone, Solisti Veneti Near Mint Cut Out -

Early 20Th Century Classical

Early 20th Century Classical Contents A few highlights 1 Background stories 1 Early 20th Century Classical – Title order 2 Early 20th Century Classical – Composer order 9 Early 20th Century Classical – Pianist order 17 The 200 MIDI files in this category include works by 20th Century composers such as Debussy, Fauré, Granados, Milhaud, Korngold, Rachmaninoff, Ravel and Respighi. Some of the works are from the late 19th century, giving a snapshot of music from the Romantics, through Impressionists to modern day compositions. Pianists include Alexander Brailowsky, Ottorino Respighi, Claude Debussy; Ernő Dohnányi, Walter Gieseking, Percy Grainger, Enrique Granados, Leo Ornstein, Sergei Prokofiev, Sergei Rachmaninoff and Maurice Ravel. The composers in this list are usually playing their own works. A few highlights Afternoon of a Faun (Prelude to) by Debussy played by Richard Singer (two rolls joined) Allegro De Concierto (Concert Allegro) by Granados, played by Granados’ pupil Paquita Madriguera Enigma Variations (complete) by Elgar, played by duo pianists Cuthbert Whitmore & Dorothy Manley Flirtation in a Chinese Garden; Rush Hour in Hong Kong by Abram Chasins, played by the composer Fountains of Rome by Respighi, played by the composer and Alfredo Casella Malagueña, by Ernesto Lecuona, played by the composer Naila Ballet Waltz, by Delibes, arranged by Dohnányi, played by Mieczyslaw Munz Pictures at an Exhibition (incomplete) by Moussgorsky played by Sergei Prokofiev Rhapsodies Op.11 (1 to 4), by Dohnányi, all but one (No.3) played by the composer Spanish Dances (Danza Espanolas) by Granados, played by the composer Turkey Op.18, No.3 (In The Garden Of The Old Harem) by Blanchet, played by Ervin Nyiregyházi Waltzes Noble and Sentimental, by Ravel played by the composer. -

Elgar, Cello Concerto in E Minor

Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85 i. Adagio; Moderato ii. Lento; Allegro molto iii. Adagio iv. Allegro; Moderato; Allegro, ma non troppo; Poco più lento; Adagio Edward Elgar enjoys a curious reputation in his own country. To many, he is the composer of overtly nationalistic music such as Pomp and Circumstance, the musical incarnation of Edwardian imperialism. Although early works such as the Enigma Variations and Imperial March garnered him praise and fame, it is his later works from 1918-1919 that are much more autobiographical in content – none more so than the Cello Concerto in E minor. The Concerto was mostly composed between 1918 and 1919 at Brinkwells, a cottage in the Sussex woods where he wrote three other chamber works – the Violin Sonata, String Quartet and Piano Quintet. Like these other Brinkwells compositions, the Cello Concerto is a deeply introspective work which reveals much about the composer’s state of mind: an aging artist concerned about his waning popularity, his wife’s failing health, and reflecting on the horrors of the First World War. Despite a grossly under-rehearsed première at the Queen’s Hall on 27 October 1919, it has since been established as perhaps the finest cello concerto in the repertoire, alongside Dvořák’s, and the only work of Elgar’s to enjoy regular performances outside the English-speaking world. The Cello Concerto is an emotionally draining work not only for the players but also the listener, its overwhelming mood one of melancholy and autumnal world-weariness. The first movement opens with a declamatory, grandiose statement by the soloist leading, in almost improvisatory style, into a lilting melody; there is a wistfully lyrical middle section before the opening melody returns. -

≥ Elgar Sea Pictures Polonia Pomp and Circumstance Marches 1–5 Sir Mark Elder Alice Coote Sir Edward Elgar (1857–1934) Sea Pictures, Op.37 1

≥ ELGAR SEA PICTURES POLONIA POMP AND CIRCUMSTANCE MARCHES 1–5 SIR MARK ELDER ALICE COOTE SIR EDWARD ELGAR (1857–1934) SEA PICTURES, OP.37 1. Sea Slumber-Song (Roden Noel) .......................................................... 5.15 2. In Haven (C. Alice Elgar) ........................................................................... 1.42 3. Sabbath Morning at Sea (Mrs Browning) ........................................ 5.47 4. Where Corals Lie (Dr Richard Garnett) ............................................. 3.57 5. The Swimmer (Adam Lindsay Gordon) .............................................5.52 ALICE COOTE MEZZO SOPRANO 6. POLONIA, OP.76 ......................................................................................13.16 POMP AND CIRCUMSTANCE MARCHES, OP.39 7. No.1 in D major .............................................................................................. 6.14 8. No.2 in A minor .............................................................................................. 5.14 9. No.3 in C minor ..............................................................................................5.49 10. No.4 in G major ..............................................................................................4.52 11. No.5 in C major .............................................................................................. 6.15 TOTAL TIMING .....................................................................................................64.58 ≥ MUSIC DIRECTOR SIR MARK ELDER CBE LEADER LYN FLETCHER WWW.HALLE.CO.UK -

Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello

Saturday Evening, January 25, 2020, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello SAMUEL BARBER (1910–81) Toccata Festiva (1960) DANIEL FICARRI, Organ DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–75) Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 (1966) Largo Allegretto Allegretto DANIEL HASS, Cello Intermission CHRISTOPHER ROUSE (1949–2019) Processional (2014) JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833–97) Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73 (1877) Allegro non troppo Adagio non troppo Allegretto grazioso Allegro con spirito Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 50 minutes, including an intermission This performance is made possible with support from the Celia Ascher Fund for Juilliard. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Juilliard About the Program the organ’s and the orchestra’s full ranges. A fluid approach to rhythm and meter By Jay Goodwin provides momentum and bite, and intricate passagework—including a dazzling cadenza Toccata Festiva for the pedals that sets the organist’s feet SAMUEL BARBER to dancing—calls to mind the great organ Born: March 9, 1910, in West Chester, music of the Baroque era. Pennsylvania Died: January 23, 1981, in New York City Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH In terms of scale, pipe organs are Born: September 25, 1906, in Saint Petersburg different from every other type of Died: August 9, 1975, in Moscow musical instrument, and designing and assembling a new one can be a challenge There are several reasons that of architecture and engineering as complex Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. -

Themenkatalog »Musik Verfolgter Und Exilierter Komponisten«

THEMENKATALOG »Musik verfolgter und exilierter Komponisten« 1. Alphabetisches Verzeichnis Babin, Victor Capriccio (1949) 12’30 3.3.3.3–4.3.3.1–timp–harp–strings 1908–1972 for orchestra Concerto No.2 (1956) 24’ 2(II=picc).2.2.2(II=dbn)–4.2.3.1–timp.perc(3)–strings for two pianos and orchestra Blech, Leo Das war ich 50’ 2S,A,T,Bar; 2(II=picc).2.corA.2.2–4.2.0.1–timp.perc–harp–strings 1871–1958 (That Was Me) (1902) Rural idyll in one act Libretto by Richard Batka after Johann Hutt (G) Strauß, Johann – Liebeswalzer 3’ 2(picc).1.2(bcl).1–3.2.0.0–timp.perc–harp–strings Blech, Leo / for coloratura soprano and orchestra Sandberg, Herbert Bloch, Ernest Concerto Symphonique (1947–48) 38’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc(3):cyms/tam-t/BD/SD 1880–1959 for piano and orchestra –cel–strings String Quartet No.2 (1945) 35’ Suite Symphonique (1944) 20’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc:cyms/BD–strings Violin Concerto (1937–38) 35’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc(2):cyms/tgl/BD/SD– harp–cel–strings Braunfels, Walter 3 Chinesische Gesänge op.19 (1914) 16’ 3(III=picc).2(II=corA).3.2–4.2.3.1–timp.perc–harp–cel–strings; 1882–1954 for high voice and orchestra reduced orchestraion by Axel Langmann: 1(=picc).1(=corA).1.1– Text: from Hans Bethge’s »Chinese Flute« (G) 2.1.1.0–timp.perc(1)–cel(=harmonium)–strings(2.2.2.2.1) 3 Goethe-Lieder op.29 (1916/17) 10’ for voice and piano Text: (G) 2 Lieder nach Hans Carossa op.44 (1932) 4’ for voice and piano Text: (G) Cello Concerto op.49 (c1933) 25’ 2.2(II=corA).2.2–4.2.0.0–timp–strings -

