3 Anthropology and Disaster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental Assessment and Management Framework (EAMF)

Environmental Assessment & Management Framework - SCDP 33333333Environmental Assessment and Public Disclosure Authorized Management Framework Strategic Cities Development Project (SCDP) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development January 2016 January, 2016 Page 1 Environmental Assessment & Management Framework - SCDP Table of Contents CHAPTER 1: PROJECT DESCRIPTION ...........................................................................1 1.1 Project concept & objective ....................................................................................... 1 1.2 Project Description ..................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Objective of the Environmental Assessment and Management Framework (EAMF) ........................................................................................................................ 2 CHAPTER 2: POLICY, LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK .............4 2.1 Overview of Environmental Legislation ................................................................ 4 2.2 Detail Review of Key Environmental and Urban Services Related Legislation 5 2.3 World Bank Safeguard Policies .............................................................................. 16 2.4 World Heritage Convention ................................................................................... 21 CHAPTER 3: DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT AREA ............................................22 -

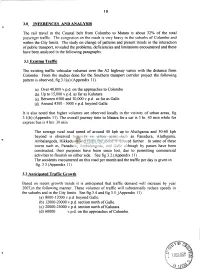

10 3.0. INFERENCES and ANALYSIS the Rail Travel in the Coastal Belt

10 3.0. INFERENCES AND ANALYSIS The rail travel in the Coastal belt from Colombo to Matara is about 32% of the total passenger traffic. The congestion on the roads is very heavy in the suburbs of Colombo and within the City limits. The study on change of patterns and present trends in the interaction of public transport, revealed the problems, deficiencies and limitations encountered and these have been analysed in the following paragraphs. 3.1 Existing Traffic The existing traffic vehicular volumes over the A2 highway varies with the distance from Colombo. From the studies done for the Southern transport corridor project the following pattern is observed, fig.3.1(a) (Appendix 11). (a) Over 40,000 v.p.d. on the approaches to Colombo (bi Up to 15,000 v.p.d. as far as Kalutara {cL Between 6500 and 10,000 v.p.d. as far as Galle. (di Around 4500 - 5000 v.p.d. beyond Galle. It is also noted that higher volumes are observed locally in the vicinity of urban areas, fig 3.1(b) (Appendix 11). The overall journey time to Matara for a car is 3 hr. 45 min while for express bus is 4 hrs. 30 min. The average rural road speed of around 40 kph up to Aluthgama and 50-60 kph beyond is observed however in urban areas such as Panadura, Aluthgama, Ambalangoda, Hikkaduwa and Galle the speed is reduced further. In some of these towns such as, Panadura, Ambalangoda, and Galle although by passes have been constructed, their purposes have been since lost, due to permitting commercial activities to flourish on either side. -

World Bank Document

Draft Environmental Assessment & Management Framework - SCDP Final Environmental Public Disclosure Authorized Management & Assessment Framework Strategic Cities Development Project (SCDP) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Ministry of Defense and Urban Development January 2014 January, 2014 Page 1 Draft Environmental Assessment & Management Framework - SCDP Table of Contents Chapter 1 – Project Description 1.1 Project Concept and objective . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 1.2 Project Description .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 Chapter 2 – Policy, Legal and Administrative Framework 2.1 Overview of Environmental Legislation.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 4 2.2. Detail Review of Key Environmental and Urban Services Related Legislation. .. .. 4 2.3 World Bank Safeguard Policies.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 11 Chapter 3 – Description of the Project Area 3.1 Kandy.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 16 3.1.1 Urban Morphology.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 18 3.1.2 Physical Environment.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 18 3.1.2.1 Topography.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 18 3.1.2.2 Climate.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 18 3.1.2.3 Main Water bodies and flow regimes.. .. .. .. .. .. 18 3.1.3Ecologically Important/Sensitive Habitats.. .. .. .. .. .. .. 20 3.1.3.1 UdawatteKelle Sanctuary.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 20 3.1.3.2 Dulumadalawa Forest Reserve and the Hantana Range.. .. .. .. 22 3.1.3.3 Kandy Lake and Surrounding Catchment.. .. .. .. .. .. 22 3.1.4 Built Environment.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 23 3.1.5 Historical and Cultural -