String Quartet in E Minor, Op 83

String Quartet in E minor, op 83 A quartet in three movements for two violins, viola and cello: 1 - Allegro moderato; 2 - Piacevole (poco andante); 3 - Allegro molto. Approximate Length: 30 minutes First Performance: Date: 21 May 1919 Venue: Wigmore Hall, London Performed by: Albert Sammons, W H Reed - violins; Raymond Jeremy - viola; Felix Salmond - cello Dedicated to: The Brodsky Quartet Elgar composed two part-quartets in 1878 and a complete one in 1887 but these were set aside and/or destroyed. Years later, the violinist Adolf Brodsky had been urging Elgar to compose a string quartet since 1900 when, as leader of the Hallé Orchestra, he performed several of Elgar's works. Consequently, Elgar first set about composing a String Quartet in 1907 after enjoying a concert in Malvern by the Brodsky Quartet. However, he put it aside when he embarked with determination on his long-delayed First Symphony. It appears that the composer subsequently used themes intended for this earlier quartet in other works, including the symphony. When he eventually returned to the genre, it was to compose an entirely fresh work. It was after enjoying an evening of chamber music in London with Billy Reed’s quartet, just before entering hospital for a tonsillitis operation, that Elgar decided on writing the quartet, and he began it whilst convalescing, completing the first movement by the end of March 1918. He composed that first movement at his home, Severn House, in Hampstead, depressed by the war news and debilitated from his operation. By May, he could move to the peaceful surroundings of Brinkwells, the country cottage that Lady Elgar had found for them in the depth of the Sussex countryside. -

Czech Portraits Friday, Mar

Czech Portraits Friday, Mar. 4 10:30am Vítězslav NovákNovák, Czech composer (1870-1949) Vítězslav Novák held an almost “cult status” popu- larity among his native Czech people. Like his mentor Antonín Dvořák, he used thematic mate- rial from Czech folk melodies in his music and was inspired by the landscape of his native country in South Bohemia. In 1908 he succeeded Dvořák as professor of composition at the Prague Conserva- tory and helped lead the next generation of Czech composers into the new age. Lady Godiva Overture Composed in 1907, duration is 15 minutes This piece was commissioned to open a Czech play of the same name and is taken from a 13th century story about the noble-hearted and beautiful Lady REPERTOIRE Godiva. It tells the story of the Lady’s efforts to end the suffering and oppression of the people in Coventry under her husband’s rule, Count Leofric. After multiple pleas to ask the Count to lower the • NOVÁK taxes, Leofric finally offers her a deal. Lady Godiva Overture The terms, which she ultimately ac- cepts, require her to ride through • ELGAR town naked in exchange for an end to Concerto in E Minor for the heavy taxation. The piece portrays Cello and Orchestra the characters, Count Leofric and • NOVÁK Lady Godiva through contrasting Eternal Longing Op. 33 melodies. Count Leofric has a very fierce motif in C minor while Lady • SMETANA Godiva is delicately portrayed in Eb Moldau from Má Vlast major. The music moves back in forth Coventry painted by Herbert Edward Cox, United Kingdom between the two as if in argument. -

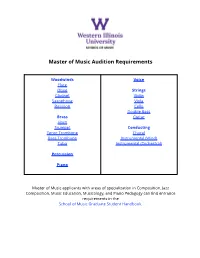

Audition Requirements

Master of Music Audition Requirements Woodwinds Voice Flute Oboe Strings Clarinet Violin Saxophone Viola Bassoon Cello Double Bass Brass Guitar Horn Trumpet Conducting Tenor Trombone Choral Bass Trombone Instrumental (Wind) Tuba Instrumental (Orchestral) Percussion Piano Master of Music applicants with areas of specialization in Composition, Jazz Composition, Music Education, Musicology, and Piano Pedagogy can find entrance requirements in the School of Music Graduate Student Handbook. Flute Faculty: Dr. Suyeon Ko; Email: [email protected] • Mozart: Concerto in G Major or D Major, K. 313 or K. 314 (Movements I and II) • A 19th- or 20th-century French work from Flute Music by French Composers or equivalent • An unaccompanied 20th- or 21st-century work • Five orchestral excerpts from Baxtresser, Orchestral Excerpts for Flute, or equivalent • Sight reading Oboe Faculty: Emily Hart; Email: [email protected] • Choose two from the following: ◦ Saint-Saëns or Poulenc sonata (Movement I) ◦ Mozart or Haydn concerto (Movement III) ◦ Any Telemann or Vivaldi concerto or sonata (Movements I and II) ◦ Britten Six Metamorphoses (any three movements) • Choose two of the following orchestral excerpts (all excerpts may be found in the Rothwell books, Difficult Passages, published by Boosey and Hawkes): ◦ Brahms: Violin Concerto (slow movement excerpt) ◦ Rossini: La Scala di Seta (slow and fast excerpts) ◦ Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) ◦ Prokofiev: Symphony No. 1 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) • Sight reading Clarinet Faculty: Eric Ginsberg; Email: [email protected] • Choose two movements from one of the following: ◦ Mozart: Concerto in A Major, K. 622 ◦ Weber: Concerto No. 1 in F Minor, Op. -