Sri Lanka Rupee (Rs) Rs1.00 = $0.009113278 $1.00 = Rs109.730000

Resettlement Plan May 2011 Document Stage: Draft SRI: Additional Financing for National Highway Sector Project Katurukunda–Neboda Highway (B207) Prepared by Road Development Authority for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 11 May 2011) Currency unit – Sri Lanka rupee (Rs) Rs1.00 = $0.009113278 $1.00 = Rs109.730000 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank CEA – Central Environmental Authority CSC – Chief Engineer’s Office CSC – Construction Supervision Consultant CV – Chief Valuer DSD – Divisional Secretariat Division DS – Divisional Secretary ESD – Environment and Social Division GN – Grama Niladhari GND – Grama Niladhari Division GOSL – Government of Sri Lanka GRC – Grievance Redress Committee IOL – inventory of losses LAA – Land Acquisition Act LARC – Land Acquisition and Resettlement Committee LARD – Land Acquisition and Resettlement Division LAO – Land Acquisition Officer LARS – land acquisition and resettlement survey MOLLD – Ministry of Land and Land Development NEA – National Environmental Act NGO – nongovernmental organization NIRP – National Involuntary Resettlement Policy PD – project director PMU – project management unit RP – resettlement plan RDA – Road Development Authority ROW – right-of-way SD – Survey Department SES – socioeconomic survey SEW – Southern Expressway STDP – Southern Transport Development Project TOR – terms of reference WEIGHTS AND MEASURES Ha hectare km – kilometer sq. ft. – square feet sq. m – square meter NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Challenges in Implementing Best Practices in Involuntary Resettlement a Case Study in Sri Lanka

Challenges in Implementing Best ChALLengeS in impLementing BeSt pr Practices in Involuntary Resettlement A Case Study in Sri Lanka Infrastructure projects sometimes physically displace households and disrupt income sources and livelihoods. The Asian Development Bank offers several good governance practices to its borrowers to minimize such adverse impacts, especially since the absorption of such best practices by countries is usually slow and erratic. This book presents an in-depth case study from a complex and sensitive infrastructure project in Sri Lanka, where international best practices in involuntary resettlement were successfully merged with local legal systems. The book demonstrates that the application of best practices to infrastructure projects needs continuous consultations with affected people and a firm commitment of resources. AC About the Asian Development Bank tiCeS in i ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, nvo it remains home to a large share of the world’s poor. ADB is committed ChAllenges In ImPlementIng Best to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally LuntA sustainable growth, and regional integration. PRACtICes In InvoluntARy Resettlement Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the ry A Case Study in Sri Lanka region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries reSettLement -

FEASIBILITY of a ONE-WAY TRAFFIC SYSTEM for COLOMBO CITY IMP ART •Pwrhsiu Q| MORATUWA.Smuuw| MORATUWA * U

LB/DON/lft/:<l FEASIBILITY OF A ONE-WAY TRAFFIC SYSTEM FOR COLOMBO CITY IMP ART _ •PWrHSIU Q| MORATUWA.SmUuW| MORATUWA * U. L. Tissa This thesis was submitted to the Department of Civil Engineering University of Moratuwa in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering. o^v Supervised by \ Professor Amal S. Kumarage Department of Civil Engineering University of Moratuwa Sri Lanka UN I'ne5l5 March 2004 80146 I Diversity of Moratuwa S0146 DECLARATION The work included in this thesis is part or whole, has not been submitted for any other academic qualification at any institution. U.L.Tissa Prof. Amal S. Kumarage ABSTRACT Traffic management in main cities has become an absolute need due to the increase in the number of vehicles in the limited road space, at present. There are numerous limitations that restrict the widening of roads to cater to the demand of the ever-increasing vehicular load in an already congested city such as Colombo. The question is how are we going to differentiate between the benefit and the cost of development. It is very important to look for cost effective methods by minimizing the adverse effects on the economy in a developing country like Sri Lanka. The objective of this research was to check the suitability of a One-way traffic system in a selected area of the Colombo City. The most congested areas, which could be expanded later, depending on the results obtained, have been selected first. The study area was confined to Northern and Southern banks of Beira Lake in Colombo Fort area. -

Proposed Supplementary Loan and Technical Assistance Grant Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka: Southern Transport Development Project

Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors Project Number: 26522 February 2008 Proposed Supplementary Loan and Technical Assistance Grant Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka: Southern Transport Development Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 13 February 2008) Currency Unit – Sri Lanka rupee/s (SLRe/SLRs) SLRe1.00 = $0.0093 $1.00 = SLRs108.05 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank CEA – Central Environment Authority CRP – Compliance Review Panel CSC – construction supervision consultant EIA – environmental impact assessment EIRR – economic internal rate of return EMP – environment management plan ESD – Environment and Social Division GDP – gross domestic product ICB – international competitive bidding IRP – income restoration program JBIC – Japan Bank for International Cooperation km – kilometer LAR – land acquisition and resettlement LARC – land acquisition and resettlement committee LIBOR – London interbank offered rate MOHRD – Ministry of Highways and Road Development NDF – Nordic Development Fund OCR – ordinary capital resources PMU – project management unit RDA – Road Development Authority RIP – resettlement implementation plan ROW – right of way SDR – special drawing rights SL – supplementary loan Sida – Swedish International Development Cooperation TA – technical assistance UDA – Urban Development Authority VOC – vehicle operating cost NOTES (i) The fiscal year of the Government and its agencies ends on 31 December. (ii) In this report, “$” refers to US dollars Vice President L. Jin, Operations Group 1 Director General K. Senga, South Asia Department (SARD) Director K. Higuchi, Transport and Communications Division, SARD Team leader D. N. Utami, Senior Environment Specialist, SARD Team members M. Alam, Senior Infrastructure Specialist, SARD N. M. Amerasinghe, Project Implementation Officer (Agriculture and Environment), SARD A. Gamaathige, Social Sector/Resettlement Officer, SARD R. -

ADB Accountability Mechanism Compliance Review Panel On

ADB Accountability Mechanism Compliance Review Panel Final Report to the Board of Directors on CRP Request No. 2004/1 on the Southern Transport Development Project in Sri Lanka (ADB Loan No. 1711-SRI[SF]) 22 June 2005 Contents Page About the Compliance Review Panel.......................................................................................iii Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................iv Abbreviations, Glossary and Currency ....................................................................................v Map.............................................................................................................................................vii Executive Summary.................................................................................................................viii I. Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 II. Description of the Project ...................................................................................................3 A. Scope ....................................................................................................................3 B. Agencies and Financing ........................................................................................3 C. Status of Project ....................................................................................................4 III. Request for Compliance -

E®>©9© ©Ess© T3tia>©». @ <§»©)© CONTENTS

CL CONTENTS Page Acknowledgement 1 Abstract 2 Introduction 3 Methodology 7 Inferences & Analysis 10 Discussion 15 Recommendations 17 References e®>©9© ©ess© t3tia>©». @ <§»©)© jg Appencjixl 19 Appendix II 27 70816 LIST OF TABLES (Appendix I) Page Table 2.1 Rail passengers - coastline 20 Table 2.2 Passengers rail and bus 21 Table 2.3 Average trip length 22 Table 3.1 Regression analysis - passenger forecast 23 Table 3.2 Tally of passengers - rail (23.09.98) 24 Table 3.3 Tally of passengers - rail (25.09.98) 25 Table 3.6 Passenger distribution in carriages 26 Annexure 1 Origin - destination matrix (passengers) 1-12 (1991 -1996) Annexure 2 Origin - destination matrix (passenger km) 1-12 (1991 -1996) LIST OF FIGURES (Appendix II) Page Figure 1.1 Administrative divisions of Sri Lanka 28 Figure 3.1(a) Traffic flow 29 Figure 3.1 (b) Urban sections 3 0 Figure 3.2 Transport network in Sri Lanka 31 Figure 3.3 Vehicle volumes and accidents 32 Figure 3.4 Traffic growth 33 Figure 3.5 Speed - Flow Relationships 34 Figure 3.5(a) Urban hierarchy 35 Figure 3.6 Comparison of ixmning times on bus & train 36 Acknowledgement The author wishes to place on record, the appreciation for the invaluable guidance and encouragement given by Prof. Dayantha Wijeyesekera, Prof. L.L. Ratnayake of University of Moratuwa and Mr. D.S. Jayaweera of the Transport Studies Planning Centre , throughout this project, along with the swift and timely assistance rendered by Mr. U.E. Storm World Bank Consultant Srilanka Railway and Mr. Sunil Peiris Planning officer, National Transport Commission without which collecting the data would have been difficult. -