Cellist Zuill Bailey with Helen Kim and the KSU Symphony Orchestra

SCHOOL of MUSIC where PASSION is Zuill Bailey,heard Cello featuring Helen Kim, Violin Robert Henry, Piano KSU Symphony Orchestra Nathaniel F. Parker, Music Director and Conductor Wednesday, October 9, 2019 | 8:00 PM Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall musicKSU.com 1 heard Program LUKAS FOSS (1922-2009) CAPRICCIO MAX BRUCH (1838-1920) KOL NIDREI, OPUS 47 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893) VARIATIONS ON A ROCOCO THEME, OPUS 33 Zuill Bailey, Cello Robert Henry, Piano –INTERMISSION– JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) CONCERTO FOR VIOLIN, CELLO, AND ORCHESTRA IN A MINOR, OPUS 102 I. ALLEGRO II. ANDANTE III. VIVACE NON TROPPO Zuill Bailey, Cello Helen Kim, Violin Kennesaw State University Symphony Orchestra Nathaniel F. Parker, Conductor We welcome all guests with special needs and offer the following services: easy access, companion seating locations, accessible restrooms, and assisted listening devices. Please contact a patron services representative at 470-578-6650 to request services. 2 Kennesaw State University School of Music KSU Symphony Orchestra Personnel Nathaniel F. Parker, Music Director & Conductor Personnel listed alphabetically to emphasize the importance of each part. Rotational seating is used in all woodwind, brass, and percussion sections. Flute Violin Cello Don Cofrancesco Melissa Ake^, Garrett Clay Lorin Green concertmaster Laci Divine Jayna Burton Colin Gregoire^, principal Oboe Abigail Carpenter Jair Griffin Emily Gunby Robert Cox^ Joseph Grunkmeyer, Robert Simon Mary Catherine Davis associate principal -

Franz Anton Hoffmeister’S Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra in D Major a Scholarly Performance Edition

FRANZ ANTON HOFFMEISTER’S CONCERTO FOR VIOLONCELLO AND ORCHESTRA IN D MAJOR A SCHOLARLY PERFORMANCE EDITION by Sonja Kraus Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2019 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Emilio Colón, Research Director and Chair ______________________________________ Kristina Muxfeldt ______________________________________ Peter Stumpf ______________________________________ Mimi Zweig September 3, 2019 ii Copyright © 2019 Sonja Kraus iii Acknowledgements Completing this work would not have been possible without the continuous and dedicated support of many people. First and foremost, I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to my teacher and mentor Prof. Emilio Colón for his relentless support and his knowledgeable advice throughout my doctoral degree and the creation of this edition of the Hoffmeister Cello Concerto. The way he lives his life as a compassionate human being and dedicated musician inspired me to search for a topic that I am truly passionate about and led me to a life filled with purpose. I thank my other committee members Prof. Mimi Zweig and Prof. Peter Stumpf for their time and commitment throughout my studies. I could not have wished for a more positive and encouraging committee. I also thank Dr. Kristina Muxfeldt for being my music history advisor with an open ear for my questions and helpful comments throughout my time at Indiana University. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Tertis's Viola Version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to Clevelandclassical

Preview Heights Chamber Orchestra conductor's notes: Tertis's viola version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to ClevelandClassical An old adage suggested that violists were merely vio- linists-in-decline. That was before Lionel Tertis! He was born in 1876 of musical parents who had come to England from Poland and Russia and, at three years old, he started playing the piano. At six he performed in public, but had to be locked in a room to make him practice, a procedure that has actually fostered many an international virtuoso. At thirteen, with the agree- ment of his parents, he left home to earn his living in music playing in pickup groups at summer resorts, accompanying a violinist, and acting as music attendant at a lunatic asylum. +41:J:-:/1?<1>95@@1041?@A0510-@(>5:5@E;88131;2!A?5/@-75:3B5;85:-?45? "second study," but concentrating on the piano and playing concertos with the school or- chestra. As sometime happens, his violin teacher showed little interest in a second study <A<58-:01B1:@;8045?2-@41>@4-@41C-?.1@@1>J@@102;>@413>;/1>E@>-01 +5@4?A/4 encouragement, Tertis decided he had to teach himself. Fate intervened when fellow stu- dents wanted to form a string quartet. Tertis volunteered to play viola, borrowed an in- strument, loved the rich quality of its lowest string and thereafter turned the old adage up- side down: a not very obviously gifted violinist becoming a world class violist. But, until the viola attained respectability in Tertis’s hands, composers were reluctant to write for the instrument.