Govt Allocates Rs. 24 Million for Emergency Relief to Drought Hit

The Island Home News Page Three Friday 30th October, 2009 3 No air conditioning, no surgery, patients suffer Govt allocates Rs. 24 million for by Lalith Chaminda and S. K. Kaluarachchi Galle Corrs. emergency relief to drought hit districts Surgery at the Karapitiya Hospital in Galle came to an District were affected. tate 60 to 70 tanks in the district and com- Sammanthurai, Erangana, Lahugala, abrupt halt as a result of the by Franklin R. Satyapalan The badly affected Divisional mence a clean drinking water supply proj- Pottuvil, Tirukovil, Alyadivembu and hospital’s air conditioner being The Government will provide Rs. 24 Secretariat areas are Siyambalanduwa, ect to pump water from the Menik Ganga Addalachchenai were badly affected and out of order for the last three million to nine drought affected districts – Madulla, Buttala, Moneragala, in Nakkala in the Badalkumbura area. action was taken to provide water round weeks. Ampara, Batticaloa, Badulla, Matale, Tanamalwila, Sevenagala, Medagama and Sarath Perera also said that Rs 2.4 mil- the clock utilising 15 or more bowsers. Surgery to be performed on Moneragala, Polonnaruwa, Hambantota, Wellawaya. Initial action had been taken to lion had been allocated to the Ampara dis- Additional District Secretary of cancer patients and others suf- Kurunegala and Puttalam as a first step to utilise 20 bowsers to provide drinking trict, Rs. 595,000 to Matale , Rs. 16.6 million Ampara Asanka Abeywardena said water to these villagers. to Moneragala, Rs. 2.1 million to Batticaloa, fering from serious ailments provide emergency relief to 200,000 or more requests have been forwarded to provide Ratnasiri said that in coordination with Rs. -

Environmental Assessment Vocational Education Reconstruction

Sri Lanka Tsunami Reconstruction Program (SLTRP) USAID Contract # 386-C-00-05-00166-00 Environmental Assessment Vocational Education Reconstruction Component December 2006 SLTRPR-0040 In association with EML Consultants, Chemonics International Inc, DEVTECH, FNI, Engineering Consultants Ltd., Lanka Hydraulic Institute, MICD, and Uni-Consultancy Service SRI LANKA TSUNAMI RECONSTRUCTION PROGRAM ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR VOCATIONAL EDUCATION CENTER List of Abbreviations and Acronyms......................................................................................iii Executive Summary.................................................................................................................... iv CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................1 1.1 Overview ...............................................................................................................1 1.2 Site Selection Process ...........................................................................................3 1.3 Purpose of the Environmental Assessment Report .........................................6 1.4 Scope and Objectives of the EA report ..............................................................7 1.5 Definition of the Project Impact Area................................................................8 1.6 Use of Construction Materials ............................................................................8 1.7 Alternatives ...........................................................................................................9 -

Ministry of Power Brochure

Upcoming infrastructure project pipeline in Sri Lanka As per new Ministerial Allocations in the Gazette issued on 09 August 2020 Ministry of Power Extension of the Lakvijaya Coal Power Plant - additional 300MW - approx. USD 450 Mn The largest power station in Sri Lanka and the only coal plant in the country. Fully owned by the Govt. of Sri Lanka (GoSL) through Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB). 900 MW capacity was commissioned in 2011. The GoSL is currently in discussion with China Machinery Engineering Corporation (CMEC) to carryout this extension. CMEC was the Engineering Procurement and Construction (EPC) contractor that was responsible for development of the Lakvijaya Power Plant as well. The conversion of Kalanithissa Thermal Power Plant to a LNG Power Plant (Sojitz Kelanitissa/ former AES Kelanitissa) 163 MWcapacity - one of the initial Independent Power Purchase agreements (IPP) in Sri Lanka - 20 year. The Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) will expire in 2023 and expected to be operated as a CEB plant until 2033. Currently owned and operated by Sojitz Corporation, Japan. The plant is currently running on Diesel/Heavy Fuel (i.e. diesel-fired combined cycle power plant). It requires additional investment to convert to LNG Power Plant. Estimated at USD 921Mn - inclusive of the Land Based Terminal cost and the Floating Storage Regasification Unit (FSRU); as per CEB Long Term Generation Expansion Plan 2020 - 2039 Ministry of Power Expansion of Kerawalapitiya Power Plant Phase 01 - 300 MW capacity - comissioned in 2007/2010. Currently, it is an IPP till 2035 owned by West Coast Power Ltd (major shareholders include GoSL. EPF, LECO, Lakdhanavi Ltd/ LTL holdings plus other shareholders).